Melanoma and other skin cancers

Highlights

Overview

- Skin cancers are divided into two major groups:

- Nonmelanoma, which includes basal cell cancer and squamous cell cancer

- Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer

- For the year 2012, the American Cancer Society estimates about 76,250 new cases of melanoma will be diagnosed in the U.S., and about 9,180 Americans will die from the disease.

Risk Factors

- A genetic mutation in a gene called BRAF occurs in approximately 50% of patients with advanced melanoma.

New Drugs

- Vemurafenib (Zelboraf) is an inhibitor of the mutated BRAF protein. Vemurafenib is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating metastatic or inoperable melanoma in patients with the BRAF mutation, and has proven superior to chemotherapy.

- The monoclonal antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy) was approved by the FDA in March 2011 for the treatment of inoperable late stage melanoma. Late stage melanoma patients normally have very few treatment options for their cancer.

Experimental Treatments

- A combination of an experimental melanoma vaccine and interleukin-2 has shown very promising results compared to interleukin-2 alone in late phase testing of patients with advanced stage III or stage IV melanoma.

Risk Factors

- Exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation is a major risk factor for melanoma. UV radiation is present in sunlight and is generated by indoor tanning devices. Heavy exposure early in life is particularly harmful.

- The risk of melanoma increases with increasing frequency and length of time of using indoors tanning devices.

- People with family history of melanoma have approximately twice risk of developing melanoma as those without a family history.

Prevention

- The best way to lower your risk of skin cancer is to protect your skin from the sun and UV light.

- Use sunscreens that block out both UVA and UVB radiation.

- Do not rely on sunscreen alone for sun protection. Also wear protective clothing and sunglasses.

Introduction

Skin cancer is cancer that starts in the skin cells. Skin cancers are divided into two major groups:

- Nonmelanoma, which includes basal cell cancer and squamous cell cancer

- Melanoma, the deadliest form of skin cancer

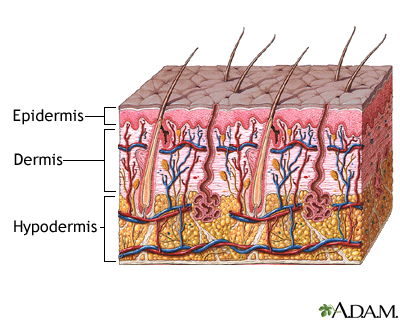

Different skin cancers start in different cells of the skin. To understand how skin cancer develops, it is useful to understand the structure of the skin.

The skin is the largest organ in the body and consists of layers.

- The outermost layer of the skin is called the epidermis. It is only about 20 cells deep, roughly as thick as a sheet of paper.

- The dermis ranges in thickness from 1 - 4 millimeters (about 1/32 - 1/8 inch). The dermis contains tiny blood and lymph vessels, which increase in number deeper in the skin.

Melanocytes. A layer of cells between the epidermis and the dermis called melanocytes produces a brown-black skin pigment (melanin) that determines skin and hair color. Melanin also helps protect against the damaging rays of the sun.

As a person ages, melanocytes often spread (proliferate). They form clusters that appear on the skin surface as small, dark, flat, or dome-shaped spots, which are usually harmless moles or “liver spots."

- When cell proliferation occurs in a controlled and contained manner, the resulting spot is noncancerous (benign) and is commonly referred to as a mole or nevus.

- Sometimes, however, pigment cells grow out of control and become a cancerous and life-threatening melanoma.

Melanoma

Melanoma accounts for less than 5% of all skin cancers, yet it results in most of the skin cancer deaths, according to the American Cancer Society (ACS). For the year 2012, the ACS estimates there will be about 76,250 new cases of melanoma in the U.S., and about 9,180 American deaths from the disease.

At first, melanoma cells are found in the epidermis and top layers of the dermis. However, once they grow downward into the dermis, the cancer can come into contact with lymph and blood vessels, and from there spread to other parts of the body. The thicker the melanoma, the greater the likelihood that it could spread to distant sites.

Removing the lesion before it reaches the deeper layers of the skin is important to achieve a cure.

Specific Melanomas

Superficial Spreading Melanoma. Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common and most curable type of melanoma. It is flat, asymmetrical, unevenly colored, and usually grows outward across the surface of the skin. Superficial spreading melanoma accounts for about 70% of melanomas. In men, it occurs most often on the back. In women, it is most likely to be seen on the back of the leg.

Nodular Melanoma. Nodular melanoma appears as a fast-growing brown or black lump, and its characteristics do not always fit the definitions described above. It is important to check for this type of melanoma because it is associated with an outbreak of other tumors. Nodular melanoma accounts for about 5% of melanomas. It is usually seen on the trunk or limbs.

Lentigo Maligna. Lentigo maligna (sometimes called Hutchinson's freckle) usually occurs in elderly people and is marked by flat, mottled, tan-to-brown freckle-like spots with irregular borders. These lesions often appear on the face or other sun-exposed areas and typically grow slowly for 5 - 15 years before cancer appears. Lentigo maligna melanoma accounts for 4 - 15% of melanoma cases.

Acral Lentiginous Melanoma. Although rare, acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma among African and Asian populations. It commonly appears as a dark patch on the palms, soles, fingers, or toes, under fingernails or toenails, or in mucus membranes.

Several other types of melanomas exist, but they are relatively uncommon.

Growth Pattern

Melanoma cells usually spread first through the lymph vessels or glands. Melanoma cells can also spread by way of blood vessels to various organs, carrying cancer to the liver, lungs, brain, or other sites.

Melanomas tend to grow in stages:

- Most melanomas tend to be flat at first, and spread across the skin surface as they grow. At this early stage, which can last 1 - 5 years or longer, removing the growth has an excellent chance of curing the melanoma. Still, there is a possibility that some of these melanomas are invasive, and they should be treated aggressively.

- Lesions that become raised or dome-shaped over at least part of their surface indicate that downward growth has occurred. In some cases, this growth is very rapid, occurring over a period of weeks to months.

Have any suspicious lesion checked immediately, especially if it has grown quickly or is partially flat and partially raised.

Location

Common sites of melanoma in men include:

- Head

- Neck

- Middle of the body (trunk)

Common sites of melanoma in women include:

- Arms

- Legs

However, melanoma can affect any area of the skin. You may not notice melanomas if they appear on areas that are difficult to examine, such as the scalp or back.

Less common sites for melanoma include:

- Fingers

- Genitals

- Lips

- Palms

- Soles of the feet

- Under the fingernails or toenails

A dark lesion under the nail that runs into the nearby skin and doesn't heal may be a sign of melanoma.

Rarely, melanomas appear in the mouth, iris of the eye, or retina at the back of the eye, where they may be found during dental or eye examinations. While quite rare, melanoma can also develop in the mucus membranes, such as the vagina, esophagus, anus, urogenital tract, and small intestines.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Other types of skin cancer are referred to as nonmelanoma skin cancers. The two most common types are called basal cell cancer and squamous cell cancer.

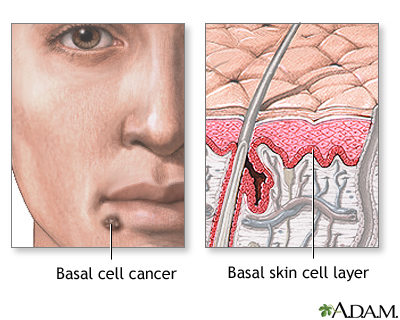

Basal Cell Cancer

Basal cell cancer starts in the lowest part of the epidermis, in round cells called basal cells. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common form of skin cancer. However, this cancer is far less likely to be fatal than melanoma. The death rate from nonmelanoma skin cancers has dropped about 30% over the past 30 years.

Basal cell cancer usually develops later in life in areas that have received the most sun exposure, such as the head, neck, back, and especially the nose. However, some basal cell cancers appear in areas not exposed to the sun.

Basal cell cancers have many different appearances:

- They usually appear as a round area of thickened skin that does not change color or cause pain or itching.

- Very slowly, the lesion spreads out and develops a slightly raised edge, which may be translucent and smooth. Rarely, basal cell cancers have a similar color to malignant melanomas.

- Eventually, the center becomes hollowed and covered with a thin skin, which can become sore and open.

- A form known as aggressive-growth basal cell cancer looks like a scar with a hard base. This type of cancer is more likely to spread and must be treated very aggressively.

Basal cell cancers are sometimes hard to tell from benign skin conditions. For instance, occasionally they arise in unexposed skin, where they may look like an ordinary mole, cyst, or pimple. They may be particularly difficult to tell apart from benign cysts when they occur near the eyes.

Usually, basal cells grow slowly. They are rarely deadly. Most basal cell cancers do not need to be treated as an emergency. However, because late treatment can cause disfigurement, they should be removed as early as possible.

Basal cell cancers that are most likely to spread include those that are larger than 1 centimeter, scar-like, and those located on the cheek, nose, neck, earlobe, eyelid, or temple.

Some studies have shown that people with basal cell cancer may be at higher risk for second cancers, including melanoma, cancer of the lip, salivary glands, larynx, lung, breast, kidney, and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Those at higher risk for such cancers appear to be men and anyone diagnosed before the age of 60 with basal cell cancer.

Squamous Cell Cancer and Bowen's Disease

Squamous cell cancer of the skin is even less common than basal cell cancers.

Squamous cell cancer develops from flat, scale-like skin cells called keratinocytes, which lie under the top layer of the epidermis. Most squamous cell cancers occur on sun-exposed areas, especially the forehead, temple, ears, neck, and back of the hands. People who have spent considerable time sunbathing may develop them on their lower legs. Squamous cell cancers occur more often than basal cell cancers in African-Americans and Asians, and are more common in men than women.

Although squamous cell skin cancers usually can be removed completely with no risk of the cancer spreading, they are more likely, compared to basal cancers, to be invasive and to spread elsewhere in the body.

Types of squamous cell cancer:

- Squamous cell carcinoma in situ (also called Bowen's disease) is the earliest form of this type of cancer. The cancer has not invaded surrounding tissue. Cancer areas appear as large reddish patches (often over 1 inch) that are scaly and crusted.

- Invasive squamous cell carcinoma is highly likely to spread (metastasize). The skin cancer lesions can grow rapidly (over months) or slowly (over years). Eventually they break into an open wound (become ulcerated).

Getting prompt treatment is important, because squamous cell cancers are more likely than basal cell cancers to spread to local lymph nodes.

Squamous cell cancers most likely to spread include:

- Deep lesions, or patches with poorly defined borders

- Large lesions (larger than 2 cm in diameter)

- Lesions that keep returning

- Squamous cell cancer on the hands, neck, earlobe, eyelid, lips, or temple

- Squamous cell cancer that develops in ulcers

- Squamous cell cancer that develops on skin areas that have been treated with radiation or exposed to cancer-killing chemicals (chemotherapy)

People who have had basal cell or squamous cell skin cancers face a two-fold increase in their risk of developing other types of cancer including:

- Bladder cancer

- Breast cancer in women

- Leukemia

- Lung cancer

- Melanoma

- Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

- Testicular and prostate cancer in men

The younger people are when they get nommelanoma skin cancer, the higher their risk for developing other cancers.

Precancerous Skin Conditions

Actinic (Solar) Keratosis. Actinic keratosis (also called solar keratosis) is a skin lesion caused by too much sun exposure. There is some increased risk of skin cancer in patients who have these lesions, but the risk of one specific actinic keratosis turning into cancer is low. The increased risk of cancers may be due to the fact that heavy sun exposure has been linked to both actinic keratosis and nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Actinic keratosis occurs after years of sun exposure. It appears mostly on sun-exposed skin, such as the face, neck, back of the hands and forearms, upper chest, and upper back. Men may develop keratosis along the rim of the ear.

Actinic keratosis have the following characteristics:

- Lesions typically occur on the surface of the skin and have a sandpaper-like feel. In fact, they are sometimes more easily felt than seen.

- Most lesions are pink and even flesh-colored. Some are red or brown, scaly, and tender. At times, they can resemble melanomas; even dermatologists may have trouble telling the two apart.

- They can range in size from microscopic to several inches in diameter.

Keratoacanthomas. Keratoacanthomas closely resemble squamous cell cancers, but they are not cancerous. Most of these occur in sun-exposed skin, usually on the hands or face. They are typically skin colored or slightly red when they first develop, but their appearance typically changes:

- In the early stages, keratoacanthomas are smooth, red, and dome shaped.

- Within a few weeks, they can grow rapidly, usually to 1 or 2 centimeters. Some reach the size of a quarter in less than a month and can be disfiguring.

- They eventually stop growing and become crater-like, with a surrounding outer rim of tissue and sometimes a crusty interior.

Most will get better on their own within 1 year, but they almost always scar after healing. Also about 25% develop into squamous cell cancers, most frequently in older people and in sun-exposed areas. Removal by surgery (sometimes by radiation) is recommended. They may also be treated with 5-fluorouracil, either as a cream or injections.

Causes

The sun is the most important cause of prematurely aging skin (photoaging) and skin cancers.

Long-term, repeated exposure to sunlight appears to be responsible for most undesirable consequences of aging skin, including basal cell and squamous cell cancers.

Melanoma is more likely to be caused by intense exposure to sunlight in early life.

UVA and UVB Radiation. When sunlight penetrates the top layers of the skin, ultraviolet (UVA or UVB) radiation strikes the DNA inside the skin cells and damages it.

- UVB is the main type of radiation responsible for sunburns. It primarily affects the outer skin layers. This type of ultraviolet light is most intense at midday when sunlight is brightest.

- UVA penetrates more deeply and efficiently. Although window glass filters out UVB, it does not protect against UVA rays.

Damaging Effects of UV Radiation. Both UVA and UVB rays cause damage, including genetic injury, wrinkles, lower immunity against infection, aging skin disorders, and cancer, although the mechanisms are not yet fully clear. The following are some ways in which cancer may develop, and some actions the skin uses to defend itself against DNA damage.

- Oxidation and Antioxidants. UV radiation promotes the production of oxidants, also called free radicals. Free radicals are unstable molecules produced by normal chemical processes in the body that, in excess, can damage the body's cells and even alter the DNA. This contributes to the aging process and sometimes to cancer.

- Defective DNA Repair and Protective Enzymes. Some skin cancers are caused by a breakdown in the body's mechanisms that help repair DNA damage. For example, xeroderma pigmentosum (XP) is a rare genetic disease in which the body cannot repair damage caused by ultraviolet light. Normally, a number of enzymes in the skin help protect against this damage.

- Breakdown of Immune Protection. Specific immune factors protect the skin, including white blood cells called T lymphocytes and specialized skin cells called Langerhans cells. These immune system cells attack developing cancer cells at the very earliest stages. However, certain substances in the skin, particularly a chemical called urocanic acid, can suppress such immune factors when exposed to sunlight.

Defective Cell Death (Apoptosis). Apoptosis is the last defense of the immune system. It is a natural process of cell-suicide, which occurs when cells are very severely damaged. Apoptosis in the skin kills off cells harmed by UVA so that they do not turn cancerous. The peeling after sunburn is the result of these dead skin cells. However, some gene defects or other factors can interfere with apoptosis. If this occurs, damaged cells can continue to spread, resulting in skin cancer.

Risk Factors

According to the American Cancer Society the lifetime risk of getting melanoma is about 2% (1 in 50) for whites, 0.1% (1 in 1,000) for blacks, and 0.5% (1 in 200) for Hispanics. The number of melanoma cases has been increasing over the past 30 years.

Survival rates have been improving, however, and the increase in melanomas has occurred mainly with less aggressive forms of the disease. Some experts believe this is due to earlier diagnosis and increased awareness of the disease, resulting from effective public health programs.

The following factors increase your risk for skin cancer:

- Age over 40

- Being male

- Fair skin

- Too much exposure to sunlight and ultraviolet radiation, including indoor tanning

- High mole count, particularly on the arms

- Personal history of skin cancer

- Family history of skin cancer

- Smoking

- Certain chronic or severe skin problems

- Certain medical conditions or treatments that affect your immune system

- Exposure to chemicals or radiation

- Taking TNF-alpha blockers to treat rheumatoid arthritis or other illnesses

Age and Gender

Aging may weaken the body's ability to fend off cancers, including melanomas. As a person ages, they lose Langerhans cells that help fight off early skin cancers, possibly setting the stage for skin cancers in later life.

Melanoma in Adults. Melanoma is most common in people over 40, although it also can affect young and middle-aged people. The average age at diagnosis is 57 years. Men are more likely to have invasive and fatal melanoma than women, although some research suggests that the higher rates are only because men fail to get suspicious skin changes diagnosed before they become dangerous. The rate in women levels off somewhat after age 50; researchers think menopause could have some sort of protective effect.

Melanoma in Children. Melanoma is rare in children under age 10. Among children ages 10 - 14 the incidence is only 0.3 per 100,000 children. Between ages 14 - 19, it is still very rare, with only 1.3 cases per 100,000 children. Parents should not be too alarmed by every minor skin imperfection in their children. However, melanoma is as serious in children as it is in adults, and early detection is still critical.

Nonmelanoma skin cancers are rare in children and young adults, but they begin to increase significantly in middle age and older.

Sunlight and Ultraviolet Radiation Exposure

Skin cancer is associated with both the length and intensity of sun exposure. The risk of melanoma increases with excessive sun exposure during the first 10 - 18 years of life. Sunburns are also dangerous; having five or more sunburns doubles the risk of developing skin cancer. The cancer typically arises many years later.

Tanning Devices. Tanning beds and sun lamps increase the risk for developing melanoma, and the risk increases with frequency and length of use. Women in their 20s, as well as blondes and redheads, are especially at risk.

Phototherapy and Photochemotherapy with PUVA. There is some evidence that long-term treatment for psoriasis and other skin conditions using UVA radiation (PUVA) may increase the risk for melanoma.

Ethnic Groups and Complexion. People with light skin; blue, gray, or green eyes; red or blond hair; and lots of freckles are at highest risk for developing all types of skin cancers. The risk increases for those who easily sunburn and rarely tan, particularly if they live close to the equator where sunlight is most intense. However, people with darker complexions are not immune.

A classification system has been created for skin phototypes (SPTs) based on the sensitivity to sunlight. It ranges from SPT I (lightest skin plus other factors) to IV (darkest skin). People with skin types I and II are at highest risk for photoaging skin diseases, including cancer. It should be noted, however, that premature aging from sunlight can affect people of all skin shades.

Tanning and Sunburn Risk | |

Skin Type | Tanning and Burning Risk |

I | Always burns, never tans, sensitive to sun exposure. |

II | Burns easily, tans minimally. |

III | Burns moderately, tans gradually to light brown. |

IV | Burns minimally, always tans well to moderately brown. |

V | Rarely burns, tans profusely to dark. |

VI | Never burns, deeply pigmented, least sensitive. |

Geographic Location

Geography plays a role in skin cancer risk, primarily with regard to the intensity and length of sun exposure in certain locations. Studies show an increased incidence of melanomas in populations that previously had a lower incidence, but then migrated to Australia.

Genetic Factors

People with certain genetic characteristics, such as blue or green eyes, or blonde or red hair, have an increased risk of skin cancers.

Patients diagnosed with melanoma, and who have a family history of melanoma or nevi, are considered to be at increased risk for more invasive cancers. A number of genetic factors are being investigated for their role in melanomas, including inherited genes and genetic defects that are acquired through the environment (particularly sunlight).

Your genetic makeup, and whether or not certain genes mutate in your body can increase your risk of developing melanoma and other skin cancers.

A genetic mutation in a gene called BRAF occurs in approximately 50% of patients with advanced melanoma.

Personal or Family History of Skin Cancer

Melanoma. Individuals who have been diagnosed with melanoma are at increased risk for a second primary melanoma. That risk may be as high as 5%, and is higher in older men and in those whose first melanoma was on the upper body and face.

People with family members who have or had melanoma have approximately a twofold risk of developing melanoma as those without a family history, and should be examined on a regular basis.

Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers. The evidence for an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers with a family history of such cancers is increasing, but it is still weaker than the evidence for a familial connection to the risk of melanoma.

Skin Conditions that Increase Skin Cancer Risk

Moles (Nevi) and Other Dark Blemishes. Certain moles and dark blemishes increase the risk for skin cancer. Any mole (nevus) or other blemish that seems new, changing, or unusual in any way should be evaluated by a health care professional as an existing mole can become cancerous. Although 80% of melanoma cases develop from brand new lesions or moles, your risk of developing the condition increases if you have the tendency to develop moles.

Some specific moles or dark blemishes that are risk factors for melanoma include:

- Freckles. Freckles typically appear in children on sun-exposed areas and are usually evenly brown or tan. The more freckles a person develops as a child, the greater the risk for melanoma in adulthood.

- Dysplastic (or Atypical) Nevi. About 30% of the population has moles called dysplastic nevi, or atypical moles. They are larger than ordinary moles (most are 5 mm across, about the size of a pencil eraser, or larger), have irregular borders, and are various shades or colors. Individuals who have dysplastic nevi plus a family history of melanoma (a syndrome known as FAMM) are at a high risk for developing melanoma at an early age (younger than 40). The risk for those with atypical moles and no family history of melanoma is less clear.

- Large birthmarks (giant congenital nevi). Very large birthmarks more than 8 inches across are major risk factors for melanoma. In such cases, cancer usually appears by age 10. Medium-sized congenital nevi do not appear to increase the risk for melanoma. Whenever possible, very large birthmarks should be removed during infancy. Experts disagree, however, about whether small birthmarks need to be removed. Parents should watch any birthmark for changes.

The more moles a person has, the higher the risk that one of those moles will become cancerous, although the danger is still very small. The risk is higher, however, with atypical moles.

Some skin blemishes can look like -- but are not -- melanoma. Noncancerous moles typically have the following characteristics:

- They generally remain small with clearly defined, regular borders, and uniform color. Some have a regular spotted or net-like pattern of pigmentation, however, and may even resemble early melanoma.

- They typically first appear during childhood, puberty, or young adulthood. They may naturally grow, darken, or increase in number at certain times of life, such as adolescence or pregnancy.

Examples of moles or blemishes that may resemble skin cancer include:

Blue nevus. A benign mole that may easily be mistaken for melanoma. It is a blue-black, smooth, raised nodule and commonly occurs on the buttocks, hands, or feet.

Liver Spots. Liver spots are usually evenly brown or tan spots caused by the sun. They are universal signs of aging. Occurring most noticeably on the hands and face, these harmless blemishes tend to enlarge and darken over time.

Spindle Cell (Spitz) Nevus. Children may develop a benign lesion called a spindle cell (or Spitz) nevus. The mole is firm, raised, and pink or reddish-brown. It may be smooth or scaly and usually appears on the face, particularly on the cheeks. It is not harmful, but it may be difficult to tell apart from a melanoma, even for experts.

Diseases and Treatments that Increase Skin Cancer Risk

Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Survivors of either non-Hodgkin's lymphoma or melanoma face a higher risk for the other cancer. These diseases may have common causes, such as exposure to UV radiation or shared genetic factors.

Human papillomavirus (HPV). Genital warts (caused by human papillomavirus, or HPV) may also increase the risk of squamous cell cancer in the genital and anal areas and around fingernails.

Endometriosis. The condition in which cells that line the uterus also grow in other parts of the abdomen may be linked to a higher risk of melanoma. In one large study, women with a history of endometriosis had a 60% increased risk of developing melanoma. Those with uterine fibroids (benign tumors in the uterus) were also at increased risk.

Immunosuppression

Skin cancer risk is increased in people whose immune systems are suppressed because of certain medications, organ transplantation, or medical conditions such as AIDS. Melanoma has also developed in patients who received solid organ transplants from donors who had the disease.

Immune-suppressing drugs used to treat autoimmune disorders may also increase the risk of skin cancer. For example, patients who take TNF-alpha blockers to treat rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases carry an increased risk for both melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers. Potential skin cancer risks have been associated with the eczema drugs pimecrolimus (Elidel) and tacrolimus (Protopic) in a small number of people. It is not known for sure whether these drugs, when used topically on the skin, actually cause cancer.

Occupational Radiation and Chemical Exposure

Occupational exposure to radiation and some chemicals (vinyl chloride, polychlorinated biphenyls, and petrochemicals) in health care or industrial settings may increase the risk for melanoma. However, the evidence for this increased risk is not very strong. Airline pilots have been found to have an increased risk for melanoma. It is uncertain, however, whether this higher risk is from excessive exposure to ionizing radiation at high altitudes, or because they have more opportunity to spend time in sunny regions.

Prevention

The best way to lower your risk of skin cancer is to protect your skin from the sun and UV light. That means avoiding excess sun exposure, especially in midday when the sun is strongest.

Wear sunscreen. The use of sunscreens is complex, and everyone should understand how and when to use them. Follow instructions closely and reapply as directed after swimming or sweating. The bottom line is not that people should avoid sunscreens or sunblocks, but that they should always use them in combination with other sun-protective measures.

Many parents are now taking effective steps to protect their children, although experts worry that they are relying too much on sunscreen and less on other protective measures.

Guidelines for Avoiding the Sun and UV Radiation

The following are some specific guidelines for avoiding excessive sun exposure:

- Use sunscreens that block out both UVA and UVB radiation. Do not rely on sunscreen alone for sun protection. Also wear protective clothing and sunglasses.

- Avoid sun exposure, particularly during the hours of 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., when UV rays are the strongest.

- Use precautions, even on cloudy days. Clouds and haze do not protect you from the sun, and in some cases may intensify UVB rays.

- Avoid reflective surfaces such as water, sand, concrete, and white-painted areas.

- UV intensity depends on the angle of the sun, not heat or brightness. The dangers are greater closer to the start of summer.

- Skin burns faster at higher altitudes. One study suggested that an average complexioned person burns in 6 minutes at 11,000 feet at noon compared to 25 minutes at sea level.

- Avoid sun lamps, tanning beds, and tanning salons. The machines use mostly high-output UVA rays.

Sun-Protective Clothing

Wear protective clothing, sunglasses, and a hat to shield your face from the sun's rays. Special clothing can block out UV rays. This clothing is rated using sun protection factor (SPF) or a system called the ultraviolet protection factor (UPF) index, with 50 UPF being the highest. (According to one study, this is a very reliable indicator of protection.) The clothing is expensive, however.

- Everyone, including children, should wear hats with wide brims. (Even wearing a hat, however, may not fully protect against skin cancers on the head and neck.)

- Look for loose-fitting, unbleached, tightly woven fabrics. The tighter the weave, the more protective the garment.

- Washing clothes over and over improves UPF by drawing fabrics together during shrinkage. An easy way to assess protection is simply to hold the garment up to a window or lamp and see how much light comes through. The less light the better.

- Everyone over age 1 should wear sunglasses that block all UVA and UVB rays when in the sun.

Sunscreen Guidelines

When choosing a sunscreen, look at the ingredients. Preparations that help block UV radiation are sometimes classified as sunscreens or sunblocks, according to the substances they contain. In general, sunscreens contain organic formulas and sunblocks inorganic formulas. However, the term sunblock is used less and less as sunscreens increasingly contain both kinds of ingredients:

- Organic formulas contain UV-filtering chemicals such as octocrylene, octyl salicylate, homosalate, and octyl methoxycinnamate (block UVB), avobenzone-Parsol 1789 (blocks UVA), cinoxate, ethylhexyl p-methoxycinnamate (blocks UVB and small amounts of UVA), oxybenzone, and benzophenone-3 (blocks UVA/UVB). Look for a wide-spectrum sunscreen that contains combinations of these ingredients and filters both UVA and UVB light.

- Inorganic formulas contain the UV-blocking pigments zinc oxide or titanium dioxide. Zinc and titanium oxides lie on top of the skin and are not absorbed. They prevent nearly all UVA and UVB rays from reaching the skin. Older sunblocks were white, pasty, and unattractive, but current products use so-called microfine oxides, either zinc (Z-Cote) or titanium. They are transparent and nearly as protective as the older types.

Inexpensive products with the same ingredients work as well as expensive ones.

Under new FDA guidelines proposed in 2011, sunscreen products will carry a 4-star rating for UVA protection levels (1 star being the weakest protection, no stars meaning no UVA protection). In addition, sunscreens will carry the normal SPF rating, but it will be specific to UVB protection. The new suncreen labels will also stress the importance of protective clothing for complete sun protection.

The safety and efficacy of combination sunscreen and insect repellant products remain unclear. While suncreen should be re-applied frequently, insect repellant applied too often could be toxic.

Organic formulas and inorganic microfine oxides do not protect against visible light, which is a problem for people who have light-sensitive skin conditions, including actinic prurigo, porphyria, and chronic actinic dermatitis.

Calculating SPF. SPF is a ratio based on the amount of UVB radiation needed to turn sunscreen- or sunblock-treated skin red compared to non-treated skin. For instance, people who sunburn in 5 minutes and who want to stay in the sun for 150 minutes might use an SPF 30 sunscreen. The formula would be: 30 (the SPF number) times 5 (minutes to burn) = 150 minutes in the sun.

Protection offered by sunscreens may be classified as follows:

- Minimal: SPF 2 to 11

- Moderate: SPF 12 through 29

- High: SPF 30+

Under the new FDA guidelines proposed in 2011, the maximum UVB protection factor would be raised from SPF 30 to 50.

SPF Levels by Age Group. Although sunscreens are safe in most toddlers and children, they should not be the first and only lines of defense. All young children should be well-covered with clothing, sunglasses, and hats. Keep children out of the sun during peak sunlight periods. Do not use sunscreens on babies younger than 6 months without consulting a doctor.

Older children and adults (even those with darker skin) benefit from using SPFs of 15 and over. Some experts recommend that most people should use SPF 30 or higher on the face and 15 or higher on the body. Adults who burn easily instead of tanning and anyone with risk factors for skin cancer should use SPF 30 or higher.

Timing and Amount of Application. Apply sunscreen or sunblock liberally as follows:

- Adults should wear sunscreen every day, even if going outdoors for only a short time.

- Apply a large amount to all exposed areas, including ears and feet. To get the level of protection indicated by the sunscreen's SPF, experts recommend half a teaspoon each for the head, neck, and each arm and a teaspoon each for the chest area, back, and each leg.

- Apply sunscreen or sunblock 30 minutes before venturing outdoors for best results. This allows time for the sunscreen to be absorbed. Then reapply every 15 - 30 minutes while out in the sunlight.

- Also reapply each time after exercise or swimming, or at least every two hours. Choose a waterproof or water-resistant formula, even if your activities don't include swimming. Waterproof formulas last for about 40 minutes in the water, whereas water-resistant formulas last half as long.

Possible Hazards of Relying on Sunscreens. When used generously and appropriately, sunscreen products and sun avoidance help reduce the severity of many aging skin disorders, including squamous cell cancers. There are certain concerns, however. Sunscreens do not appear to protect against melanoma and some basal cell cancers. It is also important to remember that even with the use of sunscreens, people should not stay out too long during peak sunlight hours. Even if a person doesn't sunburn, UVA rays can still penetrate the skin and do harm. In addition, some people use too little sunscreen, therefore unknowingly increasing their risk of aging skin disorders.

Chemoprevention

Chemoprevention is the use of a substance to prevent or reduce your risk of cancer. Certain drugs have been used to help block the development of skin cancers, including melanoma. These include A medicine called imiquimod, which is approved to prevent skin cancer in certain people. This medicine prompts the immune system to fight off foreign substances, including cancer cells.

Chemopreventive drugs under investigation that show promise for skin cancer include:

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Retinoids, which have been shown to prevent nonmelanoma skin cancer in patients with basal cell nevus syndrome, xeroderma pigmentosum, and transplanted organs. Oral retinoids include isotretinoin and acitretin. These medications may also prevent the development of squamous cell carcinoma in patients who are taking them to treat psoriasis.

Antioxidants, Vitamins, and Herbal Products

Antioxidants are chemicals or drugs that help prevent cell damage from unstable molecules called free radicals. Antioxidants promoted to protect the skin include vitamins C and E, and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10).

There are wide claims about the benefits of antioxidants for wrinkles when used in skin creams. To date, only skin products containing selenium and vitamins E and C have been shown to help reduce sun damage to the skin. However, most available brands contain very low concentrations of these antioxidants. In addition, antioxidants are not well absorbed by the skin, so the effect may be short-term. There is also no evidence that they prevent skin cancer.

Warning: A wide range of herbal products may contribute to skin problems. Some Chinese herbal creams have been found to contain corticosteroids. Mercury or arsenic contaminants have been found in some Ayurvedic therapies. In addition, several oral herbal remedies used for medical or emotional conditions may produce photosensitivity (irritation in reaction to sunlight). They include, but are not limited to, St. John's wort, kava, and yohimbe.

Screening

Education and prevention programs have led to improved screening for skin cancer, which in turn has improved diagnosis and survival rates for melanoma.

Self-Examination for Warning Signs of Skin Cancer

Skin cancers may have many different appearances. They can be small, shiny, or waxy, scaly and rough, firm and red, crusty or bleeding, or have other features. Itching, tenderness, scaling, bleeding, crusting, or sores can signal potentially cancerous changes in any mole.

There are a number of factors to look for, which can serve as a general guide. They fall under the skin cancer ABCDE rule:

- Asymmetry (A). Skin cancers usually grow in an irregular, uneven (asymmetric) way. That means one half of the abnormal skin area is different than the other half.

- Border (B). Moles with jagged or blurry edges may signal that the cancer is growing and spreading.

- Color (C). One of the earliest signs of melanoma may be the appearance of various colors in the mole. Because melanomas begin in pigment-forming cells, they are often multicolored lesions of tan, dark brown, or black, reflecting the production of melanin pigment at different depths in the skin. Occasionally, lesions are flesh colored or surrounded by redness or lighter areas.

- Pink or red areas may result from inflammation of blood vessels in the skin.

- Blue areas reflect pigment in the deeper layers of the skin.

- White areas can arise from dead cancerous tissue.

- Diameter (D). A diameter of 6 millimeters or larger (about the size of a pencil eraser) is worrisome. Researchers are finding that moles greater than 6 millimeters are more likely to be melanoma. Larger moles correlate to a more invasive cancer. By the time a lesion has grown this large, there will most likely be other abnormalities. A doctor should examine any suspicious lesion, no matter what its size.

- Evolution (E). A lesion that has changed in size, color, or appearance should be examined.

Keep in mind that the most important warning sign of melanoma is a new or changing skin lesion, regardless of its size or color. Changes that occur over a short period of time (particularly over a few weeks) are most concerning.

Anyone with risk factors for skin cancer should check their entire body about once a month. People who regularly check moles on their skin may have a lower risk of developing advanced melanoma.

It helps to draw a map of the body, indicating locations of moles, areas of discoloration, lumps, or other blemishes. Whenever you do a self-examination, compare your body to the map to check for new lesions, lumps, or moles and for changes in shape, color, and size.

There are three specific body areas to look for skin cancers, including melanomas:

- Areas visible to anyone, such as the arms or face -- about 60% of melanomas are found on these areas.

- Areas usually covered with clothing and visible only to the patients or their partners -- about 34% of melanomas are found in these areas.

- Hidden areas such as the scalp, buttock folds, and mouth -- about 6% of melanomas, usually more advanced, are found here.

Ask a partner to help you check these areas. Turn on a hair dryer to separate your hair and examine the scalp.

Professional Examination for High-Risk Individuals

Everyone, but especially those with a high risk of developing melanoma, may benefit from a whole body skin exam performed by a dermatologist. People in the high-risk group include those with a personal or family history of melanoma, and individuals with atypical nevi (irregular moles that are larger than normal).

Such people should protect themselves from overexposure to sunlight and have a medical examination of the entire skin surface every 3 - 12 months (the frequency depends on your risk factors). The doctor may take photographs of specific moles, or your entire body, at each visit and compare them with previous photos to look for any changes.

Examinations for Patients Previously Treated for Melanoma. People who have had melanoma and have been treated successfully are at risk for the cancer returning (recurrence) or for developing another primary melanoma. Based on recurrence rates by cancer stage, doctors suggest the following guidelines for being reexamined by a doctor after treatment:

- Stage I patients: Yearly exam

- Stage II patients: Every 6 months for the first 2 years, and annual exams afterward

- Stage III patients: Every 3 months for the first year, every 4 months for the second year, and every 6 months for years 3 to 5

All patients should be checked annually after year 5. These are guidelines only and may depend on the individual patient.

Diagnosis

An experienced doctor should first rule out noncancerous (benign) conditions that resemble melanoma, such as a mole called a melanocytic nevus.

In rare instances, a melanoma will be difficult to detect. For example, an uncommon form called a myxoid melanoma may be mistaken for a benign skin disorder known as a myxoid fibrohistiocytic lesion. Additional diagnostic procedures such as a biopsy (see below), computerized image processing, or advanced staining techniques may help to confirm or rule out the diagnosis of melanoma.

Melanoma also tends to be diagnosed at a later stage in people with darker skin.

Dermoscopy and Total Body Photography

A combination of imaging approaches should be considered for early melanoma detection and diagnosis, since each technique alone has limitations. Some doctors now use various handheld scope-like devices (dermoscopy, dermatoscopy, or epiluminescence microscopy) that enhance the visualization of the suspected lesion.

Skin Biopsy

A skin biopsy is the removal of skin tissue for examination under a microscope. The exact type of biopsy depends on how deep the lesion has penetrated the skin.

- Shave biopsy uses a thin surgical blade, or scalpel, to shave off the top layers of skin. The doctor may use this type of biopsy to diagnose basal cell cancer.

- Punch biopsy uses a round, cookie-cutter-like tool. It is used to take a deeper sample of the skin.

- Incisional and excisional biopsies remove tumors that have grown deep into the skin. An incisional biopsy cuts out part of the tumor. An excisional biopsy removes the entire tumor. These biopsies are used to diagnose melanoma.

All of the above-mentioned biopsies can be done using local anesthesia.

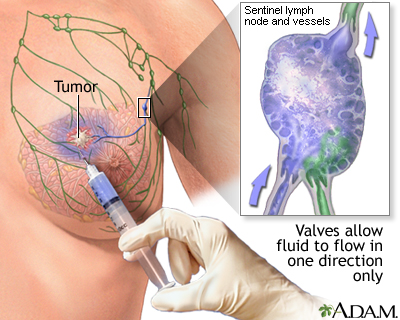

Lymph Node Biopsy

A lymph node biopsy may be needed for patients with recently diagnosed melanoma, to help determine whether the cancer has spread to one or more lymph nodes.

A procedure called sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy is now recommended for cancers that are thicker than 1 millimeter. It is usually not necessary for cancers thinner than 0.75 millimeter, unless they have opened (ulcerated). Although some evidence suggests an SLN biopsy may improve survival, no clinical trials to date have proven that it improves the outlook in people with thin melanoma.

An SLN biopsy involves the following:

- A tiny amount of a tracer, either a radioactively labeled substance or a blue dye, is injected into the tumor site.

- The substance flows through the lymph system into the sentinel node, the first lymph node to which any cancer would spread in a given area.

- The sentinel lymph node and possibly one or two other nodes are removed and biopsied.

The results of the biopsy can help doctors decide whether or not to remove other lymph nodes:

- If the sentinel node and other nodes show signs of cancer, the nearby lymph nodes are removed.

- If they do not show signs of cancer, the rest of the lymph nodes will likely be cancer-free, and further surgery is not needed.

Secondary Tests

Patients with nom-melanoma skin cancers generally require no further workup.

Those with melanoma may need the following:

- Blood tests that examine the levels of the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase. Elevated levels of this enzyme suggest that the cancer has spread.

- Blood tests to assess liver function and other factors, such as anemia. These tests help determine specific sites where the cancer may appear.

- Computed tomography (CT) scans of the chest, abdomen or pelvis, which may be used to identify whether the melanoma has spread at the time of diagnosis. These scans are also used to monitor the patient after treatment.

- Positron emission tomography (PET) may also be used. PET may help find evidence that the cancer has spread elsewhere in the body. Such evidence does not always show up during a physical exam or CT scan.

Staging

Staging is the process used to determine the size of the tumor and where and how far it has spread (metastasized). Staging helps the health care team plan for appropriate treatment.

- Basal cell cancer is rarely staged, because it doesn't usually spread to other organs. However, it may be staged if it is very large.

- Squamous cell cancer of the skin may rarely be staged in people who have a high risk of the cancer spreading.

- Melanoma is always staged.

A number of factors may be used to identify melanoma that is likely to spread and may be hard to treat, including:

- The thickness as well as how many layers of the skin the main cancer lesion has invaded

- Whether the lesions have ulcerated

- Primary lesions with small satellites

- Lymph node involvement, and the number of lymph nodes involved

- Various other factors revealed by looking at the cancer cells under a microscope

Health professionals have come up with various methods for staging cancer. This report uses the TNM staging system recommended by the American Joint Committee on Cancer.

- T = tumor. T is followed by a number (1 - 4) and a letter (a or b) to indicate tumor thickness, how "aggressive" the tumor appears under the microscope., and the presence or absence of ulceration. This is an in situ tumor, one that has not penetrated beneath the skin.

- N = node. N is followed by a number (1 - 3). If 1 node is involved, it is called N1. If 2 to 3 nodes are involved, it is called N2. If 4 or more nodes are present, it is called N3. How much cancer is present in the nodes is also important.

- M = metastasis. M is followed by a 0 (no spread) or a 1 (spread). M1 is further subdivided into a, b, or c, depending on the site of metastasis and LDH levels.

The melanoma is considered ulcerated if skin layers over the tumor appear indistinct under the microscope.

In general, the thicker the lesion and the farther the cancer has spread, the higher the stage. Survival rates decrease with increasing stage.

- The earliest melanomas, which do not penetrate beneath the surface of the skin and are known as melanoma in situ (Tis N0 M0), are highly curable and are called stage 0 or not given a stage.

- Melanomas less than 4 mm thick suggest stage I or some stage II cancers. The next step is to try to determine whether they have spread or are likely to spread to the lymph nodes.

- Melanomas that are over 4 mm thick indicate later stages. In such cases, the lymph nodes are sometimes removed in an attempt to prevent the cancer from spreading, although about 70% of these melanomas have already spread.

Specific stages are as follows:

Stage I. Cure rates are excellent with surgical removal, since they are least likely to have spread.

- Tumor has not spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs

- Stage 1A. Tumor is 1 mm or smaller, is not ulcerated, and cell division rate is less than 1 per mm2.

- Stage IB. Tumor is 1 mm or smaller and is either ulcerated, or the cell division rate is at least 1 per mm2 . Stage IB also includes tumors between 1.01 and 2 mm in size that are not ulcerated.

Stage II. Melanomas can be cured, but the success rate lags behind that of Stage I because a small number of undetected cancer cells may have spread to distant sites. In addition to surgery, other forms of therapy may be recommended.

- No evidence of tumor spread to the lymph nodes or distant organs.

- Stage IIA. Tumor is between 1.01 and 2 mm and is ulcerated, or it is 2.01 to 4 mm without ulceration.

- Stage IIB. Tumor is between 2.01 and 4 mm and is ulcerated or greater than 4 mm but is not ulcerated.

- Stage IIC. Tumor is bigger than 4 mm and is ulcerated.

Stage III. Survival rate is lower than earlier stages.

- Stage III melanoma has spread to the lymph nodes but not to distant organs.

Stage IV. Stage IV tumors have spread under the skin or to distant organs, including distant parts of the skin. Survival rates are very low.

Treatment for Melanoma

Treatment for melanoma depends on various factors, including:

- The site of the original lesion

- The stage of the cancer

- The patient's age and general health

Treatment options include:

- Surgery to remove the tumor or tumors

- Chemotherapy

- Immunotherapy

- Radiation therapy

- Symptom relief (palliative therapy)

Surgery

Surgery is the primary treatment for all stages of melanoma. Some or all of the melanoma is often removed during the first biopsy. If cancerous tissue still remains after such a biopsy, a surgeon will cut away additional tissue from the surrounding area to remove any stray cancer cells.

Surgical management of melanoma that develops in rare sites, such as the vagina, cervix and ovaries, is becoming less aggressive. Studies have shown that wide local removal is equal to radical surgery in many of these cases. Melanoma of the urethra, bladder, and ureter usually requires extensive surgery, however.

Mohs micrographic surgery is a technique used to remove very thin layers of skin, one at a time. Each layer is examined immediately under a microscope. When the layers are shown to be cancer-free, the surgery is complete.

The amount of tissue removed depends on the size, depth, and degree of invasion:

- Stage I lesions that are less than 1 mm deep require the smallest surgical cuts, usually about 1 cm off each side and downward from the original lesion.

- For melanomas that are 2 mm or thicker, a margin of 3 cm is important for reducing the risk that the cancer will return.

- Thicker lesions require wider surgical cuts.

Doctors used to remove a large area, regardless of the cancer stage. This potentially disfiguring approach has been abandoned because studies have shown that removing wider margins does not improve survival. Nevertheless, sometimes skin grafts may need to be taken from other body sites to help cover the wound.

Lymph Node Removal. If there is evidence that melanoma has spread to nearby lymph nodes but has not spread beyond them, removing those lymph nodes may reduce the chance of recurrence and help patients live longer.

Surgery for Metastatic Melanoma. In some cases, surgical removal of distant tumors may be possible. This may extend survival, since often in melanoma the cancer spreads first only to a single site, such as the lung or the brain.

Cryosurgery. Cryosurgery freezes skin tissue and destroys it. This procedure is not useful for most melanomas, but it might have some value in specific situations. For example, it may be effective for smaller melanomas in the eye, a location that is difficult to treat with traditional surgery. It may be useful to eliminate cancer cells that remain after standard surgery for lentigo maligna melanomas, an unusual form of melanoma that has a wide surface and is difficult to treat.

Recurrence rates are very high with lentigo maligna after conservative surgery. Although this cancer grows very slowly, lentigo maligna can develop into melanoma. Most of these lesions appear on the face and neck, so extensive surgery can be disfiguring. Patients should carefully discuss with their doctor having surgery to remove all diseased tissue while causing as little cosmetic harm as possible.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is often used to treat melanomas that return or spread. This type of therapy is not intended as a cure, but it can prolong life and improve its quality. Chemotherapy tends to work better than radiotherapy for advanced stage cancers and tumors.

Drugs Used. The following are some of the chemotherapy drugs used to treat melanoma. They may be used alone or in combination under specific situations.

- Methylating agents impair the ability of cancer cells to divide. Dacarbazine (DTIC) and temozolomide (Temodar) are the drugs most often used.

- Nitrosoureas, which include carmustine (BCNU) and lomustine (CCNU) are often used.

- Taxanes, such as docetaxel (Taxotere) and paclitaxel (Taxol), are showing some activity against melanoma.

- Biochemotherapy treatment regimens combine traditional chemotherapy agents, such as cisplatin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine, with biologic agents such as interferon alpha or interleukin 2. This combination may be tried for patients with large primary tumors or disease that has spread locally.

Researchers continue to investigate other chemotherapy drugs and combinations of drugs to see which ones work best.

Side Effects. Side effects occur with all chemotherapy drugs. They are more severe with higher doses and increase over the course of treatment.

Common side effects include the following:

- Anemia

- Depression

- Diarrhea

- Fatigue

- Nausea and vomiting

- Temporary hair loss

- Weight loss

Serious short- and long-term complications can also occur, and may vary depending on the specific drugs used. They include the following:

- Abnormal blood clotting (thrombocytopenia)

- Allergic reaction

- Increased chance for infection because the drugs suppress the immune system

- Liver and kidney damage

- Menstrual abnormalities and infertility in women. A natural hormone medication called a gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue, which puts women in a temporary pre-pubescent state during chemotherapy, may preserve fertility in some women.

- Severe drops in white blood cells (neutropenia). Certain chemotherapy drugs, such as taxanes, pose a higher risk for this side effect. White blood cell count may be improved by adding a drug called granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (either filgrastim or lenograstim).

- Problems in concentration, motor function, and memory, which may be long-term

- Rarely, secondary cancers such as leukemia

Treating Side Effects

Drugs known as serotonin antagonists, especially ondansetron (Zofran) can relieve nausea and vomiting in nearly all patients given moderate drugs, and in most patients who take more powerful drugs.

Benefits of Chemotherapy. About 20% of cancers shrink in response to one or more of these drugs, but the effects last only 3 - 6 months. If the tumors completely disappear, the cancer may stay in remission much longer, but in virtually all cases it returns.

Chemotherapeutic Regional Perfusion

Chemotherapeutic regional perfusion (also called isolated limb perfusion) is a technique used to give a person very high-dose chemotherapy. It is often used effectively for melanoma that returns or spreads and that occurs on the arm or leg. It does not appear to be useful for preventing cancer spread after a first occurrence of melanoma in one of these locations.

This technique involves the following:

- The blood supply to the limb with melanoma is temporarily interrupted using a tourniquet and then rechanneled through a heart-lung machine.

- Anticancer drugs are added to the blood in up to 10 times the standard doses.

- The blood is then heated to enhance the drug's potency.

- The chemo-infused blood is sent directly to the melanoma site, minimizing the likelihood of drug toxicity.

- Adverse effects occur in less than 1% of cases, and include severe problems in the treated limb (rarely leading to amputation) and drug leakage into the bloodstream. This can severely reduce white blood cells and lead to serious infection.

In addition to its use in the arms and legs, perfusion techniques have also been tested for the pelvis, head, neck, skin of the breast, and even the abdomen.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy uses drugs to boost the patient's own immune system. Immunotherapy after surgery may help prevent recurrence in certain people with melanoma. These medicines are usually given along with chemotherapy, other immunotherapies, or both.

Immunotherapy drugs being used include:

- Interferon alpha is an FDA-approved immunotherapy for stage III melanoma. Pegylated interferon alpha 2B has shown a positive effect on relapse free survival rate for stage III melanoma. Although interferon drugs have provided some benefit, their use is controversial because of significant side effects.

- Interleukin-2 (Proleukin) is a hormone-like substance that stimulates the growth of cancer-fighting white blood cells. High-dose interleukin-2 has been shown to help patients with melanoma that has spread. The drug can cause significant side effects, including very low blood pressure, heart rhythm abnormalities, severe infections, and shortness of breath. The side effects are manageable, however, and nearly always reversible.

Vaccine Immunotherapy. Vaccine immunotherapy is the use of a specific vaccine to treat an existing cancer. In this case, the vaccine targets one or more proteins that are produced by melanoma cells.

Vaccine immunotherapy requires the body to build up its own defenses. It can take months before benefits occur, but when they do, tumor reduction is more lasting than with chemotherapy. Vaccines also seem to have fewer side effects than interleukin and interferon.

Many therapeutic melanoma vaccines are in the advanced stages of testing, but none is approved for use in the United States at this time. A combination of an experimental melanoma vaccine and interleukin-2 has shown very promising results compared to interleukin-2 alone in late phase testing of patients with advanced stage III or stage IV melanoma. Patients receiving the combination treatment lived longer and their tumors stopped growing for longer periods compared to patients receiving only interleukin-2. The vaccine is only suitable for people with a particular class of immune proteins known as HLA*A0201.

Monoclonal antibodies. A recent development in the fight against melanoma is the use of the new monoclonal antibody ipilimumab (Yervoy). This antibody allows the immune cells to attack tumors more effectively by blocking a regulator gene of the immune system. In March 2011, it was approved by the FDA for use in adult patients with late stage, inoperable melanoma. This drug, however, carries with it the risk of potentially fatal side effects that include intestinal inflammation (colitis) and inflammation of the liver (hepatitis).

BRAF Inhibitors

Vemurafenib (Zelboraf) is an inhibitor of the mutated BRAF protein, which is found in approximately 50% of metastatic melanoma cases. Vemurafenib is approved by the FDA for treating metastatic or inoperable melanoma in patients with the BRAF mutation, and has proven superior to chemotherapy. A newer agent, dabrafenib, seems equally effective but with fewer skin side effects.

Radiation

In general, radiation is used to help relieve pain and discomfort caused by cancer that has spread or recurred. Radiation is not used as often for melanoma as it is for other forms of cancer because melanoma cells tend to be more resistant to its effects. It may be useful in the following cases:

- Patients unwilling or unable to have surgery.

- In some patients with tumors less than 3 cm deep, radiation may help slow down cancer spread when combined with a super-heating process using microwaves.

- In some high risk patients with melanoma that has spread to lymph nodes, surgery combined with regional radiation (adjuvant radiotherapy) may reduce the rate of reoccurrence.

- Brachytherapy, in which radioactive seeds are implanted close to the tumor, has been used with success for melanoma of the eye.

- Lentigo maligna may sometimes be treated successfully with specific radiation treatments called soft, or Grenz, x-rays.

- Radiotherapy using a gamma knife (very focused gamma radiation) is also effective for cancer that has spread to the brain. In some cases it halts the cancer growth and, in rare situations, even eliminates it.

Palliative Therapy

The goal of palliative therapy is to improve the patient's quality of life and relieve symptoms. It is not a cure. Advanced melanoma that has spread to distant sites often cannot be cured, although surgery to remove tumors that have spread may provide some benefit by easing pain, increasing the general quality of life, and lengthening survival.

Patients should ask their doctors about clinical trials, studies that examine new immunotherapies (vaccines, cytokines), gene therapies, chemotherapy combinations, or other treatments.

Treatment for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer

Many options are available for treating nonmelanoma skin cancer, including:

- Surgery

- Cryosurgery

- Photodynamic therapy

- Radiation

- Topical 5-fluorouracil

- Topical immunotherapy with imiquimod

Most basal and squamous cell cancers are treated with surgery or radiation. Research has found that surgery has the best results, but because it can have cosmetic effects, many patients opt for radiation.

The first step in nonmelanoma skin cancers is to determine the risk of aggressive types of these tumors. Basal cell tumors are considered high-risk.

Squamous cell cancers of the skin are considered to be high-risk if any of the following are present:

- Recurrence at the same place where there was a previously treated squamous cell tumor

- Poorly defined borders

- Spread to the lymph nodes

- Occurrence in a patient with a suppressed immune system

- Certain features seen in microscopic examination

Surgery

For any skin cancer and for some keratoses that need to be removed, surgery is the first treatment. One of the following surgeries is usually used:

Excisional Surgery. Cutting out the tumor and then assessing the tumor borders (margins).

Curettage and Electrodesiccation. This procedure involves scraping away the cancerous tissue, followed by electric cauterization to stop the bleeding.

Mohs Micrographic Surgery. Mohs surgery is a procedure used for skin cancers at high risk for returning or becoming invasive. The technique removes very thin layers of skin one at a time. Each layer is examined immediately under a microscope. When the layers are shown to be cancer-free, the surgery is complete.

Good candidates for Mohs surgery include:

- People with basal cell cancer greater than 1 cm (about half an inch)

- People with basal cell cancer on the face, ear, or neck

- People with basosquamous carcinoma (a specific type of basal cell cancer)

- Young people with skin cancer

Mohs surgery saves more healthy tissue than other procedures and is highly effective. It results in a 99% cure rate for primary tumors and a 95% cure rate for cancers that return. It can be safely performed in the doctor's office. Complications are uncommon but can include bleeding and infection.

Lasers. Laser surgery may be useful for certain basal cells and for keratoses that appear on the lips, although it is not clear whether lasers offer any advantages over other surgical treatments. Lasers do not appear to be very effective for thick or tough squamous cell cancers.

Cryosurgery

Cryosurgery removes skin cancer cells or actinic keratoses by freezing the affected tissue with liquid nitrogen. Studies have shown that cryosurgery can be used to remove even wide areas of actinic keratoses, and that it may be more successful over the long term than treatment with 5-fluorouracil, the standard drug. Cryosurgery also appears to reduce the risk for squamous cell cancer in these patients.

Cryotherapy achieves good cosmetic results for many patients. However, it may cause blistering and ulceration, leading to pain and infection, as well as harmless, but undesirable, skin-color changes.

The disadvantage of cryosurgery is that no tissue is taken to examine under a microscope to show that the cancer was completely removed.

Radiation

In unusual cases where the skin cancer may be in an inoperable position (such as the eyelid or the tip of the nose) or if cancer has come back multiple times, radiation therapy may be indicated. Radiation therapy is more often used in the elderly.

Radiation is directed at the tumor. It may take 1 - 4 weeks, with treatments done several times a week. One technique being investigated for basal and squamous cell cancer uses radiation implants (brachytherapy) and custom-made molds to specifically target the radiation to the cancer site. Studies suggest that this treatment is very effective with few complications.

Topical Phototherapy and Aminolevulinic Acid (ALA)

Topical phototherapy with the drug aminolevulinic acid (ALA) is a nonsurgical method that is proving to be a good choice for treating actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers. The technique involves shining blue light onto the cancer area after the patient has taken ALA. ALA accumulates in the skin cells. When the cells are exposed to intense light, the chemical causes them to die. This approach allows precise targeting of one or more lesions, leaving healthy skin unaffected.

Topical phototherapy with ALA does not penetrate deeper than the epidermis (the top layer of the skin), so it does not produce scarring or changes in skin color, as cryotherapy or other more invasive treatments do. However, it can cause pain and irritation, including stinging, itching, and burning.

ALA Phototherapy for Actinic Keratoses. Phototherapy works best on flat lesions when it is performed in two treatments, and is more effective for clearing lesions on the face than those on the scalp. Phototherapy can also treat multiple lesions at the same time instead of one after another, as in cryotherapy. Studies suggest that it may work as well as cryotherapy and achieve better cosmetic results (more patients report burning and itching with phototherapy, however). Phototherapy is also equal to topical 5-fluorouracil in effectiveness and achieving a satisfactory appearance.

ALA Phototherapy for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancers. In patients with squamous cell cancer in situ, Bowen disease, and superficial basal cell cancer, phototherapy has been equal to cryotherapy, with better healing and appearance afterward.

Some studies have shown that about 10% of patients using phototherapy have a recurrence within 1 year. These recurrence rates are higher than with surgery and other standard treatments. Longer-term studies are required before ALA phototherapy can be recommended for most patients with nonmelanoma skin cancers.

Medications

Several medications are being used for keratoses and some may be helpful for skin cancers as well. Besides cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil is the other most commonly used treatment for actinic keratoses. Other medications are also available.

Medications for Keratoses and Common Skin Cancers | |||||

| Medication | Skin Conditions Affected | Oral or Topical | Comments | ||

5-Fluorouracil | Actinic keratoses, Bowen's disease and small nonmelanoma skin cancers. | Topical cream (Efudex, Fluoroplex) or injected gel containing 5-FU and epinephrine (AccuSite). | 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) removes actinic keratoses and is useful for some patients with a large number of lesions. It requires twice daily application for 3 - 4 weeks. It can cause significant redness, irritation, swelling, and crusting, which takes 2 - 4 weeks to heal. Newer preparations are reducing these side effects. It is still unclear whether this medication protects against recurrent keratoses or future skin cancer. Of concern is the possibility that 5-FU will clear the top of a skin cancer and obscure the rest of the cancer that lies beneath the surface of the skin. | ||

Diclofenac and hyaluronan (Solaraze) | Actinic keratoses (approved). Investigated for basal cell. | Topical gel applied twice a day. | Diclofenac is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). When used to treat actinic keratoses, it is delivered to the skin with hyaluronan, a water-seeking molecule that helps maintain skin tension. It has modest effects and when healing occurs, it may not be evident for at least a month after treatment ends. However, it causes less irritation than 5-FU and may be useful for some people. Sun avoidance is necessary during treatment. | ||

Imiquimod (Aldara) | FDA approved for the treatment of superficial basal cell cancer and actinic keratoses. Investigated for Bowen's disease and squamous cell cancer. | Imiquimod is a topical cream. Frequency and duration of application continues to be studied. Applied 2 times per week for 16 weeks for AK. | Imiquimod triggers the production of immune factors that help fight cell proliferation. It should be used only when surgery for basal cell cancer is inappropriate. | ||

| Alpha-Interferons | Basal cell cancer | Require injections administered three times a week. | Interferons are immune factors that are being used to treat a number of serious conditions. Alpha-interferon injections may be effective against skin cancers that are hard to treat using conventional surgical measures. Cosmetic results are reported by 83% of patients to be good or very good. | ||

Prognosis

Virtually all basal and squamous type skin cancers can be cured if treated early. These cancers are more likely to recur if they develop on the head and neck area, or if they are thicker. Most of the time, the recurrence will be local (at the same location as the original tumor).

The outlook for melanoma depends on when it is diagnosed and where it forms on the body.

Certain factors indicate melanoma is more likely to have spread or return after treatment:

- Tumor thickness, usually measured in millimeters. A thicker tumor indicates the tumor is more likely to have spread

- Presence of ulceration of the skin of the primary tumor location

- Melanomas found on the head or neck area

- Melanoma that has spread at the time of first diagnosis.

In general, after patients are treated for melanoma, the longer they go without the cancer returning after treatment, the better their chance of remaining disease-free. However, relapses are not uncommon in those whose first melanoma was larger.

Anyone who has recovered from melanoma should carefully follow preventive guidelines and remain vigilant for suspicious lesions, because the risk for developing a new melanoma is increased even if the first one was successfully cured. Such relapses may occur even years after the original diagnosis.

Resources

- www.aad.org -- American Academy of Dermatology

- www.cancer.org -- American Cancer Society

- www.asds.net -- American Society for Dermatologic Surgery

- www.melanoma.org -- Melanoma Patients' Information Page

- www.cancer.gov -- National Cancer Institute

- www.nccn.org -- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- www.skincancer.org -- The Skin Cancer Foundation

- www.epa.gov/sunwise/uvindex.html -- UV index information

References

Abbasi NR, Yancovitz M, Gutkowicz-Krusin D, Panageas K, Googe P, King R, et al. Utility of lesion diameter in the clinical diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:469-474.

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts and Figures 2011. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; 2011.

Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S-j, et al. Final Version of 2009 AJCC Melanoma Staging and Classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206

Basal cell and squamous cell cancers: NCCN Medical Practice Guidelines and Oncology;V.2. 2012. Available online.

Brantsch KD, Meisner C, Schonfisch B, Trilling B, Wehner-Caroli J, Rocken M, et al. Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:713-720.

Bristol-Myers Squibb. Yervoy web site. Available online. Last accessed July 3, 2011.

Chapman PB. Updated overall survival (OS) results for BRIM-3, a phase III randomized, open-label, multicenter trial comparing BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib (vem) with dacarbazine (DTIC) in previously untreated patients with BRAFV600E-mutated melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(suppl; abstr 8502^)

Clinical practice guideline for melanoma: NCCN Medical Practice Guidelines and Oncology; V.1.2013. Available online.

Cyr PR. Atypical Moles. Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(6):735-40. Review.

Eggermont AM, Suciu S, Santinami M, et al: EORTC Melanoma Group. Adjuvant therapy with pegylated interferon alfa-2b versus observation alone in resected stage III melanoma: final result of EORTC 18991, a randomised phase III trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):117-26.

Flaherty KT, Robert C, Hersey P, et al. Improved Survival with MEK Inhibition in BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367:107-114.

Fayter D, Corbett M, Heirs M, Fox D, Eastwood A. A systematic review of photodynamic therapy in the treatment of pre-cancerous skin conditions, Barrett's oesophagus and cancers of the biliary tract, brain, head and neck, lung, oesophagus and skin. Health Technol Assess. 2010;14(37):1-288.

Garcia C, Polette E, Crowson AN. Basosquamous carcinoma. J Am Dermatol. 2009;60(1):137-43.

Genentech USA, Inc. Zelboraf Prescribing Information. Available online.

Gershenwald JE, Ross MI. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy for cutaneous melanoma. NEngl J Med. 2011;364(18):1738-1745.

Goodson AG, Grossman D. Strategies for early melanoma detection: Approaches to the patient with nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60(5):719-35: quiz 736-8. Review.

Guadagnolo BA, Zagars GK. Adjuvant radiation therapy for high-risk notal metastases from cutaneous melanoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(4):409-16.

Hauschild A, Grob J-J, Demidov L. et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2012; 380(9839): 358 - 365.

Hodi FS, McDermott DF. Improved Survival with Ipilimumab in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma. N Eng J Med. ePub June 5, 2010. Available online.

Kirby JS, Miller CJ. Intralesional chemotherapy for nonmelanoma skin cancer: a practical review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63(4):689-702.

Lansbury L, Leonardi-Bee J, Perkins W, Goodacre T, Tweed JA, Bath-Hextall FJ. Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. CochraneDatabase Syst Rev. 2010;(4):CD007869.

Lange JR, Fecher LA, Sharfman WH, et al. Melanoma. In: Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Nierderhuber JE, Kastan MB, McKenna WG, eds. Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Churchill Livingstone; 2008:chap 73.

Lazovich D, Vogel RI, Berwick M, Weinstock MA, Anderson KE, Warshaw EM. Indoor tanning and risk of melanoma: a case-control study in a highly exposed population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(6):1557-1568.

Love WE, Bernhard JD, Bordeaux JS. Topical imiquimod or fluorouracil therapy for basal and squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(12):1431-1438.