Hypothyroidism

Highlights

What is Hypothyroidism?

Hypothyroidism, also called underactive thyroid, is a condition in which the thyroid gland does not produce enough hormones. Hypothyroidism can be caused by the autoimmune disorder Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, irradiation or surgical removal of the thyroid gland, and medications that reduce thyroid hormone levels. Anyone can develop hypothyroidism, but people who are most at risk include those who are over age 50 and female. However, only a small percentage of people have full-blown (overt) hypothyroidism. Many more have mildly underactive thyroid glands (subclinical hypothyroidism).

Symptoms

Symptoms of hypothyroidism include:

- Fatigue

- Difficulty concentrating

- Feeling cold

- Headache

- Muscle and joint aches

- Weight gain, despite diminished appetite

- Constipation

- Dry skin

- Coarse hair, hair loss

- Hoarse voice

- Depression

- Menstrual irregularities (either heavier-than-normal or lighter-than-normal bleeding)

- Milky discharge from the breasts (galactorrhea)

Diagnosis and Treatment

Hypothyroidism can cause serious complications if left untreated. Fortunately, it can be easily diagnosed with blood tests that measure levels of the thyroid hormone thyroxine (T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). Your doctor may also want to test for antithyroid antibodies and check your cholesterol levels. Based on these test results, the doctor will decide whether to prescribe medication or simply have you get lab tests every 6 - 12 months.

Medications

The standard drug treatment for hypothyroidism is a daily dose of a synthetic thyroid hormone called levothyroxine. This drug helps normalize blood levels of T4, TSH, and a third hormone called triiodothyronine (T3). Many prescription medications can interact with levothyroxine and either increase or decrease its potency. (Make sure your doctor knows all medications you are taking.) Large amounts of dietary fiber can also interfere with levothyroxine treatment. People who eat high-fiber diets may need higher doses of the drug.

Introduction

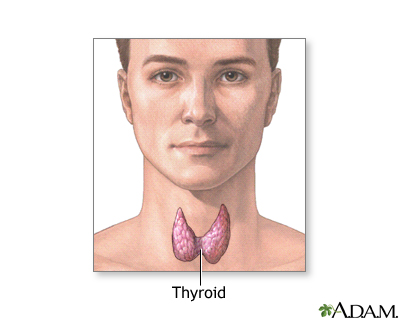

The thyroid is a small, butterfly-shaped gland located in the front of the neck that produces hormones, notably thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3), which stimulate vital processes in every part of the body. These thyroid hormones have a major impact on the following functions:

- Growth

- Use of energy and oxygen

- Heat production

- Fertility

- The use of vitamins, proteins, carbohydrates, fats, electrolytes, and water

- Immune regulation in the intestine

These hormones can also alter the actions of other hormones and drugs.

Iodine and Thyroid Hormone Production

Regulating thyroid function is a complex and important process that involves several factors, including iodine and four thyroid hormones. Any abnormality in this intricate system of hormone synthesis and production can have far-reaching consequences on health.

Iodine. An understanding of the multi-step thyroid hormone process begins with iodine. Eighty percent of the body's iodine supply is stored in the thyroid. Iodine is the material used to make the hormone thyroxine (T4).

Thyroid Hormones. Four hormones are critical in the regulation of thyroid function:

- Thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH), the first critical thyroid hormone, is produced in a region in the brain called the hypothalamus, which monitors and regulates thyrotropin levels.

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), also called thyrotropin, is another very important hormone in the process. Secreted by the pituitary gland, this hormone directly influences the process of iodine trapping and thyroid hormone production. When thyroxine levels drop even slightly, the pituitary gland goes into action to pump up secretion of thyrotropin so that it can stimulate thyroxine production. So, when T4 levels fall, TSH levels increase.

- Thyroxine (T4) and Triiodothyronine (T3). Thyroxine (T4) is the key hormone produced in the thyroid gland. Low levels of T4 produce hypothyroidism, and high levels produce hyperthyroidism. Thyroxine converts to triiodothyronine (T3), which is a more biologically active hormone. Only about 20% of triiodothyronine is actually formed in the thyroid gland. The rest is manufactured from circulating thyroxine in tissues outside the thyroid, such as those in the liver and kidney. Once T4 and T3 are in circulation, they typically bind to substances called thyroid hormone transport proteins, after which they become inactive.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism occurs when thyroxine (T4) levels drop so low that body processes begin to slow down. Hypothyroidism was first diagnosed in the late nineteenth century when doctors observed that surgical removal of the thyroid gland resulted in the swelling of the hands, face, feet, and tissues around the eyes. They named this syndrome myxedema and correctly concluded that it was the outcome of the absence of substances, thyroid hormones, normally produced by the thyroid gland. Hypothyroidism is usually progressive and irreversible. Treatment, however, is nearly always completely successful and allows a patient to live a fully normal life.

Hypothyroidism is separated into either overt or subclinical disease. That diagnosis is determined on the basis of the TSH laboratory blood tests. The normal range of TSH concentration falls between 0.45 - 4.5 mU/L.

- Patients with mildly underactive (subclinical) thyroid have TSH levels of 4.5 - 10mU/L.

- Patients with levels greater than 10mU/L are considered to have overt hypothyroidism and should be treated with medication.

Subclinical, or mild, hypothyroidism (mildly underactive thyroid), also called early-stage hypothyroidism, is a condition in which thyrotropin (TSH) levels have started to increase in response to an early decline in T4 levels in the thyroid. However, blood tests for T4 are still normal. The patient may have mild symptoms (usually slight fatigue) or none at all. Mildly underactive thyroid is very common (affecting about 10 million Americans) and is a topic of considerable debate among doctors because it is not clear how to manage this condition.

Mildly underactive thyroid does not progress to the full-blown disorder in most people. Each year, about 2 - 5% of people with subclinical thyroid go on to develop overt hypothyroidism. Other factors associated with a higher risk of developing clinical hypothyroidism include being an older woman (up to 20% of women over age 60 have subclinical hypothyroidism), having a goiter (enlarged thyroid gland) or thyroid antibodies, or harboring immune factors that suggest an autoimmune condition.

Causes

Many permanent or temporary conditions can reduce thyroid hormone secretion and cause hypothyroidism. About 95% of hypothyroidism cases occur from problems that start in the thyroid gland. In such cases, the disorder is called primary hypothyroidism. (Secondary hypothyroidism is caused by disorders of the pituitary gland. Tertiary hypothyroidism is caused by disorders of the hypothalamus.)

The two most common causes of primary hypothyroidism are:

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis. This is an autoimmune condition in which the body's immune system attacks its own cells.

- Overtreatment of hyperthyroidism (an overactive thyroid).

Autoimmune Diseases of the Thyroid

Hashimoto's thyroiditis, atrophic thyroiditis, and postpartum thyroiditis are all autoimmune diseases of the thyroid. An autoimmune disease occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks the body's own healthy cells. In the case of autoimmune thyroiditis, a common form of primary hypothyroid disease, the cells under attack are in the thyroid gland and include, in particular, a thyroid protein called thyroid peroxidase. The autoimmune disease process results in the destruction of thyroid cells.

Hashimoto's Thyroiditis. The most common form of hypothyroidism in the U.S. is Hashimoto's thyroiditis, a genetic disease named after the Japanese doctor who first described thyroid inflammation (swelling of the thyroid gland). Women are about 7 times more likely than men to develop this disease.

An enlargement of the thyroid gland, called a goiter, is almost always present and may appear as a cyst-like or fibrous growth in the neck. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is permanent and requires lifelong treatment. Both genetic and environmental factors appear to play a role in its development.

The other main type of autoimmune thyroid disease is Graves’ disease, which causes hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid).

Atrophic Thyroiditis. Atrophic thyroiditis is similar to Hashimoto's thyroiditis, except a goiter is not present.

Riedel's Thyroiditis. Riedel's thyroiditis is a rare autoimmune disorder, in which scar tissue progresses in the thyroid until it produces a hard stony mass that suggests cancer. Hypothyroidism develops as the scar tissue replaces healthy tissue. Surgery is usually required, although early stages may be treated with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive drugs.

Autoimmune Thyroiditis Due to Pregnancy. Hypothyroidism may also occur in women who develop antibodies to their own thyroid during pregnancy, causing an inflammation of the thyroid after delivery.

Subacute Thyroiditis

Subacute thyroiditis is a temporary condition that passes through three phases: hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and a return to normal thyroid levels. Patients may have symptoms of both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism (such as rapid heartbeat, nervousness, and weight loss), and they can feel extremely sick. Symptoms last about 6 - 8 weeks and then resolve in most patients, although each form carries some risk for becoming chronic.

The three forms of subacute thyroiditis follow a similar course.

Painless Postpartum Subacute Thyroiditis. Postpartum thyroiditis is an autoimmune condition that occurs in up to 10% of pregnant women and tends to develop between 4 - 12 months after delivery. In most cases, a woman develops a small, painless goiter. It is generally self-limiting and requires no therapy unless the hypothyroid phase is prolonged. If so, therapy may be thyroxine replacement for a few months. A doctor will also prescribe a beta-blocker drug if the hyperthyroid phase needs treatment. About 20% of women with this condition go on to develop permanent hypothyroidism.

Painless Sporadic, or Silent, Thyroiditis. This painless condition is very similar to postpartum thyroiditis except it can occur in both men and women and at any age. About 20% of patients with silent thyroiditis may develop chronic hypothyroidism. Treatment considerations are the same as for postpartum subacute thyroiditis.

Painful, or Granulomatous, Thyroiditis. Subacute granulomatous thyroiditis, also called de Quervain’s disease, comes on suddenly with flu-like symptoms and severe neck pain and swelling. It is thought to be caused by a viral infection and generally occurs in the summer. It is 3 - 5 times more common in women than men. It recurs in about 2% of patients. Hypothyroidism persists in about 5% of patients. Treatments typically include pain relievers and, in severe cases, corticosteroids or beta blockers.

After Treatment of Hyperthyroidism

Up to half or more of patients who receive radioactive iodine treatments for an overactive thyroid develop permanent hypothyroidism within a year of therapy. This is the standard treatment for Graves' disease, which is the most common form of hyperthyroidism, a condition caused by excessive secretion of thyroid hormones.

By the end of 5 years, about 65% of treated patients develop hypothyroidism. Such patients need to take thyroid hormones for the rest of their lives. Other forms of treatment for overactive thyroid glands using either antithyroid drugs or surgery may also result in hypothyroidism.

Iodine Abnormalities

Too much or too little iodine can cause hypothyroidism. If there is a deficiency of iodine, the body cannot manufacture thyroxine. About 200 million people around the world have hypothyroidism because of insufficient iodine in their diets. Too much iodine is a signal to inhibit the conversion process of thyroxine to T3. The end result in both cases is inadequate production of thyroid hormones. Some evidence suggests that excess iodine may trigger the process leading to Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Thyroid Surgery

Patients who have complete removal (total thyroidectomy) of the thyroid gland to treat thyroid cancer need lifetime treatment with thyroid hormone. Removing one of the two lobes of the thyroid gland (hemithyroidectomy), usually because of benign growths on the thyroid gland, rarely produces hypothyroidism. The remaining thyroid lobe will generally grow so that it can produce sufficient amounts of thyroid hormone for normal function. Many doctors recommend thyroid hormone treatment, however, to prevent the formation of additional nodules.

Patients with Graves' disease who have surgery to remove most of both thyroid lobes (subtotal thyroidectomy) may develop hypothyroidism. It is important to find an experienced surgeon for this procedure and to have the thyroid checked at 6- or 12-month intervals.

Drugs and Medical Treatments that Reduce Thyroid Levels

Lithium. Lithium, a drug widely used to treat bipolar disorder, has multiple effects on thyroid hormone synthesis and secretion. About 5 - 35% of patients treated with lithium go on to develop hypothyroidism and up to 50% of patients who take lithium develop a goiter. Most patients develop subclinical hypothyroidism, but a small percentage experience overt hypothyroidism.

Amiodarone. The drug amiodarone (Cordarone), which is used to treat abnormal heart rhythms, contains high levels of iodine and can induce hyper- or hypothyroidism, particularly in patients with existing thyroid problems. Hypothyroidism occurs in about 20% of these patients and is the more common effect in the U.S. and other countries where dietary iodine is abundant. Hyperthyroidism is a less common effect in these regions.

Other Drugs. Drugs used for treating epilepsy, such as phenytoin and carbamazepine, can reduce thyroid levels. Certain antidepressants may cause hypothyroidism, although this is rare. Interferons and interleukins, which are used to treat hepatitis, multiple sclerosis, and other conditions, can also induce hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Some drugs used in cancer chemotherapy, such as sunitinib (Sunent) or imatinib (Gleevec), can also cause or worsen hypothyroidism.

Radiation Therapy. High-dose radiation for cancers of the head or neck and for Hodgkin's disease can cause hypothyroidism up to 10 years after treatment.

Other Medical Conditions

Several medical conditions involve the thyroid and can change the normal gland tissue so that it no longer produces enough thyroid hormone. Examples include hemochromatosis, scleroderma, and amyloidosis.

Causes of Secondary and Tertiary Hypothyroidism

In rare instances, usually due to a tumor, the pituitary gland will fail to produce thyrotropin (TSH), the hormone that stimulates the thyroid to produce its hormones. In such cases, the thyroid gland shrinks. When this happens, secondary hypothyroidism occurs.

Causes of Hypothyroidism in Infants

Hypothyroidism in newborns (known as congenital hypothyroidism) occurs in one in every 3,000 - 4,000 births, making it the most common hormonal disorder in infants. In 90% of these cases, it persists throughout life.

Permanent Congenital Hypothyroidism. In up to 85% of cases of permanent congenital hypothyroidism, the thyroid gland is missing, underdeveloped, or not properly located. In most cases the cause or causes of these conditions are unknown. In about 10 - 15% of cases, processes involved in hormone production are impaired, most likely because of genetic abnormalities. In less than 5% of cases, the pituitary or hypothalamus function abnormally.

Temporary Hypothyroidism in Infants. Temporary hypothyroidism can also occur in infants. In about 20% of cases, the cause is unknown. Known causes stem from various immunologic, environmental, and genetic factors, including those in the mother:

- Women who have an underactive (“low”) thyroid, including those who develop the problem during pregnancy, are at increased risk for delivering babies with congenital (newborn) hypothyroidism. Maternal hypothyroidism can also cause premature delivery and low-birth weight.

- Some of the drugs used to treat hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid) block the production of thyroid hormone. These same drugs can also cross the placenta and cause hypothyroidism in the infant.

- If a pregnant woman has untreated hyperthyroidism, her newborn infant may be hypothyroid for a short period of time. This is because the excess thyroid hormone in the women's blood crosses the placenta and signals the fetus not to produce as much of its own thyroid hormone.

- Iodine deficiency may cause temporary hypothyroidism. (Exposure to too much iodine immediately after birth, for example from iodine-containing disinfectants or medicines, can also cause thyroid dysfunction.)

- Premature birth. Temporary hypothyroidism in infants can occur in premature babies.

- The central nervous system connections between the hypothalamus and pituitary gland may mature late. This condition generally resolves 4 - 16 weeks after birth.

Children with temporary congenital hypothyroidism should be followed up regularly during adolescence and adulthood for possible thyroid problems. The risk for future thyroid problems is highest when girls born with this condition reach adulthood and become pregnant.

Risk Factors

About 15 million Americans have unrecognized thyroid disease, mostly subclinical hypothyroidism (mildly underactive thyroid). Less than 2% of the U.S. population has full-blown (overt) clinical hypothyroidism.

Gender

Women have 10 times the risk of hypothyroidism as men, with the difference being significant after age 34. Because the symptoms of hypothyroidism and menopause can be similar, hypothyroidism may easily be missed.

Pregnancy is a major factor in the higher risk in women. It affects the thyroid in a number of ways and poses a high risk for hypothyroidism, both during pregnancy and afterward. For one, iodine requirements are high in both the mother and the fetus. Changes in reproductive hormones also cause changes in thyroid hormone levels. In addition, some women develop antibodies to their own thyroid during pregnancy, which causes postpartum subacute thyroiditis and can increase the risk of developing permanent hypothyroidism.

Age

The risk for hypothyroidism is greatest after age 50 and increases with age. However, hypothyroidism can affect people of all ages.

Family History

Genetics plays a role in many cases of underactive and overactive thyroid. The genetics involved with hypothyroidism are complicated, however. Thyroid disease will often skip generations. For example, someone with an underactive thyroid may have healthy parents but have grandparents who had thyroid troubles. Some people inherit a tendency for thyroid problems but never become ill, while others become very sick.

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking significantly increases risk for thyroid disease, particularly autoimmune Hashimoto's thyroiditis and postpartum thyroiditis. Smoking also increases the negative effects of hypothyroidism, notably on the arteries and heart.

Medical Conditions Associated with Hypothyroidism

People with certain medical conditions have a higher risk for hypothyroidism. These conditions include:

- Autoimmune diseases. Many autoimmune disorders increase the risk for hypothyroidism. Type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes poses a higher risk and is a special problem since hypothyroidism can affect insulin requirements. Women with other autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus, pernicious anemia, and rheumatoid arthritis, are also at higher risk for hypothyroidism, particularly during pregnancy.

- Gout. Hypothyroidism and gout often coexist and may have biologic mechanisms in common.

- Addison's disease.

- Myasthenia gravis.

- Polycystic ovarian syndrome.

- Eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. In these patients, reduced thyroid function may be an adaptation to malnutrition.

- Turner syndrome. Turner syndrome is a genetic disorder that affects women. As many as half of patients with Turner syndrome have hypothyroidism, usually in the form of Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Many drugs affect the thyroid, so anyone being treated for a chronic disease who takes thyroid medication or is at risk for a thyroid disorder should discuss with their doctor the impact these drugs may have on their thyroid.

Symptoms

Early Symptoms. Early symptoms of hypothyroidism are subtle and, in older people, can be easily mistaken for symptoms of stress or aging. They include:

- Chronic fatigue

- Difficulty concentrating

- Sensitivity to cold

- Headache

- Muscle and joint aches

- Weight gain, despite diminished appetite

- Constipation

- Dry skin

- Menstrual irregularities (either heavier-than-normal or lighter-than-normal bleeding)

- Milky discharge from the breasts (galactorrhea)

Later Symptoms. As free thyroxine levels fall over the following months, other symptoms may develop:

- Impaired mental activity, including problems with concentration and memory, particularly in the elderly.

- Depression.

- Muscle weakness, numbness, pain, and cramps. These symptoms can cause an unsteady gait. Muscle cramps are common, and carpal tunnel syndrome or symptoms similar to arthritis sometimes develop. In some cases, the arms and legs may feel numb.

- Numbness in the fingers.

- Hearing loss.

- Husky voice.

- Continuing weight gain and possible obesity, in spite of low appetite.

- Skin and hair changes. Skin becomes pale, rough, and dry. Patients may sweat less. Hair coarsens and even falls out. Nails become brittle.

- Snoring and obstructive sleep apnea (a condition in which in the soft palate in the throat collapses at intervals during sleep, thereby blocking the passage of air).

Symptoms in Infants and Children

In the U.S., nearly all babies are screened for hypothyroidism in order to prevent cognitive developmental problems that can occur if treatment is delayed. Symptoms of hypothyroidism in children vary depending on when the problem first develops.

- Most children who are born with a defect that causes congenital hypothyroidism have no obvious symptoms. Symptoms that do appear in newborns may include jaundice (yellowish skin), noisy breathing, and an enlarged tongue.

- Early symptoms of undetected and untreated hypothyroidism in infants include feeding problems, failure to thrive, constipation, hoarseness, and sleepiness.

- Later on, symptoms in untreated children include protruding abdomens; rough, dry skin; and delayed teething. Rarely, in advanced cases, yellow raised bumps (called xanthomas) may appear under the skin, the result of cholesterol build-up.

- If they do not receive proper treatment in time, children with hypothyroidism may be extremely short for their age, have a puffy, bloated appearance, and have below-normal intelligence. Any child whose growth is abnormally slow should be examined for hypothyroidism.

Complications

Hypothyroidism increases the risk for physical and mental problems.

Emergency Conditions

Myxedema Coma. Myxedema coma is a rare, life-threatening complication of untreated hypothyroidism. Symptoms include a severe drop in body temperature (hypothermia), delirium, reduced lung function, slow heart rate, constipation, urine retention, seizures, stupor, fluid build-up, and finally coma. It is uncommon but may develop in untreated patients subjected to severe stress, such as those with infection or an extreme cold, or after surgery. Certain drugs (such as sedatives, painkillers, narcotics, amiodarone, and lithium) may increase the risk. Emergency treatment is required. Mortality rates are high (30 - 60%) with the highest risks in older patients and those with persistent hypothermia or heart problems.

Suppurative Thyroiditis. Suppurative thyroiditis is a life-threatening infection of the thyroid gland. It is very rare, since the thyroid is normally resistant to infection. People with pre-existing thyroid diseases, such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis, however, may be at higher than average risk for suppurative thyroiditis. It often begins with an upper respiratory infection. Symptoms include fever, neck pain, rash, and difficulty swallowing and speaking. Immediate treatment is required.

Effects of Hypothyroidism and Subclinical Hypothyroidism on the Heart

Thyroid hormones, particularly triiodothyronine (T3), affect the heart directly and indirectly. They are closely linked with heart rate and heart output. T3 provides particular benefits by relaxing the smooth muscles of blood vessels. This helps keep the blood vessels open so that blood flows smoothly through them.

Hypothyroidism is associated with:

- Unhealthy cholesterol levels. Hypothyroidism raises levels of total cholesterol, LDL ("bad" cholesterol), triglycerides, and other lipids (fat molecules) associated with heart disease. Treating the thyroid condition with thyroid replacement therapy can significantly reduce these levels.

- Mild high blood pressure. Hypothyroidism may slow the heart rate to less than 60 beats per minute, reduce the heart's pumping capacity, and increase the stiffness of blood vessel walls. All of these effects may lead to high blood pressure. Indeed, patients with hypothyroidism have triple the risk of developing hypertension. All patients with chronic hypothyroidism, especially pregnant women, should have their blood pressure checked regularly.

- Heart failure. Hypothyroidism can affect the heart muscle’s contraction and increase the risk of heart failure in people with heart disease.

The evidence for subclinical hypothyroidism’s effects on heart disease is mixed. Some studies, but not all, suggest that subclinical hypothyroidism increases the risks for coronary artery disease and heart failure. More research is needed. Many doctors believe that treatment of subclinical hypothyroidism will not help prevent or improve heart problems.

Effects of Hypothyroidism and Subclinical Hypothyroidism on the Mind

Depression. Depression is common in hypothyroidism and can be severe. Hypothyroidism should be considered as a possible cause of any chronic depression, particularly in older women.

Mental and Behavioral Impairment. Untreated hypothyroidism can, over time, cause mental and behavioral impairment and, eventually, even dementia (memory loss). Whether treatment can completely reverse problems in memory and concentration is uncertain, although many doctors believe that only mental impairment in hypothyroidism that occurs at birth is permanent.

Other Health Effects of Hypothyroidism

The following medical conditions have also been associated with hypothyroidism. Often the causal relationship is not clear in such cases:

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Respiratory problems

- Kidney function

- Glaucoma

- Headache. (Hypothyroidism may worsen headaches in people predisposed to them.)

- Thyroid lymphoma. (Patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis are at higher risk for this rare form of cancer.)

- Joint stiffness. (Women with hypothyroidism may actually have fewer problems with joint stiffness than women with normal thyroid.)

Effects of Hypothyroidism on Infertility and Pregnancy

In premenopausal women, early symptoms of hypothyroidism can interfere with fertility. A history of miscarriage may be a sign of hypothyroidism. (A pregnant woman with hypothyroidism has a fourfold risk for miscarriage.) Studies suggest that even if thyroid levels are normal, women who have a history of miscarriages often have antithyroid antibodies during early pregnancy and are at risk for developing autoimmune thyroiditis over time.

Most women with overt hypothyroidism have menstrual cycle abnormalities and often fail to ovulate. Overt hypothyroidism in a pregnant woman can affect normal fetal development.

Women who have hypothyroidism near the time of delivery are in danger of developing high blood pressure and premature delivery. They are also prone to postpartum thyroiditis, which may be a contributor to postpartum depression.

Effects of Hypothyroidism on Infants and Children

Children of Untreated Mothers. Children born to untreated pregnant women with hypothyroidism are at risk for impaired mental performance, including attention problems and verbal impairment. Studies of children of women with subclinical hypothyroidism are less clear, with some reporting lower IQs in such children and others reporting no significant problems.

Effects of Hypothyroidism During Infancy. Transient hypothyroidism is common among premature infants. Although temporary, severe cases can cause difficulties in neurologic and mental development.

Infants born with permanent congenital (inborn) hypothyroidism need to receive treatment as soon as possible after birth to prevent mental retardation, stunted growth, and other aspects of abnormal development (a syndrome referred to as cretinism). Untreated infants can lose up to 3 - 5 IQ points per month during the first year. An early start of lifelong treatment avoids or minimizes this damage. Even with early treatment, however, mild problems in memory, attention, and mental processing may persist into adolescence and adulthood.

Effects of Childhood-Onset Hypothyroidism. If hypothyroidism develops in children older than 2 years, mental retardation is not a danger, but physical growth may be slowed and new teeth delayed. If treatment is delayed, adult growth could be affected. Even with treatment, some children with severe hypothyroidism may have attention problems and hyperactivity.

Effects of Hypothyroidism and Childhood X-Ray Treatments

Two million Americans, mostly children, received x-ray treatments to the head or neck between 1920 - 1960 for acne, enlarged thymus gland, recurrent tonsillitis, or chronic ear infections. The risk of developing thyroid nodules and thyroid cancers is increased in these individuals, especially if they have hypothyroidism. Cancer can develop as late as 40 years after the original treatment. Everyone who has had head and neck radiation should have their thyroid glands examined regularly.

Diagnosis

Doctors diagnose hypothyroidism after completing a medical history and physical exam of the patient and performing laboratory tests on the patient's blood. Because symptoms of hypothyroidism can mimic those of many other conditions, blood tests for measuring levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free thyroxine (T4) are the only definitive way to diagnose hypothyroidism. However, the results of these blood tests can be affected by illnesses that are not thyroid related.

Physical Examination

The doctor will check the heart, eyes, hair, skin, and reflexes for signs of hypothyroidism.

Goiter. The presence of a goiter (an enlarged thyroid), especially a rubbery, painless one, may be an indication of Hashimoto's disease. If the thyroid is tender and enlarged but not necessarily symmetrical, the doctor may suspect subacute thyroiditis. A diffusely enlarged gland may occur in hereditary hypothyroidism, in postpartum patients, or from use of iodine or lithium. Goiters may also develop in people with iodine deficiency.

Thyroid Hormone and Antibody Tests

In diagnosing hypothyroidism, blood tests measuring thyroid hormone levels are needed to make a correct diagnosis. In some cases, antibody tests are also helpful.

Thyroxine (T4). Hypothyroidism is a condition marked by low thyroxine (T4) hormone levels, and a test can measure levels of this hormone in the blood. However, this test is usually inadequate for the following reasons:

- T4 levels can be normal early in the disease process leading to hypothyroidism. If hypothyroidism is suspected, other tests are needed.

- T4 levels can be low in patients who do not have hypothyroidism. For instance, thyroxine can be extremely variable in very elderly or seriously ill patients and during pregnancy.

Measurements of thyroxine may be accompanied by a process called a T3 resin uptake, which corrects for the presence of medications (such as birth control pills, aspirin, and others) that could distort the T4 results. Other tests are needed to confirm a diagnosis of hypothyroidism.

TSH (Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone). Measuring TSH is the most sensitive indicator of hypothyroidism. (As with thyroxine levels, however, TSH levels can vary in pregnant women and patients who are ill with other conditions.) In general, results indicate the following:

- TSH levels over 10mU/L. This is a clear indicator of hypothyroidism if T4 levels are low -- and, in most cases, even if they are normal. Patients usually need thyroxine (T4) replacement therapy. They should also be tested for high cholesterol levels and antithyroid antibodies.

- Levels between 4.5 - 10 mU/L. Patients with signs and symptoms of hypothyroidism usually need thyroxine replacement therapy. Patients without symptoms have subclinical hypothyroidism and should be rechecked every 6 - 12 months. Antibody tests may also be performed.

- TSH levels between 0.45 - 4.5 mU/L. These indicate normal thyroid function. (Abnormally low levels suggest hyperthyroidism, which is overactive thyroid.)

- Specific TSH measurement -- even if it is significantly higher than 10 mU/L -- is not associated with the severity of the condition. This can be determined only by measuring thyroxine levels and evaluating the patient's symptoms.

Antithyroid Antibodies. If TSH levels suggest hypothyroidism or subclinical hypothyroidism, the doctor may choose to perform a blood test for specific antithyroid antibodies that act against a factor called thyroperoxidase (TPO). Tests can also check for antibodies to thyroglobulin. Results are particularly helpful in deciding how to treat someone with subclinical hypothyroidism.

About 10% of the American population and 25% of women over 60 years old carry these antibodies without having thyroid problems. Only about 0.5% have full-blown hypothyroidism, and 10% have subclinical hypothyroidism.

Other Hormone Tests for Thyroid Function. Other hormone tests may be performed if hyperthyroidism is suspected. They include tests for triiodothyronine (T3) and thyroglobulin (also called thyroid binding globulin). Such measurements also help detect sudden temporary increases in thyroid hormone (thyrotoxicosis) that can precede certain forms of autoimmune thyroiditis.

Imaging Tests

Thyroid Scintigraphy. Thyroid scintigraphy, or scan, can be used to determine which areas of the thyroid are producing normal amounts of hormone. The patient drinks a small amount of radioactive iodine or technetium and waits until the substance has passed through the thyroid. Images of a properly functioning thyroid show uniform levels of absorption throughout the gland. Overactive areas show up white, and underactive areas appear dark. Thyroid scans are more likely to be done to evaluate a goiter (swollen thyroid) or thyroid nodules. They can help identify areas of the gland that may have cancer.

Ultrasound. Ultrasound has limited value, but it can visualize the thyroid and specific abnormalities, such as nodules. (It cannot measure the thyroid gland's function, however.)

More Advanced Imaging Tests. If laboratory tests suggest that a pituitary or hypothalamus problem is causing hypothyroidism, the doctor will usually order brain imaging procedures using computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRIs may also be used for determining the extent of thyroid cancers and of goiters.

Needle Aspiration Biopsy

Needle aspiration biopsy is used to obtain thyroid cells for microscopic evaluation. It may be useful to rule out thyroid cancer in patients with thyroid nodules, abnormal findings on a thyroid scan or ultrasound, or those who have a goiter that is large or feels unusual on physical exam. Much like drawing blood, the doctor injects a small needle into the thyroid gland and draws cells from the gland into a syringe. The cells are put onto a slide, stained, and examined under a microscope.

Other Blood Tests

Cholesterol levels need to be checked. Other blood tests may be performed to detect levels of calcitonin, calcium, prolactin, and thyroglobulin and to check for anemia and liver function, all of which may be affected by hypothyroidism.

Screening Recommendations for Hypothyroidism

Screening in Older Adults. Some doctors believe that because thyroid problems are so common in older adults, and thyroid hormone tests are so inexpensive, blood tests for thyroid function should be routine. Undiagnosed hypothyroidism in elderly patients can develop into a serious and even life-threatening situation. Hyperthyroidism also poses many health risks.

Professional organizations differ widely on screening recommendations. Most do not recommend widespread routine screening for healthy adults.

For organizations that do recommend screening, the American College of Physicians recommends that women over 50 years old be screened for thyroid disorders every 5 years. The American Academy of Family Physicians believes that adults do not have to be screened until they are over 60. The American Thyroid Association recommends that all adults begin their screening at age 35 and every 5 years thereafter.

Screening in Pregnant Women. Current guidelines recommend targeting screening of women before or during pregnancy based on symptoms or medical history. Factors that indicate screening include:

- History of thyroid disease, goiter, type 1 diabetes or other autoimmune illnesses

- History of miscarriages

- History of head and neck radiation or surgery.

Women with these factors should have their thyroid checked before pregnancy, or within the first weeks of pregnancy, and should be retested during each trimester.

Screening in Infants. In the U.S., most newborns are routinely screened for hypothyroidism using a thyroid blood test.

Ruling out Other Disorders

Hypothyroidism can mimic other medical conditions.

Age-Related Disorders. Some symptoms of hypothyroidism and aging are very similar. Menopausal symptoms often resemble hypothyroidism. Many other problems related to aging -- such as vitamin deficiencies, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases, and arthritis -- also have characteristics that can mimic hypothyroidism.

Depression. Drowsiness, fatigue, and difficulty concentrating are signs of clinical depression as well as hypothyroidism. The two disorders often coexist, particularly in older women, so diagnosing one does not rule out the presence of the other.

Diseases of Muscles and Joints. Joint and muscle aches may be initial symptoms of hypothyroidism. Most likely, however, such pain is not caused by hypothyroidism if other thyroid symptoms remain absent. Numerous conditions can cause muscle and joint pain, and if thyroid levels are normal the doctor should look for other causes.

Treatment

A variety of factors affect the decision of whether to treat a patient for hypothyroidism, which dosage to begin with, and how rapidly treatment should be started or increased:

- First, an elevated TSH (thyrotropin) level should be confirmed and thyroxine (T4) level determined. Other thyroid tests may also be helpful.

- Measuring cholesterol levels is also important.

Doctors should also consider:

- Age of the patient

- Presence of other medical problems that may benefit from thyroid replacement treatment (such as heart failure or depression)

- Presence of other medical problems that thyroid replacement therapy may worsen (such as osteoporosis)

Treating Overt Hypothyroidism. Patients with overt hypothyroidism, indicated by clear symptoms and blood tests that show high TSH (generally 10 mU/L and above) and low thyroxine (T4) levels, must have thyroid replacement therapy.

Treating Subclinical or Mild Hypothyroidism. Considerable debate exists about whether to treat patients with subclinical hypothyroidism (slightly higher than normal TSH levels, normal thyroxine levels, and no obvious symptoms). Some doctors opt for treatment and others opt for simply monitoring patients.

It is not clear if the benefits of treating subclinical hypothyroidism outweigh the risks and potential complications. Doctors who recommend against treatment argue that thyroid levels can vary widely, and subclinical hypothyroidism may not persist. In such cases, overtreatment leading to hyperthyroidism is a real risk.

There is reasonable evidence and consensus to recommend treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism in the presence of other factors, including:

- High total or LDL cholesterol levels

- Blood tests that show autoantibodies indicating a future risk for Hashimoto's thyroiditis or other forms of other autoimmune hypothyroidism

- Blood tests that show TSH levels greater than 10 mU/L

- Goiter

- Pregnancy

- Female infertility associated with subclinical hypothyroidism

Treatment is optional in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism who have no obvious symptoms and normal cholesterol levels. Some doctors feel that treating this group of patients will prevent progression to overt hypothyroidism and future heart disease, as well as increase a patient's sense of well-being. However, the evidence to support treatment of this patient group is not nearly as strong. Many doctors recommend against treatment and suggest that these patients should simply have lab tests every 6 - 12 months.

Suppressive Thyroid Therapy. Suppressive thyroid therapy involves taking levothyroxine in doses that are high enough to block the production of natural TSH but too low to cause hyperthyroid symptoms. It may be used for patients with large goiters or thyroid cancer.

Suppressive thyroid therapy places patients, particularly postmenopausal women, at risk for accelerated osteoporosis, a disease that reduces bone mass and increases risk of fractures. However, the cholesterol-lowering benefits of suppressive therapy may outweigh this risk.

Bone density loss can be reduced or avoided by taking no higher a dose of thyroxine than necessary to restore normal thyroid function. In any case, doses of T4 must be continuously and carefully tailored in all patients to avoid adverse effects on the heart.

Treatment of Special Cases

Treating the Elderly and Patients with Heart Disease. Thyroid dysfunction is common in elderly patients, with most having subclinical hypothyroidism. There is no evidence that this condition poses any great harm in this population, and most doctors recommend treating only high-risk patients. Elderly patients, particularly people with heart conditions, usually start with very low doses of thyroid replacement, since thyroid hormone may cause angina or even a heart attack. Patients who have heart disease must take lower-than-average maintenance doses. Doctors do not recommend treatment for subclinical hypothyroidism in most elderly patients with heart disease. Such patients should be closely monitored, however.

Treating Newborns and Infants with Hypothyroidism. Babies born with hypothyroidism (congenital hypothyroidism) should be treated with levothyroxine (T4) as soon as possible to prevent complications. Early treatment can help improve IQ and other developmental factors. However, even with early treatment, mild problems in mental functioning may last into adulthood. In general, children born with milder forms of hypothyroidism will fare better than those who have more severe forms.

Oral levothyroxine (T4) can usually restore normal thyroid hormone levels within 1 - 2 weeks. It is critical that normal levels are achieved within a 2-week period. If thyroid function is not normalized within 2 weeks, it can pose greater risks for developmental problems. Infants should continue to be monitored closely to be sure that thyroxine levels remain as consistently close to normal as possible. These children need to continue lifelong thyroid hormone treatments.

Treatment During Pregnancy and for Postpartum Thyroiditis. Women who have hypothyroidism before becoming pregnant may need to increase their dose of levothyroxine during pregnancy. Women who are first diagnosed with overt hypothyroidism during pregnancy should be treated immediately, with quick acceleration to therapeutic levels. Although not well proven, doctors often recommend treating patients diagnosed with subclinical hypothyroidism while pregnant.

Women with subclinical hypothyroidism who are not treated should be evaluated throughout the pregnancy to see if they progress to overt hypothyroidism. There are no risks to the developing baby when the pregnant woman takes appropriate doses of thyroid hormones. The pregnant woman with hypothyroidism should be monitored regularly (thyroid tests every 4 weeks during the first half of pregnancy) and medication doses adjusted as necessary. If postpartum thyroiditis develops after delivery, any thyroid medication should be reduced or temporarily stopped during this period.

Treatment of Hypothyroidism and Iodine Deficiency. People who are iodine deficient may be able to be treated for hypothyroidism simply by using iodized salt. In addition to iodized salt, seafood is a good source. Except for plants grown in iodine-rich soil, most other foods do not contain iodine. The current RDA for iodine is 150 micrograms for both men and women, with an upper limit of 1,100 micrograms to avoid thyroid injury.

Medications

Thyroid Hormone Replacement

The goal of thyroid drug therapy is to provide the body with replacement thyroid hormone when the gland is not able to produce enough itself.

A synthetic thyroid hormone called levothyroxine is the treatment of choice for hypothyroidism. This drug is a synthetic derivative of T4 (thyroxine), and it normalizes blood levels of TSH, T4, and T3.

Brand Names. A number of levothyroxine brands are available. Synthroid is the oldest brand and has been used for over 40 years. In the past, manufacturers of levothyroxine did not need to meet as strict standards as in the production of other drugs. This resulted in thyroid products with varying quality. The FDA has issued stronger requirements that have largely corrected this problem.

Generics versus Brand-Name Products. Generic brands are available and are subject to the same FDA guidelines as brand-name products. There is still debate over whether generic thyroid preparations are as effective as brand products.

Any change, such as being switched between brand-name and generic or between two different generics, requires additional testing of thyroid hormone levels. Many doctors still prefer to use brand-name products, noting that the cost difference between brand and generic thyroid drugs is not substantial. Regardless of which type is used, once a patient is stable, doctors generally recommend sticking with one type or brand since potency often varies from one drug to the next.

Natural Thyroid Hormone. Dried powdered thyroid hormone (such as Armour Thyroid, S-P-T, Thyrar, and Thyroid Strong) is made from animal glands. It was once the most common form of thyroid therapy, but it is no longer generally recommended because potency varies. Some people argue that, with stricter FDA regulations, this natural form is better controlled and may even reduce the risk of developing autoimmunity factors. Dried thyroid also contains both T3 and T4 and is favored as a natural treatment by many alternative practitioners. However, studies need to be conducted to evaluate its benefits.

T3 and T4 Combinations. Triiodothyronine (T3), the other important thyroid hormone, is not ordinarily prescribed except under special circumstances. Most patients respond well to thyroxine (T4) alone, which is converted in the body into T3. In addition, the use of T3 may cause disturbances in heart rhythms. Some patients treated only with thyroxine continue to have mood and memory problems or other symptoms.

Combination products containing T4 and T3, such as liotrix (Thyrolar), are available, but there is some controversy concerning their benefits. Several recent studies have indicated that, although some patients may prefer combination therapy, T3 and T4 together do not work better than T4 alone. Patients might like the combined drugs because they cause more weight loss, or a placebo effect may be involved. It does not appear that combination products offer any advantage for normalizing TSH levels.

Levothyroxine Regimens

Levothyroxine needs to be taken only once a day. It is slowly assimilated by body organs, so it usually takes up to 6 weeks before symptoms improve in adults. Nevertheless, many patients feel better after 2 - 3 weeks of treatment. The speed at which specific symptoms improve varies:

- Weight loss, less puffiness, and improved pulse usually occur early in the treatment.

- Improvements in anemia and skin, hair, and voice tone may take a few months.

- High LDL ("bad" cholesterol) levels decline very gradually. HDL ("good" cholesterol) levels are not affected by treatment.

- Goiter size declines very slowly, and some patients may need high-dose thyroid hormone (called suppressive thyroid therapy) for a short period.

Levothyroxine reduces blood pressure in about half of hypothyroid patients with hypertension, although blood pressure medications may still be needed.

Appropriate Dosage Levels. Initial dosage levels are determined on an individual basis and can vary widely, depending on a person's age, medical condition, other drugs they are taking, and, in women, whether or not they are pregnant. For example, pregnant women with hypothyroidism may need higher than normal doses.

- Starting out. Most people need to build up gradually until they reach a maintenance dose. In uncomplicated cases, the dose typically starts at 50 micrograms per day, which then increases in 3- to 4-week intervals until thyroid hormone levels are normal. Seniors and those with heart disease may start at 12.5 - 25 micrograms per day. On the other hand, young adults with a short history of hypothyroidism might be able to tolerate a full maintenance dosage right away.

- Maintenance dose. Maintenance dose for most patients averages 112 micrograms, but it can vary between 75 - 260 micrograms. If conditions such as pregnancy, surgery, or other drugs alter hormone levels, the patient's thyroid needs will have to be reassessed.

Daily Regimen. Because thyroid replacement is usually lifelong, setting up a regular daily routine is helpful. Here are some tips to remember:

- Establish a habit of taking the medication at the same time each day. This may help prevent missed doses.

- If you miss a dose of your medicine, take it as soon as you can. If it is almost time for your next dose, take your medicine then and skip the missed dose. Do not use extra medicine to make up for a missed dose.

- Fiber and common daily supplements, such as calcium, may interfere with thyroxine absorption. Although levothyroxine can be taken at any time of day, either with or without food, some doctors recommend taking thyroid hormone upon awakening and at least 30 minutes before eating anything, including breakfast or supplements.

Annual Evaluation. Many factors can cause changes that require modifying the thyroxine dosages. A dose that is appropriate for one year may be too low the next. To maintain normal thyroid levels, some patients may need to take gradually increasing doses of thyroid hormone every year or two. Doctors recommend that patients be reevaluated 6 months after normal TSH levels have been reached and then once a year thereafter.

Specific factors, such as changes in health or diet, new medications for other conditions, or simply switching brands, can also cause changes in thyroid hormone levels that require different doses. If patients change dose levels or thyroxine brands, they should be checked again at least 6 weeks later.

Problems with Levothyroxine Treatment

Because levothyroxine is identical to the thyroxine the body manufactures, side effects are rare. Over- or under-dosing, however, is fairly common, although rarely serious in the short term.

Symptoms of under-dosing include:

- Sluggishness, fatigue, mental dullness

- Feeling cold

- Weight gain

- Constipation

- Muscle cramps

Symptoms of over-dosing include:

- Heart symptoms (rapid heartbeat, palpitations, and wide variations in pulse; possible angina or heart failure)

- Agitation, tremor, nervousness, insomnia

- Feeling warm, flushed skin

- Metabolic symptoms (change in appetite, weight loss)

- Diarrhea

No Symptom Improvement When Normal Thyroid Levels Are Reached. Some patients fail to feel significantly better even when their thyroid levels become normal after taking thyroid replacement.

Some patients with persistent symptoms may benefit from triiodothyronine (T3), the other important thyroid hormone. In such cases, either a combination of a lower-dose of thyroxine with a small amount of T3 or natural dried thyroid hormone, which contains T3, may be helpful.

Side Effects of Overdosing. Overdosing can cause symptoms of hyperthyroidism. A patient with too much thyroid hormone in the blood is at an increased risk for abnormal heart rhythms, rapid heartbeat, heart failure, and possibly a heart attack if the patient has underlying heart disease. Excess thyroid hormone is particularly dangerous in newborns, and their drug levels must be carefully monitored to avoid brain damage.

Side Effects of Long-Term Treatment. Patients with hypothyroidism usually receive lifelong levothyroxine therapy. There has been some concern that long-term use will increase the risk of osteoporosis, as suppression therapy does. Studies indicate that postmenopausal women who are taking long-term replacement thyroxine at the appropriate dosage have no significantly increased risk for osteoporosis.

Drug Interactions with Levothyroxine. Many drugs interact with levothyroxine and may either enhance or interfere with its absorption. These drugs include:

- Amphetamines

- Anticoagulants (blood thinners)

- Tricyclic antidepressants

- Anti-anxiety drugs

- Arthritis medications

- Aspirin

- Beta blockers

- Insulin

- Oral contraceptives

- Digoxin

- Certain cancer drugs

- Iron replacement therapy (ferrous sulfate)

- Calcium carbonate and aluminum hydroxide

- Anticonvulsants (phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine)

- Rifampin (antibiotic used to treat or prevent tuberculosis)

Large amounts of dietary fiber may also reduce the drug’s effectiveness. People whose diets are consistently high in fiber may need larger doses of the drug. Since thyroid hormones regulate the metabolism and can affect the actions of a number of medications, dosages may also need to be adjusted if a patient is being treated for other conditions. Even changing thyroxine brands can have an effect.

Inappropriate Use of Thyroid Hormone

Thyroid replacement hormone is sometimes prescribed inappropriately. It should be used only to treat diagnosed low thyroid. In some cases of infertility, women with menstrual problems and repeated miscarriages and men with low sperm counts have been treated with thyroid hormones even when there was no evidence of thyroid abnormalities.

Other inappropriate uses for thyroid hormones are for weight loss and to reduce high cholesterol levels. Thyroid hormones have also been given to treat so-called metabolic insufficiency. Vague symptoms suggesting low metabolism, such as dry skin, fatigue, slight anemia, constipation, depression, and apathy, should not be treated indiscriminately with thyroid hormone. No evidence exists that thyroid therapy is beneficial unless the patient has proven hypothyroidism. Indiscriminate use of thyroid hormones can weaken muscles and, over the long term, even the heart.

Resources

- www.aace.com -- American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists

- www.thyroid.org -- American Thyroid Association

- www.hormone.org -- Hormone Foundation

- www.endo-society.org -- Endocrine Society

References

Abalovich M, Amino N, Barbour LA, Cobin RH, De Groot LJ, Glinoer D, et al. Management of thyroid dysfunction during pregnancy and postpartum: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007 Aug;92(8 Suppl):S1-47.

Allahabadia A, Razvi S, Abraham P, Franklyn J. Diagnosis and treatment of primary hypothyroidism. BMJ. 2009 Mar 26;338:b725. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b725.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Rose SR; Section on Endocrinology and Committee on Genetics, American Thyroid Association, Brown RS; Public Health Committee, et al. Update of newborn screening and therapy for congenital hypothyroidism. Pediatrics. 2006 Jun;117(6):2290-303.

Brent GA and Davies TF. Hypothyroidism and thyroiditis. In: Melmed S, Polonsky KR, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM, eds. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 12th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 13.

Cooper DS, Biondi B. Subclinical thyroid disease. Lancet. 2012 Mar 24;379(9821):1142-54. Epub 2012 Jan 23.

Fatourechi V. Subclinical hypothyroidism: an update for primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(1):65-71.

Gyamfi C, Wapner RJ, D'Alton ME. Thyroid dysfunction in pregnancy: the basic science and clinical evidence surrounding the controversy in management. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Mar;113(3):702-7.

Jones DD, May KE, Geraci SA. Subclinical thyroid disease. Am J Med. 2010 Jun;123(6):502-4.

LeFranchi S. Hypothyroidism. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme III JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 559.

McDermott MT. In the clinic. Hypothyroidism. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Dec 1;151(11):ITC61.

Ochs N, Auer R, Bauer DC, Nanchen D, Gussekloo J, Cornuz J, Rodondi N. Meta-analysis: subclinical thyroid dysfunction and the risk for coronary heart disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Jun 3;148(11):832-45. Epub 2008 May 19.

Stagnaro-Green A. Maternal thyroid disease and preterm delivery. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 Jan;94(1):21-5. Epub 2008 Nov 4.

Vaidya B, Pearce SH. Management of hypothyroidism in adults. BMJ. 2008 Jul 28;337:a801. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a801.

Villar HC, Saconato H, Valente O, Atallah AN. Thyroid hormone replacement for subclinical hypothyroidism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD003419.

|

Review Date:

5/31/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |