Parkinson's disease

Highlights

What Is Parkinson’s Disease?

Parkinson’s disease is a neurological disorder that affects movement, muscle control, and balance. Parkinson’s disease most commonly affects people 55 - 75 years old, but it can also develop in younger people. The disease is usually progressive, with symptoms becoming more severe over time.

Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease

Parkinson’s disease may be difficult to diagnose in its early stages. The disease is diagnosed mostly through symptoms, which may include:

- Tremors (shaking) in the hands, arms, legs, and face

- Slowness of movement, especially when initiating motion

- Muscle rigidity

- Difficulty with walking, balance, and coordination

- Difficulty eating and swallowing

- Digestive problems

- Speech problems

- Depression and difficulties with memory and thought processes

Treatment

There is no cure for Parkinson’s disease. Treatments focus on controlling symptoms and improving quality of life.

- Medications. Because Parkinson’s disease symptoms are due to a deficiency of the brain chemical dopamine, the main drug treatments help increase dopamine levels in the brain. Levadopa, usually combined with carbidopa, is the standard drug treatment. For patients who do not respond to levadopa, dopamine agonists (drugs that mimic the action of dopamine) may be prescribed. Other types of medication may also be used. Unfortunately, many of these drugs can cause side effects and lose effectiveness over time.

- Physical Therapy. Physical therapy is an important part of Parkinson’s treatment. Rehabilitation can help patients improve their balance, mobility, speech, and functional abilities.

- Surgery. In some cases of advanced-stage Parkinson’s disease, surgery may help to control motor problems. Deep brain stimulation is currently the preferred surgical method.

New Drug Approval

In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved rotigotine (Neupro) for treatment of early and advanced stage Parkinson’s disease. The dopamine agonist drug is delivered through a transdermal (skin) patch that is applied once a day.

Deep Brain Stimulation: Expert Consensus

In 2011, a panel of 50 international experts published a consensus statement on the use of deep brain stimulation (DBS). The panel advised that:

- It is most appropriate to consider DBS for younger patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease who do not have significant cognitive or psychiatric problems.

- Deep brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus (STN) or globus pallidus pars interna (GPI) works equally well in improving motor symptoms and STN treatment may help patients use less medication. However, DBS of the STN can result in worsening of non-motor symptoms, including depression, apathy, and falls.

- DBS is also effective in controlling tremors and dyskinesia.

- This procedure should be performed by an experienced neurosurgeon working as part of a multidisciplinary team.

Tai Chi May Improve Balance

Tai chi, a Chinese martial art that emphasizes slow flowing motions and gentle movements, may help patients with Parkinson’s improve strength and balance and reduce the risk of falls, according to a small study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Other small studies have suggested that dance styles such as the Argentinean tango may help with balance and mobility.

Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is a slowly progressive neurological disorder that affects movement, muscle control, and balance. Parkinson’s disease is part of a group of conditions called motor system disorders, which are associated with the loss of dopamine-producing brain cells. These dopamine-associated motor disorders are referred to as parkinsonisms.

Parkinson's Disease and Dopamine Loss

Parkinson's disease occurs from the following process in the brain:

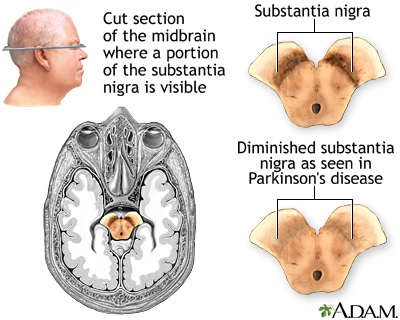

- PD develops as cells are destroyed in certain parts of the brain stem, particularly the crescent-shaped cell mass known as the substantia nigra.

- Nerve cells in the substantia nigra send out fibers to the corpus stratia, gray and white bands of tissue located in both sides of the brain.

- There the cells release dopamine, an essential neurotransmitter (a chemical messenger in the brain). Loss of dopamine in the corpus stratia is the primary defect in Parkinson's disease.

Dopamine deficiency is the hallmark feature in PD. Dopamine is one of three major neurotransmitters known as catecholamines, which help the body respond to stress and prepare it for the fight-or-flight response. Loss of dopamine negatively affects the nerves and muscles controlling movement and coordination, resulting in the major symptoms characteristic of Parkinson's disease. Dopamine also appears to be important for efficient information processing, and deficiencies may also be responsible for the problems in memory and concentration that occur in many patients.

Causes

Although doctors don’t know exactly what causes Parkinson's disease, they think it’s probably due to a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

Genetic Factors

Specific genetic factors appear to play a strong role in early-onset Parkinson's disease, an uncommon form of the disease. Multiple genetic factors may also be involved in some cases of late-onset Parkinson's disease.

Environmental Factors

Environmental factors are probably not a sole cause of Parkinson's disease, but they may trigger the condition in people who are genetically susceptible.

Some evidence implicates pesticides and herbicides as possible factors in some cases of Parkinson's disease. A higher incidence of parkinsonism has long been observed in people who live in rural areas, particularly those who drink private well water or are agricultural workers.

Risk Factors

Age

The average age of onset of Parkinson's disease is 55. About 10% of Parkinson's cases are in people younger than 40 years old. Older adults are at higher risk for both parkinsonism and Parkinson's disease.

Gender

Parkinson’s disease is more common in men than in women.

Family History

People with siblings or parents who developed Parkinson's at a younger age face an increased risk for the condition. However, relatives of patients who developed Parkinson’s at an older age appear to have an average risk.

Race and Ethnicity

African-Americans and Asian Americans appear to have a lower risk than caucasians.

Possible Protective Factors

Both smoking and coffee drinking are associated with a lower risk for PD.

Smoking and Nicotine. Cigarette smokers appear to have a lower risk for Parkinson's disease, indicating possible protection by nicotine. This finding is, of course, no excuse to smoke. The few studies on nicotine replacement as a treatment for Parkinson’s have not provided any strong evidence that nicotine therapy provides benefits.

Coffee Consumption. Some studies suggest that the risk for PD in coffee drinkers is lower than for non-coffee drinkers. In a 30-year study of Japanese-American men, coffee consumption was associated with a lower risk for Parkinson's disease, and the more coffee they drank, the lower their risk became.

Complications

Parkinson's disease (PD) is not fatal, but it can reduce longevity. The disease progresses more quickly in older patients, and may lead to severe incapacity within 10 - 20 years. Older patients also tend to have muscle freezing and greater declines in mental function and daily functioning than younger people. If PD starts without signs of tremor, it is likely to be more severe than if tremor had been present.

Parkinson's disease can seriously impair the quality of life in any age group. In addition to motor symptoms (motion difficulties, tremors) Parkinson’s can cause various non-motor problems that have physical and emotional impacts on patients and their families.

Swallowing Problems

Swallowing problems (dysphagia) are sometimes associated with shorter survival time. Loss of muscle control in the throat not only impairs chewing and swallowing, which can lead to malnourishment, but also poses a risk for aspiration pneumonia.

Emotional and Behavioral Problems

Depression is very common in patients with Parkinson's. The disease process itself causes changes in chemicals in the brain that affect mood and well-being. Anxiety is also very common and may present along with depression.

Some drug treatments (levodopa combined with a dopamine agonist) can cause compulsive behavior, such as gambling, shopping, and increased sexuality. Patients who have pre-existing tendencies for novelty-seeking behavior, or a family or personal history of alcohol abuse, may be more likely to develop compulsive gambling. Deep brain stimulus (DBS) surgery may also increase the risk for compulsive gambling in patients who have a history of gambling.

Cognitive and Memory Problems

Impaired Thinking (Cognitive Impairment). Defects in thinking, language, and problem solving skills may occur early on or later in the course of the disease. These problems can occur from the disease process or from side effects of medications used to treat Parkinson’s. Patients with PD are slower in detecting associations, although (unlike in Alzheimer's disease) once they discover them they are able to apply this knowledge to other concepts.

Dementia. Dementia occurs in about two-thirds of patients with Parkinson’s, especially in those who developed Parkinson’s after age 60. Dementia is significant loss of cognitive functions such as memory, judgment, attention, and abstract thinking. It is most likely to occur in older patients who have had major depression. PD marked by muscle rigidity (akinesia), rather than tremor, and early hallucinations also increase the risk for dementia. (Visual hallucinations can also occur as a side effect of dopamine medication.) Unlike Alzheimer's, language is not usually affected in Parkinson's-related dementia.

Sleep Disorder

Excessive daytime sleepiness, insomnia, and other sleep disorders are common in PD, both from the disease itself and the drugs that treat it. Bladder problems can also contribute to sleep disturbances. Many patients also suffer from nighttime leg cramps and restless legs syndrome. Some of the medications used for Parkinson's may cause vivid dreams as well as waking hallucinations.

Sexual Dysfunction

Although Parkinson's disease and its treatments can cause compulsive sexual behavior, the disease can also cause a loss of sexual desire in both men and women. For men, erectile dysfunction can be a complication of Parkinson’s.

Bowel and Bladder Complications

Constipation is a common complication of Parkinson’s disease. It is often caused by muscle weakness that can slow down the action of the digestive system. Weakness in pelvic floor muscles can also make it difficult to defecate.

Patients with Parkinson’s disease frequently experience urinary incontinence, including increased urge and frequency. Parkinson’s can also cause urinary retention (incomplete emptying of the bladder).

Sensory Problems

Decreased Sense of Smell. Many patients experience an impaired sense of smell.

Vision Problems. Vision may be affected, including impaired color perception and contrast sensitivity.

Pain. Painful symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease include muscle numbness, tingling, and aching. Pain in Parkinson’s is often a result of dystonia, involuntary muscle contractions and spasms that can cause twisting and jerking.

Symptoms

Tremors

Parkinson's disease (PD) symptoms often start with tremor, which may occur in the following ways:

- Tremors may be only occasional at first, starting in one finger and spreading over time to involve the whole arm. The tremor is often rhythmic, 4 - 5 cycles per second, and frequently causes an action of the thumb and fingers known as pill rolling.

- Tremors can occur when the limb is at rest or when it is held up in a stiff unsupported position. They usually disappear briefly during movement and do not occur during sleep.

- Tremors can also eventually occur in the head, lips, tongue, and feet. Symptoms can occur on one or both sides of the body.

About a quarter of patients with Parkinson’s do not develop tremor.

Motion and Motor Impairment

Many PD symptoms involve motor impairment caused by problems in the brain nerves that regulate movement:

- Slowness of motion, particularly when initiating any movement (a condition called akinesia or bradykinesia), is one of the classic symptoms of Parkinson's disease.

- Patients may eventually develop a stooped posture and a slow, shuffling walk. The gait can be erratic and unsteady. After several years, muscles may freeze up or stall, usually when a patient is making a turn or passing through narrow spaces, such as a doorway. Patients' posture can be unstable, and they have an increased risk for falls.

- Intestinal motility (the ability to swallow, digest, and eliminate) may slow down, causing eating problems and constipation.

- Muscles may become rigid. This symptom often begins in the legs and neck. Muscle rigidity in the face can produce a mask-like, staring appearance.

- Motor abnormalities that limit action in the hand may develop in late stages. Handwriting, for instance, often becomes small.

- Normally spontaneous muscle movements, such as blinking, may need to be done consciously.

- Patients may develop speech problems, including soft voice or slurred speech.

Other Symptoms of Parkinson's Disease

Parkinson’s disease also causes non-motor symptoms, including sleep problems, gastrointestinal and urinary disorders, sexual dysfunction, decreased sense of smell, and depression and anxiety. [See Complications section of this report.]

Sialorrhea (drooling) is a common and bothersome symptom for those with Parkinson's disease. It can cause chapped skin and lips around the mouth, dehydration, an unpleasant odor, and social embarrassment.

Diagnosis

Parkinson’s disease can be difficult to diagnose in its early stages. Doctors base their diagnosis on the patient’s medical history and symptoms evaluated during a neurological exam. No laboratory or imaging tests can diagnose Parkinson’s, although brain scans such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron-emission tomographic (PET) may be used to rule out other neurological disorders.

Medical History

A medical and personal history should include any relevant symptoms as well as any medications taken, and information on other conditions the patient may have.

Neurological Exam

In a neurological exam, the doctor will ask the patient to sit, stand, walk, and extend their arms. The doctor will observe the patient’s balance and coordination. Parkinson's may be suspected in patients who have at least two of the following four symptoms, especially if they are more obvious on one side of the body:

- Tremor (shaking) when the limb is at rest

- Slowness of movement (bradykinesia)

- Rigidity, stiffness, or increased resistance to movement in the limbs or torso

- Poor balance (postural instability)

Drug Challenge Test

A levodopa challenge test may confirm a diagnosis of Parkinson's disease. If patients' symptoms improve when they take levodopa, they likely have Parkinson's, ruling out other neurological diseases.

Tests for Depression and Dementia

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends the Beck Depression Inventory or the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale to screen for depression in patients with Parkinson's disease. The AAN recommends the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Cambridge Cognitive Examination (CAMCOG) tests to screen for dementia. During these tests, the patient answers a series of questions.

Ruling out Conditions that Mimic Parkinson's Disease

Parkinsonism Plus Syndromes. Parkinson’s disease is the most common type of parkinsonism. Parkinsonism refers to a group of movement disorders that share similar symptoms with Parkinson’s disease, but also have unique symptoms of their own. About 15% of parkinsonism cases are due to conditions called Parkinson’s plus syndromes (PPS) or atypical parkinsonism. These syndromes include:

- Corticobasal degeneration. Marked by apraxia (inability to perform coordinated movements or use familiar objects), stiffness that is more severe than typical Parkinson’s disease, and twitching or jerking in the hand.

- Lewy body dementia. One of the most common types of progressive dementia. Symptoms include visual hallucinations and loss of spontaneous movement.

- Multiple system atrophy. Symptoms include fainting, constipation, erectile dysfunction, urinary retention, and loss of muscle coordination.

- Progressive supranuclear palsy. Marked by frequent falls, personality changes, and difficulty focusing the eyes.

Patients with PPS often have earlier and more severe dementia than those with Parkinson’s disease. In addition, they do not usually respond to medications that are used to treat Parkinson’s disease.

Other Neurologic Conditions. Many medical conditions may cause some symptoms of Parkinson's disease and parkinsonism. Hardening of the arteries (arteriosclerosis) in the brain can cause multiple small strokes, which can produce loss of motor control. Alzheimer’s disease can share similar symptoms with Parkinson’s and the conditions can exist together.

Medications. Several drugs, including antipsychotic and antiseizure medications, can cause Parkinson’s symptoms.

Treatment

There is no cure for Parkinson’s disease, but drugs, physical therapy, and surgical interventions can help control symptoms and improve quality of life. The goals of treatment for Parkinson's disease are to:

- Relieve disabilities

- Balance the problems of the disease with the side effects of the medications

Treatment is very individualized for this complicated condition. Patients must work closely with doctors and therapists throughout the course of the disease to customize a program suitable for their particular and changing needs. Patients should never change their medications without consulting their doctor, and they should never stop taking their medications abruptly.

No treatment method has been proven to change the course of the disease. For early disease with little or no impairment, drug therapy may not be necessary.

A number of issues must be considered in choosing medication treatment. These include how effective a specific drug group is in treating symptoms, side effect profile, loss of effectiveness over time, and other considerations.

Treatments for Onset of Parkinson's Disease

The American Academy of Neurology recommends the following therapies for the initial treatment of Parkinson’s disease:

Levodopa (L-dopa). Levodopa, or L-dopa, has been used for years and is the gold standard for treating Parkinson's disease. L-dopa increases brain levels of dopamine. It is probably the most effective drug for controlling symptoms and is used in nearly all phases of the disease. The standard preparations (Sinemet, Atamet) combine levodopa with carbidopa, a drug that slows the breakdown of levodopa. Levodopa is better at improving motor problems than dopamine agonists but increases the risk of involuntary movements (dyskinesia). Effectiveness tends to decrease after 4 - 5 years of usage.

Dopamine Agonists. Dopamine agonist drugs mimic dopamine to stimulate the dopamine system in the brain. These drugs include pramipexole (Mirapex, generic), ropinirole (Requip, generic), bromocriptine (Parlodel, generic), and rotigotine (Neupro).

Selegiline (Eldepryl) and Rasagiline (Azilect). Selegiline (Eldepryl, generic) is a monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitor that may have some mild benefit as an initial therapy. Rasagiline (Azilect) is another MAO-B inhibitor used for treatment of Parkinson’s.

Treatments for Off Time

Drug treatments for Parkinson disease do not consistently control symptoms. At certain points during the day, the beneficial effects of drugs wear off, and symptoms can return, including uncontrolled muscular motor function, difficulty walking, and loss of energy. The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends the following drugs as best for controlling off time symptoms:

- Entacapone (Comtan) belongs to a class of drugs called catechol-o-methyl transferase (COMT) inhibitors. COMT inhibitors help prolong the effects of levodopa by blocking an enzyme that breaks down dopamine.

- Rasagiline (Azilect) belongs to a class of drugs called monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors. These drugs slow the breakdown of dopamine that occurs naturally in the brain and dopamine produced from levodopa.

Other dopamine agonists, such as ropinirole (Requip, generic) and pramipexole (Mirapex, generic), and the COMT inhibitor tolcapone (Tasmar) may also be helpful for treating off-time symptoms. Deep brain stimulation is a surgical treatment that may help improve motor fluctuations in some patients.

Treatments for Other Symptoms of Parkinson's

Conditions associated with non-motor impairment symptoms of Parkinson's disease may need a variety of treatments.

Depression. Antidepressants used for PD include tricyclics, particularly amitriptyline (Elavil). Some studies have found that selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) -- which include fluoxetine (Prozac, generic), sertraline (Zoloft, generic), and paroxetine (Paxil, generic) -- may worsen symptoms of Parkinson's. Doctors should monitor patients taking SSRIs.

Psychotic Side Effects. Studies indicate that clozapine (Clozaril, generic) and quetiapine (Seroquel), antipsychotic drugs used to treat schizophrenia, may be the best drugs for treating psychosis in patients with Parkinson's disease. A similar drug, olanzapine (Zyprexa), should not be used for patients with PD because it can worsen psychotic symptoms.

Dementia. The cholinesterase inhibitor drugs donepezil (Aricept) and rivastigmine (Exelon) are used to treat Alzheimer’s disease and are sometimes used for Parkinson’s. The benefit from these drugs is often small, and patients and their families may not notice much change.

Daytime Sleepiness and Fatigue. Modafinil (Provigil), a drug used to treat narcolepsy may be helpful for patients with sleepiness related to their disease. Methylphenidate (Ritalin, generic) may be considered for patients who experience fatigue.

Erectile Dysfunction. PDE5 inhibitor drugs such as sildenafil (Viagra), tadalafil (Cialis), and vardenafil (Levitra) can be helpful for men with Parkinson's disease who suffer from erectile dysfunction. However, these drugs may worsen orthostatic hypotension (lightheadedness or dizziness that occurs when suddenly standing up), a side effect of some PD medications.

Constipation. Laxatives that contain macrogol (polyethylene glycol) may be helpful for improving constipation. Brand names include Softlax, Miralax, and Glycoprep.

Drooling. Glycopyrrolate, scopolamine, and injections of botulinum toxin may be used to relieve drooling symptoms.

Treating Advanced Disease

Advanced Parkinson’s disease poses challenges for both patients and caregivers. Eventually, symptoms such as stooped posture, freezing, and speech difficulties may no longer respond to drug treatment. Surgery (deep brain stimulation) may be considered for some patients. Patients become increasingly dependent on others for care and require assistance with daily tasks. Modifications (wheelchair ramps, grab bars and handrails) may need to be made in the home. Some patients may need to move to an assisted living facility or nursing home. The goal of treatment for advanced Parkinson’s disease should be on providing patients with safety, comfort, and quality of life.

Levadopa (L-dopa)

Levodopa, also called L-dopa, which is converted to dopamine in the brain, remains the gold standard for treating Parkinson's disease. The standard preparations (Sinemet, Atamet) combine levodopa with carbidopa, which improves the action of levodopa and reduces some of its side effects, particularly nausea. Dosages vary, although the preparation is usually taken in three or four divided doses per day.

Indications of Early Treatment Success or Failures

In general L-dopa has the following effects on Parkinson's disease:

- It is most effective against rigidity and slowness.

- It produces less benefit for tremor, balance, and gait.

In many patients, levodopa significantly improves the quality of life for many years.

Side Effects

The toxic effects of levodopa with or without carbidopa are considerable.

Physical Side Effects. The physical side effects include:

- Dyskinesia. Dyskinesia (the inability to control muscles) is a very distressing side effect of levodopa. Dyskinesia can take many forms, most often uncontrolled flailing of the arms and legs or chorea, rapid and repetitive motions that can affect the limbs, face, tongue, mouth, and neck.

- Low blood pressure (hypotension). Low blood pressure is a common problem during the first few weeks, particularly if the initial dose is too high.

- Arrhythmia. In some cases the drug may cause abnormal heart rhythms.

- Gastrointestinal effects. Stomach and intestinal side effects are common even with carbidopa. Taking the drug with food can alleviate the nausea. However, proteins interfere with intestinal absorption of levodopa, and some doctors recommend not eating any protein until nighttime in order to avoid this interference. The drug can also cause gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Effects in the lung. Levodopa can cause disturbances in breathing function, although it may benefit patients who have upper airway obstruction.

- Hair loss.

Psychiatric and Mental Side Effects. The major adverse effects of the drug are psychiatric. Patients taking levodopa, especially in combination with other drugs, can experience:

- Confusion

- Extreme emotional states, particularly anxiety

- Vivid dreams

- Visual and possibly auditory hallucinations. The drug may even unmask dementia that had not been previously noticed.

- Effects on learning. L-dopa appears to have mixed effects on learning. It may improve working memory. However, some evidence suggests that it impairs areas of the brain related to other learning functions and social behavior.

- Sleepiness and sleep attacks

Levodopa causes fewer psychiatric side effects than other drugs used for Parkinson's disease, including anticholinergics, selegiline, amantadine, and dopamine agonists. Psychiatric side effects often occur at night. If these side effects are severe, some doctors recommend reducing or stopping the evening dose.

The Wearing-Off Effect and Dyskinesia (Inability to Control Muscles)

Within 4 - 6 years of treatment with levodopa, the effects of the drug in many patients begin to last for shorter periods of time after a dose (called the wearing-off effect), and the following pattern may occur:

- Patients may first notice slowness (bradykinesia) or tremor in the morning before the next dose is due.

- Less commonly, some experience painful dystonia, muscle spasms that can cause sustained contortions of various parts of the body, particularly the neck, jaw, trunk, and eyes and possibly the feet.

- Patients must increase the frequency or the dose of levodopa. This puts them at risk for dyskinesia (the inability to control muscles), which usually occurs when the drug level peaks.

- In some people, L-dopa eventually becomes effective only for 1 - 2 hours, and patients start to have motor fluctuations. The fluctuations may become extreme, a phenomenon known as the on-off effect, which consists of unpredictable, alternating periods of dyskinesia and immobility. Sometimes the symptoms switch back in forth within minutes or even seconds. (The transition may follow such symptoms as intense anxiety, sweating, and rapid heartbeats.)

Preventing the Wearing-Off Effect. To reduce the effects of fluctuation and the wearing-off effect, it is important to maintain as consistent a level of dopamine as possible. Unfortunately, levodopa is poorly absorbed and may remain in the stomach a long time. A number of strategies are used to take care of these problems:

- Some patients take multiple small doses on an empty stomach, crushing the pills and mixing them with a lot of liquid.

- A liquid form of Sinemet may produce fewer fluctuations and a prolonged "on" time compared with the tablet.

- A prolonged release version of levodopa and carbidopa (Sinemet CR) may control fluctuations for some patients.

Other Medications

Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B) Inhibitors

Selegiline (Eldepryl, Zelapar, generic), also known as deprenyl, is an antioxidant drug that blocks monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), an enzyme that degrades dopamine. Until recently, selegiline was commonly used in early-onset disease and in combination with levodopa for maintenance. Concerns over significant side effects have been raised, however.

A newer MAO-B inhibitor, rasagiline (Azilect), is used alone during early-stage PD and in combination with L-dopa for moderate-to-advanced PD. Unlike selegiline, which is taken twice a day, rasagiline is taken once a day.

Side Effects. MAO-B inhibitors may have severe side effects:

- Orthostatic hypotension, particularly for people taking Sinemet plus selegiline. This condition is a sudden drop in blood pressure that causes dizziness and lightheadedness when a patient stands up. Orthostatic hypotension can also occur with other Parkinson's drugs.

- High blood pressure (hypertension) if combined with drugs that increase serotonin levels -- such drugs include many antidepressants. Patients suffering from depression and taking selegiline should discuss all treatment options with their doctor.

- Dangerous increase in blood pressure if patients eat foods rich in the amino acid tyramine. While taking selegiline or rasagiline, and for 2 weeks after stopping medication, patients should avoid foods such as aged cheeses, processed lunch meats, pickled herring, yeast extract, aged red wines, draft beers, sauerkraut, and soy sauce.

- Irregular or abnormal heart rate or rhythm (cardiac arrhythmia). Selegine should be used with caution in patients with certain preexisting heart conditions.

Dopamine Agonists

Dopamine agonists stimulate dopamine receptors in the substantia nigra, the part of the brain in which Parkinson's is thought to originate. Dopamine agonists are effective in delaying motor complications during the first 1 or 2 years of treatment.

Newer Dopamine Agonists. The most commonly prescribed dopamine agonists are pramipexole (Mirapex, generic) and ropinirole (Requip, generic). They are used either alone or in combination with L-dopa. Pramipexole appears to work better and have fewer side effects than ropinirole.

Research indicates that L-dopa is better at improving motor disability, and dopamine agonists are better at reducing motor complications. L-dopa has a higher risk for dyskinesia side effects than dopamine agonists, but dyskinesia (difficulty controlling muscle movements) can also occur with dopamine agonists. There is debate about the value of dopamine agonists as initial therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Recent research suggests that early treatment with dopamine agonists may not provide any long-term advantages compared with starting treatment with L-dopa.

Side Effects. Side effects of pramipexole and ropinirole vary but can be severe and include:

- Gastrointestinal side effects (nausea and constipation). Nausea can be controlled by drugs, such as domperidone.

- Headache

- Orthostatic hypotension (sudden drop in blood pressure upon standing up)

- Nasal congestion

- Nightmares, hallucinations, and psychosis (more severe than with L-dopa for both drugs)

- Sudden sleep attacks. These can be very serious, particularly if patients are driving.

Other Dopamine Agonists.

- Specific dopamine agonists that contain ergot alkaloids include bromocriptine (Parodel generic). Bromocriptine is the only ergot dopamine agonist approved for Parkinson's treatment in the United States.

- Apomorphine is a dopamine agonist used as a "rescue" drug in people having on-off effects severe enough to require going off L-dopa for a few days. It is FDA-approved for treating off-time episodes of Parkinson's disease. Apomorphine is given by injection. Because it causes severe nausea and vomiting, it must be taken with an anti-nausea drug.

- Rotigotine (Neupro) is a once-daily transdermal patch that releases a steady level of the drug through the skin to treat symptoms associated with early- and advanced-stage Parkinson’s.

Catechol-O-Methyl Transferase (COMT) Inhibitors

Catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT) inhibitors increase concentrations of existing dopamine in the brain. Entacapone (Comtan, Stalevo) is the current standard COMT inhibitor. (Stalevo combines entacapone and levodopa in a single pill.) It improves motor fluctuations related to the wearing-off effect and has shown good results in improving on time and reducing the requirements for L-dopa. If the patient does not respond to the drug within 3 weeks, it should be withdrawn. No one should withdraw abruptly from these drugs.

Side Effects. Side effects may include:

- Involuntary muscle movements

- Mental confusion and hallucinations

- Cramps, nausea, and vomiting

- Insomnia

- Headache

- Urine discoloration (a harmless side effect but should be reported to the doctor)

- Diarrhea

- Less commonly, constipation, susceptibility to respiratory infection, sweating, dry mouth

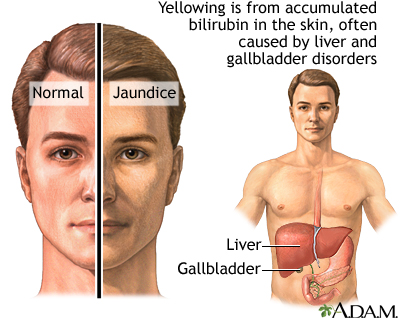

Of major concern are reports of a few deaths from liver damage in patients taking the COMT inhibitor tolcapone (Tasmar). The drug has been taken off the market in many countries and is recommended in the U.S. only for patients who cannot tolerate other drugs. Entacapone does not appear to have the same effects on the liver and does not require monitoring. Still, patients should watch out for symptoms of liver damage, including jaundice (yellowish skin), fatigue, and loss of appetite.

Some data indicate that Stalevo may increase the risk for heart events (heart attack, stroke, and death). The FDA is reviewing this evidence and advises doctors to monitor the heart health of patients taking Stalevo, especially if they have a history of heart disease. The FDA is also investigating whether Stalevo may increase the risk of prostate cancer.

Anticholinergic Drugs

Anticholinergics were the first drugs used for PD, but they have largely been replaced by dopamine drugs. They are generally used only to control tremor in the early stages. They are not as effective against bradykinesia and posture problems and may increase the risk for dementia in late stages. Among the many anticholinergics are trihexyphenidyl (Artane, Trihexane, generic), benztropine (Cogentin, generic), and biperiden (Akineton, generic), Orphenadrine (Norflex, generic) is a drug with anticholinergic properties, but it is also a muscle relaxant and does not cause urinary retention.

Side Effects. Anticholinergics commonly cause dryness of the mouth (which can actually be an advantage in some people who experience drooling). Other side effects are nausea, urinary retention, blurred vision, and constipation. These drugs can increase heart rate and worsen constipation. Anticholinergics can sometimes cause significant mental problems, including memory loss, confusion, and even hallucinations. People with glaucoma should use these drugs with caution.

Amantadine

Amantadine (Symadine, Symmetrel) stimulates the release of dopamine and may be used for patients with early mild symptoms. It has some benefit against muscle rigidity and slowness and may help some patients in advanced stages who are unresponsive to other drugs. It is less powerful than levodopa and may lose its effectiveness after 6 months. It may also reduce motor fluctuations brought on by levodopa, however, and these benefits appear to persist for at least a year. Large, well-conducted studies are still needed to determine its true benefits and safety.

Side Effects. Side effects are similar to those of anticholinergic drugs and may include swollen ankles and mottled skin. Amantadine can also cause visual hallucinations. Overdose can cause serious and even life-threatening toxicity. Patients with Parkinson's should not withdraw from this drug abruptly. In rare instances, it can cause acute delirium or a life-threatening condition called neuroleptic malignant syndrome.

Surgery

Surgical procedures are recommended for specific patients with advanced Parkinson’s disease whose symptoms are not controlled by drug treatments. Surgical treatment cannot cure Parkinson's disease, but it may help control symptoms such as motor fluctuations and dyskinesia. Pallidotomy and thalamotomy are older procedures that destroy tissue in certain parts of the brain. Deep brain stimulation, the current standard surgical practice for Parkinson’s disease, has largely replaced the older operations.

Deep Brain Stimulation

In deep brain stimulation (DBS), also called neurostimulation, an electric pulse generator controls symptoms such as severe tremors, wearing-off fluctuations, and dyskinesia. The generator is similar to a heart pacemaker. It sends electrical pulses to specific regions of the brain. Candidates most likely to benefit from DBS are those who have advanced Parkinson’s, have responded well to levodopa drug treatment, are younger age, and do not have significant cognitive or psychiatric problems.

For treatment of motor symptoms, DBS usually targets one of two areas of the brain: the subthalamic nucleus (STN) or the globus pallidus pars interna (GPi). Research indicates that both areas equally likely to respond well to DBS. DBS targeting the STN may allow patients to use less medication, but treatment of this brain area may worsen depression, apathy, impulsivity, ease of using words, and falls.

For treatment of disabling tremors, DBS may be used to target the STN, GPi, or the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus.

DBS should be performed by an experienced neurosurgeon who is trained in stereotactic neurosurgery (surgery that uses three-dimensional imaging to help target specific areas of the brain).

The procedure is performed as follows:

- Before the procedure, the neurosurgeon uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or other types of imaging techniques to pinpoint the exact areas of the brain where the DBS electrodes will be inserted.

- The neurosurgeon implants a tiny pulse generator near the collarbone, which is connected to four electrodes that have been implanted in the target area in the brain.

- The generator delivers programmed pulses to this area, which the patient can turn on and off using a magnet held over the skin. When on, the pulses suppress symptoms.

- The most common complication is infection at the surgical site.

The benefits of DBS appear to be long lasting, but it may take 3 - 6 months to achieve results. During this time, doctors may need to adjust the implanted device. Researchers are still trying to determine the best surgical techniques for implanting the DBS device, and how to best select the patients who are most likely to benefit.

Pallidotomy and Thalamotomy

Pallidotomy and thalamotomy are surgical procedures that destroy brain tissue in regions of the brain associated with Parkinson’s symptoms, such as dyskinesia, rigidity, and tremor. In these procedures, a surgeon drills a small hole in the patient’s skull and inserts an electrode to destroy brain tissue. Pallidotomy targets the global pallidus area. Thalamotomy targets the thalamus. Because these procedures permanently eliminate brain tissue, most doctors now recommend deep brain stimulation instead of pallidotomy or thalamotomy.

Surgical complications may include behavioral or personality changes, trouble speaking and swallowing, facial paralysis, and vision problems. Weight gain after surgery is also common.

Stem Cell Implantation

Scientists are investigating whether stem cells may eventually help treat Parkinson disease. Experimental surgery has shown promise using fetal brain cells rich in dopamine implanted in the substantia nigra area of the brain. Because the use of embryonic stem cells is controversial, researchers are studying alternative types of cells, including stem cells from adult brains and cells from human placentas or umbilical cords. All of this research is still preliminary.

Lifestyle Changes

Dietary Factors

No special diets or natural foods have been shown to slow the progression of Parkinson's disease, but there are some dietary recommendations.

Protein. High levels of proteins may affect how much levodopa can reach the brain and may, therefore, reduce the drug's effectiveness. Avoiding protein altogether is not the solution, since malnutrition can result. Most doctors recommend reducing protein or eating most of your protein at the evening meal. Patients should discuss a low-protein diet and other nutritional strategies with their health team.

Good control of protein intake may help minimize fluctuations and wearing-off and may allow some patients to reduce their daily levodopa dosage.

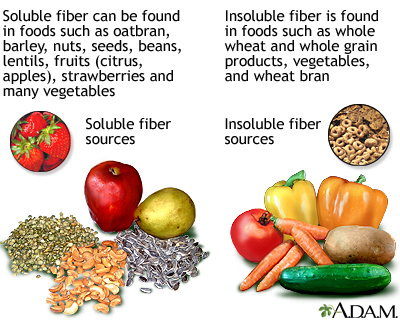

Fruits and Vegetables and Increasing Fiber. Eating whole grains, fresh fruits, and vegetables is the best approach for any healthy life. A diet rich in fruits and vegetables may help protect nerve cell function. Many of these foods are also often rich in fiber, which is particularly important for helping to prevent constipation.

People whose diets have been low in fiber should increase it gradually. It is best to obtain dietary fiber, soluble or insoluble, in the natural form of whole grains, nuts, legumes, fruits, and vegetables. If it proves difficult to do so, psyllium, (found in products such as Metamucil), is an excellent soluble fiber supplement. Drinking lots of fluids is particularly important in preventing constipation.

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

The following dietary supplements are being studied for treatment of Parkinson's disease:

- Creatine. Creatine is a nutritional supplement that is sometimes used to improve exercise performance. In 2007, the U.S. National Institutes of Health launched a large-scale clinical trial to study whether creatine can slow the progression of Parkinson’s disease. The trial will enroll patients who have been diagnosed with PD within the last 5 years and who have received levodopa therapy for no more than 2 years.

- Coenzyme Q10 (Ubiquinone). Coenzyme Q10 (also called ubiquinone) is an antioxidant being studied for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. This enzyme is important for cellular energy, which may be impaired in PD. However, a high-quality study was unable to demonstrate a benefit for low dosages of this dietary supplement. Researchers are still investigating whether larger doses given over a long period of time may help some patients.

Rehabilitation Therapies

Exercise is an important component of rehabilitation. Physical therapy can help with physical function and quality of life. It usually includes active and passive exercise, gait training, and practice in normal activities. To date, no specific exercise approach has been proven to be better than others.

Exercise Programs. Exercise programs are defined as passive or active.

- Passive exercise, mostly stretching and manipulation of muscles by a physical therapist, is aimed at preventing muscles from shortening. A passive exercise program that begins with slow and gentle exercises and becomes progressively more intense may improve mobility in patients with early and mid-stage Parkinson's disease.

- Active exercises are used to help range-of-motion, coordination, and speed. Patients should continually make efforts to practice movement, even simple ones, such as marching in place, making circular arm movements, and raising the legs up and down while sitting. Patients who enjoy sports or the use of exercise equipment should continue with these activities even if their skills diminish, assuming there are no other medical conditions that would prevent participation.

Gait Training. Practicing new methods for standing, walking, and turning may help retain balance and reduce the risk of falls. The following tips may be helpful:

- Take large steps when walking forward, raising the toes at the forward step, and hitting the ground with the heel.

- Take small steps while turning.

- When walking or turning, have the legs 12 - 15 inches apart to provide a wide base.

- Do not wear rubber or crepe-soled shoes because they grip the floor and may cause you to fall forward.

- Using devices that keep a rhythmic beat, such a metronome (a simple device used by musicians to keep time), may help to walk faster and take longer steps.

Tai chi, a Chinese martial art that emphasizes slow flowing motions and gentle movements, may help patients with mild-to-moderate Parkinson’s improve strength and balance and reduce the risk of falls. Some research suggests that tango dance may also help with balance and mobility.

Reducing Muscle Freezing. The patient should practice regular daily activities that simplify actions and reduce the incidence of muscle freezing. Most often, freezing occurs when a patient begins to move or is presented with an obstacle. The following tips may be helpful:

- Rock from side to side.

- If the legs feel frozen, lift the toes. This simple action may free spasm in some cases.

- Hum marching tunes. In fact, music has been shown to help people move and to get out of bed in the morning.

- Divide actions into separate events, which may prevent freezing that occurs from trying to coordinate too many physical operations at one time. For instance, when going through a doorway, approach the door, stop at the door, open it, stop, and then walk through the doorway.

- Simply being touched by another person can sometimes release the patient (although a patient with PD should never be pulled or pushed).

Mental Tasks. Mental training is also helpful. Approaches include:

- Select and learn new hobbies that require finger and hand mobility, such as sewing, carpentry, fishing, or playing cards.

- Practice deep breathing and relaxation exercises. These may help maintain proper speech control, control tremor, and reduce anxiety.

- Both the patient and any caregivers should consider psychological therapy and support for depression and loss of motivation. Support programs and groups are widely available and can be invaluable for the patient and the family.

Speech Therapy. Speech therapy may help those who develop a monotone voice and lose volume. Therapy is prescribed to help with speech and to evaluate and monitor swallowing.

Adaptive Equipment and Assistive Devices

A number of devices can be helpful for maintaining stability and preventing falls. Examples include:

- Rails installed where the patient needs support in getting up or down, such as along the bed and in the bathroom

- Chairs with straight backs, firm seats, and arm rests

- Electric beds or mattresses. Sliding boards are also useful for helping patients slide out of bed.)

- Wheelchairs

Resources

- www.ninds.nih.gov -- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- www.aan.com -- American Academy of Neurology

- www.apdaparkinson.org -- American Parkinson's Disease Association

- www.pdf.org -- Parkinson's Disease Foundation

- www.michaeljfox.org -- Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson's Research

- www.wemove.org -- Worldwide Education and Awareness for Movement Disorders

- www.parkinsonsaction.org -- Parkinson's Action Network

References

Ahlskog JE. Cheaper, simpler, and better: tips for treating seniors with Parkinson disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Dec;86(12):1211-6.

Bronstein JM, Tagliati M, Alterman RL, Lozano AM, Volkmann J, Stefani A, et al. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: an expert consensus and review of key issues. Arch Neurol. 2011 Feb;68(2):165. Epub 2010 Oct 11.

Crawford P, Zimmerman EE. Differentiation and diagnosis of tremor. Am Fam Physician. 2011 Mar 15;83(6):697-702.

Follett KA, Weaver FM, Stern M, Hur K, Harris CL, Luo P, et al. Pallidal versus subthalamic deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010 Jun 3;362(22):2077-91.

Goodwin VA, Richards SH, Taylor RS, Taylor AH, Campbell JL. The effectiveness of exercise interventions for people with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2008 Apr 15;23(5):631-40.

Hitzeman N, Rafii F. Dopamine agonists for early Parkinson disease. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Jul 1;80(1):28-30.

Jain L, Benko R, Safranek S. Clinical inquiry. Which drugs work best for early Parkinson's disease? J Fam Pract. 2012 Feb;61(2):106-8.

Katzenschlager R, Head J, Schrag A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Evans A, Lees AJ; Parkinson's Disease Research Group of the United Kingdom. Fourteen-year final report of the randomized PDRG-UK trial comparing three initial treatments in PD. Neurology. 2008 Aug 12;71(7):474-80. Epub 2008 Jun 25.

Lang AE. Parkinsonism. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D, eds. Cecil Textbook of Medicine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 201107:chap 41633.

Lang AE. When and how should treatment be started in Parkinson disease? Neurology. 2009 Feb 17;72(7 Suppl):S39-43.

Lees AJ, Hardy J, Revesz T. Parkinson's disease. Lancet. 2009 Jun 13;373(9680):2055-66.

Lewitt PA. Levodopa for the treatment of Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 4;359(23):2468-76.

Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, Eckstrom E, Stock R, Galver J, et al. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012 Feb 9;366(6):511-9.

Miyasaki JM, Shannon K, Voon V, Ravina B, Kleiner-Fisman G, Anderson K, et al. Practice Parameter: evaluation and treatment of depression, psychosis, and dementia in Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006 Apr 11;66(7):996-1002.

Olanow CW, Stern MB, Sethi K. The scientific and clinical basis for the treatment of Parkinson disease (2009). Neurology. 2009 May 26;72(21 Suppl 4):S1-136.

Pahwa R, Factor SA, Lyons KE, Ondo WG, Gronseth G, Bronte-Stewart H, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of Parkinson disease with motor fluctuations and dyskinesia (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006 Apr 11;66(7):983-95.

Poewe W. Treatments for Parkinson disease--past achievements and current clinical needs. Neurology. 2009 Feb 17;72(7 Suppl):S65-73.

Stowe R, Ives N, Clarke CE, Deane K; van Hilten, Wheatley K, et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of adjuvant treatment to levodopa therapy in Parkinson s disease patients with motor complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Jul 7;(7):CD007166.

Suchowersky O, Reich S, Perlmutter J, Zesiewicz T, Gronseth G, Weiner WJ; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice Parameter: diagnosis and prognosis of new onset Parkinson disease (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2006 Apr 11;66(7):968-75.

Thurman DJ, Stevens JA, Rao JK; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: Assessing patients in a neurology practice for risk of falls (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2008 Feb 5;70(6):473-9.

Weaver FM, Follett K, Stern M, Hur K, Harris C, Marks WJ Jr, et al. Bilateral deep brain stimulation vs best medical therapy for patients with advanced Parkinson disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009 Jan 7;301(1):63-73.

Zanettini R, Antonini A, Gatto G, Gentile R, Tesei S, Pezzoli G. Valvular heart disease and the use of dopamine agonists for Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jan 4;356(1):39-46.

Zesiewicz TA, Sullivan KL, Arnulf I, Chaudhuri KR, Morgan JC, Gronseth GS, et al. Practice Parameter: treatment of nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2010 Mar 16;74(11):924-31.

|

Review Date:

9/10/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |