Sinusitis

Highlights

Sinusitis

Sinusitis is an inflammation or infection of the sinuses, the air-filled chambers in the skull that are located around the nose. Symptoms of sinusitis include thick nasal discharge, facial pain or pressure, fever, and reduced sense of smell. Depending on how long these symptoms last, sinusitis is classified as acute, subacute, chronic, or recurrent. Viruses are the most common cause of acute sinusitis, but bacteria are responsible for most of the serious cases.

Non-Drug Treatment of Sinusitis

Home remedies such as saline (salt) washes or sprays are helpful for removing mucus and relieving congestion. Steam inhalation is also beneficial. Patients with sinusitis should drink plenty of fluids to avoid dehydration. Water, which helps lubricate the mucous membranes, is the best fluid to drink.

Drug Treatment of Sinusitis

Medication depends on the type of sinusitis and its cause. Non-prescription pain relievers such as acetaminophen and ibuprofen can help mild-to-moderate pain symptoms. Decongestants may help relieve congestion, but they do not cure sinusitis. Antihistamines can dry the mucus and sometimes worsen the condition. Cough or cold medication is not recommended for children younger than age 4 years.

Because many cases of acute sinusitis resolve within two weeks with non-prescription treatments and home remedies, doctors generally wait at least 7 - 14 days before prescribing an antibiotic.

For chronic sinusitis, antibiotics and nasal corticosteroids are the main treatments, but this condition is difficult to treat and does not always respond to these drugs. Other drugs may also be prescribed. If drugs are ineffective, some patients with chronic sinusitis may need surgery.

New Guidelines for Managing Acute Bacterial Sinusitis

In 2012, the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) released updated guidelines for recognizing and treating acute bacterial sinusitis. Bacterial sinusitis can be difficult to distinguish from sinusitis caused by a viral infection. It is important to know the difference because viral infections do not respond to antibiotic treatment. The IDSA emphasizes that bacteria cause only 2 – 10% of acute sinusitis cases. Viruses, such as those from the common cold, are the main cause of acute sinusitis. Most cases of acute sinusitis resolve on their own within a few weeks.

The IDSA’s guidelines recommend diagnosing a bacterial rather than viral cause based on how symptoms start, how they progress, and how long they last. When an antibiotic is prescribed, the IDSA recommends amoxicillin-clavulanate as a first choice. Many types of antibiotics formerly used for acute bacterial sinusitis are no longer effective or recommended.

Introduction

Sinusitis (also called rhinosinusitis) is inflammation of the mucous lining of the nasal passages and sinuses. The sinuses are air-filled chambers in the skull (behind the forehead, nasal bones, cheeks, and eyes) that are lined with mucus membranes.Four pairs of sinuses, known as the paranasal air sinuses, connect to the nasal passages (the two airways running through the nose):

- Frontal sinuses (behind the forehead)

- Maxillary sinuses (behind the cheekbones)

- Ethmoid sinuses (behind the nose)

- Sphenoid sinuses (behind the eyes)

Sinusitis occurs if obstruction or congestion cause the paranasal sinus openings to become blocked. When the sinus openings become blocked or too much mucus builds up in the chambers, bacteria and other germs can grow more easily, leading to infection and inflammation.

Sinusitis is classified as acute, subacute, or chronic, or recurrent. The classification is based on how long symptoms last:

- Acute: Less than 4 weeks

- Subacute: 4 - 12 weeks

- Chronic: 12 weeks or longer

- Recurrent: 3 or more acute episodes in 1 year

Causes

Acute sinusitis can be caused by viral, bacterial, or fungal infections. Allergans and environmental irritants are other possible causes. In most cases, acute sinusitis is caused by an upper respiratory tract viral infection, such as the common cold, and usually resolves on its own.

Chronic sinusitis refers to long-term swelling and inflammation of the sinuses. Chronic sinusitis can result from recurring episodes of acute sinusitis or it can be caused by other health conditions like asthma and allergic rhinitis, immune disorders, or structural abnormalities in the nose like deviated septum or nasal polyps.

Viral, Bacterial, and Fungal Infections

Viruses. Viruses cause 90 – 98% of acute sinusitis cases. The typical process leading to acute sinusitis starts with the common cold virus. Most people with colds have inflamed sinuses. These inflammations are typically brief and mild and very few people with colds develop true sinusitis. Instead, colds and flu set the stage by causing inflammation and congestion in the nasal passages (called rhinitis), leading to obstruction in the sinuses. Rhinitis always accompanies sinusitis, which is why sinusitis is also called rhinosinusitis.

Bacteria. A small percentage of cases of acute sinusitis, and possibly chronic sinusitis, are caused by bacteria. Bacteria are normally present in the nasal passages and throat and are normally harmless. However, when a cold or other viral upper respiratory infection blocks the nasal passage and prevents the sinuses from draining, bacteria can multiply within the mucus lining of the sinuses, causing sinusitis. Streptococcus pneumonia, Haemophilius influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis (a common cause of childhood illnesses) are the bacteria most often linked to acute sinusitis. These bacteria plus other strains, such as Staphylococcus aureus, are also associated with chronic sinusitis. (The role of bacteria in chronic sinusitis is still being debated.) Bacterial sinusitis usually causes more severe symptoms and lasts longer than viral sinusitis.

Fungi. An allergic reaction to fungi is a cause of some cases of chronic rhinosinusitis. Aspergillus is the most common fungus associated with sinusitis. Fungal infections tend to occur in people with sinusitis who also have diabetes, leukemia, AIDS, or other conditions that impair the immune system. Fungal infections can also occur in patients with healthy immune systems, but they are far less common.

Allergies, Asthma, and Immune Response

Allergies, asthma, and sinusitis often overlap. Seasonal allergic rhinitis and other allergies that cause mucus blockage may predispose people to develop sinusitis. Many of the immune factors observed in people with chronic sinusitis resemble those that appear in allergic rhinitis, suggesting that in some people sinusitis is due to an allergic response. Asthma is also strongly associated with sinusitis and many people have both conditions. Some studies suggest that sinusitis may worsen asthma symptoms.

Chronic sinusitis and recurrent acute sinusitis are also assocated with disorders that weaken the immune system or produce inflammation in the airways or persistent thickened stagnant mucus. These conditions include diabetes, AIDS, cystic fibrosis, Kartagener's syndrome, and Wegener's granulomatosis.

Structural Abnormalities of the Nasal Passage

Structural abnormalities in the nose can cause blockage and thereby increase the risk for chronic sinusitis. Some abnormalities include:

- Polyps (small benign growths) in the nasal passage block mucous drainage and restrict airflow. Polyps themselves may result from previous sinus infections that caused overgrowth of the nasal membrane.

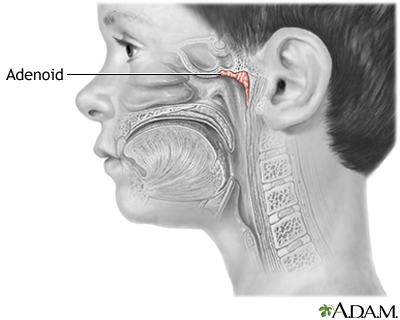

- Enlarged adenoids can lead to sinusitis.

- Cleft palate

- Tumors

- Deviated septum (a common structural abnormality in which the septum, the center section of the nose, is shifted to one side, usually the left)

Risk Factors

Sinusitis is one of the most common diseases in the United States, affecting about 30 million Americans each year.

Young Children and Sinusitis

Before the immune system matures, all infants are susceptible to respiratory infections. Babies catch a cold about every 1 - 2 months. Young children are prone to colds and may have 8 - 12 bouts every year. Smaller nasal and sinus passages make children more vulnerable to upper respiratory tract infections than older children and adults. Ear infections such as otitis media are also associated with sinusitis. Nevertheless, true sinusitis is very rare in children under 9 years of age.

The Elderly and Sinusitis

The elderly are at specific risk for sinusitis. Their nasal passages tend to dry out with age. In addition, the cartilage supporting the nasal passages weakens, causing airflow changes. They also have diminished cough and gag reflexes and weakened immune systems and are at greater risk for serious respiratory infections than are young and middle-aged adults.

People with Asthma or Allergies

People with asthma or allergies are at higher risk for non-infectious inflammation in the sinuses. The risk for sinusitis is higher in patients with severe asthma. People with a combination of polyps in the nose, asthma, and sensitivity to aspirin (called Samter's, or ASA, triad) are at very high risk for chronic or recurrent acute sinusitis.

Hospitalization

Some hospitalized patients are at higher risk for sinusitis, particularly those with:

- Head injuries

- Conditions requiring insertion of tubes through the nose

- Breathing aided by mechanical ventilators

- Weakened immune system (immunocompromised)

Other Medical Conditions Affecting the Sinuses

A number of medical conditions put people at risk for chronic sinusitis. They include:

- Diabetes

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Nasal polyps or septal deviation

- AIDS and other disorders of the immune system

- Oral or intravenous steroid treatment

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid gland) causes congestion that clears up when the condition is treated

- Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder in which the mucus is very thick and builds up

- Kartagener's syndrome, a genetic disorder that impairs function of cilia, the hair-like structures that normally move mucus through the respiratory tract

Miscellaneous Risk Factors

Dental Problems. Bacteria associated with infections from dental problems or procedures can trigger cases of maxillary sinusitis.

Changes in Atmospheric Pressure. People who experience changes in atmospheric pressure, such as while flying, climbing to high altitudes, or swimming, risk sinus blockage and therefore an increased risk of developing sinusitis. (Swimming increases the risk for sinusitis for other reasons, as well.)

Cigarette Smoke and Other Air Pollutants. Air pollution from industrial chemicals, cigarette smoke, or other pollutants can damage the cilia responsible for moving mucus through the sinuses. Whether air pollution is an important cause of sinusitis and, if so, which pollutants are critical factors, is still not clear. Cigarette smoke, for example, poses a small but increased risk for sinusitis in adults. Second-hand smoke does not appear to have any significant effect on adult sinuses, although it may pose a risk for sinusitis in children.

Complications

Bacterial sinusitis is nearly always harmless (although uncomfortable and sometimes even very painful). If an episode becomes severe, antibiotics generally eliminate further problems. In rare cases, however, sinusitis can be very serious.

Osteomyelitis. Adolescent males with acute frontal sinusitis are at particular risk for severe problems. One important complication is infection of the bones (osteomyelitis) of the forehead and other facial bones. In such cases, the patient usually experiences headache, fever, and a soft swelling over the bone known as Pott's puffy tumor.

Infection of the Eye Socket. Infection of the eye socket, or orbital infection, which causes swelling and subsequent drooping of the eyelid, is a rare but serious complication of ethmoid sinusitis. In these cases, the patient loses movement in the eye, and pressure on the optic nerve can lead to vision loss, which is sometimes permanent. Fever and severe illness are usually present.

Blood Clot. Blood clots are another danger, although rare, from ethmoid or frontal sinusitis. If a blood clot forms in the sinus area around the front and top of the face, symptoms are similar to orbital infection. In addition, the pupil may be fixed and dilated. Although symptoms usually begin on one side of the head, the process usually spreads to both sides.

Brain Infection. The most dangerous complication of sinusitis, particularly frontal and sphenoid sinusitis, is the spread of infection by anaerobic bacteria to the brain, either through the bones or blood vessels. Abscesses, meningitis, and other life-threatening conditions may result. In such cases, the patient may experience mild personality changes, headache, altered consciousness, visual problems, and, finally, seizures, coma, and death.

Increased Asthma Severity

The relationship between sinusitis and asthma is unclear. A number of theories have been proposed for a causal or shared association between sinusitis and asthma. Successful treatment of both allergic rhinitis and chronic sinusitis in children who also have asthma may reduce symptoms of asthma. It is particularly important to treat any coexisting bacterial sinusitis in people with asthma. Patients might not respond to asthma treatments unless the infection is cleared up first.

Effects on Quality of Life

Pain, fatigue, and other symptoms of chronic sinusitis can have significant effects on the quality of life. This condition can cause emotional distress, impair normal activity, and reduce attendance at work or school. According to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, the average patient with sinusitis misses about 4 work days a year, and sinusitis is one of the top 10 medical conditions that most adversely affect American employers.

Symptoms

General Symptoms of Acute Sinusitis

Sinus symptoms are very common during a cold or the flu, but in most cases they are due to the effects of the infecting virus and resolve when the infection does. General symptoms of acute sinusitis (both viral and bacterial) include:

- Nasal congestion or discharge

- Headache

- Facial pain or pressure

- Cough or scratchy throat

- Fever

- Diminished or absent sense of smell

- Other symptoms may include ear pain or pressure, dental pain, bad breath, fatigue

Acute Bacterial Sinusitis Symptoms

It is important to differentiate between inflamed sinuses associated with cold or flu virus and sinusitis caused by bacteria but it can be difficult to do so. In general, with viral sinusitis symptoms usually last 7 - 10 days and then improve. Acute bacterial sinusitis, in contrast to viral sinusitis, usually takes one of the following three paths:

- Persistent symptoms that last more than 10 days and do not improve. Nasal discharge either clear or colored and daytime cough are common.

- Severe symptoms, with by a high fever (at least 102 degrees) and thick, green nasal discharge or facial pain that last for at least 3 - 4 days starting from the beginning of the illness. (With viral sinusitis, fever usually disappears within the first day or two and green discharge does not appear until after the fourth day.)

- Worsening symptoms following a typical viral upper respiratory infection. These symptoms appear to improve but are then followed suddenly by another set of worsening symptoms (return of fever, cough, severe headache or increase in nasal discharge) after 5 - 6 days (“double-sickening”)

If symptoms suggest acute bacterial sinusitis, antibiotic treatment is warranted. Bacterial sinusitis is not as common as viral sinusitis, but bacteria are responsible for most of the serious cases of sinusitis.

In children, the most common signs and symptoms of bacterial sinusitis are cough, nasal discharge, and fever. Bad breath is also a common symptom in young children. Headache and facial pain are rare.

Chronic Sinusitis Symptoms

With chronic sinusitis:

- Any of the sinusitis symptoms listed previously may be present

- Symptoms are more vague and generalized than acute sinusitis

- Fever may be absent or just low grade

- Symptoms of sinusitis last 12 weeks or longer

- Symptoms occur throughout the year, even during nonallergy seasons

Symptoms Indicating Medical Emergency

Rare complications of sinusitis can produce additional symptoms, which may be severe or even life threatening. Symptoms indicating a medical emergency include:

- Increasing severity of symptoms

- Eyes may be red, bulging, or painful if the sinus infection occurs around the eyes

- Swelling and drooping eyelid

- Loss of eye movement (possible orbital infection, which is in the eye socket)

- Vision changes

- Pupil fixed or dilated

- Symptoms spreading to both sides of face (may indicate blood clot)

- Development of severe headache, altered vision

- Mild personality or mental changes (may indicate spread of infection to brain)

- A soft swelling over the bone (may indicate bone infection)

Other Causes of Sinusitis Symptoms

Allergies. Symptoms of both sinusitis and allergic rhinitis include nasal obstruction and congestion. The conditions often occur together. People with allergies and no sinus infection may have:

- Thin, clear, and runny nasal discharge

- Itchy nose, eyes, or throat (do not occur with bacterial sinusitis)

- Recurrent sneezing

- Symptoms of allergies appear only during exposure to allergens

Migraine and Other Headaches. Many primary headaches, particularly migraine or cluster, may closely resemble sinus headache. Migraine and sinus headaches may even coexist in many cases. Sinus headaches are usually more generalized than migraines, but it is often difficult to tell them apart, particularly if headache is the only symptom of sinusitis.

Trigeminal Neuralgia. In some cases, headache that persists after successful treatment of chronic sinusitis may be due to neuralgia (nerve-related pain) in the face.

Other Conditions. A number of other conditions can mimic sinusitis. They include:

- Dental problems

- A foreign object in the nasal passage

- Temporal arteritis (headache caused by inflamed arteries in the head)

- Persistent upper respiratory tract infections

- Temporomandibular disorders (problems in the joints and muscles of the jaw hinges)

- Vasomotor rhinitis, a condition in which the nasal passages become congested in response to irritants or stress. It often occurs in pregnant women.

Diagnosis

Patients should see a doctor if they have sinusitis symptoms that do not clear up within a few days, are severe, or are accompanied by high fever or acute illness.

The first goal in diagnosing sinusitis is to rule out other possible causes of symptoms, and then determine:

- The site where the infection has occurred

- Whether the condition is acute or chronic

- The organism causing the infection (if possible)

Diagnostic Approach to Acute Sinusitis

Medical History. The patient should describe all symptoms such as nasal discharge and specific pain in the face and head, including eye and tooth pain.

After assessing symptoms, the doctor should take a thorough medical history of the patient:

- Any history of allergies or headaches

- Recent upper respiratory infections (colds, flu, and infection) and how long they lasted

- History of sinusitis episodes that did not respond to antibiotic treatment. (In such cases, the doctor will usually diagnose chronic or recurrent acute sinusitis and may refer the patient to a specialist for more advanced testing.)

- Exposure to cigarette smoke or other environmental pollutants

- Recent travel (especially by air), scuba diving

- Recent dental procedures

- Medications being taken (particularly decongestants)

- Any known structural abnormalities in the nose and face

- Injury to the head or face

- History of medical conditions that can produce tender areas in the face or sinus regions and nonspecific symptoms of ill health

- Any family history of allergies, immune disorders, cystic fibrosis, or Kartagener's (immotile cilia) syndrome

- In small children with sinusitis, whether they attend a day care center or nursery school

Physical Examination

The doctor will press the forehead and cheekbones to check for tenderness and other signs of sinusitis, including yellow to yellow-green nasal discharge. The doctor will also check the inside of the nasal passages using a device with a bright light to check the mucus and look for any structural abnormalities.

Nasal Endoscopy (Rhinoscopy)

Nasal endoscopy, or rhinoscopy, involves the insertion of a flexible tube with a fiber-optic light on the end into the nasal passage. Rhinoscopy allows detection of even very small abnormalities in the nasal passages and can evaluate structural problems of the nasal septum, as well as the presence of soft tissue masses such as polyps. It may also identify small amounts of pus draining from the opening of a sinus. Bacterial cultures can also be taken from samples removed using endoscopy. (Endoscopy is also used for treating sinusitis.)

Imaging Techniques

Computer Tomography. Computed tomography (CT) scanning is the best method for viewing the paranasal sinuses. There is little relationship, however, between symptoms in most patients and findings of abnormalities on a CT scan. CT scans are recommended for acute sinusitis only if there is a severe infection, complications, or a high risk for complications. CT scans are useful for diagnosing chronic or recurrent acute sinusitis and for surgeons as a guide during surgery. They show inflammation and swelling and the extent of the infection, including in deeply hidden air chambers missed by x-rays and nasal endoscopy. They may also detect the presence of fungal infections.

X-Rays. Until the availability of endoscopy and CT scans, x-rays were commonly used. They are not as accurate, however, in identifying abnormalities in the sinuses. For example, more than one x-ray is needed for diagnosing frontal and sphenoid sinusitis. X-rays do not detect ethmoid sinusitis as accurately. This area can be the primary site of an infection that has spread to the maxillary or frontal sinuses.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is not as effective as CT in defining the paranasal anatomy and therefore is not typically used to image the sinuses for suspected sinusitis. MRI is also more expensive than CT. However, it can help rule out fungal sinusitis and may help differentiate between inflammatory disease, malignant tumors, and complications within the skull. It may also be useful for showing soft tissue involvement.

Sinus Puncture and Bacterial Culture

Sinus puncture with bacterial culture is the gold standard for diagnosing a bacterial sinus infection. It is invasive and is performed only when patients are at risk of having unusual infections or serious complications, or if antibiotics have not worked. Sinus puncture involves using a needle to withdraw a small amount of fluid from the sinuses. It requires a local anesthetic and is performed by a specialist. The fluid is then cultured to determine what type of bacteria is causing sinusitis.

Prevention

The best way to prevent sinusitis is to avoid colds and influenza. If you are unable to avoid them, the next best way to prevent sinusitis is to effectively treat colds and influenza.

Good Hygiene and Preventing Transmission

Colds and flu are spread primarily when an infected person coughs or sneezes near someone else. A very common method for transmitting a cold is by shaking hands. Everyone should always wash their hands before eating and after going outside. Ordinary soap is sufficient. Waterless hand cleaners that contain an alcohol-based gel are also effective for everyday use and may even kill cold viruses. (They are less effective, however, if extreme hygiene is required. In such cases, alcohol-based rinses are needed.) Antibacterial soaps add little protection, particularly against viruses. Wiping surfaces with a solution that contains one part bleach to 10 parts water is very effective in killing viruses.

Vaccines

Influenza Vaccine. Because influenza viruses change from year to year, influenza vaccines are redesigned annually to match the anticipated viral strains. Doctors recommend that people receive annual influenza vaccinations in October or November.

Flu vaccines are now recommended for virtually everyone over 6 months of age, except those allergic to eggs or other vaccine compounds.

Pneumococcal Vaccines. The pneumococcal vaccine protects against S. pneumoniae (also called pneumococcal) bacteria, the most common bacterial cause of respiratory infections. Pneumococcal vaccination is recommended for all children and for all adults age 65 and older. The vaccine is also recommended for adults younger than age 65 who have health conditions that compromise their immune system or lower their their risk for infection as well as smokers and patients with asthma. Several effective vaccines are available, one called a 23-valent polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax, Pnu-Immune) for adults and a 13-valent conjugate vaccine (Prevnar 13) for infants and children younger than 2 years. A 13-valent conjugate vaccine was approved for adults in 2012 and doctors are planning new recommendations for its use.

Treatment

General Treatment Approaches

The primary objectives for treatment of sinusitis are reduction of swelling, eradication of infection, draining of the sinuses, and ensuring that the sinuses remain open. Fewer than half of patients reporting symptoms of sinusitis need aggressive treatment. Home remedies can be very useful.

Bacterial sinusitis, which is treated with antibiotics, accounts for only 2 - 10% of acute rhinosinusitis cases. Most cases of sinusitis are caused by viruses, which do not respond to antibiotics. Acute viral sinusitis generally clears up on its own within 7 - 10 days.

It is important to reserve antibiotics for illnesses caused by bacteria. The intense and widespread use of antibiotics has led to a serious global problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Treatment of Acute Sinusitis.

- Support treatment with saline nasal irrigation, steam inhalations, good hydration, and decongestants are appropriate for a minimum of 7 - 10 days for patients with mild-to-moderate symptoms, and may be used for longer.

- A diagnosis of acute bacterial sinusitis is based on how symptoms progress or worsen, and if they last longer than 10 days. Symptoms such as high fever and thick, colored nasal discharge may indicate a bacterial infection. [For more information on distinguishing bacterial from viral sinusitis, see Symptoms section.]

- For patients with acute bacterial sinusitis that requires antibiotic treatment, amoxicillin-clavunate is usually the first choice. [See Medications section.]

Treatment of Chronic Sinusitis.

- Chronic sinusitis typically results from damage to the mucous membrane from a past, untreated acute sinus infection. The role of antibiotic treatment for chronic sinusitis is controversial. Special types of antibiotics may be used, and treatment may be needed for a longer time.

- Corticosteroid nasal spray is a helpful treatment. Some doctors also recommend oral corticosteroids (such as prednisone) for patients who do not respond to nasal corticosteroids or for those patients who have nasal polyps or allergic fungal sinusitis.

- Saline nasal irrigation may be used on an ongoing basis.

- If there is no improvement, surgery may be considered. For some people with chronic sinusitis the condition is not curable, and the goal of treatment is to improve the quality of life.

- A thorough diagnostic work-up should be performed to rule out any underlying conditions, including but not limited to allergies, asthma, any immune problems, gastroesophageal reflux disorder, and structural problems in the nasal passages. If a primary trigger for chronic sinusitis can be identified, it should be treated or controlled if possible.

Hydration

Home remedies that open and hydrate sinuses are often the only treatment necessary for mild sinusitis that is not accompanied by signs of acute infection.

- Drinking plenty of fluids and getting lots of rest when needed is still the best bit of advice to ease the discomforts of the common cold. Water is the best fluid and helps lubricate the mucus membranes. (There is NO evidence that drinking milk will increase or worsen mucus, although milk is a food and should not serve as fluid replacement.)

- Chicken soup does, indeed, help congestion and aches. The hot steam from the soup may be its chief advantage, although other ingredients in the soup may have anti-inflammatory effects. In fact, any hot beverage may have similar soothing effects from steam. Ginger tea, fruit juice, and hot tea with honey and lemon may all be helpful.

- Spicy foods that contain hot peppers or horseradish may help clear sinuses.

- Inhaling steam 2 - 4 times a day is extremely helpful, costs nothing, and requires no expensive equipment. The patient should sit comfortably and lean over a bowl of boiling hot water (no one should ever inhale steam from water as it boils) while covering the head and the bowl with a towel so the steam remains under the cloth. The steam should be inhaled continuously for 10 minutes. A mentholated or other aromatic preparation may be added to the water. Long, steamy showers, vaporizers, and facial saunas are alternatives.

Nasal Wash

A nasal wash can be helpful for removing mucus from the nose and relieving sinusitis symptoms. A saline (salt water) solution can be purchased in a spray bottle at a drug store or made at home. (Mix 1 teaspoon of table, Kosher, or sea salt with 2 cups of warm water. Some people add a pinch of baking soda.) Perform the nasal wash several times a day.

A simple method for administering a nasal wash is:

- Lean over the sink head down.

- Pour some solution into the palm of the hand and inhale it through the nose, one nostril at a time.

- Spit out the remaining solution.

- Gently blow the nose.

Neti pots have also become popular in recent years for prevention and treatment of sinusitis. Nasal irrigation with a saline solution through a neti pot involves:

- Lean over the sink with your head tilted to one side.

- Insert the spout of the neti pot in the upper nostril.

- Slowly pour the salt water into your nose while continuing to breathe through your mouth.

- The water will flow through the upper nostril and out through the lower nostril.

- When the water finishes dripping out, blow your nose.

- Reverse the tilt of your head and repeat the process with the other nostril.

Managing Sinusitis in Patients with Allergies

Patients often have various combinations of allergies, sinusitis, and asthma. Treating each condition is important for improving them all. In addition to decongestants, pain relievers, and expectorants, other remedies are available for people who suffer from nonbacterial sinusitis during allergy season.

- Anti-Inflammatory Drugs. Nasal spray corticosteroids (commonly called steroids) reduce the inflammatory response in the nasal passages and airways. They are important in the treatment of asthma and are considered to be the most effective measure for preventing allergy attacks. Leukotriene-antagonists are also useful for sinusitis symptoms.

- Antihistamines. Antihistamine tablets relieve sneezing and itching and can prevent nasal congestion before an allergy attack. Many brands are available by prescription and over the counter. Because they thicken mucus and make it harder to drain out from the sinuses, they should not be used for sinusitis.

- Immunotherapy. Immunotherapy, commonly called allergy shots, may be considered for patients with severe seasonal allergies that do not respond to treatment. Immunotherapy is the only treatment that affects the cause of allergies.

- All drug treatments have side effects, some very unpleasant and, rarely, serious. Patients may need to try different drugs until they find one that relieves symptoms without producing excessively distressing side effects.

Emergency Treatment

Patients who show signs that infection has spread beyond the nasal sinuses into the bone, brain, or other parts of the skull need emergency care. High dose antibiotics are administered intravenously, and emergency surgery is almost always necessary in such cases.

Severe Fungal Sinusitis. Sinusitis caused by severe fungal infections is a medical emergency. Treatment is aggressive surgery, and high-dose antifungal chemotherapy with a drug such as amphotericin B can be life saving.

Medications

Antibiotics

Antibiotic drugs are used to treat bacterial, not viral, infections. Unfortunately, because of the overuse and improper use of antibiotics, many types of bacteria no longer respond to antibiotic treatment. The bacteria have become “resistant” to these drugs. Due to the problem of bacterial resistance, doctors have had to switch to different or stronger types of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections.

Amoxicillin, a type of penicillin, used to be the main antibiotic used for sinusitis but it has become less effective. Amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin, generic) has replaced amoxicillin as the antibiotic recommended for treating acute bacterial sinusitis in both children and adults. It is a type of penicillin that works against a wide spectrum of bacteria.

Patients who have a history of penicillin allergy cannot take amoxicillin-clavulanate:

- For adults with sinusitis and penicillin allergies, doctors recommend either doxycycline or the fluoroquinolones levofloxacin or moxifloxacin.

- Children should not take doxycycline because it can cause tooth discoloration. Levofloxacin is the standard alternative antibiotic for children with penicillin allergies.

Other types of antibiotics, such as macrolides and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxaole, have also become ineffective for treating acute bacterial sinusitis and are no longer recommended.

Side Effects. Side effects of antibiotics vary according to the specific drug and the patient’s individual response. Many patients experience few side effects, but they many include:

- Upset stomach.

- Vaginal infections. (Taking supplements of acidophilus or eating yogurt with active cultures may help restore healthy bacteria that offset the risk for such infections.)

- Allergic reactions can occur with all antibiotics but are most common with medications derived from penicillin or sulfa. These reactions can range from mild skin rashes to rare but severe, even life-threatening, anaphylactic shock.

- Certain drugs, including some over-the-counter medications, interact with antibiotics. Inform your doctor of all medications you are taking and of any drug allergies.

Corticosteroids

Nasal-spray corticosteroids, most commonly called steroids, are effective drugs for treating allergic rhinitis. Although they are not approved for treating sinusitis, they may be helpful for patients with sinusitis (either chronic or acute) who have a history of allergic rhinitis. Nasal spray steroids can help reduce inflammation and mucus production.

Corticosteroids available in nasal spray form approved for treating nasal allergy symptoms include:

- Triamcinolone (Nasacort, generic). Approved for children over age 6.

- Mometasone furoate (Nasonex). Approved for use in patients as young as age 3.

- Fluticasone (Flonase, generic). Approved for children over age 4.

- Beclomethasone (Beconase, Vancenase), flunisolide (Nasalide, generic), and budesonide (Rhinocort). Approved for children over age 6.

Side Effects. Corticosteroids are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs. Although oral steroids can have many side effects, the nasal-spray form affects only local areas, and the risk for widespread side effects is very low unless the drug is used excessively. Side effects of nasal corticosteroids may include:

- Dryness, burning, stinging in the nasal passage

- Sneezing

- Headaches and nosebleed (these side effects are uncommon but should be reported to your doctor immediately)

Decongestants

Decongestants are drugs that help reduce nasal congestion. They are available in both pill and nasal spray forms. However, decongestants will not cure sinusitis. Nasal decongestants may actually worsen sinusitis by increasing sinus inflammation.

Due to the lack of evidence for the benefit of nasal decongestants in treating sinusitis, the FDA ordered manufacturers of over-the-counter (OTC) nasal decongestant products to remove from their labeling all references to sinusitis. The Infectious Diseases Society of America does not recommend nasal or oral decongestants for patients with acute bacterial sinusitis.

Your doctor may still recommend that you take either an OTC or prescription nasal decongestant to help relieve blockage symptoms associated with sinusitis. If you think you have sinusitis, check with your doctor before taking a decongestant. Do not try to treat sinusitis by yourself.

Decongestants should never be used in infants and children under the age of 4 years, and some doctors recommend not giving them to children under the age of 14. Children are at particular risk for central nervous system side effects including convulsions, rapid heart rates, loss of consciousness, and death.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines are included in many cold and allergy medications. Because they dry and thicken nasal secretions, they make sinus drainage difficult and may worsen sinusitis. Patients with sinusitis should not take antihistamines.

.

Surgery

Surgery can unblock the sinuses when drug therapy is not effective or if there are other complications, such as structural abnormalities or fungal sinusitis.

Insertion of a Drainage Tube

The simplest surgical approach is the insertion of a drainage tube into the sinuses followed by an infusion of sterile water to flush them out.

Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) is the standard procedure for most patients requiring surgical management of chronic sinusitis or polyposis. The procedure allows correction of obstructions, including any polyp and ventilation and drainage to aid healing.

Candidates for the Procedure.

- In general, patients should have tried and failed extensive medical therapy. This usually includes several prolonged courses of broad-spectrum antibiotics, nasal corticosteroids, nasal saline irrigation, allergy testing and immunotherapy where appropriate, and sinus drainage where appropriate.

- Patients with nasal polyps or sinus polyps who have failed intranasal and possibly oral corticosteroids generally require surgery.

- Patients with congenital anatomic abnormalities.

- Patients with evidence of bone involvement.

- Patients with HIV who have chronic or recurrent sinusitis.

Surgery may not be as effective for patients with fungal infections or severe chronic sinusitis.

Procedure. The surgery generally proceeds as follows:

- Adults need only a local anesthetic for the procedure, although a general anesthetic is needed for children.

- Before the procedure, a computed tomography (CT) scan is taken for use by the surgeon in planning the procedure and as a guide to the sinuses during surgery.

- A flexible tube, a miniature camera, and a fiberoptic light source are inserted through a single small opening.

- Instruments are then used to remove diseased bone or tissue and clear obstructions. For instance, shavers are used to gently remove soft tissue. Bone cutters are sometimes used to open the floor of the frontal sinus and restore drainage (called the modified Lothrop procedure). Lasers may be used to remove bone, coagulate the passageways, or clear obstructions.

Complications. Serious complications of FESS are very rare, but may include cerebrospinal fluid leakage, meningitis, hemorrhage, or infection.

Postsurgical Care. Postsurgical care involves the following:

- The patient will experience a dull ache around the nose and sinus cavity that can be treated with pain medication.

- Following surgery, the patient should flush the sinuses twice daily with a saline or alkaline solution.

- Antibiotics may be prescribed for several weeks until postnasal drip has stopped, and corticosteroid sprays and antihistamines may be needed.

Success Rates. It may take several months for the mucous membranes to completely recover, but 85 - 90% of patients have good to excellent relief of their symptoms after surgery. Children may need a second procedure 2 - 3 weeks after the first surgery to remove crusty matter.

Balloon Sinuplasty

A new type of surgical procedure threads a small balloon through the sinus passages. As the balloon is gently opened, the sinus passages expand, allowing drainage to occur. Some doctors think that this procedure is only appropriate for select patients with sinusitis disease in the maxillary (behind cheek bones), frontal (behind the sides of the forehead), and sphenoid (behind the eyes) sinus regions. It may not work for patients with disease in the ethmoid (between the eyes) sinuses, even though sinusitis commonly occurs in this location. More long-term studies are needed.

Invasive Conventional Surgery

Endoscopy is now used in most cases of chronic sinusitis, but in severe cases, invasive surgery using conventional scalpel techniques to remove infected areas may be required. This may be the case with acute ethmoid sinusitis in which pus breaks through the sinus and threatens the eye, with very severe frontal sinusitis, with invasive fungal sinusitis, or when cancer is present in the sinuses.

Resources

- www.entnet.org -- American Academy of Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery

- www.aaaai.org -- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology

- www.acaai.org -- American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology

- www.niaid.nih.gov -- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease

- www.american-rhinologic.org -- American Rhinologic Society

- www.cdc.gov/vaccines -- National Immunization Program

References

Ahovuo-Saloranta A, Borisenko OV, Kovanen N, Varonen H, Rautakorpi UM, Williams JW Jr, et al. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Apr 16;(2):CD000243.

Anon JB. Upper respiratory infections. Am J Med. 2010 Apr;123(4 Suppl):S16-25.

Brook I. Acute and chronic bacterial sinusitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007 Jun;21(2):427-48, vii.

Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, Brozek JL, Goldstein EJ, Hicks LA, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Apr;54(8):e72-e112. Epub 2012 Mar 20.

Dykewicz MS, Hamilos DL. Rhinitis and sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Feb;125(2 Suppl 2):S103-15.

Hamilos DL. Chronic rhinosinusitis: epidemiology and medical management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Oct;128(4):693-707; quiz 708-9. Epub 2011 Sep 3.

Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, Scadding G. Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD006394.

Jarvis D, Newson R, Lotvall J, Hastan D, Tomassen P, Keil T, et al. Asthma in adults and its association with chronic rhinosinusitis: the GA2LEN survey in Europe. Allergy. 2012 Jan;67(1):91-8. Epub 2011 Nov 4.

Ling FT, Kountakis SE. Important clinical symptoms in patients undergoing functional endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2007 Jun;117(6):1090-3.

Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL. Rhinosinusitis diagnosis and management for the clinician: a synopsis of recent consensus guidelines. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 May;86(5):427-43. Epub 2011 Apr 13.

Rabago D, Zgierska A. Saline nasal irrigation for upper respiratory conditions. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Nov 15;80(10):1117-9.

Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Sep;137(3 Suppl):S1-31.

Ryan MW, Marple BF. Allergic fungal rhinosinusitis: diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007 Feb;15(1):18-22.

Sacks PL, Harvey RJ, Rimmer J, Gallagher RM, Sacks R. Topical and systemic antifungal therapy for the symptomatic treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Aug 10;(8):CD008263.

|

Review Date:

7/10/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |