Headaches - tension

Highlights

What Are Tension-Type Headaches?

Tension-type headaches are the most common type of headache, accounting for about half of all headaches. The pain is usually mild-to-moderate in intensity, with a steady pressing or tightening quality (like a vise being squeezed around the head). The headache is not accompanied by nausea or vomiting, and the pain is not increased by routine physical activity such as walking or climbing stairs. A tension-type headache attack can last anywhere from 30 minutes to an entire week.

Who Gets Tension-Type Headaches?

Women are more likely to get tension-type headaches than men. Nearly everyone will have at least one tension-type headache at some point in their lives. Many people who have migraine headaches also have tension-type headaches.

What Is The Difference Between Tension-Type Headaches and Migraine Headaches?

Migraines and tension headaches have some similar characteristics, but also some important differences:

- Migraine pain is usually throbbing and while tension-type headache pain is usually a steady ache.

- Migraine pain often affects only one side of the head while tension-type headache pain typically affects both sides of the head.

- Migraine headaches, but not tension-type headaches, may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting, sensitivity to both light and sound, or aura.

Treatment

Treatment of tension-type headache focuses on relieving pain when attacks occur, and preventing recurrence of attacks. Most tension-type headache attacks respond to simple over-the-counter pain relievers such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic), or naproxen (Aleve, generic).

Patients who have two or more tension-type headache attacks each month should talk to their doctors about preventive therapy. This may include a tricyclic antidepressant, such as amitriptyline (Elavil, generic), combined with behavioral therapies. Behavioral treatment approaches include relaxation therapy, biofeedback, stress management, and cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Introduction

Most people have had headaches. There are many different kinds of headaches, and they range from being an infrequent annoyance to a persistent, severe, and disabling medical condition.

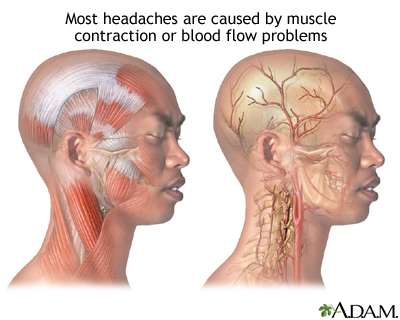

Brain tissue itself does not generate sensations of pain, so the brain is not what hurts when you have a headache. Rather, the pain occurs in some of the following locations:

- The tissues covering the brain

- The attaching structures at the base of the brain

- Muscles and blood vessels around the scalp, face, and neck

Doctors categorize headaches as either primary or secondary. The category helps to distinguish the many different kinds of headaches and to determine right treatments for each.

Primary and Secondary Headaches

A headache is considered primary when it is not caused by another medical condition or disease. Most primary headaches fall into three main types: tension-type, migraine, and cluster headaches.

- Tension-type headache is the most common primary headache and accounts for 90% of all headaches.

- Migraines are the second most common primary headaches. Migraine is referred to as a neurovascular headache because it is most likely caused by an interaction between blood vessel and nerve abnormalities.

- Cluster headache is a less common type of primary headache that is sometimes referred to as a neurovascular headache.

Secondary headaches are caused by other medical conditions, such as sinus infections, neck injuries, and strokes. About 2% of headaches are secondary to abnormalities or infections in the nasal or sinus passages, and they are commonly referred to as sinus headaches.

Chronic Daily Headaches

Chronic daily headaches are defined as any benign headache that occurs at least 15 days a month and is not associated with a serious neurologic abnormality. Most people with these headaches have them daily or almost daily and they can be quite debilitating.

Chronic daily headaches can begin as tension headaches, migraines, or a combination of these or other headache types. Chronic daily headaches are subdivided into two categories:

- Short-duration headaches, or those lasting fewer than 4 hours. The most common short-acting chronic headaches are cluster headaches.

- Long-duration headaches, which last more than 4 hours. Tension-type headaches are the most common type of long-duration chronic (recurring) headaches and, in fact, the most common type of chronic headaches in general.

Tension-Type Headaches

Tension-type headaches, also called muscle contraction headaches or simply tension headaches, are the most common of all headaches. They are classified into four types:

- Frequent episodic tension-type headache. Headaches occur at least once but not more than 15 days per month for at least 3 months (a minimum of 12 days but not more than 180 days per year). Headaches last from at least 30 minutes to 7 days.

- Infrequent episodic tension-type headache. At least 10 episodes of headache that occur less than 1 day per month (12 days per year). Because these headaches occur infrequently, they do not impact a patient's quality of life as severely as frequent episodic headaches and may not require attention from a medical professional.

- Chronic tension-type headache. Headaches occur at least 15 days per month for at least 3 months (45 days per year). The headache persists for hours at a time and may be continuous.

- Probable tension-type headache. Probable tension headaches may be classified as probable frequent episodic, probable infrequent episodic, or probable chronic. They have most, but not all, of the symptoms of tension-type headaches and are not attributed to migraine without aura or other neurological disorders. Probable chronic tension-type headache may be related to medication overuse.

Causes

Doctors are not sure what causes tension headaches. Although they once thought that tension-type headaches were primarily due to muscle contractions, this theory has largely been discounted. Instead, researchers think that tension-type headaches occur due to an interaction of several factors that involve pain sensitivity and perception, as well as the role of brain chemicals (neurotransmitters).

Genetic factors are likely be involved in chronic tension-type headache, whereas environmental factors (physical and psychological stress) may play a role in the physiologic processes involved with episodic tension-type headache.

Pain Sensitivity and Perception

Research indicates that patients with tension-type headache may have abnormalities in the central nervous system, which increase their sensitivity to pain. The central nervous system includes the nerves in the brain and spine.

Tension-type headaches may also be linked to myofascial trigger points in the neck and shoulder muscles. Myofascial pain involves the fascia (connective tissue) and muscles. Trigger points are knots in the muscle tissue that can cause tightness, weakness, and intense pain in various areas of the body. For example, a trigger point in the shoulder may result in headache.

Brain Chemicals (Neurotransmitters)

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers in the brain. Several types of neurotransmitters affect how the brain reacts to pain stimulation. In particular, serotonin (also called 5-HT) and nitric oxide are thought to be involved in these chemical changes. Release of these chemicals may activate nerve pathways in the brain, muscles, or elsewhere and increase pain.

Triggers for Tension-Type Headache

In addition to stress, many different factors can trigger or aggravate tension-type headaches.

Medication and Substance Overuse. About a third of persistent headaches -- whether chronic migraine or tension-type -- are medication-overuse headaches. These are the result of a rebound effect caused by the regular overuse of headache medications. Nearly any type of headache medication can produce this effect. Headaches can also occur after withdrawing from caffeine, nicotine, or alcohol.

Poor Posture and Work Conditions. Working or sleeping in an awkward position can contribute to posture problems (especially those that affect muscles in neck and shoulders) that trigger headaches. Eyestrain caused by overwork can also play a role.

Fatigue. Lack of sleep and tiredness from overwork are also headache triggers.

Foods and Beverages. Rapid consumption of ice cream or other very cold foods or beverages is the most common trigger of sudden headache pain, which may be prevented by warming the food or drink for a few seconds in the front of the mouth before swallowing. (However, ice cream headaches are not tension headaches.) Not eating on time is also a trigger for headache.

Physical Activity. Intense physical exertion (including athletics or sexual activity) as well as lack of physical activity can trigger headaches. However, tension-type headache pain is not worsened by routine physical activity.

Dental Problems. Jaw clenching or teeth grinding, especially during sleep, are signs of temporomandibular joint dysfunction (TMJ, also known as TMD). TMJ pain can occur in the ear, cheek, temples, neck, or shoulders. This condition often coexists with chronic tension headache. Some patients with TMJ may see improvement in tension-type headaches from procedures or exercise therapies that specifically address the dental condition.

Physical Trauma. Whiplash or head or neck injury can lead to headaches.

Hormonal Changes. Hormonal changes, such as those that occur during the menstrual cycle or perimenopause, can affect headache occurrence.

Causes of Secondary Headaches

About 90% of people seeking help for headaches have a primary headache. The rest are secondary headaches, caused by an underlying disorder that produces headache as a symptom. More than 300 conditions can cause headaches. These can range from sinus conditions to brain tumor. While fear of brain tumor is common among people with headaches, headache is almost never the first or only sign of a tumor. Changes in personality and mental functioning, vomiting, seizures, and other symptoms are more likely to appear first.

Risk Factors

Tension-type headaches are the most common type of headache. Nearly everyone has at least one tension-type headache during their lifetime. Episodic tension-type headaches are far more common than chronic tension-type headaches.

Headaches in Adults

Gender. Tension-type headaches are more common among women than men.

Age. Tension-type headaches are most likely to occur among people in their 40s. They tend to occur less as people become older.

Headaches in Children

Headaches are rare before age 4 but become more common throughout childhood, reaching a peak at around age 13. Children with tension-type headaches may also suffer from an emotional disorder.

Psychosocial factors associated with childhood tension-type headaches include:

- Sleep problems. Many children who experience chronic daily headaches suffer from sleep disturbances, especially difficulty falling asleep.

- Moderate or severe depression.

- Emotional problems including repressed anger.

- Family stress. This includes maternal illness or separation, family bereavement, relationship problems, mental illness in a family member, and other stressful family events.

- Problems at school. According to a National Headache Foundation survey, nearly 30% of children miss school because of headaches. For many children, the start of the school season can be a particularly stressful time.

The National Headache Foundation recommends these tips for parents:

- Keep a diary of your child's headaches noting time of onset, length and intensity of attack, location of pain, and dietary triggers.

- Make sure your child gets plenty of sleep at regular times.

- Avoid changes in child's eating routine (hunger and eating at irregular times can trigger headaches).

- Discuss any headache concerns with your child's doctor.

Prognosis

Both episodic tension-type headache and chronic daily headache affect quality of life. Tension-type headache episodes are rarely disabling, however, and rarely require emergency treatment. If they do, there is usually a migraine component occurring with the tension-type headache.

Nevertheless, although they are not medically dangerous, chronic tension headaches can have a negative impact on quality of life, families, and work productivity. Several studies have reported lower quality of life for people with any chronic daily headache compared to those with no headaches or only episodic ones. Many people with chronic tension-type headaches also suffer from anxiety and depression.

Tension-type headaches can, in most cases, be treated and prevented. Episodes of these headaches can also resolve over time. In one study, nearly half of patients with frequent or chronic tension-type headache were not experiencing headaches when examined 3 years later. Patients who have both tension-type and migraine headaches may face steeper challenges in recovery.

Symptoms

Tension-type headaches tend to have the following symptoms:

- The pain is commonly described as a tight feeling, as if the head were in a vise. It usually occurs on both sides of the head and is often experienced in the forehead, in the back of the head and neck, or in both regions. Soreness in the shoulders or neck is common.

- The pain is of mild-to-moderate intensity and is steady, not throbbing or pulsating.

- The headache is not accompanied by nausea or vomiting.

- The pain is not worsened by routine physical activity (climbing stairs, walking).

- Some patients may have either sensitivity to light or sensitivity to noise, but not both.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing the cause of persistent daily headache can be difficult. People who visit the emergency room with disabling headache may be misdiagnosed as tension-type headaches instead of migraines. It is important to choose a doctor who is sensitive to the needs of headache sufferers and is aware of the latest advances in treatment.

According to the International Headache Society, a diagnosis of tension-type headache is suggested by the following symptoms:

- Pressing or tightening (but non-pulsating) feeling

- Mild-to-moderate pain on both sides of the head

- Not aggravated by routine physical activity (such as walking or climbing stairs)

In episodic tension-type headaches:

- No nausea or vomiting

- Photophobia (intolerance of light) or phonophobia (intolerance of sound) may be absent or one of these symptoms (but not both) may be present

In chronic tension-type headaches:

- No vomiting

- No moderate or severe nausea

- No more than one of the following symptoms: Mild nausea, photophobia, or phonophobia

- Some types of chronic tension headache may include tenderness upon manual palpitation of the head (pericranial tenderness)

Differentiating Medication-Overuse (Rebound) Headache from Tension-Type Headache.

Many persistent headaches result from the rebound effect caused by the overuse of headache medications.

Usually in such cases, medications have been taken on an ongoing basis for more than 3 days each week. If patients stop taking these drugs, the headaches come back. The patient then starts taking the drugs again. Eventually the headache simply persists and medications are no longer effective. Even after successful medication withdrawal, relapse is common.

Medications associated with medication-overuse headache include barbiturates, sedatives, narcotics, and migraine medications, particularly those that also contain caffeine. (Heavy caffeine use can also cause this condition.) Daily use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like naproxen (Aleve, generic) or ibuprofen (Advil, generic) may also cause medication-overuse headaches.

Differentiating Tension Headaches from Chronic Migraines

Migraines and tension headaches have some similar characteristics, but also some important differences:

- Migraine pain is usually throbbing, while tension-type headache pain is usually a steady ache.

- Migraine pain often affects only one side of the head, while tension-type headache pain typically affects both sides of the head.

- Migraine headaches, but not tension-type headaches, may be accompanied by nausea or vomiting, sensitivity to light and sound, or aura.

Some research suggests that migraine and tension headaches may be related. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #97: Migraine headaches.]

Medical and Personal History

For an accurate diagnosis, the patient should describe the following:

- Duration and frequency of headaches

- Recent changes in their character

- Location of the pain

- Type of pain (throbbing or steady pressure)

- Intensity of the headache

- Associated symptoms, such as visual disturbances or nausea and vomiting. (These are seen most often with migraines.)

- Behaviors during a headache. Different behaviors may help distinguish between migraine and tension headaches. People with tension headaches tend to relieve pain by massaging the scalp, temples, or the nape of the neck. People with migraines are more likely to compress the forehead and temples (tying a scarf around the head) or to apply cold to the area. They also tend to isolate themselves, lie down, induce vomiting, and use more pillows than usual. (None of these maneuvers do much good in relieving either headache, unfortunately.)

The patient should also report any other conditions that might be associated with headache, such as any:

- Chronic or recent illness and their treatments

- Injuries, particularly head or back injuries

- Dietary changes

- Current medications or recent withdrawal from any drugs, including over-the-counter or natural remedies

- History of caffeine, alcohol, or drug abuse

- Serious stress, depression, and anxiety

The doctor will also need the patient's general medical and family history, particularly concerning headaches or other neurological diseases.

Headache Diary to Identify Triggers

Keeping a headache diary is a useful way to identify triggers that bring on headaches, and to help the doctor differentiate between migraine and tension-type headache. Be sure to include all events preceding an attack. Often two or more triggers interact to produce a headache.

In general, certain stimuli are able to trigger most types of primary headaches, although people with migraines may be more sensitive to some of them (weather, certain smells, light, and smoke) than people with tension headaches.

Tracking medications is an important way of identifying medication-overuse headache or transformed migraine.

Be sure to attempt to define the intensity of the headache. There are different scoring symptoms available that help communicate the severity of the pain to the doctor. For instance, the following is a number system that can be helpful:

1 = Mild, barely noticeable

2 = Noticeable, but does not interfere with work/activities

3 = Distracts from work/activities

4 = Makes work/activities very difficult

5 = Incapacitating

Physical Examination

In order to diagnose a chronic headache, the doctor will examine the head and neck to check for muscle tenderness. The doctor may also perform a neurologic examination, which includes a series of simple evaluations to test strength, reflexes, coordination, sensation, and mental function. The doctor may also recommend an eye examination.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests used for severe or persistent headache include computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Imaging tests of the brain may be recommended under the following circumstances:

- If the results of the history and physical examination suggest neurologic problems

- Changes in vision

- Muscle weakness

- Fever and stiff neck

- Changes in the way someone walks

- Changes in mental status including signs of disorientation

Imaging tests may also be recommended for:

- Patients with headache that wakes them at night

- A sudden or severe headache, or a headache that is the worst headache of someone's life

- For patients with history of cancer or weakened immune system

- For new headaches in adults over 50 years, especially in the elderly. In this age group, it is particularly important to first rule out age-related disorders, including stroke, low blood sugar (hypoglycemia), fluid accumulation in the brain (hydrocephalus), and head injuries (usually from falls).

- For patients with worsening headache or headaches that do not respond to routine treatment

Headache Symptoms that Could Indicate Serious Underlying Disorders

Headaches indicating a serious underlying problem, such as cerebrovascular disorder or malignant hypertension, are uncommon. (It should again be emphasized that a headache is not a common first or only symptom of a brain tumor.) People with existing chronic headaches, however, might overlook a more serious condition believing it to be one of their usual headaches. Such patients should immediately call a doctor if the quality of a headache or accompanying symptoms has changed. Everyone should call a doctor for any of the following symptoms:

- Sudden, severe headache that persists or increases in intensity over the following hours, sometimes accompanied by nausea, vomiting, or altered mental states (possible hemorrhagic stroke)

- Sudden, very severe headache, worse than any headache ever experienced (possible indication of hemorrhage or a ruptured aneurysm)

- Chronic or severe headaches that begin after age 50

- Headaches accompanied by other symptoms, such as memory loss, confusion, loss of balance, changes in speech or vision, or loss of strength in or numbness or tingling in arms or legs (possibility of small stroke in the base of the skull)

- Headaches after head injury, especially if drowsiness or nausea are present (possibility of hemorrhage)

- Headaches accompanied by fever, stiff neck, nausea, and vomiting (possibility of spinal meningitis)

- Headaches that increase with coughing or straining (possibility of brain swelling)

- A throbbing pain around or behind the eyes or in the forehead accompanied by redness in the eye and perceptions of halos or rings around lights (possibility of acute glaucoma)

- A one-sided headache in the temple in elderly people; the artery in the temple may be firm and knotty and without a pulse; the scalp may be tender (possibility of temporal arteritis, which can cause blindness or even stroke if not treated).

- Sudden onset and then persistent, throbbing pain around the eye possibly spreading to the ear or neck unrelieved by pain medication (possibility of blood clot in one of the sinus veins of the brain)

Treatment

Management of tension-type headaches focuses in the short term on treating acute attacks, and in the long term on preventing recurrent episodes of headache. In general, short-term treatment of tension-type headache involves drugs (mainly pain relievers) while long-term preventive measures include both drug and non-drug approaches. With medications, relaxation training, lifestyle changes, and other therapies, most headache pain can be relieved or reduced.

Treatment for Acute Attacks of Tension-Type Headaches

Most acute attacks of tension-type headaches get better without any treatment. Simple over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can treat mild symptoms. Aspirin or ibuprofen (Advil, generic) are usually the first choices, followed by naproxen (Aleve, generic). Some patients may also find helpful medications that combine a pain reliever with caffeine.

Some people find massage therapy helpful for treating acute episodes of tension-type headache.

Treatment and Prevention of Frequent and Chronic Tension-Type Headaches

Daily preventive treatment is recommended for patients who experience at least two headache attacks a month. Preventive treatments do not work as well when patients are overusing pain-relief medication, so doctors may recommend stopping and withdrawing from analgesics before beginning preventive approaches.

The goals of preventive treatment are to reduce the frequency and severity of headache attacks, and to improve the response to pain medication.

Preventive treatment for tension-type headache includes:

- Drug treatment with an antidepressant, usually the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline

- Relaxation training and biofeedback

- Stress management through cognitive-behavioral therapy

Studies indicate that best results are achieved when drug treatment is combined with relaxation or stress-management training.

Withdrawing from Medications after Medication-Overuse Headaches

If headaches develop because of medication overuse, the patient cannot recover without stopping the drugs. (If caffeine is the culprit, a person may only need to reduce coffee or tea drinking to a reasonable level, not necessarily stop drinking it altogether.) The patient usually has the option of stopping abruptly or gradually and should expect the following course:

- Most headache drugs can be stopped abruptly, but the patient should be sure to check with the doctor before withdrawal. Certain non-headache medications, such as anti-anxiety drugs or beta-blockers, require gradual withdrawal under medical supervision.

- If the patient chooses to taper off standard headache medications, withdrawal should be completed within 3 days or less. Otherwise, the patient may become discouraged.

- No matter which approach is used for stopping medication, the patient must expect a period of worsening headache for a few days afterward. Alternative pain relievers may be administered during the first days to help withdrawal.

- Most people feel better within 2 weeks, although headache symptoms can persist up to 16 weeks (and in rare cases even longer).

Medications

The standard treatments for tension-type headaches are non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as aspirin and ibuprofen, and tricyclic antidepressants, usually amitriptyline (Elavil, generic).

Due to the risks of overuse and dependence, opoids, opoid-like drugs, and sedative hypnotics are not recommended for treatment of tension-type headaches.

Pain Relievers

Several pain relievers are helpful for mild-to-moderate headaches. They cannot prevent headaches, however.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs). NSAIDs are common pain relievers that block prostaglandins, substances that dilate blood vessels and cause inflammation and pain. NSAIDs are usually the first drugs tried for almost any kind of headache. There are dozens of NSAIDs. Common NSAIDs include:

- Over-the-counter NSAIDs. Aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, generic), naproxen (Aleve, generic), ketoprofen (Nexcede, generic)

- Prescription NSAIDs. Diclofenac (Cataflam, generic), tolmetin (Tolectin, generic), indomethacin (Indocin, generic)

Long-term use of high-dose NSAIDs may increase the risk for stomach bleeding and heart problems, including heart attack and stroke. Daily use of NSAIDs may increase the risk for medication overuse (rebound) headache.

Acetaminophen. Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) is a good alternative to NSAIDs when stomach distress, ulcers, or allergic reactions prohibit their use. A high dose (1,000 mg) is, however, needed for this drug to be effective for headaches.

Acetaminophen does have some adverse effects, and the daily dose should not exceed 4 grams (4,000 mg). Patients who take high doses of this drug for long periods are at risk for liver damage, particularly if they drink alcohol and do not eat regularly. Acetaminophen may cause serious kidney problems in people who already have kidney disease. It also may interact with certain medications, including the blood thinner warfarin (Coumadin).

Tricyclics and Other Antidepressants

Antidepressants known as tricyclics are most often used for prevention of severe chronic tension-type headaches. Newer selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) antidepressants are also sometimes used in milder cases.

Tricyclic Antidepressants. Tricyclics are not only useful for depression but also appear to help relieve muscle pain and improve sleep. They are sometimes classified in one of two categories: tertiary or secondary amines:

- Tertiary amines include amitriptyline (Elavil, generic) and imipramine (Tofranil, generic). Amitriptyline is the tricyclic most commonly used for tension-type headache. These drugs tend to cause more drowsiness than secondary amines, which may be helpful for patients with sleep problems.

- Secondary amines include desipramine (Norpramin, generic) and nortriptyline (Pamelor, Aventyl, generic). Secondary amines may have fewer side effects than tertiary amines, but they are just as toxic in high amounts.

A tricyclic antidepressant is usually started at a lower dose and then slowly increased. A headache diary can help the patient and the doctor assess the effectiveness of the treatment. In general, patients should remain on preventive drug treatment for at least 6 months. After that time, the doctor will slowly reduce the dose while continuing to monitor the frequency of headache attacks.

Side effects are fairly common with these medications. Drowsiness is the most common, but may vary by specific drug. In addition, side effects may include dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, sexual dysfunction, weight gain, trouble urinating, heart rhythm problems, and dizziness. Blood pressure may also drop suddenly when sitting up or standing.

Tricyclics can have serious, although rare, side effects, including heart rhythm problems, which can be dangerous for some patients with certain heart diseases. These drugs can be fatal with overdose.

Other Antidepressants. Selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) work by increasing levels of serotonin in the brain. SSRIs used for tension-type headache preventive treatment include paroxetine (Paxil, generic) and citalopram (Celexa, generic). Other antidepressants used for tension-type headache are mirtazapine (Remeron, generic) and venlafaxine (Effexor, generic), which target both serotonin and norepinephrine.

Although these antidepressants have fewer side effects than tricyclics, they do not appear to be as effective for preventive treatment of tension-type headaches.

Investigational Drugs

Tizanidine. Tizanidine (Zanaflex, generic) is a muscle relaxant that is being studied as a possible preventive drug for chronic tension-type headaches.

Botulinum Toxin. OnabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections are used to relax muscles and reduce skin wrinkles. Botox injections are approved for prevention of chronic migraine in adults. However, Botox has not yet been approved as a treatment for tension-type headaches. Some studies indicate that Botox is not effective for tension-type headache.

Nitric Oxide Synthase Inhibitors. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors block nitric oxide, which may play a role in increasing nerve activity that leads to headache. Drugs are currently being investigated for tension-type headache.

Lifestyle Changes

Psychological and behavioral techniques, and lifestyle changes, can have a beneficial effect on tension-type headaches. These therapies can also enhance the effects of drug treatments. To date, relaxation training and biofeedback have the strongest evidence for improving tension-type headaches.

Relaxation Training and Biofeedback

Relaxation training uses breathing exercises, guided imagery, and other techniques to help relax muscles and relieve stress. Biofeedback uses a device to record a patient’s bodily responses (heart rate, surface skin temperature, muscle tension). This information is then “fed back” to the patient through a sound or visual image. Through this feedback, patients learn to control their physical responses. In clinical studies, relaxation training and biofeedback, both alone and in combination, have led to improvements in tension-type headache.

Stress Management and Behavioral Training

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) teaches patients how to recognize and cope with stressors in their life. It can help patients understand how their thoughts and behavior patterns may affect their symptoms, and how to change the way the body responds to anticipated pain. CBT is often included in stress management techniques. Research indicates that CBT and stress management are most effective when combined with relaxation training or biofeedback.

Massage, Spinal Manipulation, and Physical Therapy

Massage can help relax tense muscles, and may be helpful during acute headache attacks, although there is little evidence for long-term benefits. Although some small studies have suggested that spinal manipulation by chiropractors or osteopaths may have some benefits for preventing tension-type headaches, there is insufficient evidence overall to confirm their effectiveness for tension-type headache pain reduction.

Evidence is somewhat stronger on the benefits of spinal manipulation for patients with headaches originating from nerve or muscular problems in the neck. Some researchers believe that tension-type headaches relieved by spinal manipulation are probably really caused by neck problems.

There has been little research evaluating the benefits of physical therapy for tension-type headache. Still, a physical therapist may be helpful in teaching specific exercises for strengthening and stretching muscles or improving posture. A physical therapist may also be able to advise on ergonomic changes to the patient’s workplace environment.

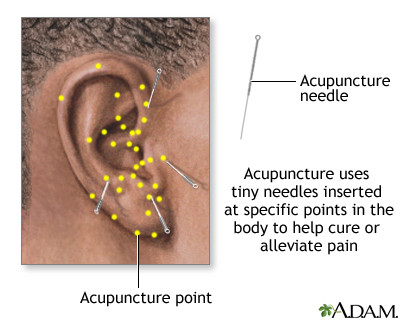

Acupuncture

Several reviews of clinical trials of acupuncture suggest that it may have some benefit for tension headache.

Diet and Exercise

Good health habits -- including adequate sleep, healthy diet, regular exercise -- are helpful for reducing stress. Quitting smoking is important in reducing the risks for all types of headaches.

Home Remedies

Heat or cold packs may be helpful. An ancient remedy for tension headaches uses pressure applied to the head (such as a headband or a towel wrapped around the head) plus either heat or cold. Some people report more relief with cold, others with heat. Packs can either be frozen or heated.

Herbal and Other Natural Remedies

Numerous herbal remedies are promoted for tension-type headache. It is important that anyone taking herbal or so-called natural remedies be aware of the lack of regulations governing their quality and effectiveness. Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need approval from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements. Never give herbal remedies or dietary supplements to children without first consulting a doctor.

Essential Oils. Some patients find relief using two drops of peppermint, eucalyptus, or lavender oil added to one cup of water. The patient soaks a cloth in the solution and applies it as a compress to the head.

Magnesium. Some patients report that magnesium supplements can help prevent migraine headache attacks, but there is little evidence that magnesium is helpful for tension-type headaches.

Herbs. Butterbur and feverfew are two popular herbal remedies for headache relief. The American Academy of Neurology recommends butterbur as “effective” for migraine relief, and feverfew as “probably effective.” It is not clear if these herbs are effective for tension-type headaches.

The following are special concerns for people taking these herbs:

- Butterbur can cause an allergic reaction in people who are sensitive to ragweed and related plants. It is not certain if butterbur is safe for use during pregnancy.

- People who have a bleeding or blood clot disorder, or who take blood-thinning medications such as coumadin (Warfarin, generic), should not take feverfew. Feverfew can interfere with these medications and can affect the time it takes blood to clot. Pregnant women or women hoping to become pregnant should not take this herb, as it may potentially harm the fetus.

Resources

- www.headaches.org -- National Headache Foundation

- www.achenet.org -- American Headache Society

- www.aan.com -- American Academy of Neurology

- www.ninds.nih.gov -- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- www.ihs-headache.org -- International Headache Society

References

Ailani J. Chronic tension-type headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2009 Dec;13(6):479-83.

Antttila P. Tension-type headache in childhood and adolescence. Lancet Neurol. 2006 Mar;5(3):268-274.

Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Hargreaves R. Advances in the pharmacologic treatment of tension-type headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008 Dec;12(6):442-6.

Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Alonso-Blanco C, Cuadrado ML, Gerwin RD, Pareja JA. Myofascial trigger points and their relationship to headache clinical parameters in chronic tension-type headache. Headache. 2006 Sep;46(8):1264-72.

Fernandez-de-Las-Penas C, Cuadrado ML, Pareja JA. Myofascial trigger points, neck mobility, and forward head posture in episodic tension-type headache. Headache. 2007 May;47(5):662-72.

Fumal A, Schoenen J. Tension-type headache: current research and clinical management. Lancet Neurol. 2008; 7(1): 70-83.

Jackson JL, Kuriyama A, Hayashino Y. Botulinum toxin A for prophylactic treatment of migraine and tension headaches in adults: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2012 Apr 25;307(16):1736-45. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.505.

Jackson JL, Shimeall W, Sessums L, Dezee KJ, Becher D, Diemer M, et al. Tricyclic antidepressants and headaches: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010 Oct 20;341:c5222. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5222.

Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, Manheimer E, Vickers A, White AR. Acupuncture for tension-type headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jan 21;(1):CD007587.

Loder, E. and P. Rizzoli. Tension-type headache. BMJ. 2008; 336(7635): 88-92.

Naumann M, So Y, Argoff CE, Childers MK, Dykstra DD, Gronseth GS, et al. Assessment: Botulinum neurotoxin in the treatment of autonomic disorders and pain (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008 May 6;70(19):1707-14.

Rosen NL. Psychological issues in the evaluation and treatment of tension-type headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008 Dec;12(6):425-32.

Silver, N. Headache (chronic tension-type). Am Fam Physician. 2007; 76(1): 114-6.

Stovner Lj, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton R, Scher A, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007 Mar;27(3):193-210.

Vargas BB. Tension-type headache and migraine: two points on a continuum? Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2008 Dec;12(6):433-6.

|

Review Date:

12/17/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |