Heart-healthy diet

Highlights

Heart-Healthy Diet Guidelines

Key recommendations for a heart-healthy diet include:

- Eat a balanced diet with plenty of high-fiber foods, such as fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and nuts. Reduce consumption of high-calorie, nutrient-poor foods and beverages.

- Eat fish, especially oily fish (such as salmon, trout, and mackerel) at least twice a week. Oily fish are high in omega-3 fatty acids, which help lower the risk of death from heart disease.

- Get at least 5 - 10% of daily calories from omega-6 fatty acids, which are found in vegetable oils such as sunflower, safflower, corn, and soybean as well as nuts and seeds.

- Choose fat-free or low-fat dairy products.

- Limit daily consumption of foods high in saturated fats and cholesterol, such as red meat, whole-fat dairy products, shellfish, and egg yolks.

- Limit consumption of trans fatty acids (found in fast foods and commercially baked products) to less than 1% of total daily calories.

- Replace saturated and trans fats with unsaturated fats from plant and fish oils.

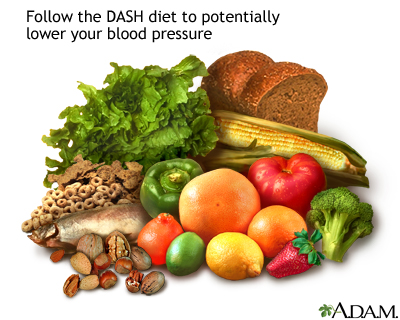

- Restrict your sodium (salt) intake. Try to limit sodium intake to less than 1,500 milligrams a day. This target is especially important for middle-aged and older people, African-Americans, and people with high blood pressure. The DASH diet is a good example of a heart-healthy eating plan that limits sodium intake.

- Choose nutrient-rich fruits instead of beverages and processed foods that contain added sugars

- If you drink alcohol, do so in moderation (1 drink per day for women, 2 drinks per day for men).

- Exercise regularly (at least 30 minutes a day) so that you burn at least as many calories as you consume to attain or maintain a healthy weight.

New Guidelines on Triglycerides and Heart Health

In 2011, the American Heart (AHA) emphasized in a scientific statement that diet and lifestyle changes are essential for patients with high triglyceride levels. Triglycerides are blood fats associated with unhealthy cholesterol levels and increased risk for heart disease. In addition to the standard advice on limiting saturated and trans fats, the AHA recommends that people with unhealthy triglyceride levels should:

- Limit fructose intake by consuming fruits that are relatively lower in fructose (cantaloupe, grapefruit, strawberries, peaches, bananas) and avoiding added sugars. Fructose is metabolized differently than other sugars and can significanty raise triglycerides.

- Avoid processed foods with added sugars of any kind. Pay attention to ingredients in food labels that indicate the presence of added sugars. These include terms such as sweeteners, syrups, fruit juice concentrates, molasses, and sugar molecules ending in “ose” (like dextrose and sucrose).

- Limit or avoid alcohol, especially if triglyceride levels exceed 500 mg/dL.

- Try to achieve a healthy weight! Weight loss has an enormous impact on decreasing triglycerides. A 5 – 10% weight loss can produce a 20% drop in triglyceride levels.

Introduction

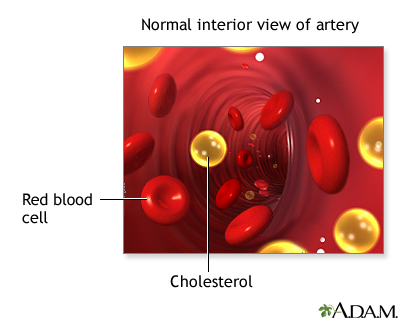

The goals of a heart-healthy diet are to eat foods that help obtain or maintain healthy levels of cholesterol and fatty molecules called lipids. You can achieve this by:

- Reducing overall cholesterol levels and low-density lipoproteins (LDL), which are harmful to the heart

- Increasing high-density lipoproteins (HDL), which are beneficial for the heart

- Reducing other harmful lipids (fatty molecules), such as triglycerides and lipoprotein(a)

Any diet should also help keep blood pressure and weight under control. It is also extremely important to limit daily salt (sodium) intake.

General Recommendations

The American Heart Association’s (AHA) current dietary and lifestyle guidelines recommend:

- Balance calorie intake and physical activity to achieve or maintain a healthy body weight. (Controlling weight, quitting smoking, and exercising regularly are essential companions of any diet program. Try to get at least 30 minutes, and preferably 45 - 60 minutes, of daily exercise.)

- Eat a diet rich in a variety of vegetables and fruits. Vegetables and fruits that are deeply colored (such as spinach, carrots, peaches, and berries) are especially recommended as they have the highest micronutrient content.

- Choose whole-grain and high-fiber foods. These include fruits, vegetables, and legumes (beans). Good whole grain choices include whole wheat, oats/oatmeal, rye, barley, brown rice, buckwheat, bulgur, millet, and quinoa.

- Eat fish, especially oily fish, at least twice a week (about 8 ounces/week). Oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, and sardines are rich in the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Consumption of these fatty acids is linked to reduced risk of sudden death and death from coronary artery disease.

- Get at least 5 - 10% of daily calories from omega-6 fatty acids, which are found in vegetable oils such as sunflower, safflower, corn, and soybean as well as nuts and seeds.

- Limit daily intake of saturated fat (found mostly in animal products) to less than 7% of total calories, trans fat (found in hydrogenated fats and oils, commercially baked products, and many fast foods) to less than 1% of total calories, and cholesterol (particularly in egg yolks, whole-fat dairy products, meat, and shellfish) to less than 300 mg per day. Choose lean meats and vegetable alternatives (such as soy). Select fat-free and low-fat dairy products. Grill, bake, or broil fish, meat, and skinless poultry.

- Use little or no salt in your foods. Reduce or avoid processed foods that are high in sodium (salt). Reducing salt can lower blood pressure and decrease the risk of heart disease and heart failure. We should all try to limit sodium intake to no more than 1,500 milligrams a day (less than ¾ teaspoon of salt).

- Cut down on beverages and foods that contain added sugars (corn syrups, sucrose, glucose, fructose, maltrose, dextrose, concentrated fruit juice, honey). The AHA recommends that women consume no more than 6 teaspoons (100 calories) of added sugar daily and that men consume no more than 9 teaspoons (150 calories).

- If you consume alcohol, do so in moderation. The AHA recommends limiting alcohol to no more than 2 drinks per day for men and 1 drink per day for women.

- People with existing heart disease should consider taking omega-3 fatty acid supplements (850 - 1,000 mg/day of EPA and DHA). For people with high triglyceride levels, higher doses (2 - 4 g/day) may be appropriate. The AHA recommends against taking antioxidant vitamin supplements (C, E, beta-carotene) or folic acid supplements for prevention of heart disease.

Women

Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding should avoid eating fish that is high in mercury content (shark, swordfish, mackerel, and tile fish). Choose fish and shellfish that are lower in mercury content and eat about 12 ounces/week. The AHA recommends a higher weekly fish amount for women than for men. However, women of childbearing age should limit tuna to 6 ounces a week to reduce the risks for mercury contamination.

Children

Atherosclerosis, the build-up of plaque in the arteries, begins in childhood. It is important for children and adolescents to adopt a heart-healthy diet to help prevent the development of heart disease later in life. Children should eat foods that are low in saturated fat, trans fat, and cholesterol. These foods include:

- Fruits and vegetables

- Whole grains

- Low-fat and nonfat dairy products

- Beans, fish, and lean meats

Increasing evidence suggests that vitamin D deficiencies in children and adolescents may be associated with high blood pressure, unhealthy cholesterol levels, and high blood sugar levels, which put patients at increased risk of heart disease, diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children and adolescents get a daily intake of at least 400 IU of vitamin D daily from food or supplement sources. [For more information, see “Vitamins” in Nutrition Basics section of this report.]

Nutrition Basics

Fats and Oils

Some fat is essential for normal body function. Fats can have good or bad effects on health, depending on their chemistry. The type of fat may be more important than the total amount of fat when it comes to reducing heart disease risk. Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) are “good” fats that help promote heart health, and should be the main type of fats consumed. Saturated fats and trans fats (trans fatty acids) are “bad” fats that can contribute to heart disease, and should be avoided or limited.

Current dietary guidelines for heart health recommend that:

- Total fat from all fat sources should be 25 - 35% of total daily calories.

- Monounsaturated fatty acids (found in olive oil, canola oil, peanut oil, nuts, and avocados) and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (found in oily fish, canola oil, flaxseed, and walnuts) should be the first choice for fats.

- Omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids (corn, safflower, sunflower, and soybean oils and nuts and seeds) are the second choice and should account for 5 - 10% of total calories as part of total fat intake. Linoleic acid, the main omega-6 fatty acid found in food, has anti-inflammatory properties. Higher intakes of omega-6 fatty acids may help lower blood pressure and reduce diabetes risk.

- Limit saturated fat (found predominantly in animal products, including meat and whole-fat dairy products, as well as coconut, palm kernel and palm oils, and cocoa butter) to less than 7% of total daily calories.

- Limit trans fats (found in stick margarine, commercial baked goods, snack and fried foods) to less than 1% of total calories.

All fats, good or bad, are high in calories compared to proteins and carbohydrates. In order to calculate daily fat intake, multiply the number of fat grams eaten by nine (one fat gram provides 9 calories, whether it's oil or fat) and divide by the number of total daily calories desired. One teaspoon of oil, butter, or other fats provides about 5 grams of fat. All fats, no matter what source they are from, add the same calories. The American Heart Association recommends choosing fats and oils that have less than 2 grams of saturated fat per tablespoon.

Try to replace saturated fats and trans fatty acids with unsaturated fats from plant and fish oils. Omega-3 fatty acids, which are found in fish and some plant sources, are a good source of unsaturated fats. Generally, two servings of fish per week provide a healthful amount of omega-3 fatty acids.

Fish oil dietary supplements are another option. Fish and fish oil supplements contain docasahexaenoic (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic (EPA) acids, which have significant benefits for the heart. Patients with heart disease, heart failure, or those who need to lower triglyceride levels may in particular benefit from fish oil supplements, provided under a doctor’s consultation.

Fat Substitutes. Fat substitutes added to commercial foods or used in baking, deliver some of the desirable qualities of fat, but they do not add as many calories. They cannot be eaten in unlimited amounts. They are considered most useful for helping keep down total calorie count.

- Plants substances known as sterols, and their derivatives called stanols, reduce cholesterol by blocking its absorption in the intestinal tract. Margarines containing sterols are available.

- Olestra (Olean) passes through the body without leaving behind any calories from fat. However, it can cause cramps and diarrhea, and even small amounts of olestra may deplete the body of certain vitamins and nutrients.

A number of other fat-replacers are also available. Although studies to date have not shown any significant adverse health effects, their effect on weight control is uncertain, since many of the products containing them may be high in sugar. People who learn to cook using foods naturally lacking or low in fat eventually lose their taste for high-fat diets, something that may not be true for those using fat substitutes.

Carbohydrates, Fiber, and Sugar

Carbohydrates are either complex (as in starches) or simple (as in sugars). One gram of carbohydrates provides four calories. The current general recommendation is that carbohydrates should provide 50 - 60% of the daily caloric intake. Many studies report that people can protect their heart and circulation by eating plenty of fruits and vegetables.

Complex Carbohydrates (Fiber). Complex carbohydrates found in whole grains and vegetables are preferred over those found in starch-heavy foods, such as pastas, white-flour products, and white potatoes. Most complex carbohydrates are high in fiber, which is important for health. Whole grains are extremely important for people with diabetes or those at risk for it.

Dietary fiber is an important component of many complex carbohydrates. It is found only in plants. Fiber cannot be digested by humans but passes through the intestines, drawing water with it, and is eliminated as part of feces content. The recommended daily intake of dietary fiber for heart protection is at least 25 grams for women and 38 grams for men ages 19 to 50. Older women and men need at least 21 and 30 grams of fiber, respectively.

Different fiber types may have specific benefits:

- Insoluble fiber (found in wheat bran, whole grains, seeds, nuts, legumes, and fruits and vegetables) may help achieve weight loss. Consuming whole grains on a regular basis may lower the risk for heart disease and heart failure, improve factors involved with diabetes, and lower the risk for type 2 diabetes. High consumption of nuts (such as almonds, macadamia, and walnuts) may be highly heart protective, independent of their fiber content.

- Soluble fiber (found in dried beans, oat bran, barley, apples, and citrus fruits) may help achieve healthy cholesterol levels and possibly reduce blood pressure as well.

- Soluble fiber supplements, such as those that contain psyllium or glucomannan, may also be beneficial. Psyllium is taken from the husk of a seed and is very effective for lowering total and LDL cholesterol. It is found in laxatives (Metamucil), breakfast cereals, and other products. People who increase intake of soluble fiber should also drink more water to avoid cramps.

Simple Carbohydrates (Sugar). Doctors recommend that no more than 10% of daily calories should come from sugar. (Currently, Americans eat nearly half a pound of sugar a day on average, and sugar intake constitutes 25% of a day's calories.) Sugars are usually one of two types:

- Sucrose. Source of most dietary sugar, found in sugar cane, honey, and corn syrup.

- Fructose. Found in fruits and vegetables. Although fructose does not appear to be have any different effects in the body than sucrose, most of the fruits and vegetables that contain it are important for good health. However, because fructose can raise triglyceride levels, people with high triglycerides should try to select fruits that are relatively lower in fructose (canataloupe, grapefruit, strawberries, peaches, and bananas).

- A third sugar, lactose, is a naturally occurring sugar found in dairy products including yogurt and cheese.

High levels of sugar consumption -- whether fructose or sucrose -- are associated with higher triglycerides and lower levels of HDL cholesterol, the so-called good cholesterol. The high consumption of sugar is contributing to our current obesity epidemic. Soda, other sweetened beverages, and fruit juice are major causes of childhood obesity.

The American Heart Association recommends eating nutrient-rich fruits and vegetables instead of sugar-sweetened beverages and food products with added sugars. Women should consume no more than 6 teaspoons (100 calories) of added sugar daily and men no more than 9 teaspoons (150 calories).

Be aware that nutrition labels on food packages do not distinguish between added sugar and naturally occurring sugar. Ingredients that indicate added sugars include corn sweetener, corn sugar, high fructose corn syrup, fruit juice concentrates, honey, molasses, and any sugar molecules ending in “ose” (dextrose, fructose, glucose, lactose, maltose, sucrose).

Protein

Protein is found in animal-based products (meat, poultry, fish, and dairy) as well as vegetable sources such as beans, soy, nuts, and whole grains. In general, doctors recommend that proteins should provide 12 - 20% of daily calories. One gram of protein contains four calories. Protein is important for strong muscles and bones. The best sources of protein are fish, poultry, and soy. Restrict intake of red meat or any meat that is not lean.

Dietary Cholesterol. Animal-based protein contains dietary cholesterol. High amounts of dietary cholesterol occur in meat, whole fat dairy products, egg yolks, and shellfish. (Plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, nuts, grains, do not contain cholesterol.) The American Heart Association recommends no more than 300 mg of dietary cholesterol per day for the general population and no more than 200 mg daily for those with high cholesterol or heart disease.

Fish. Fish is probably the best source of protein. Evidence suggests that eating moderate amounts of fish (twice a week) may improve triglyceride and HDL levels and help lower the risks for death from heart disease, dangerous heart rhythms, blood pressure, a tendency for blood clots, and the risk for stroke.

The most healthy fish are oily fish such as salmon, mackerel, trout, sardines, or albacore ("white") tuna, which are high in omega-3 fatty acids. On average, three capsules of fish oil (preferably as supplements of DHA-EPA) are about equivalent to eating one serving of fish.

Most guidelines recommend eating fish at least twice a week. Doctors may recommend that people with heart disease or high triglyceride levels consume extra quantities or take DHA-EPA supplements. Target goals for DHA-EPA consumption are at least 500 mg/day for people without clinical signs of heart disease and 800 - 1,000 mg/day for people with heart disease or heart failure.

Women of childbearing age or nursing mothers should avoid fish that contains high amounts of mercury (such as shark, swordfish, golden bass, and king mackerel) and limit intake of tuna to 6 ounces/week. They should, however, try to eat at least 12 ounces/week of a variety of lower mercury-containing fish and shellfish (such as catfish, salmon, haddock, perch, tilapia, trout, crab, shrimp, and scallops). Most doctors agree that the benefits of fish intake (especially from low-mercury fish) outweigh the potential risks.

Soy. Soy is an excellent food. It is rich in both soluble and insoluble fiber, omega-3 fatty acids, and provides all essential proteins. Soy proteins have more vitamins and minerals than meat or dairy proteins. They also contain polyunsaturated fats, which are better than the saturated fat found in meat. The best sources of soy protein are soy products (such as tofu, soy milk, and soybeans). Soy sauce is not a good source. It contains only a trace amount of soy and is very high in sodium.

For many years, soy was promoted as a food that could help lower cholesterol and improve heart disease risk factors. But an important review of studies found that soy protein and isoflavone supplement pills do not have a major effect on cholesterol or heart disease prevention. The American Heart Association still encourages patients to include soy foods as part of an overall heart healthy diet but does not recommend using isoflavone supplements.

Meat and Poultry. For heart protection, choose lean meat. Saturated fat in meat is the primary danger to the heart. The fat content of meat varies depending on the type and cut. It is best to eat skinless chicken or turkey. The leanest cuts of pork (loin and tenderloin), veal, and beef are nearly comparable to chicken in calories and fat as well as their effect on LDL and HDL levels. However, in terms of heart health, fish or beans are better choices.

Dairy Products. The best dairy choices are low-fat or fat-free products. Substituting low-fat dairy products can help lower blood pressure and lower the incidence of factors related to type 2 diabetes and heart disease (insulin resistance, high blood pressure, and unhealthy cholesterol).

Vitamins

Antioxidant Vitamins. Vitamins E and C have been studied for their health effects because they serve as antioxidants. Antioxidants are chemicals that act as scavengers of particles known as oxygen-free radicals (also sometimes called oxidants). High intake of foods rich in these vitamins (as well as other food chemicals) have been associated with many health benefits, including prevention of heart problems.

Although some older research initially observed favorable effects from vitamin E in preventing blood clots and preventing build-up of plaque on blood vessel walls, many recent studies have found no heart protection from either vitamin E or C supplements. Supplements of vitamin E, vitamin C, and beta-carotene are not recommended.

B Vitamins (Folic Acid). Deficiencies in the B vitamins folate (known also as folic acid), B6, and B12 have been associated with a higher risk for heart disease in some studies. Such deficiencies produce higher blood levels of homocysteine, an amino acid that has been associated with a higher risk for heart disease, stroke, and heart failure.

While major studies have indicated that B vitamin supplements help lower homocysteine levels, they do not protect against heart disease, stroke, or dementia (memory loss). Some researchers think that homocysteine may be a marker for heart disease rather than a cause of it.

Vitamin D. Vitamin D, in addition to promoting bone health, may also be important for heart health. In studies, people who were vitamin D deficient appeared to have an increased risk for heart-related deaths. Other studies have suggested that children and adolescents who have low blood levels of vitamin D may be at increased risk of developing heart disease and diabetes. More research is needed.

Dietary sources of vitamin D include fatty fish (such as salmon, mackerel, and tuna), egg yolks, liver, and vitamin D-fortified milk, orange juice, or cereals. Sunlight is also an important source of vitamin D. However, many Americans do not get enough vitamin D solely from diet or exposure to sunlight and may require supplements.

At this time, there is no standard recommendation for whether people should take vitamin D supplements for heart health, or at what dosages. Many doctors recommend that for bone and overall health, children and teenagers should get at least 400 IU of vitamin D daily, adults under age 50 should get 400 - 800 IU daily, and adults over age 50 should get 800 - 1,000 IU daily.

Minerals

Potassium. A potassium-rich diet can provide a small reduction in blood pressure. Potassium-rich foods include bananas, oranges, pears, prunes, cantaloupes, tomatoes, dried peas and beans, nuts, potatoes, and avocados. Potassium supplements should not be taken by patients without checking with your doctor first. For those using potassium-sparing diuretics (such as spironolactone), or have chronic kidney problems, potassium supplements may be very dangerous.

Magnesium. Some studies suggest that magnesium supplements may cause small but significant reductions in blood pressure. The recommended daily allowance of magnesium is 320 mg. People who live in soft water areas, who use diuretics, or who have other risk factors for magnesium loss may require more dietary magnesium than others.

Calcium. Calcium regulates the tone of the smooth muscles lining blood vessels. Studies have found that people who consume enough dietary calcium on a daily basis have lower blood pressure than those who do not. The effects of extra calcium on blood pressure, however, are mixed, with some studies showing higher pressure with calcium supplementation. Studies have indicated that calcium supplements do not prevent heart disease and some controversial reports suggest that they might even increase risk.

Salt Restriction

Some sodium (salt) is necessary for health, but the amount is vastly lower than that found in the average American diet. High salt intake is associated with high blood pressure (hypertension). Everyone should restrict their sodium intake to less than 1,500 mg a day. This is particularly important for people over age 50, those who have high blood pressure, and African-Americans. Limiting sodium can help lower blood pressure and may also help protect against heart failure and heart disease.

Some people (especially African-Americans, older adults, people with diabetes, and people with a family history of hypertension) are “salt sensitive,” which means their blood pressure responds much more to salt than other people. People with salt sensitivity have a higher than average risk of developing high blood pressure as well as other heart problems

Simply eliminating the use of salt at the table eating can help. But it is also important to reduce or avoid processed and prepared foods that are high in sodium. Spices can be used in place of salt to enhance flavor.

Salt substitutes, such as Nusalt and Mrs. Dash (which contain mixtures of potassium, sodium, and magnesium), are available, but they can be risky for people with kidney disease or those who take blood pressure medication that causes potassium retention. For people without risks for potassium excess, adding potassium-rich foods to a diet can help.

Here are some tips to lower your sodium (salt) intake:

- Look for foods that are labeled “low-sodium,” “sodium-free,” “no salt added,” or “unsalted.” Check the total sodium content on food labels. Be especially careful of canned, packaged, and frozen foods. A nutritionist can teach you how to understand these labels.

- Don’t cook with salt or add salt to your food. Try pepper, garlic, lemon, or other spices for flavor instead. Be careful of packaged spice blends as these often contain salt or salt products (like monosodium glutamate, or MSG).

- Avoid processed meats (particularly cured meats, bacon, hot dogs, sausage, bologna, ham, and salami). Processed meats have been associated with increased risk for heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and an increased death rate.

- Avoid foods that are naturally high in sodium, like anchovies, nuts, olives, pickles, sauerkraut, soy and Worcestershire sauces, tomato and other vegetable juices, and cheese.

- Take care when eating out. Stick to steamed, grilled, baked, boiled, and broiled foods with no added salt, sauce, or cheese.

- Use oil and vinegar, rather than bottled dressings, on salads.

- Eat fresh fruit or sorbet when having dessert.

Fluids

Water. People with certain medical conditions, (such as heart failure), that cause fluid retention may need to restrict their intake of water and other fluids.

Alcohol. A number of studies have found heart protection from moderate alcohol intake (one or two glasses a day). The benefits reported include higher HDL levels, blood clot prevention, and anti-inflammatory properties plus lower rates of heart failure and heart attack. Although red wine is most often cited for healthful properties, any type of alcoholic beverage appears to have similar benefit.

However, alcohol abuse can increase the risk of high blood pressure and many other serious problems. Men should limit their intake to an average of no more than one or two drinks a day, and women (especially those at risk for breast cancer) and thinner people should only have one drink a day. (A “drink” is equivalent to a 12-ounce bottle of beer, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or a 1.5-ounce shot of hard liquor.)

Overuse of alcohol can also lead to many heart problems. People with high triglyceride levels should drink sparingly if at all because even small amounts of alcohol can significantly increase blood triglycerides. Pregnant women, people who can't drink moderately, and people with liver disease should not drink at all. People who are watching their weight should be aware that alcoholic beverages are very high in calories.

Coffee and Tea. Coffee drinking is associated with small increases in blood pressure, but the risk it poses is very small in people with normal blood pressure. Moderate coffee consumption (1 - 2 cups a day) poses no heart risks and long-term coffee consumption does not appear to increase the risk for heart disease in most people, even if they consume large daily amounts.

Although both black and green tea contain caffeine, they are safe for the heart. Tea contains chemicals called flavonoids that may be heart protective.

Diet Plans

Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet is rich in heart-healthy fiber and nutrients, including omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants. The diet consists of fruits, vegetables, and unsaturated “good” fats, particularly olive oil. Olive oil has been associated with lower blood pressure, a lower risk for heart disease, and possible benefits for people with type 2 diabetes. Researchers think that the main health benefit of olive oil is oleic acid, which is a type of monounsaturated fatty acid. Olive oil also contains polyphenols, which are phytochemicals that contain antioxidant properties. Virgin olive oil, which comes from the first pressing of olives, contains a higher polyphenol content than refined olive oil, which comes from later pressings.

There are several variations to the Mediterranean diet, but general recommendations include:

- Limit red meats.

- Drink one or two glasses of wine each day if alcohol is enjoyable and there are no reasons to restrict its use.

- Limit whole fat dairy products.

- Eat moderate amounts of fish and poultry. Fish is the diet’s main protein source.

- Eat plenty of fresh fruits and vegetables, nuts, legumes, beans, and whole grains.

- Season foods with garlic, onions, and herbs.

- Use virgin olive oil.

Even though fats make up about 40% of the calories found in the traditional Mediterranean diet, they are mostly unsaturated. Growing evidence continues to support the heart-protective properties of the Mediterranean diet. Research has shown that such a diet prevents heart disease, reduces the risk for a second heart attack and helps cholesterol-lowering statin drugs work better. (Despite claims, garlic does not help lower LDL "bad "cholesterol, though it adds flavor to many Mediterranean recipes.)

Seniors who combine a Mediterranean diet with healthy lifestyle habits have been found to live longer lives. Many doctors regard the Mediterranean diet to be as good as the American Heart Association low-fat diet for preventing recurrence of heart attack, stroke, or other heart events.

Premenopausal women on the diet should eat foods rich in iron or vitamin C, which aids in iron absorption. Women should also ask their doctor if they need a calcium supplement because they consume fewer dairy products. People should avoid wine if they have risk factors for complications from alcohol. Such people include women who are pregnant or at risk for breast cancer and anyone prone to alcohol abuse.

DASH Diet

The salt-restrictive DASH diet (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) is proven to help lower blood pressure, and may have additional benefits for preventing heart disease, stroke, and heart failure. Effects on blood pressure are sometimes seen within a few weeks. This diet is rich in important nutrients and fiber. It also provides far more potassium (4,700 mg/day), calcium (1,250 mg/day), and magnesium (500 mg/day) -- but much less sodium -- than the average American diet.

DASH diet recommendations:

- Limit sodium (salt) intake to no more than 2,300 mg a day (a maximum intake of 1,500 mg a day is a much better goal and is now endorsed by the American Heart Association).

- Reduce saturated fat to no more than 6% of daily calories and total fat to 27% of daily calories. (But, include calcium-rich dairy products that are non- or low-fat.)

- When choosing fats, select monounsaturated oils, such as olive or canola oils.

- Choose whole grains over white flour or pasta products.

- Choose fresh fruits and vegetables every day. Many of these foods are rich in potassium, fiber, or both, which may help lower blood pressure.

- Include nuts, seeds, or legumes (dried beans or peas) daily.

- Choose modest amounts of protein (no more than 18% of total daily calories). Fish, skinless poultry, and soy products are the best protein sources.

- Other daily nutrient goals in the DASH diet include limiting carbohydrates to 55% of daily calories and dietary cholesterol to 150 mg. Patients should try to get at least 30 g of daily fiber.

Low Carbohydrate Diets

Low carbohydrate diets generally restrict the amount of carbohydrates but do not restrict protein sources.

The Atkins diet restricts complex carbohydrates in vegetables and, particularly, fruits that are known to protect against heart disease. The Atkins diet also can cause excessive calcium excretion in urine, which increases the risk for kidney stones and osteoporosis.

Low-carb diets, such as South Beach, The Zone, and Sugar Busters, rely on a concept called the "glycemic index," or GI, which ranks foods by how fast and how high they cause blood sugar levels to rise. Foods on the lowest end of the index take longer to digest. Slow digestion wards off hunger pains. It also helps stabilize insulin levels. Foods high on the glycemic index include bread, white potatoes, and pasta, while low-glycemic foods include whole grains, fruit, lentils, and soybeans.

There has been debate about whether Atkins and other low-carbohydrate diets can increase the risk for heart disease, as people who follow these diets tend to eat more animal-saturated fat and protein and less fruits and vegetables. In general, these diets appear to lower triglyceride levels and raise HDL (“good”) cholesterol levels. Total cholesterol and LDL (“bad”) cholesterol levels tend to remain stable or possibly increase somewhat. However, large studies have not found an increased risk for heart disease, at least in the short term. In fact, some studies indicate that these diets may help lower blood pressure.

Low-carbohydrate diets help with weight loss in the short term, possibly better than diets that allow normal amounts of carbohydrates and restrict fats. However, overall, there is not good evidence showing long-term efficacy for these diets. Likewise, long-term safety and other possible health effects are still a concern, especially since these diets restrict healthy foods such as fruit, vegetables, and grains while not restricting saturated fats.

Low-Fat Diets

Dietary guidelines recommend keeping total fat intake to 20 - 30% of total daily calories, with saturated fat less than 10% of calories. Very low-fat diets generally restrict fat intake to 20% or less of total daily calories. The Ornish program, recommended for some heart disease patients, limits fats even more drastically. It aims to reduce saturated fats as much as possible, restricting total fat to 10%, and increasing carbohydrates to 75% of calories.

The Ornish program is a very demanding regimen:

- It excludes all oils and animal products except nonfat yogurt, nonfat milk, and egg whites.

- It emphasizes whole grains, legumes, and fresh fruits and vegetables.

- People in the program exercise for 90 minutes at least three times a week.

- Stress reduction techniques are used.

- People do not smoke or drink more than two ounces of alcohol per day.

Benefits of Low-Fat Diets. Low-fat programs may help keep weight off. Low-fat diets that are high in fiber, whole grains, legumes, and fresh produce offer health advantages in addition to their effects on cholesterol. These foods are also lower on the glycemic index than high-glycemic foods, such as bread, potatoes, and pasta. Lowering the glycemic index (by, for example, cutting down on starchy vegetables and replacing pasta with whole grains) may help increase weight loss and heart benefits for high-carbohydrate diets.

While claims regarding a significant reduction in angina and even reduction in coronary artery stenosis have been made by the Ornish program directors, actual regression in atherosclerosis or prevention of heart disease has only been shown in a small number of patients.

Concerns Regarding Low-Fat Diets. The American Heart Association notes that the Ornish program is so difficult to maintain that most people have difficulty staying with it. Very low-fat diets reduce HDL ("good") cholesterol levels. These diets may also reduce calcium absorption, which can be harmful for women at risk for osteoporosis. Many people who reduce their fat intake do not consume enough of the basic nutrients, including vitamins A, D, E, calcium, iron, and zinc. People on low-fat diets should eat a wide variety of foods and take a multivitamin if appropriate.

Calorie Restriction

Calorie restriction has been the cornerstone of weight-loss programs. Restricting calories also appears to have beneficial effects on cholesterol levels, including reducing LDL and triglycerides and increasing HDL levels. A 5 – 10% decrease in body weight can result in a 20% decrease in triglyceride levels. In general, reducing calories and increasing exercise is still the best method for maintaining weight loss and preventing serious conditions, notably diabetes.

The standard dietary recommendations for losing weight are:

- As a rough rule of thumb, one pound of fat contains about 3,500 calories, so one could lose a pound a week by reducing daily caloric intake by about 500 calories a day. The more severe the daily calorie restriction, the faster the weight loss.

- To determine the daily calorie requirements for specific individuals, multiply the number of pounds of ideal weight by 12 - 15 calories. The number of calories depends on gender, age, and activity levels. For example, a 50-year old woman who wants to maintain a weight of 135 pounds and is mildly active might require only 12 calories per pound (1,620 calories a day). A 25-year-old female athlete who wants to maintain the same weight might require 25 calories per pound 2,025 (calories a day).

- Fat intake should be no more than 30% of total calories. Most fats should be in the form of monounsaturated fats (such as olive oil). Avoid saturated fats (found in animal products).

Lifestyle Changes

Guidelines for Weight Loss

Lifelong changes in eating habits, physical activity, and attitudes about food and weight are essential to weight management. Unfortunately, although many people can lose weight initially, it is very difficult to maintain weight loss. People with type 2 diabetes may have a particularly difficult time. Here are some general suggestions that may be helpful:

- Start with realistic goals. When overweight people achieve even modest weight loss they reduce risk factors in the heart. Ideally, overweight patients should strive for 15% weight loss or better, particularly people with type 2 diabetes.

- A regular exercise program is essential for maintaining weight loss. If there are no health prohibitions, choose one that is enjoyable. Check with a doctor about any health consideration.

- Do not take hunger pangs as cues to eat. A stomach that has been stretched by large meals will continue to signal hunger for large amounts of food until its size reduces over time with smaller meals.

- Be honest about how much you eat, and track calories carefully. Studies on weight control that depend on self-reporting of food intake frequently reveal that subjects badly misjudge how much they eat (typically underestimating high-calorie foods and overestimating low-calorie foods). In one study, even dietitians underreported their calorie intake by 10%. People who do not carefully note everything they eat tend to take in excessive calories when they believe they are dieting.

- For patients who cannot lose weight with diet alone, weight-loss medications may be worth considering. Orlistat (Xenical in prescription form, alli in non-prescription form) produces only modest weight loss and may cause diarrhea, but it may help improve cholesterol levels.

- Once a person has lost weight, maintenance is required. To maintain a healthy weight, make careful decisions about how many calories you consume in food and how many calories you expend through physical activity. Such thinking will eventually become automatic.

- For severely obese patients, weight loss through bariatric surgery may be an option.

Even repeated weight loss failure is no reason to give up.

Exercise

Inactivity is a major risk factor for coronary artery disease, on par with smoking, unhealthy cholesterol, and high blood pressure. In fact, studies suggest that people who change their diet in order to control cholesterol lower their risk for heart disease only when they also follow a regular aerobic exercise program.

Research strongly supports the benefits of exercise on coronary artery disease:

- People who maintain an active lifestyle have a 45% lower risk of developing heart disease than do sedentary people. Even moderate exercise reduces the risk of heart attack.

- People who lose weight and exercise regularly have a significantly better chance of maintaining weight loss compared to those who do not exercise.

- Burning at least 250 calories a day (the equivalent of about 45 minutes of brisk walking or 25 minutes of jogging) appears to offer the greatest protection against coronary artery disease, particularly by raising HDL ("good" cholesterol) levels.

- Aerobic exercise also appears to open up the blood vessels and, in combination with a healthy diet, may improve blood-clotting factors.

- Resistance (weight) training offers a complementary benefit by reducing LDL (the so-called bad cholesterol) levels.

- Exercises that train and strengthen the chest muscles may be very important for patients with angina.

Resources

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov -- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- www.eatright.org -- American Dietetic Association

- www.heart.org -- American Heart Association

- www.acc.org -- American College of Cardiology

- http://fnic.nal.usda.gov -- Food and Nutrition Information Center

References

American Heart Association Nutrition Committee; Lichtenstein AH, Appel LJ, Brands M, Carnethon M, Daniels S, et al. Diet and lifestyle recommendations revision 2006: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee. Circulation. 2006 Jul 4;114(1):82-96.

Appel LJ, Frohlich ED, Hall JE, Pearson TA, Sacco RL, Seals DR, et al. The importance of population-wide sodium reduction as a means to prevent cardiovascular disease and stroke: a call to action from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 Mar 15;123(10):1138-43. Epub 2011 Jan 13.

Bazzano LA, Reynolds K, Holder KN, He J. Effect of folic acid supplementation on risk of cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2006 Dec 13;296(22):2720-6.

Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, et al. A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women's Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Aug 13-27;167(15):1610-8.

Forman JP, Stampfer MJ, Curhan GC. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women. JAMA. 2009 Jul 22;302(4):401-11.

Fung TT, Chiuve SE, McCullough ML, Rexrode KM, Logroscino G, Hu FB. Adherence to a DASH-style diet and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke in women. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Apr 14;168(7):713-20.

Gardner CD, Kiazand A, Alhassan S, Kim S, Stafford RS, Balise RR, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among overweight premenopausal women: the A TO Z Weight Loss Study: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007 Mar 7;297(9):969-77.

Gidding SS, Lichtenstein AH, Faith MS, Karpyn A, Mennella JA, Popkin B, Rowe J, Van Horn L, Whitsel L. Implementing American Heart Association pediatric and adult nutrition guidelines: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Nutrition Committee of the council on nutrition, physical activity and metabolism, council on cardiovascular disease in the young, council on arteriosclerosis, thrombosis and vascular biology, council on cardiovascular nursing, council on epidemiology and prevention, and council for high blood pressure research. Circulation. 2009 Mar 3;119(8):1161-75.

GISSI-HF Investigators, Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP, Marchioli R, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, et al. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008 Oct 4;372(9645):1223-30. Epub 2008 Aug 29.

Harris WS, Mozaffarian D, Rimm E, Kris-Etherton P, Rudel LL, Appel LJ, Engler MM, Engler MB, Sacks F. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2009 Feb 17;119(6):902-7. Epub 2009 Jan 26.

Johnson RK, Appel LJ, Brands M, Howard BV, Lefevre M, Lustig RH, et al. Dietary sugars intake and cardiovascular health: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009 Sep 15;120(11):1011-20. Epub 2009 Aug 24.

Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Mehra MR, Ventura HO. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Aug 11;54(7):585-94.

McMillan-Price J, Petocz P, Atkinson F, O'Neill K, Samman S, Steinbeck K,et al. Comparison of 4 diets of varying glycemic load on weight loss and cardiovascular risk reduction in overweight and obese young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006 Jul 24;166(14):1466-75.

Mente A, de Koning L, Shannon HS, Anand SS. A systematic review of the evidence supporting a causal link between dietary factors and coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Apr 13;169(7):659-69.

Micha R, Wallace SK, Mozaffarian D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2010 Jun 1;121(21):2271-83. Epub 2010 May 17.

Miller M, Stone NJ, Ballantyne C, Bittner V, Criqui MH, Ginsberg HN, et al. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 May 24;123(20):2292-333. Epub 2011 Apr 18.

Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Effectiveness-Based Guidelines for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Women -- 2011 Update: A Guideline From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011 Feb 16. [Epub ahead of print]

Mozaffarian D. Nutrition and cardiovascular disease. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, eds. Brunow: Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Saunders; 2012:chap 48.

Nordmann AJ, Suter-Zimmermann K, Bucher HC, Shai I, Tuttle KR, Estruch R, et al. Meta-analysis comparing Mediterranean to low-fat diets for modification of cardiovascular risk factors. Am J Med. 2011 Sep;124(9):841-51.e2.

Pan A, Sun Q, Bernstein AM, Schulze MB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Red meat consumption and mortality: results from 2 prospective cohort studies. Arch Intern Med. 2012 Mar 12. [Epub ahead of print]

Pittas AG, Chung M, Trikalinos T, Mitri J, Brendel M, Patel K, et al. Systematic review: Vitamin D and cardiometabolic outcomes. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Mar 2;152(5):307-314.

Reis JP, von Mühlen D, Miller ER 3rd, Michos ED, Appel LJ. Vitamin D status and cardiometabolic risk factors in the United States adolescent population. Pediatrics. 2009 Aug 3. [Epub ahead of print]

Sabaté J, Oda K, Ros E. Nut consumption and blood lipid levels: a pooled analysis of 25 intervention trials. Arch Intern Med. 2010 May 10;170(9):821-7.

Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008 Nov 12;300(18):2123-33. Epub 2008 Nov 9.

Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul 17;359(3):229-41.

Slavin JL. Position of the American Dietetic Association: health implications of dietary fiber. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008 Oct;108(10):1716-31.

Trichopoulou A, Bamia C, Trichopoulos D. Anatomy of health effects of Mediterranean diet: Greek EPIC prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009 Jun 23;338:b2337. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2337.

U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7th Edition, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, December 2010.

Wang L, Manson JE, Song Y, Sesso HD. Systematic Review: Vitamin D and calcium supplementation in prevention of cardiovascular events. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Mar 2;152(5):315-323.

White B. Dietary fatty acids. Am Fam Physician. 2009 Aug 15;80(4):345-50.

Yang Q, Cogswell ME, Flanders WD, Hong Y, Zhang Z, Loustalot F, et al. Trends in cardiovascular health metrics and associations with all-cause and CVD mortality among US adults. JAMA. 2012 Mar 28;307(12):1273-83. Epub 2012 Mar 16.

|

Review Date:

5/22/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |