Diabetes diet

Highlights

General Recommendations for Diabetes Diet

- Patients with pre-diabetes or diabetes should consult a registered dietician who is knowledgeable about diabetes nutrition. An experienced dietician can provide valuable advice and help create an individualized diet plan.

- Even modest weight loss can improve insulin resistance (the basic problem in type 2 diabetes) in people with pre-diabetes or diabetes who are overweight or obese. Physical activity, even without weight loss, is also very important.

- The American Diabetes Association (ADA) encourages consumption of healthy fiber-rich foods including fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and legumes. But it is also important to monitor carbohydrate intake through carbohydrate counting, exchanges, or estimation.

- The glycemic index, which measures how quickly a carbohydrate-containing food raises blood sugar levels, may be a helpful addition to carbohydrate counting.

Low-Carb and Low-Fat Diets

- The ADA notes that weight loss plans that restrict carbohydrate or fat intake can help reduce weight in the short term (up to 1 year).

- According to the ADA, the most important component of a weight loss plan is not its dietary composition, but whether or not a person can stick with it. The ADA has found that both low-carb and low-fat diets work equally well, and patients may have a personal preference for one plan or the other.

- Patients with kidney problems need to limit their protein intake and should not replace carbohydrates with large amounts of protein foods. (However, patients who are on dialysis require more protein.)

Introduction

The two major forms of diabetes are type 1, previously called insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) or juvenile-onset diabetes, and type 2, previously called non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) or maturity-onset diabetes.

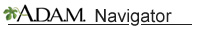

Insulin

Both type 1 and type 2 diabetes share one central feature: elevated blood sugar (glucose) levels due to absolute or relative insufficiencies of insulin, a hormone produced by the pancreas. Insulin is a key regulator of the body's metabolism. It normally works in the following way:

- During and immediately after a meal, digestion breaks carbohydrates down into sugar molecules (of which glucose is one) and proteins into amino acids.

- Right after the meal, glucose and amino acids are absorbed directly into the bloodstream, and blood glucose levels rise sharply. (Glucose levels after a meal are called postprandial levels.)

- The rise in blood glucose levels signals important cells in the pancreas, called beta cells, to secrete insulin, which pours into the bloodstream. Within 10 minutes after a meal insulin rises to its peak level.

- Insulin then enables glucose to enter cells in the body, particularly muscle and liver cells. Here, insulin and other hormones direct whether glucose will be burned for energy or stored for future use.

- When insulin levels are high, the liver stops producing glucose and stores it in other forms until the body needs it again.

- As blood glucose levels reach their peak, the pancreas reduces the production of insulin.

- About 2 - 4 hours after a meal both blood glucose and insulin are at low levels, with insulin being slightly higher. The blood glucose levels are then referred to as fasting blood glucose concentrations.

Type 1 Diabetes

In type 1 diabetes, the pancreas does not produce insulin. Onset is usually in childhood or adolescence. Type 1 diabetes is considered an autoimmune disorder.

Patients with type 1 diabetes need to take insulin. Dietary control in type 1 diabetes is very important and focuses on balancing food intake with insulin intake and energy expenditure from physical exertion.

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes, accounting for 90 - 95% of cases. In type 2 diabetes, the body does not respond normally to insulin, a condition known as insulin resistance. Over time, some patients also run out of insulin. In type 2 diabetes, the initial effect is usually an abnormal rise in blood sugar right after a meal (called postprandial hyperglycemia).

Patients whose blood glucose levels are higher than normal, but not yet high enough to be classified as diabetes, are considered to have pre-diabetes. It is very important that people with pre-diabetes control their weight to stop or delay the progression to diabetes.

Obesity is common in patients with type 2 diabetes, and this condition appears to be related to insulin resistance. The primary dietary goal for overweight type 2 patients is weight loss and maintenance. With regular exercise and diet modification programs, many people with type 2 diabetes can minimize or even avoid medications. Weight loss medications or bariatric surgery may be appropriate for some patients.

General Dietary Guidelines

Lifestyle changes of diet and exercise are extremely important for people who have pre-diabetes, or who are at high risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Lifestyle interventions can be very effective in preventing or postponing the progression to diabetes. These interventions are especially important for overweight people. Even moderate weight loss can help reduce diabetes risk.

The American Diabetes Association recommends that people at high risk for type 2 diabetes eat high-fiber (14g fiber for every 1,000 calories) and whole-grain foods. High intake of fiber, especially from whole grain cereals and breads, can help reduce type 2 diabetes risk.

Patients who are diagnosed with diabetes need to be aware of their heart health nutrition and, in particular, controlling high blood pressure and cholesterol levels.

For people who have diabetes, the treatment goals for a diabetes diet are:

- Achieve near normal blood glucose levels. People with type 1 diabetes and people with type 2 diabetes who are taking insulin or oral medication must coordinate calorie intake with medication or insulin administration, exercise, and other variables to control blood glucose levels.

- Protect the heart and aim for healthy lipid (cholesterol and triglyceride) levels and control of blood pressure.

- Achieve reasonable weight. Overweight patients with type 2 diabetes who are not taking medication should aim for a diet that controls both weight and glucose. A reasonable weight is usually defined as what is achievable and sustainable, and helps achieve normal blood glucose levels. Children, pregnant women, and people recovering from illness should be sure to maintain adequate calories for health.

Overall Guidelines. There is no such thing as a single diabetes diet. Patients should meet with a professional dietitian to plan an individualized diet within the general guidelines that takes into consideration their own health needs.

For example, a patient with type 2 diabetes who is overweight and insulin-resistant may need to have a different carbohydrate-protein balance than a thin patient with type 1 diabetes in danger of kidney disease. Because regulating diabetes is an individual situation, everyone with this condition should get help from a dietary professional in selecting the diet best for them.

Several good dietary methods are available to meet the goals described above. General dietary guidelines for diabetes recommend:

- Carbohydrates should provide 45 - 65% of total daily calories. The type and amount of carbohydrate are both important. Best choices are vegetables, fruits, beans, and whole grains. These foods are also high in fiber. Patients with diabetes should monitor their carbohydrate intake either through carbohydrate counting or meal planning exchange lists.

- Fats should provide 25 - 35% of daily calories. Monounsaturated (such as olive, peanut, canola oils; and avocados and nuts) and omega-3 polyunsaturated (such as fish, flaxseed oil, and walnuts) fats are the best types. Limit saturated fat (red meat, butter) to less than 7% of daily calories. Choose nonfat or low-fat dairy instead of whole milk products. Limit trans-fats (such as hydrogenated fat found in snack foods, fried foods, and commercially baked goods) to less than 1% of total calories.

- Protein should provide 12 - 20% of daily calories, although this may vary depending on a patient’s individual health requirements. Patients with kidney disease should limit protein intake to less than 10% of calories. Fish, soy, and poultry are better protein choices than red meat.

- Lose weight if body mass index (BMI) is 25 - 29 (overweight) or higher (obese).

Several different dietary methods are available for controlling blood sugar in type 1 and insulin-dependent type 2 diabetes:

- Diabetic exchange lists (for maintaining a proper balance of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins throughout the day)

- Carbohydrate counting (for tracking the number of grams of carbohydrates consumed each day)

- Glycemic index (for tracking which carbohydrate foods increase blood sugar)

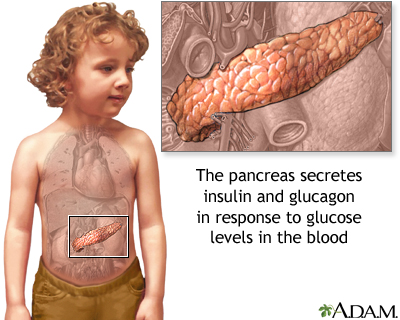

Monitoring

Tests for Glucose Levels. Both low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) and high blood sugar (hyperglycemia) are of concern for patients who take insulin. It is important, therefore, to monitor blood glucose levels carefully. Patients should aim for the following measurements:

- Pre-meal glucose levels of 70 - 130 mg/dL

- Post-meal glucose levels of less than 180 mg/dL

Hemoglobin A1C Test. Hemoglobin A1C (also called HbA1c or HA1c) is measured periodically every 2 - 3 months, or at least twice a year, to determine the average blood-sugar level over the lifespan of the red blood cell. While fingerprick self-testing provides information on blood glucose for that day, the A1C test shows how well blood sugar has been controlled over the period of several months. For most people with well-controlled diabetes, A1C levels should be at around 7%.

Other Tests. Other tests are needed periodically to determine potential complications of diabetes, such as high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and kidney problems. Such tests may also indicate whether current diet plans are helping the patient and whether changes should be made. Periodic urine tests for microalbuminuria and blood tests for creatinine can indicate a future risk for serious kidney disease.

Other Factors Influencing Diet Maintenance

Food Labels. Every year thousands of new foods are introduced, many of them advertised as nutritionally beneficial. It is important for everyone, most especially people with diabetes, to be able to differentiate advertised claims from truth. Current food labels show the number of calories from fat, the amount of nutrients that are potentially harmful (fat, cholesterol, sodium, and sugars) as well as useful nutrients (fiber, carbohydrates, protein, and vitamins).

Labels also show "daily values," the percentage of a daily diet that each of the important nutrients offers in a single serving. This daily value is based on 2,000 calories, which is often higher than what most patients with diabetes should have, and the serving sizes may not be equivalent to those on diabetic exchange lists. Most people will need to recalculate the grams and calories listed on food labels to fit their own serving sizes and calorie needs.

Weighing and Measuring. Weighing and measuring food is extremely important to get the correct number of daily calories.

- Along with measuring cups and spoons, choose a food scale that measures grams. (A gram is very small, about 1/28th of an ounce.)

- Food should be weighed and measured after cooking.

- After measuring all foods for a week or so, most people can make fairly accurate estimates by eye or by holding food without having to measure everything every time they eat.

Timing. Patients with diabetes should not skip meals, particularly if they are taking insulin. Skipping meals can upset the balance between food intake and insulin and also can lead to low blood sugar and even weight gain if the patient eats extra food to offset hunger and low blood sugar levels.

The timing of meals is particularly important for people taking insulin:

- Patients should coordinate insulin administration with calorie intake. In general, they should eat three meals each day at regular intervals. Snacks are often necessary.

- Some doctors recommend a fast acting insulin (insulin lispro) before each meal and a longer (basal) insulin at night.

Special Considerations for People with Kidney Failure

Diabetes can lead to kidney disease and failure. People with early-stage kidney failure need to follow a special diet that slows the build-up of wastes in the bloodstream. The diet restricts protein, potassium, phosphorus, and salt intake. Fat and carbohydrate intake may need to be increased to help maintain weight and muscle tissue.

People who have late-stage kidney disease usually need dialysis. Once patients are on dialysis, they need more protein in their diet. Patients must still be very careful about restricting salt, potassium, phosphorus, and fluids. Patients on peritoneal dialysis may have fewer restrictions on salt, potassium, and phosphorus than those on hemodialysis.

Major Food Components

Carbohydrates

Compared to fats and protein, carbohydrates have the greatest impact on blood sugar (glucose). Except for dietary fiber, which is not digestible, carbohydrates are eventually broken down by the body into glucose. Carbohydrate types are either complex (as in starches) or simple (as in fruits and sugars).

One gram of carbohydrates provides 4 calories. The current general recommendation is that carbohydrates should provide between 45 - 65% of the daily caloric intake. Carbohydrate intake should not fall below 130 grams/day.

Complex carbohydrates are broken down more slowly by the body than simple carbohydrates. They are more likely to provide other nutritional components and fiber.

- Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and beans are good sources of carbohydrates. Whole grain foods provide more nutritional value than pasta, white bread, and white potatoes. Brown rice is a better choice than white rice.

- Patients should try to consume a minimum of 20 - 38 grams of fiber daily (or even up to 50 grams/day), from vegetables, fruits, whole grain products such as cereals and breads, and nuts and seeds.

- Whole grains specifically are extremely important for people with diabetes or those who are at risk for it. [For specific benefits, see: "Whole Grains, Nuts, and Fiber-Rich Foods," below.]

Simple carbohydrates, or sugars (either as sucrose or fructose), adds calories, increases blood glucose levels quickly, and provides little or no other nutrients.

- Sucrose (table sugar) is the source of most dietary sugar, found in sugar cane, honey, and corn syrup.

- Fructose, the sugar found in fruits, produces a smaller increase in blood sugar than sucrose. The modest amounts of fructose in fruit can be handled by the liver without significantly increasing blood sugar but the large amounts in soda and other processed foods with high-fructose corn syrup overwhelm normal liver mechanisms and trigger production of unhealthy triglyceride fats.

- A third sugar, lactose, is a naturally occurring sugar found in dairy products including yogurt and cheese.

People with diabetes should avoid products listing more than 5 grams of sugar per serving, and some doctors recommend limiting fruit intake. You can limit your fructose intake by consuming fruits that are relatively lower in fructose (cantaloupe, grapefruit, strawberries, peaches, bananas) and avoiding added sugars such as those in sugar-sweetened beverages. Fructose is metabolized differently than other sugars and can significantly raise triglycerides.

In addition, avoid processed foods with added sugars of any kind. Pay attention to ingredients in food labels that indicate the presence of added sugars. These include terms such as sweeteners, syrups, fruit juice concentrates, molasses, and sugar molecules ending in “ose” (like dextrose and sucrose).

The Carbohydrate Counting System. Some people plan their carbohydrate intake using a system called carbohydrate counting. It is based on two premises:

- All carbohydrates (either from sugars or starches) will raise blood sugar to a similar degree, although the rate at which blood sugar rises depends on the type of carbohydrate. In general, 1 gram of carbohydrates raises blood sugar by 3 points in people who weigh 200 pounds, 4 points for people who weigh 150 pounds, and 5 points for 100 pounds.

- Carbohydrates have the greatest impact on blood sugar. Fats and protein play only minor roles.

In other words, the amount of carbohydrates eaten (rather than fats or proteins) will determine how high blood sugar levels will rise. There are two options for counting carbohydrates: advanced and simple. Both rely on collaboration with a doctor, dietitian, or both. Once the patient learns how to count carbohydrates and adjust insulin doses to their meals, many find it more flexible, more accurate in predicting blood sugar increases, and easier to plan meals than other systems.

The basic goal is to balance insulin with the amount of carbohydrates eaten in order to control blood glucose levels after a meal. The steps to the plan are as follows:

The patient must first carefully record a number of factors that are used to determine the specific requirements for a meal plan based on carbohydrate grams:

- Multiple blood glucose readings (taken several times a day)

- The time of meals

- Amount in grams of all the carbohydrates eaten

- Time, type, and duration of exercise

- The time, type, and dose of insulin or oral medications

- Other relevant factors, such as menstruation, illness, and stress

The patient works with the dietitian for two or three 45 - 90 minute sessions to plan how many grams of carbohydrates are needed. There are three carbohydrate groups:

- Bread/starch

- Fruit

- Milk

One serving from each group should contain 12 - 15 carbohydrate grams. (Patients can find the amount of carbohydrates in foods from labels on commercial foods and from a number of books and web sites.)

The dietitian creates a meal plan that accommodates the patient's weight and needs, as determined by the patient's record, and makes a special calculation called the carbohydrate to insulin ratio. This ratio determines the number of carbohydrate grams that a patient needs to cover the daily pre-meal insulin needs. Eventually, patients can learn to adjust their insulin doses to their meals.

Patients who choose this approach must still be aware of protein and fat content in foods. These food groups may add excessive calories and saturated fats. Patients must still follow basic healthy dietary principles.

The Glycemic Index. The glycemic index helps determine which carbohydrate-containing foods raise blood glucose levels more or less quickly after a meal. The index uses a set of numbers for specific foods that reflect greatest to least delay in producing an increase in blood sugar after a meal. The lower the index number, the better the impact on glucose levels.

There are two indices in use. One uses a scale of 1 - 100 with 100 representing a glucose tablet, which has the most rapid effect on blood sugar. [See Table: "The Glycemic Index of Some Foods," below.] The other common index uses a scale with 100 representing white bread (so some foods will be above 100).

Choosing foods with low glycemic index scores often has a significant effect on controlling the surge in blood sugar after meals. Many of these foods are also high in fiber and so have heart benefits as well. Substituting low- for high-glycemic index foods may also help with weight control.

One easy way to improve glycemic index is to simply replace starches and sugars with whole grains and legumes (dried peas, beans, and lentils). However, there are many factors that affect the glycemic index of foods, and maintaining a diet with low glycemic load is not straightforward.

No one should use the glycemic index as a complete dietary guide, since it does not provide nutritional guidelines for all foods. It is simply an indication of how the metabolism will respond to certain carbohydrates.

Low-Carbohydrate Diets. Low carb diets generally restrict the amount of carbohydrates but do not restrict protein sources. Popular low-carb diet plans include Atkins, South Beach, The Zone, and Sugar Busters.

- The Atkins diet restricts complex carbohydrates in vegetables and fruits that are known to protect against heart disease. The Atkins diet also can cause excessive calcium excretion in urine, which increases the risk for kidney stones and osteoporosis.

- Low-carb diets such as South Beach, The Zone, and Sugar Busters rely on the glycemic index. Foods on the lowest end of the index take longer to digest. Slow digestion wards off hunger pains. It also helps stabilize insulin levels. Foods high on the glycemic index include bread, white potatoes, and pasta while low-glycemic foods include whole grains, fruit, lentils, and soybeans.

- The Mediterranean Diet is a heart-healthy diet that is rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains as well as healthy monounsaturated fats such as olive oil. It restricts saturated fat proteins like red meat. In studies of patients with type 2 diabetes, a low-carb version of the diet (restricting carbohydrates to less than 50% of total calories) worked better than a low-fat diet in promoting weight loss, reducing A1C levels, and improving insulin sensitivity and glycemic control.

According to the American Diabetes Association (ADA), low-carb diets may help reduce weight in the short term (up to 1 year). However, because these diets tend to include more fat and protein, the ADA recommends that people on these diet plans have their blood lipids, including cholesterol and triglycerides, regularly monitored. Patients who have kidney problems need to be careful about protein consumption, as high-protein diets can worsen this condition.

Whole Grains, Nuts, and Fiber-Rich Foods

Fiber is an important component of many complex carbohydrates. It is found only in plant foods such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, nuts, and legumes (dried beans, peanuts, and peas). Fiber cannot be digested. Instead, it passes through the intestines, drawing water with it, and is eliminated as part of feces content. The following are specific advantages from high-fiber diets (up to 50 grams a day):

- Insoluble fiber (found in wheat bran, whole grains, seeds, nuts, legumes, and fruit and vegetable peels) may help achieve weight loss. Consuming whole grains on a regular basis appears to provide many important benefits, especially for people with type 2 diabetes. Whole grains may even lower the risk for type 2 diabetes in the first place. Of special note, nuts (such as almonds, macadamia, and walnuts) may be highly heart protective, independent of their fiber content. However, nuts are high in calories.

- Soluble fiber (found in dried beans, oat bran, barley, apples, and citrus fruits) has important benefits for the heart, particularly for achieving healthy cholesterol levels and possibly reducing blood pressure as well.

- Soluble fiber supplements, such as those that contain psyllium or glucomannan, may be beneficial. Psyllium is taken from the husk of a seed. It is found in laxatives (Metamucil), breakfast cereals (Bran Buds), and other products. Soluble fiber requires water to help dissolve, so people who increase their levels of soluble fiber should drink more water.

The Glycemic Index of Some Foods | |

Based on 100 = a Glucose Tablet | |

BREADS | |

Pumpernickel | 49 |

Sour dough | 54 |

Rye | 64 |

White | 69 |

Whole wheat | 72 |

GRAINS | |

Barley | 22 |

Sweet corn | 58 |

Brown rice | 66 |

White rice | 72 |

BEANS | |

Soy | 14 |

Red lentils | 27 |

Kidney (dried and boiled, not canned) | 29 |

Chickpeas | 36 |

Baked | 43 |

DAIRY PRODUCTS | |

Milk | 30 |

Ice cream | 60 |

CEREALS | |

Oatmeal | 53 |

All Bran | 54 |

Swiss Muesli | 60 |

Shredded Wheat | 70 |

Corn Flakes | 83 |

Puffed Rice | 90 |

PASTA | |

Spaghetti-protein enriched | 28 |

Spaghetti (boiled 5 minutes) | 33 |

Spaghetti (boiled 15 minutes) | 44 |

FRUIT | |

Strawberries | 32 |

Apple | 38 |

Orange | 43 |

Orange juice | 49 |

Banana | 61 |

POTATOES | |

Sweet | 50 |

Yams | 54 |

New | 58 |

Mashed | 72 |

Instant mashed | 86 |

White | 87 |

SNACKS | |

Potato chips | 56 |

Oatmeal cookies | 57 |

Corn chips | 72 |

SUGARS | |

Fructose | 22 |

Refined sugar | 64 |

Honey | 91 |

Note. These numbers are general values, but they may vary widely depending on other factors, including if and how they are cooked and foods they are combined with. | |

Fat Substitutes and Artificial Sweeteners

Replacing fats and sugars with substitutes may help some people who have trouble maintaining weight.

Fat Substitutes. Fat substitutes added to commercial foods or used in baking, deliver some of the desirable qualities of fat but do not add as many calories. They cannot be eaten in unlimited amounts. Fat substitutes include:

- Plant substances known as sterols, and their derivatives called stanols, reduce cholesterol by blocking its absorption in the intestinal tract. Margarines containing sterols are available.

- Olestra (Olean) passes through the body without leaving behind any calories from fat. However, it can cause cramps and diarrhea, and even small amounts of olestra may prevent the body from absorbing certain vitamins and nutrients.

Artificial Sweeteners. Artificial sweeteners use chemicals to mimic the sweetness of sugar. These products do not contain calories and do not affect blood sugar. Artificial sweeteners approved by the FDA include:

- Aspartame (Nutra-Sweet, Equal). Aspartame is generally considered safe, but people with phenylketonuria (PKU), a rare genetic condition, should not use it.

- Saccharin (Sweet'N Low). Saccharin is the oldest artificial sweeteners. Although early studies in rats indicated a potential risk for cancer, subsequent research has shown that saccharin does not cause cancer.

- Sucralose (Splenda). Sucralose has no bitter aftertaste and works well in baking, unlike other artificial sweeteners. It is made from real sugar by replacing hydroxyl atoms with chlorine atoms.

- Rebiana (Truvia, PureVia) is an extract derived from stevia, a South American plant. (Stevia is also sold in health food stores as a dietary supplement.)

- Acesulfame Potassium, also known as Acesulfame-K (Sweet One, Sunette).

- Neotame (Neotame). Neotame is structurally similar to aspartame. Unlike other artificial sweeteners, neotame is not available as a table sweetener. It is only used as a general-purpose sweetener in commercial food products such as baked goods and soft drinks.

Sugar alcohols (which include xylitol, mannitol, and sorbitol) are often used in “sugar-free” products, such as cookies, hard candies, and chewing gum. Sugar alcohols can slightly increase blood sugar levels. The American Diabetes Association recommends against consuming large amounts of sugar alcohol as it can cause gas and diarrhea, especially in children.

Protein

Protein intake in diabetes is complicated and depends on various factors. These factors include whether a patient has type 1, type 2, or pre-diabetes. There are additional guidelines for patients who show signs of kidney damage (diabetic nephropathy).

In general, diabetes dietary guidelines recommend that proteins should provide 12 - 20% of total daily calories. This daily amount poses no risk to the kidney in people who do not have kidney disease. Protein is important for strong muscles and bones. Some doctors recommend a higher proportion of protein (20 - 30%) for patients with pre- or type 2 diabetes. They think that eating more protein helps people feel more full and thus reduces overall calories. In addition, protein consumption helps the body maintain lean body mass during weight loss.

Patients with diabetic kidney problems need to limit their intake of protein. A typical protein-restricted diet limits protein intake to no more than 10% of total daily calories. Patients with kidney damage also need to limit their intake of phosphorus, a mineral found in dairy products, beans, and nuts. (However, patients on dialysis need to have more protein in their diets.) Potassium and phosphorus restriction is often necessary as well.

One gram of protein provides 4 calories. Protein is commonly recommended as part of a bedtime snack to maintain normal blood sugar levels during the night, although studies are mixed over whether it adds any protective benefits against nighttime hypoglycemia. If it does, only small amounts (14 grams) may be needed to stabilize blood glucose levels.

Good sources of protein include fish, skinless chicken or turkey, nonfat or low-fat dairy products, soy (tofu), and legumes (such as kidney beans, black beans, chick peas, and lentils).

Fish. Fish is probably the best source of protein. Evidence suggests that eating moderate amounts of fish (twice a week) may improve triglycerides and help lower the risks for death from heart disease, dangerous heart rhythms, blood pressure, a tendency for blood clots, and the risk for stroke.

The most healthy fish are oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, or sardines, which are high in omega-3 fatty acids. Three capsules of fish oil (preferably as supplements of DHA-EPA) are about equivalent to one serving of fish.

Women who are pregnant (or planning on becoming pregnant) or nursing should avoid fish that contains high amount of mercury. These high-mercury fish include swordfish, tuna, bass, and mackerel.

Soy. Soy is an excellent food. It is rich in both soluble and insoluble fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, and provides all essential proteins. Soy proteins have more vitamins and minerals than meat or dairy proteins. They also contain polyunsaturated fats, which are better than the saturated fat found in meat. The best sources of soy protein are soy products (such as tofu, soy milk, and soybeans). Soy sauce is not a good source. It contains only a trace amount of soy and is very high in sodium.

For many years, soy was promoted as a food that could help lower cholesterol and improve heart disease risk factors. Recent studies have found that soy protein and isoflavone supplement pills do not have major effects on cholesterol or heart disease prevention. The American Heart Association still encourages patients to include soy foods as part of an overall heart healthy diet but does not recommend using isoflavone supplements.

Meat and Poultry. Lean cuts of meat are the best choice for heart health and diabetes control. Saturated fat in meat is the primary danger to the heart. The fat content of meat varies depending on the type and cut. For patients with diabetes, skinless chicken or turkey is a better choice than red meat. (Fish is an even better choice.)

Dairy Products. A high intake of dairy products may lower risk factors related to type 2 diabetes and heart disease (insulin resistance, high blood pressure, obesity, and unhealthy cholesterol). Some researchers suggest the calcium in dairy products may be partially responsible for these benefits. Vitamin D contained in dairy may also play a role in improving insulin sensitivity, particularly for children and adolescents. However, because many dairy products are high in saturated fats and calories, it’s best to choose low-fat and nonfat dairy items.

Fats and Oils

Some fat is essential for normal body function. Fats can have good or bad effects on health, depending on their chemistry. The type of fat is more important than the total amount of fat when it comes to reducing heart disease. Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are “good” fats that help promote heart health, and should be the main type of fats consumed. Saturated fats and trans fats (trans fatty acids) are “bad” fats that can contribute to heart disease, and should be avoided or limited.

Current dietary guidelines for diabetes and heart health recommend that:

- Total fat from all fat sources should be 25 - 35% of total daily calories.

- Monounsaturated fatty acids (found in olive oil, canola oil, peanut oil, nuts, and avocados) and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (found in fish, shellfish, flaxseed, and walnuts) should be the first choice for fats.

- Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oils and nuts and seeds) are the second choice and should account for 5 - 10% of total calories as part of total fat intake.

- Limit saturated fat (found predominantly in animal products, including meat and full fat dairy products, as well as coconut and palm oils) to less than 7% of total daily calories.

- Limit trans fats (found in margarine, commercial baked goods, snack and fried foods) to less than 1% of total calories.

All fats, good or bad, are high in calories compared to proteins and carbohydrates. In order to calculate daily fat intake, multiply the number of fat grams eaten by nine (1 fat gram provides 9 calories, whether it's oil or fat) and divide by the number of total daily calories desired. One teaspoon of oil, butter, or other fats contains about 5 grams of fat. All fats, no matter what the source, add the same calories. The American Heart Association recommends that fats and oils have fewer than 2 grams of saturated fat per tablespoon.

Try to replace saturated fats and trans fatty acids with unsaturated fats from plant and fish oils. Omega-3 fatty acids, which are found in fish and a few plant sources, are a good source of unsaturated fats. Generally, two servings of fish per week provide a healthful amount of omega-3 fatty acids. Fish oil dietary supplements are another option. Fish and fish oil supplements contain docosahexaenoic (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic (EPA) acids, which have significant benefits for the heart. Discuss with your doctor whether you should consider taking fish oil supplements.

Low-Fat Diets. The American Diabetes Association states that low-fat diets can help reduce weight in the short term (up to 1 year). Low-fat diets that are high in fiber, whole grains, legumes, and fresh produce can offer health advantages for blood sugar and cholesterol control.

Dietary Cholesterol

Animal-based food products contain cholesterol. High amounts occur in meat, dairy products, egg yolks, and shellfish. (Plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, and grains, do not contain cholesterol.) The American Heart Association recommends no more than 300 mg of dietary cholesterol per day for the general population and no more than 200 mg daily for those with high cholesterol or heart disease.

Vitamins and Supplements

Research has shown that vitamin supplements have no benefit for heart disease and diabetes. Because of the lack of scientific evidence for benefit, the American Diabetes Association does not recommend regular use of vitamin supplements, except for people who have vitamin deficiencies.

Patients with type 2 diabetes who take metformin (Glucophage) should be aware that this drug can interfere with vitamin B12 absorption. Calcium supplements may help counteract metformin-associated vitamin B12 deficiency.

Sodium (Salt)

It is important for everyone to restrict their sodium (salt) intake. People with diabetes should reduce sodium intake to less than 1,500 mg daily. Limiting or avoiding consumption of processed foods can go a long way to reducing salt intake. Simply eliminating table and cooking salt is also beneficial.

Salt substitutes, such as Nusalt and Mrs. Dash (which contain mixtures of potassium, sodium, and magnesium) are available, but they can be risky for people with kidney disease or those who take blood pressure medication that causes potassium retention. Similarly, while eating more potassium-rich foods is helpful for achieving healthy blood pressure, patients with diabetes should check with their doctors before increasing the amount of potassium in their diets. [For more information on potassium, see “Other Minerals,” below.]

Other Minerals

Calcium. Calcium supplements may be important in older patients with diabetes to help reduce the risk for osteoporosis, particularly if their diets are low in dairy products.

Potassium and Phosphorus. Potassium-rich foods, and potassium supplements, can help lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Current guidelines encourage enough dietary potassium to achieve 3,500 mg per day for people with normal or high blood pressure (except those who have risk factors for excess potassium levels, including kidney disease and the use of certain medications). This goal is particularly important in people who have high sodium intake.

The best source of potassium is from the fruits and vegetables that contain them. Potassium-rich foods include bananas, oranges, pears, prunes, cantaloupes, tomatoes, dried peas and beans, nuts, potatoes, and avocados.

No one should take potassium supplements without consulting a doctor. Kidney problems can cause potassium overload, and medications commonly used in diabetes (such as ACE inhibitors or potassium-sparing diuretics) also limit the kidney's ability to excrete potassium. Patients with diabetic nephropathy (kidney disease) and kidney failure need to restrict dietary potassium, as well as phosphorus. Phosphorus-rich foods that should be avoided include meats, dairy products, beans, whole foods, and nuts. In addition, many processed and fast foods contain high amounts of phosphorus additives.

Magnesium. Magnesium deficiency may have some role in insulin resistance and high blood pressure. Research indicates that magnesium-rich diets may help lower type 2 diabetes risk. Whole grain breads and cereals, nuts (such as almonds, cashews, and soybeans), and certain fruits and vegetables (such as spinach, avocados, and beans) are excellent dietary sources of magnesium. Dietary supplements do not provide any benefit. Persons who live in soft water areas, who use diuretics, or who have other risk factors for magnesium deficiency may require more dietary magnesium than others.

Chromium. Most studies have indicated that chromium supplements have little or no effect on glucose metabolism and may cause adverse side effects.

Selenium. Selenium, a trace mineral, may increase diabetes risk. An average healthy diet supplies adequate amounts of selenium. There is no need to take dietary supplements.

Zinc. More studies are needed to establish the benefits or risks of taking zinc supplements. Large doses of zinc can have toxic side effects.

Alcohol and Coffee

Alcohol. The American Diabetes Association recommends limiting alcoholic beverages to 1 drink per day for non-pregnant adult women and 2 drinks per day for adult men.

Coffee. Many studies have noted an association between coffee consumption (both caffeinated and decaffeinated) and reduced risk for developing type 2 diabetes. Researchers are still not certain if coffee protects against diabetes.

Herbal Remedies

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been a number of reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Patients should always check with their doctors before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Traditional herbal remedies for diabetes include bitter melon, cinnamon, fenugreek, and Gymnema sylvestre. Few well-designed studies have examined these herbs’ effects on blood sugar, and there is not enough evidence to recommend them for prevention or treatment of diabetes.

Various fraudulent products are often sold on the Internet as “cures” or treatments for diabetes. These dietary supplements have not been studied or approved. The FDA warns patients with diabetes not to be duped by bogus and unproven remedies.

Weight Control for Type 2 Diabetes

The American Diabetes Association recommends that patients aim for a small but consistent weight loss of ½ - 1 pound per week. Most patients should follow a diet that supplies at least 1,000 - 1,200 kcal/day for women and 1,200 - 1,600 kcal/day for men.

Even modest weight loss can reduce the risk factors for heart disease and diabetes. There are many approaches to dieting and many claims for great success with various fad diets. They include calorie restriction, low-fat/high-fiber, or high protein and fat/low carbohydrates.

Here are some general weight-loss suggestions that may be helpful:

- Start with realistic goals. When overweight people achieve even modest weight loss they reduce risk factors in the heart. Ideally, overweight patients should strive for 7% weight loss or better, particularly people with type 2 diabetes.

- A regular exercise program is essential for maintaining weight loss. If there are no health prohibitions, choose one that is enjoyable. Check with a doctor about any health consideration.

- For patients who cannot lose weight with diet alone, weight-loss medications such as orlistat (Alli, Xenical) may be considered. Unfortunately, orlistat produces only modest weight loss and may cause diarrhea.

- For severely obese patients (a body mass index greater than 35), weight loss through bariatric surgery can help in produce rapid weight loss and improve insulin and glucose levels in people with diabetes.

Even repeated weight loss failure is no reason to give up.

Calorie Restriction

Calorie restriction has been the cornerstone of obesity treatment. Restricting calories in such cases also appears to have beneficial effects on cholesterol levels, including reducing LDL and triglycerides and increasing HDL levels.

The standard dietary recommendations for losing weight are:

- As a rough rule of thumb, 1 pound of fat contains about 3,500 calories, so one could lose a pound a week by reducing daily caloric intake by about 500 calories a day. Naturally, the more severe the daily calorie restriction, the faster the weight loss. Very-low calorie diets have also been associated with better success, but extreme diets can have some serious health consequences.

- To determine the daily calorie requirements for specific individuals, multiply the number of pounds of ideal weight by 12 - 15 calories. The number of calories per pound depends on gender, age, and activity levels. For instance a 50-year-old moderately active woman who wants to maintain a weight of 135 pounds and is mildly active might need only 12 calories per pound (1,620 calories a day). A 25-year old female athlete who wants to maintain the same weight might need 25 calories per pound (2,025 calories a day).

- Fat intake should be no more than 30% of total calories. Most fats should be in the form of monounsaturated fats (such as olive oil). Avoid saturated fats (found in animal products).

Exercise

Aerobic exercise has significant and particular benefits for people with diabetes. Regular aerobic exercise, even of moderate intensity (such as brisk walking), improves insulin sensitivity. People with diabetes are at particular risk for heart disease, so the heart-protective effects of aerobic exercise are especially important.

Exercise Precautions for People with Diabetes. The following are precautions for all people with diabetes, both type 1 and type 2:

- Because people with diabetes are at higher than average risk for heart disease, they should always check with their doctors before undertaking vigorous exercise. Moderate-to-high intensity (not high-impact) exercises are best for people who are cleared by their doctors. For people who have been sedentary or have other medical problems, lower-intensity exercises are recommended.

- Strenuous strength training or high-impact exercise is not recommended for people with uncontrolled diabetes. Such exercises can strain weakened blood vessels in the eyes of patients with retinopathy. High-impact exercise may also injure blood vessels in the feet.

- Patients who are taking medications that lower blood glucose, particularly insulin, should take special precautions before embarking on a workout program: Monitor glucose levels before, during, and after workouts (glucose levels swing dramatically during exercise). Avoid exercise if glucose levels are above 300 mg/dl or under 100 mg/dl.

- Inject insulin in sites away from the muscles used during exercise; this can help avoid hypoglycemia.

- Drink plenty of fluids before and during exercise; avoid alcohol, which increases the risk of hypoglycemia.

- Insulin-dependent athletes may need to decrease insulin doses or take in more carbohydrates prior to exercise, but may need to take an extra dose of insulin after exercise (stress hormones released during exercise may increase blood glucose levels).

- Wear good, protective footwear to help avoid injuries and wounds to the feet.

- Some blood pressure drugs may affect exercise capacity. Patients who use blood pressure medication should consult their doctors on how to balance medications and exercise. Patients with high blood pressure should also aim to breathe as normally as possible during exercise. Holding your breath can increase blood pressure.

Diabetic Exchange Lists

The objective of using diabetic exchange lists is to maintain the proper balance of carbohydrates, proteins, and fats throughout the day. Patients should meet with a dietician or diabetes nutrition expert for help in learning this approach.

In developing a menu, patients must first establish their individual dietary requirements, particularly the optimal number of daily calories and the proportion of carbohydrates, fats, and protein. The exchange lists should then be used to set up menus for each day that fulfill these requirements.

The following are some general rules:

- The diabetic exchanges are six different lists of foods grouped according to similar calorie, carbohydrate, protein, and fat content; these are starch/bread, meat, vegetables, fruit, milk, and fat. A person is allowed a certain number of exchange choices from each food list per day.

- The amount and type of these exchanges are based on a number of factors, including the daily exercise program, timing of insulin injections, and whether or not an individual needs to lose weight or reduce cholesterol or blood pressure levels.

- Foods can be substituted for each other within an exchange list but not between lists even if they have the same calorie count.

- In all lists (except in the fruit list) choices can be doubled or tripled to supply a serving of certain foods. (For example 3 starch choices equal 1.5 cups of hot cereal or 3 meat choices equal a 3-ounce hamburger.)

- On the exchange lists, some foods are "free." These contain fewer than 20 calories per serving and can be eaten in any amount spread throughout the day unless a serving size is specified.

Exchange List Categories

The following are the categories on exchange lists:

Starches and Bread. Each exchange under starches and bread contains about 15 grams of carbohydrates, 3 grams of protein, and a trace of fat for a total of 80 calories. A general rule is that a half-cup of cooked cereal, grain, or pasta equals one exchange. One ounce of a bread product is 1 serving.

Meat and Cheese. The exchange groups for meat and cheese are categorized by lean meat and low-fat substitutes, medium-fat meat and substitutes, and high-fat meat and substitutes. Use high-fat exchanges a maximum of 3 times a week. Fat should be removed before cooking. Exchange sizes on the meat list are generally 1 ounce and based on cooked meats (3 ounces of cooked meat equals 4 ounces of raw meat).

Vegetables. Exchanges for vegetables are 1/2 cup cooked, 1 cup raw, and 1/2 cup juice. Each group contains 5 grams of carbohydrates, 2 grams of protein, and 2 - 3 grams of fiber. Vegetables can be fresh or frozen; canned vegetables are less desirable because they are often high in sodium. They should be steamed or cooked in a microwave without added fat.

Fruits and Sugar. Sugars are included within the total carbohydrate count in the exchange lists. Sugars should not be more than 10% of daily carbohydrates. Each exchange contains about 15 grams of carbohydrates for a total of 60 calories.

Milk and Substitutes. The milk and substitutes list is categorized by fat content similar to the meat list. A milk exchange is usually 1 cup or 8 ounces. Those who are on weight-loss or low-cholesterol diets should follow the skim and very low-fat milk lists -- while avoiding the whole milk group. Others should use the whole milk list very sparingly. All people with diabetes should avoid artificially sweetened milks.

Fats. A fat exchange is usually 1 teaspoon, but it may vary. People, of course, should avoid saturated and trans fatty acids and choose polyunsaturated or monounsaturated fats instead.

Number of Exchanges per Day for Various Calories Levels | ||||||

Calories | 1,200 | 1,500 | 1,800 | 2,000 | 2,200 | |

Starch/Bread | 5 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 13 | |

Meat | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | |

Vegetable | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | |

Fruit | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

Milk | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |

Fat | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

Resources

- www.diabetes.org -- American Diabetes Association

- www.niddk.nih.gov -- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- www.jdrf.org -- Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation

- www.kidney.org -- National Kidney Foundation

- www.joslin.org -- Joslin Diabetes Center

- www.eatright.org -- American Dietetic Association

- www.nal.usda.gov/fnic -- Food and Nutrition Information Center

References

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes -- 2012. Diabetes Care. 2012 Jan;35 Suppl 1:S11-63.

American Heart Association Nutrition Committee; Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006 Jul 4;114(1):82-96. Epub 2006 Jun 19.

Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Ciotola M, Di Palo C, Scognamiglio P, Gicchino M, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on the need for antihyperglycemic drug therapy in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Sep 1;151(5):306-14.

Foster GD, Wyatt HR, Hill JO, Makris AP, Rosenbaum DL, Brill C, et al. Weight and metabolic outcomes after 2 years on a low-carbohydrate versus low-fat diet: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Aug 3;153(3):147-57.

Franz MJ, Powers MA, Leontos C, Holzmeister LA, Kulkarni K, Monk A, et al. The evidence for medical nutrition therapy for type 1 and type 2 diabetes in adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Dec;110(12):1852-89.

Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, Kim S, Stafford RS, Balise RR, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007 Mar 7;297(9):969-77.

Gillies CL, Abrams KR, Lambert PC, Cooper NJ, Sutton AJ, Hsu RT, et al. Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007 Feb 10;334(7588):299. Epub 2007 Jan 19.

Harris WS, Mozaffarian D, Rimm E, Kris-Etherton P, Rudel LL, Appel LJ, Engler MM, Engler MB, Sacks F. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2009 Feb 17;119(6):902-7. Epub 2009 Jan 26.

Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, McKeown-Eyssen G, Josse RG, Silverberg J, Booth GL, et al. Effect of a low-glycemic index or a high-cereal fiber diet on type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008 Dec 17;300(23):2742-53.

Layman DK, Clifton P, Gannon MC, Krauss RM, Nuttall FQ. Protein in optimal health: heart disease and type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008 May;87(5):1571S-1575S.

Lindstrom J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, Aunola S, Eriksson JG, Hemio K, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006 Nov 11;368(9548):1673-9.

Martínez-González MA, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Nunez-Cordoba JM, Basterra-Gortari FJ, Beunza JJ, Vazquez Z, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of developing diabetes: prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Jun 14;336(7657):1348-51. Epub 2008 May 29.

McMillan-Price J, Petocz P, Atkinson F, O'Neill K, Samman S, Steinbeck K, et al. Comparison of 4 diets of varying glycemic load on weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in overweight and obese young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 24;166(14):1466-75.

Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, Bittner V, Criqui MH, Ginsberg HN, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 May 24;123(20):2292-333. Epub 2011 Apr 18.

Reis JP, von Mühlen D, Miller ER 3rd, Michos ED, Appel LJ. Vitamin D status and cardiometabolic risk factors in the United States adolescent population. Pediatrics. 2009 Aug 3. [Epub ahead of print]

Schulze MB, Schulz M, Heidemann C, Schienkiewitz A, Hoffmann K, Boeing H. Fiber and magnesium intake and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007 May 14;167(9):956-65.

Schwingshackl L, Strasser B, Hoffmann G. Effects of monounsaturated fatty acids on glycemic control in patients with abnormal glucose metabolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Nutr Metab. 2011 Oct;58(4):290-6. Epub 2011 Sep 9.

Suckling RJ, He FJ, Macgregor GA. Altered dietary salt intake for preventing and treating diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Dec 8;(12):CD006763.

Ting RZ, Szeto CC, Chan MH, Ma KK, Chow KM. Risk factors of vitamin B(12) deficiency in patients receiving metformin. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Oct 9;166(18):1975-9.

|

Review Date:

5/24/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |