Heart failure

Highlights

Heart Failure

Heart failure is a condition in which the heart does not pump enough blood to meet the needs of the body’s tissues. Heart failure can develop slowly over time as the result of other conditions (such as high blood pressure and coronary artery disease) that weaken the heart. It can also occur suddenly as the result of damage to the heart muscle.

Symptoms

Common signs and symptoms of heart failure include:

- Fatigue

- Shortness of breath

- Wheezing or cough

- Fluid retention and weight gain

- Loss of appetite

- Abnormally fast or slow heart rate

Treatment

Treatment for heart failure depends on its severity. All patients need dietary salt restriction and other lifestyle adjustments, medication, and monitoring. Patients with very weakened hearts may need implanted devices (such as pacemakers, implantable cardiac defibrillators, or devices that help the heart pump blood) or surgery, including heart transplantation.

Doctors usually treat heart failure, and the underlying conditions that cause it, with a combination of medications. These medications include:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Beta blockers

- Diuretics

- Aldosterone blockers

- Digitalis

- Hydralazine or nitrates

Other medications that may be helpful include:

- Statins

- Aspirin and warfarin

Decision Making in Advanced Heart Failure

For patients with advanced heart failure, symptom relief, quality of life, and personal values are as important to consider as survival, according to a 2012 scientific statement from the American Heart Association (AHA). The AHA notes that while technology has increased the treatment options for advanced heart failure, “doing everything is not always the right thing.” The guidelines emphasize a patient-centered approach to treatment and the importance of patients discussing with their doctors their preferences, expectations, and goals.

Introduction

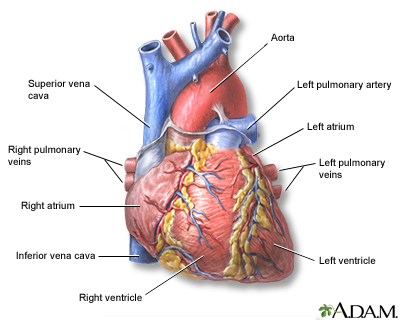

Heart failure is a condition in which the heart does not pump enough blood to meet the needs of the body’s tissues. To understand what occurs in heart failure, it helps to be familiar with the anatomy of the heart and how it works. The heart is composed of two independent pumping systems, one on the right side, and the other on the left. Each has two chambers, an atrium and a ventricle. The ventricles are the major pumps in the heart.

The Right Side of the Heart. The right system receives blood from the veins of the whole body. This is "used" blood, which is poor in oxygen and rich in carbon dioxide.

- The right atrium is the first chamber that receives blood.

- The chamber expands as its muscles relax to fill with blood that has returned from the body.

- The blood enters a second muscular chamber called the right ventricle.

- The right ventricle is one of the heart's two major pumps. Its function is to pump the blood into the lungs.

- The lungs restore oxygen to the blood and exchange it with carbon dioxide, which is exhaled.

The Left Side of the Heart. The left system receives blood from the lungs. This blood is now rich in oxygen.

- The oxygen-rich blood returns through veins coming from the lungs (pulmonary veins) to the heart.

- The heart receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs in the left atrium, the first chamber on the left side.

- Here, it moves to the left ventricle, a powerful muscular chamber that pumps the blood back out to the body.

- The left ventricle is the strongest of the heart's pumps. Its thicker muscles need to perform contractions powerful enough to force the blood to all parts of the body.

- This strong contraction produces systolic blood pressure (the first and higher number in blood pressure measurement). The lower number (diastolic blood pressure) is measured when the left ventricle relaxes to refill with blood between beats.

- Blood leaves the heart through the aorta, the major artery that feeds blood to the entire body.

The Valves. Valves are muscular flaps that open and close so blood will flow in the right direction. There are four valves in the heart:

- The tricuspid regulates blood flow between the right atrium and the right ventricle.

- The pulmonary valve opens to allow blood to flow from the right ventricle to the lungs.

- The mitral valve regulates blood flow between the left atrium and the left ventricle.

- The aortic valve allows blood to flow from the left ventricle to the aorta.

The Heart's Electrical System. The heartbeats are triggered and regulated by the conducting system, a network of specialized muscle cells that form an independent electrical system in the heart muscles. These cells are connected by channels that pass chemically-triggered electrical impulses.

Description of Heart Failure

Heart failure is a process, not a disease. The heart doesn't "fail" in the sense of ceasing to beat (as occurs during cardiac arrest). Rather, it weakens, usually over the course of months or years, so that it is unable to pump out all the blood that enters its chambers. As a result, fluids tend to build up in the lungs and tissues, causing congestion. This is why heart failure is also sometimes referred to as "congestive heart failure."

Ways the Heart Can Fail. Heart failure can occur in several ways:

- The muscles of the heart pumps (ventricles) become thin and weakened. They stretch (dilate) and cannot pump the blood with enough force to reach all the body's tissues.

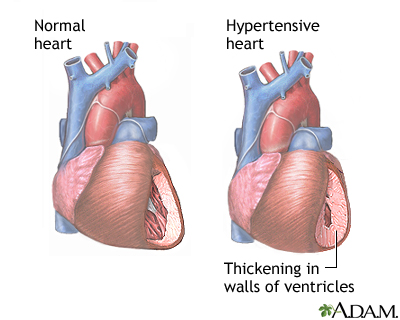

- The heart muscles stiffen or thicken. They lose elasticity and cannot relax. Insufficient blood enters the chamber, so not enough blood is pumped out into the body to serve its needs.

- Sometimes the valves of the heart are abnormal. (Valves open or close to control the flow of blood entering or leaving the heart). They may narrow, such as in aortic stenosis, causing a back up of blood, or they may close improperly so that blood leaks back into the heart. The mitral valve (which regulates blood flow between the two chambers on the left side of the heart) often becomes leaky in severe heart failure -- a condition called mitral regurgitation.

- The very mechanisms that the body uses to compensate for inefficient heart pumping can, over time, change the architecture of the heart (called remodeling) and finally lead to irreversible problems.

The specific effects of heart failure on the body depend on whether it occurs on the left or right sides of the heart. Over time, however, in either form of heart failure, the organs in the body do not receive enough oxygen and nutrients, and the body's wastes are removed slowly. Eventually, vital systems break down.

Failure on the Left Side (Left-Ventricular Heart Failure). Failure on the left side of the heart is more common than failure on the right side. The failure can be a result of abnormal systolic (contraction) or diastolic (relaxation) action:

- Systolic. Systolic heart failure is a pumping problem. In systolic failure, the heart muscles weaken and cannot pump enough blood throughout the body. The left ventricle is usually stretched (dilated). Fluid backs up and accumulates in the lungs (pulmonary edema). Systolic heart failure typically occurs in men between the ages of 50 - 70 years who have had a heart attack.

- Diastolic. Diastolic heart failure is a filling problem. When the left ventricle muscle becomes stiff and cannot relax properly between heartbeats, the heart cannot fill fully with blood. When this happens, fluid entering the heart backs up. This causes the veins in the body and tissues surrounding the heart to swell and become congested. Patients with diastolic failure are typically women, overweight, and elderly, and have high blood pressure and diabetes.

Failure on the Right Side (Right-Ventricular Heart Failure). Failure on the right side of the heart is most often a result of failure on the left. Because the right ventricle receives blood from the veins, failure here causes the blood to back up. As a result, the veins in the body and tissues surrounding the heart to swell. This causes swelling in the feet, ankles, legs, and abdomen. Pulmonary hypertension (increase in pressure in the lung's pulmonary artery) and lung disease may also cause right-sided heart failure.

Ejection Fraction. To help determine the severity of left-sided heart failure, doctors use an ejection fraction (EF) calculation, also called a left-ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). This is the percentage of the blood pumped out from the left ventricle during each heartbeat. An ejection fraction of 50 - 75% is considered normal. Patients with left-ventricular heart failure are classified as either having a preserved ejection fraction (greater than 50%) or a reduced ejection fraction (less than 50%).

Patients with preserved LVEF heart failure are more likely to be female and older, and have a history of high blood pressure and atrial fibrillation (a disturbance in heart rhythm).

Causes

Heart failure has many causes and can evolve in different ways.

- It can be a direct, latest-stage result of heart damage from one or more of several heart or circulation diseases.

- It can occur over time as the heart tries to compensate for abnormalities caused by these conditions, a condition called remodeling.

In all cases, the weaker pumping action of the heart means that less blood is sent to the kidneys. The kidneys respond by retaining salt and water. This in turn increases edema (fluid buildup) in the body, which causes widespread damage.

High Blood Pressure

Uncontrolled high blood pressure (hypertension) is a major cause of heart failure even in the absence of a heart attack. In fact, about 75% of cases of heart failure start with hypertension. It generally develops as follows:

- The heart muscles thicken to make up for increased blood pressure.

- The force of the heart muscle contractions weaken over time, and the muscles have difficulty relaxing. This prevents the normal filling of the heart with blood.

Coronary Artery Disease and Heart Attack

Coronary artery disease is the end result of a process called atherosclerosis (commonly called "hardening of the arteries"). It is the most common cause of heart attack and involves the build-up of unhealthy cholesterol in the arteries, with inflammation and injury in the cells of the blood vessels. The arteries narrow and become brittle. Heart failure in such cases most often results from a pumping defect in the left side of the heart.

People often survive heart attacks, but many eventually develop heart failure from the damage the attack does to the heart muscles.

Valvular Heart Disease

The valves of the heart control the flow of blood leaving and entering the heart. Abnormalities can cause blood to back up or leak back into the heart.

In the past, rheumatic fever, which scars the heart valves and prevents them from functioning properly, was a major cause of death from heart failure. Fortunately, antibiotics and other advances have now made this disease a minor cause of heart failure in industrialized nations. Birth defects may also cause abnormal valvular development. Although more children born with heart defects are now living to adulthood, they still face a higher than average risk for heart failure as they age.

Cardiomyopathy

Cardiomyopathy is a disorder that damages the heart muscles and leads to heart failure. There are several different types. Injury to the heart muscles may cause the heart muscles to thin out (dilate) or become too thick (become hypertrophic). In either case, the heart doesn't pump correctly. Viral myocarditis is a rare viral infection that involves the heart muscle and can produce either temporary or permanent heart muscle damage.

Dilated Cardiomyopathy. Dilated cardiomyopathy involves an enlarged heart ventricle. The muscles thin out, reducing the pumping action, usually on the left side. Although this condition is associated with genetic factors, the direct cause is often not known. (This is called idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.) In other cases, viral infections, alcoholism, and high blood pressure may increase the risk for this condition.

Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the heart muscles become thick and contract with difficulty. Some research indicates that this occurs because of a genetic defect that causes a loss of power in heart muscle cells and, subsequently, lower pumping strength. To compensate for this power loss, the heart muscle cells grow. This condition, rare in the general population, is often the cause of sudden death in young athletes.

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy. Restrictive cardiomyopathy refers to a group of disorders in which the heart chambers are unable to properly fill with blood because of stiffness in the heart. The heart is of normal size or only slightly enlarged. However, it cannot relax normally during the time between heartbeats when the blood returns from the body to the heart (diastole). The most common causes of restrictive cardiomyopathy are amyloidosis and scarring of the heart from an unknown cause (idiopathic myocardial fibrosis). It frequently occurs after a heart transplant.

Severe Lung Diseases

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (severe emphysema) and other major lung diseases are risk factors for right-side heart failure.

Pulmonary hypertension is increased pressure in the pulmonary arteries that carry blood from the heart to the lungs. The increased pressure makes the heart work harder to pump blood, which can cause heart failure. The development of right-sided heart failure in patients with pulmonary hypertension is a strong predictor of death within 6 - 12 months.

Thyroid Disorders

An overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) or underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) can have severe effects on the heart and increase the risk for heart failure.

Risk Factors

Nearly 6 million Americans are living with heart failure. About 670,000 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed each year. Although there has been a dramatic increase over the last several decades in the number of people who suffer from heart failure, survival rates have greatly improved.

Coronary artery disease, heart attack, and high blood pressure are the main causes and risk factors of heart failure. Other diseases that damage or weaken the heart muscle or heart valves can also cause heart failure. Heart failure is most common in people over age 65, African-Americans, and women.

Age

Heart failure risk increases with advancing age. Heart failure is the most common reason for hospitalization in people age 65 years and older.

Gender

Men are at higher risk for heart failure than women. However, women are more likely than men to develop diastolic heart failure (a failure of the heart muscle to relax normally), which is often a precursor to systolic heart failure (impaired ability to pump blood).

Ethnicity

African-Americans are more likely than Caucasians to develop heart failure before age 50 and die from the condition.

Family History and Genetics

People with a family history of cardiomyopathies (diseases that damage the heart muscle) are at increased risk of developing heart failure. Researchers are investigating specific genetic variants that increase heart failure risk.

Diabetes

People with diabetes are at high risk for heart failure, particularly if they also have coronary artery disease and high blood pressure. Some types of diabetes medications, such as rosiglitazone (Avandia) and pioglitazone (Actos), have been associated with heart failure. Chronic kidney disease caused by diabetes also increases heart failure risk.

Obesity

Obesity is associated with both high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes, conditions that place people at risk for heart failure. Evidence strongly suggests that obesity itself is a major risk factor for heart failure, particularly in women.

Lifestyle Factors

Smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and alcohol and drug abuse can increase the risk for developing heart failure.

Medications Associated with Heart Failure

Long-term use of high-dose anabolic steroids (male hormones used to build muscle mass) increases the risk for heart failure. The drug itraconazole (Sporanox), used to treat skin, nail, or other fungal infections, has occasionally been linked to heart failure. The cancer drug imatinib (Gleevec) has been associated with heart failure. Other chemotherapy drugs, such as doxorubicin, can increase the risk for developing heart failure years after cancer treatment. (Cancer radiation therapy to the chest can also damage the heart muscle.)

Complications

Nearly 290,000 people die from heart failure each year. Nevertheless, although heart failure produces very high mortality rates, treatment advances are improving survival rates.

Cardiac Cachexia. If patients with heart failure are overweight to begin with, their condition tends to be more severe. Once heart failure develops, however, an important indicator of a worsening condition is the occurrence of cardiac cachexia, which is unintentional rapid weight loss (a loss of at least 7.5% of normal weight within 6 months).

Impaired Kidney Function. Heart failure weakens the heart’s ability to pump blood. This can affect other parts of the body including the kidneys (which in turn can lead to fluid build-up). Decreased kidney function is common in patients with heart failure, both as a complication of heart failure and other diseases associated with heart failure (such as diabetes). Studies suggest that, in patients with heart failure, impaired kidney function increases the risks for heart complications, including hospitalization and death.

Congestion (Fluid Buildup). In left-sided heart failure, fluid builds up first in the lungs, a condition called pulmonary edema. Later, as right-sided heart failure develops, fluid builds up in the legs, feet, and abdomen. Fluid buildup is treated with lifestyle measures, such as reducing salt in the diet, as well as drugs, such as diuretics.

Arrhythmias (Irregular Beatings of the Heart)

- Atrial fibrillation is a rapid quivering beat in the upper chambers of the heart. It is a major cause of stroke and very dangerous in people with heart failure.

- Left bundle-branch block is an abnormality in electrical conduction in the heart. It develops in about 30% of patients with heart failure.

- Ventricular tachycardia and ventricular fibrillation are life-threatening arrhythmias that can occur in patients when heart function is significantly impaired.

Angina and Heart Attacks. While coronary artery disease is a major cause of heart failure, patients with heart failure are at continued risk for angina and heart attacks. Special care should be taken with sudden and strenuous exertion, particularly snow shoveling, during colder months.

Symptoms

Many symptoms of heart failure result from the congestion that develops as fluid backs up into the lungs and leaks into the tissues. Other symptoms result from inadequate delivery of oxygen-rich blood to the body's tissues. Since heart failure can progress rapidly, it is essential to consult a doctor immediately if any of the following symptoms are detected:

Fatigue. Patients may feel unusually tired.

Shortness of Breath (Dyspnea).

- Patients typically report that they feel out of breath after exertion. While this may begin only when climbing stairs or taking longer walks, it can eventually be present even when walking around the home. (Those who have chest pain or feel like a heavy weight is pressing on the chest should also be evaluated for possible angina.)

- Orthopnea refers to the shortness of breath patients may have when they lie flat at night. Patients may report that they need to use one or two pillows underneath their head and shoulders in order to be able to sleep. Sitting up with legs hanging over the side of the bed often relieves symptoms.

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea (PND) refers to sudden episodes that awaken a patient at night. Symptoms include severe shortness of breath and coughing or wheezing, which generally occur 1 - 3 hours after going to sleep. Unlike orthopnea, symptoms are not relieved by sitting up.

Fluid Retention (Edema) and Weight Gain. Patients may complain of foot, ankle, leg or abdominal swelling. In rare cases, swelling can occur in the veins of the neck. Fluid retention can cause sudden weight gain and frequent urination.

Wheezing or Cough. Patients may have asthma-like wheezing, or a dry hacking cough that occurs a few hours after lying down but then stops after sitting up.

Loss of Muscle Mass. Over time, patients may lose muscle weight due to low cardiac output and a significant reduction in physical activity.

Gastrointestinal Symptoms. Patients experience loss of appetite or a sense of feeling full after eating small amounts. They may also have abdominal pain.

Pulmonary Edema. When fluid in the lungs builds up, it is called pulmonary edema. When this happens, symptoms become more severe. These episodes may happen suddenly, or gradually build up over a matter of days:

- In addition to shortness of breath, patients sometimes have a cough that produces a pinkish froth.

- Patients may experience a bubbling sensation in the lungs and feel as if they are drowning.

- Typically, the skin is clammy and pale, sometimes nearly blue. This is a life-threatening situation, and the patient must go immediately to an emergency room.

Abnormal Heart Rhythms. Patients may have episodes of abnormally fast or slow heart rate.

Central Sleep Apnea. This sleep disorder results when the brain fails to signal the muscles to breathe during sleep. It occurs in up to half of people with heart failure. Sleep apnea causes disordered breathing at night. If heart failure progresses, the apnea may be so acute that a person, unable to breathe, may awaken from sleep in panic.

Diagnosis

Doctors can often make a preliminary diagnosis of heart failure by medical history and careful physical examination.

A thorough medical history may identify risks for heart failure that include:

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Abnormal cholesterol levels

- Heart disease or history of heart attack

- Thyroid problems

- Obesity

- Lifestyle factors (such as smoking, alcohol use, and drug use)

The following physical signs, along with medical history, strongly suggest heart failure:

- Enlarged heart

- Abnormal heart sounds

- Abnormal sounds in the lungs

- Swelling or tenderness of the liver

- Fluid retention in legs and abdomen

- Elevation of pressure in the veins of the neck

Laboratory Tests

Both blood and urine tests are used to check for problems with the liver and kidneys and to detect signs of diabetes. Lab tests can measure:

- Complete blood counts to check for anemia

- Kidney function blood and urine tests

- Sodium, potassium, and other electrolytes

- Cholesterol and lipid levels

- Blood sugar (glucose)

- Thyroid function

- Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), a hormone that increases during heart failure. BNP testing can be very helpful in correctly diagnosing heart failure in patients who come to the emergency room complaining of shortness of breath (dyspnea).

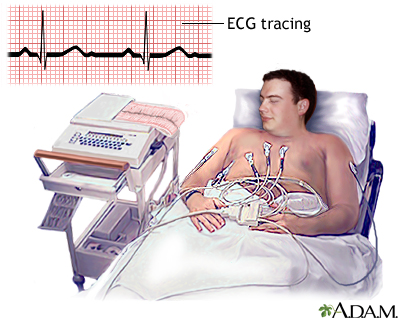

Electrocardiogram

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is a test that measures and records the electrical activity of the heart. It is also called an EKG. An electrocardiogram cannot diagnose heart failure, but it may indicate underlying heart problems. The test is simple and painless to perform. It may be used to diagnose:

- Previous heart attack

- Abnormal cardiac rhythms

- Enlargement of the heart muscle, which may help to determine long-term outlook

- A finding called a prolonged QT interval may indicate people with heart failure who are at risk for severe complications and therefore need more aggressive therapies.

A completely normal ECG means that heart failure is unlikely.

Echocardiography

The best diagnostic test for heart failure is echocardiography. Echocardiography is a noninvasive test that uses ultrasound to image the heart as it is beating. Cardiac ultrasounds provide the following information:

- Evaluations of valve function

- Information about how well the heart is pumping, especially a measurement called left ventricle ejection fraction (LVEF)

- Type of heart failure

- Changes in the structure of the heart that may be a result of heart failure

Doctors use information from the echocardiogram for calculating the ejection fraction (how much blood is pumped out during each heartbeat), which is important for determining the severity of heart failure. Stress echocardiography may be needed if coronary artery disease is suspected.

Angiography

Doctors may recommend angiography if they suspect that blockage of the coronary arteries is contributing to heart failure. This procedure is invasive.

- A thin tube called a catheter is inserted into one of the large arteries in the arm or leg.

- It is gently guided through the artery until it reaches the heart.

- The catheter measures internal blood pressure at various locations, giving the doctor a comprehensive picture of the extent and nature of the heart failure.

- Dye is then injected through the tube into the heart.

- X-rays called angiograms are taken as the dye moves through the heart and arteries.

- These images help locate problems in the heart's pumping action or blockage in the arteries.

Radionuclide Ventriculography. Radionuclide ventriculography is an imaging technique that uses a tiny amount of radioactive material (called a trace element). It is very sensitive in revealing heart enlargement or evidence of fluid accumulation around the heart and lungs. It may be done at the same time as coronary artery angiography. It can help diagnose or exclude the presence of coronary artery disease and helps demonstrate how the heart works during exercise.

Other Imaging Tests

Chest x-rays can show whether the heart is enlarged. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may also be used to evaluate the heart valves and arteries.

Exercise Stress Test

The exercise stress test measures heart rate, blood pressure, electrocardiographic changes, and oxygen consumption while a patient is performing physically, usually walking on a treadmill. It can help determine heart failure symptoms. Doctors also use exercise tests to evaluate long-term outlook and the effects of particular treatments. A stress test may be done using echocardiography or may be done as a nuclear stress test (myocardial perfusion imaging).

Treatment

Heart failure is classified into four stages (Stage A through Stage D) that reflect the development and progression of the condition. Treatment depends on the stage of heart failure.

Stage A is not technically heart failure, but indicates that a patient is at high risk for developing it. In Stage B, the patient has had damage to the heart (for example, from a heart attack) but does not yet have symptoms of heart failure. In Stage C, heart failure symptoms manifest.

Stage D is advanced heart failure accompanied by symptoms that may be difficult to manage with standard drug treatments and may require more technologically complex care (defibrillators, mechanical pumps, heart transplantation). The American Heart Association emphasizes the importance of a patient-centered approach to treatment decisions. Patients with advanced heart failure should have ongoing honest discussions with their health care providers concerning their personal preferences and quality of life goals.

Management of Risk Factors and Causes

Stage A. In Stage A, patients are at high risk for heart failure but do not show any symptoms or have structural damage of the heart. The first step in managing or preventing heart failure is to treat the primary conditions that cause or complicate heart failure. Risk factors include high blood pressure, heart diseases, diabetes, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and previous use of medications that damage the heart (such as some chemotherapy).

Important risk factors to manage include:

- Coronary artery disease. Treatment includes a healthy diet, exercise, smoking cessation, medications, and, possibly, bypass or angioplasty.

- Cholesterol and lipid problems. Treatments include lifestyle management and medications, especially statin drugs.

- High blood pressure. A normal systolic blood pressure is considered below 120 mm Hg, and a normal diastolic blood pressure is below 80 mm Hg. Patients with diabetes, atherosclerosis, or chronic kidney disease should maintain blood pressure readings of 130/80 or less, while other patients with high blood pressure should aim for readings no higher than 140/90. Effective reduction of blood pressure reduces the risk of heart failure by 30 - 50%.

- Diabetes. Treating type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes is extremely important for reducing the risk for heart disease. ACE inhibitors are especially beneficial, particularly for people with diabetes. Research suggests that metformin, a drug used to treat diabetes, may also help prevent heart failure.

- Obesity.

- Valvular abnormalities, such as aortic stenosis and mitral regurgitation. Surgery may be required.

- Abnormal health rhythms (arrhythmias). Ventricular assisted devices, notably biventricular pacers (BVPs), can help prevent hospitalizations for patients with these conditions.

- Anemia. Patients with heart failure and underlying anemia should have their anemia corrected. On occasion, this may require erythropoiesis-stimulating drugs.

- Thyroid function. Various medications are used to treat overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism) or underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism).

- Drugs. Avoid drugs that can worsen heart failure symptoms. Talk with your doctor about your heart failure before taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), calcium channel blockers (verapamil and diltiazem), thiazolidinediones (drugs used for diabetes), antitumor necrosis factor medications, and most drugs used to treat irregular heart rhythms (arrhythmia).

- Diet and Exercise. It is particularly important to reduce sodium (salt) intake to less than 1,500 mg a day. Patients should engage in medically supervised exercise programs. Dietary changes and exercise are important for treating all stages of heart failure.

Treatment Based on Heart Failure Stage

Stage B. Patients have a structural heart abnormality seen on echocardiogram or other imaging tests but no symptoms of heart failure. Abnormalities include left ventricular hypertrophy and low ejection fraction, asymptomatic valvular heart disease, and a previous heart attack. In addition to the treatment guidelines for Stage A, the following types of drugs and devices may be recommended for some patients:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) for patients who cannot tolerate ACE inhibitors.

- Beta blockers for patients with a recent or past history of heart attack. Also for patients who have not had a heart attack but who do have reduced LVEF identified in diagnostic tests.

Stage C. Patients have a structural abnormality and current or previous symptoms of heart failure, including shortness of breath, fatigue, and difficulty exercising. Treatment includes those for Stage A and B plus:

- Restrict dietary sodium (salt). Lowering sodium in the diet can help diuretics work better.

- ACE inhibitors or angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs).

- Beta blockers (bisoprolol, carvedilol, and sustained release metoprolol).

- Diuretics are recommended for most patients, with loop diuretics such as furosemide generally being the first-line choice.

- Aldosterone inhibitors are recommended for many patients. Digitalis may be prescribed for some patients.

- A hydralazine and nitrate combination (BiDil) should be used for African-American patients who are taking an ACE inhibitor, beta blocker, and diuretic and who still have heart failure symptoms.

- Exercise training for appropriate patients.

- Implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs) may be considered for patients with very low ejection fraction or those who have had dangerous arrhythmias.

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (pacemaker), with or without ICD, for some patients.

Stage D. Patients have end-stage symptoms that do not respond to standard treatments. Treatment focuses not only on survival but on symptom relief and quality of life issues. Treatment includes appropriate measures used for Stages A, B, and C plus:

- Strict control of fluid retention.

- Heart transplantation referral for appropriate patients.

- Left-ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as permanent therapy for patients who are not candidates for heart transplants. LVADs are surgically implanted to help pump blood through the body.

- Hospice and end-of-life care information for patients and families.

- Patients have the right to choose or decline treatments based on their personal preferences, values, and goals. Quality of life is as important a consideration as survival.

Managing Triggers of Heart Failure Symptoms

Whenever heart failure worsens, whether quickly or chronically over time, various factors must be considered as the cause:

- Dietary indiscretion. Sometimes as little as eating a sausage or some sauerkraut with a high sodium content is enough to precipitate an acute episode. Failure to comply with fluid and salt restrictions must be considered whenever heart failure worsens.

- Alcohol. Depending on the severity of a patient's heart failure, one or more drinks may suddenly worsen symptoms.

- Medication compliance. Patients may forget or purposely skip a medication, or they may not be able to afford or have access to medications.

- Angina or heart attack. Worsening of coronary artery disease may make the heart muscle less able to pump enough blood.

- Arrhythmias. Increases in the heart rate, or a slowing of the heart rate below normal, may also affect the ability of the heart to function. Likewise, an irregular heart rhythm such as atrial fibrillation may cause a flareup.

- Anemia. It is unclear whether anemia causes heart failure or is a symptom of heart failure. Some anemias may be treated with iron replacement therapy. A more significant anemia can cause a worsening of heart failure and should be treated promptly.

Medications

Many different medications are used in the treatment of heart failure. They include:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors

- Angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Beta blockers

- Diuretics

- Aldosterone blockers

- Digitalis

- Hydralazine and nitrates

- Statins

- Aspirin and warfarin

ACE Inhibitors

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are among the most important drugs for treating patients with heart failure. ACE inhibitors open blood vessels and decrease the workload of the heart. They are used to treat high blood pressure but can also help improve heart and lung muscle function. ACE inhibitors are particularly important for patients with diabetes, because they also help slow progression of kidney disease.

Brands and Indications. ACE inhibitors are used to treat Stage A high-risk conditions such as high blood pressure, heart disease, and diabetic nerve disorders (neuropathy). They are also used to treat Stage B patients who have had a heart attack or who have left ventricular systolic disorder, and Stage C patients with heart failure. Specific brands of ACE inhibitors include:

- Benazepril (Lotensin, generic)

- Captopril (Capoten, generic)

- Enalapril (Vasotec, generic)

- Fosinopril (Monopril, generic)

- Lisinopril (Prinivil, Zestril, generic)

- Moexipril (Univasc, generic)

- Perindopril (Aceon, generic)

- Quinapril (Accupril, generic)

- Ramipril (Altace, generic)

- Trandolapril (Mavik, generic)

Side Effects of ACE Inhibitors:

- Low blood pressure is the main side effect of ACE inhibitors. This can be severe in some patients, especially at the start of therapy.

- Irritating cough is a common side effect, which some people find intolerable. All ACE inhibitors can have this side effect, but angiotensin-receptor blockers do not.

- Although ACE inhibitors can protect against kidney disease, they also increase potassium retention by the kidneys. This increases the risk for cardiac arrest (when the heart stops beating) if potassium levels become too high. Because of this action, they are not generally given with potassium-sparing diuretics or potassium supplements.

- Patients who have difficulty tolerating ACE inhibitor side effects are usually switched to an angiotensin-receptor blocker (ARB).

Angiotensin-Receptor Blockers (ARBs)

ARBs, also known as angiotensin II receptor antagonists, are similar to ACE inhibitors in their ability to open blood vessels and lower blood pressure. They may have fewer or less-severe side effects than ACE inhibitors, especially coughing, and are sometimes prescribed as an alternative to ACE inhibitors. Some patients with heart failure take an ACE inhibitor along with an ARB.

Brands and Indications. ARBs are used to treat Stage A high-risk conditions such as high blood pressure and diabetic nerve disorders (neuropathy). They are also used to treat Stage B patients who have had a heart attack or who have left ventricular systolic disorder, and Stage C patients with heart failure. Specific brands include:

- Candesartan (Atacand)

- Valsartan (Diovan)

- Losartan (Cozaar)

- Eprosartan (Teveten)

- Irbesartan (Avapro)

- Olmesartan (Benicar)

- Telmisartan (Micardis)

- Azilsartan (Edarbi)

Common Side Effects

- Low blood pressure

- Dizziness and lightheadedness

- Raised potassium levels

- Drowsiness

Beta Blockers

Beta blockers are almost always used in combination with other drugs, such as ACE inhibitors and diuretics. They help slow heart rate and lower blood pressure. When used properly, beta blockers can reduce the risk of death or rehospitalization.

Brands and Indications. Beta blockers treat Stage A high blood pressure. They also treat Stage B patients (both those who have had a heart attack and those who have not had a heart attack but who have heart damage). A specialist should monitor patients with heart failure who take beta blockers. The three beta blockers that are best for treating Stage C patients with heart failure are:

- Carvedilol (Coreg, generic)

- Bisoprolol (Zebeta)

- Metoprolol succinate (Toprol XL, generic)

Beta Blocker Concerns

- Do not abruptly stop taking these drugs. The sudden withdrawal of beta blockers can increase the risk of angina and even a heart attack. If you need to stop your beta-blocker, your doctor may want you to slowly decrease the dose before stopping completely.

- Beta blockers are categorized as non-selective or selective. Non-selective beta blockers, such as carvedilol, can narrow bronchial airways. Patients with asthma, emphysema, or chronic bronchitis should not use non-selective beta blockers.

- Beta blockers can lower HDL (“good”) cholesterol, although the benefits they provide for coronary artery disease and heart failure outweigh any bad effects on cholesterol.

- These drugs can hide warning signs of low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) in patients with diabetes, especially those who take insulin.

Common Side Effects

- Fatigue and lethargy

- Vivid dreams and nightmares

- Depression

- Memory loss

- Dizziness and lightheadedness

- Reduced ability to exercise

- Coldness in extremities (legs, toes, arms, hands)

Check with your doctor about any side effects. Do not stop taking these drugs on your own.

Diuretics

Diuretics cause the kidneys to rid the body of excess salt and water. Fluid retention is a major symptom of heart failure. Aggressive use of diuretics can help eliminate excess body fluids, while reducing hospitalizations and improving exercise capacity. These drugs are also important to help prevent heart failure in patients with high blood pressure. In addition, certain diuretics, notably spironolactone (Aldactone, generic), block aldosterone, a hormone involved in heart failure. This drug class is beneficial for patients with more severe heart failure (Stages C and D).

Patients taking diuretics usually take a daily dose. Under the directions and care of a doctor or nurse, some patients may be taught to adjust the amount and timing of the diuretic when they notice swelling or weight gain.

Diuretics come in many brands and are generally inexpensive. Some need to be taken once a day, some twice a day. Treatment is usually started at a low dose and gradually increased. Diuretics are virtually always used in combination with other drugs, especially ACE inhibitors and beta blockers. There are three main types of diuretics:

Potassium-sparing diuretics.

- These include amiloride (Midamor, generic) and triamterene (Dyrenium, generic).

- Potassium-sparing diuretics have their own risks, which include dangerously high levels of potassium in people with existing elevated levels of potassium or in those with damaged kidneys. However, all diuretics are generally more beneficial than harmful.

- Patients should not take potassium supplements at the same time as this type of diuretic without their doctor's knowledge, and may need to avoid foods with high potassium content.

Thiazide diuretics. These include chlorothiazide (Diuril, generic), chlorthalidone (Clorpres, generic), indapamide (Lozol, generic), hydrochlorothiazide (Esidrix, generic), and metolazone (Zaroxolyn, generic).

Loop diuretics. These are considered the preferred diuretic type for most patients with heart failure.

- Loop diuretics include bumentanide (Bumex, generic), furosemide (Lasix, generic), and torsemide (Demadex, generic).

- Loop and thiazide diuretics deplete the body's supply of potassium, which, if left untreated, increases the risk for arrhythmias. (Arrhythmias are heart rhythm disturbances that can, in rare instances, lead to cardiac arrest). In such cases, doctors will prescribe lower doses of the current diuretic, recommend potassium supplements, or use potassium-sparing diuretics either alone or in combination with a thiazide.

- Dehydration (loss of too much fluid) is also another concern.

Common Side Effects

- Fatigue

- Depression and irritability

- Reduced sexual function

Aldosterone Blockers

Aldosterone is a hormone that is critical in controlling the body's balance of salt and water. Excessive levels may play important roles in hypertension and heart failure. Drugs that block aldosterone are prescribed for some patients with symptomatic heart failure. They have been found to reduce death rates for patients with heart failure and coronary artery disease, especially after a heart attack. These blockers pose some risk for high potassium levels. Brands include:

- Spironolactone (Aldactone, generic)

- Eplerenone (Inspra, generic)

Elevated levels of potassium in the blood are also a concern with these drugs. Patients should not take potassium supplements at the same time as this drug without their doctor's knowledge and may need to avoid foods with high potassium content.

Digitalis

Digitalis is derived from the foxglove plant. It has been used to treat heart disease since the 1700s. Digoxin (Lanoxin, generic) is the most commonly prescribed digitalis preparation. Digoxin decreases heart size and reduces certain heart rhythm disturbances (arrhythmias).

Unfortunately, digitalis does not reduce mortality rates, although it does reduce hospitalizations and worsening of heart failure. Controversy has been ongoing for more than 100 years over whether the benefits of digitalis outweigh its risks and adverse effects.

Digitalis may be useful for select patients with left-ventricular systolic dysfunction who do not respond to other drugs (diuretics, ACE inhibitors). It may also be used for patients who have atrial fibrillation.

Side Effects and Problems. While digitalis is generally a safe drug, it can have toxic side effects due to overdose or other accompanying conditions. The most serious side effects are arrhythmias (abnormal heart rhythms that can be life threatening). Early signs of toxicity may be irregular heartbeat, nausea and vomiting, stomach pain, fatigue, visual disturbances (such as yellow vision, seeing halos around lights, flickering or flashing of lights), and emotional and mental disturbances.

Many factors increase the chance for side effects.

- Advanced age

- Low blood potassium levels (which may be caused by diuretics)

- Hypothyroidism

- Anemia

- Valvular heart disease

- Impaired kidney function

Digitalis also interacts with many other drugs, including quinidine, amiodarone, verapamil, flecainide, amiloride, and propafenone.

For most patients with mild-to-moderate heart failure, low-dose digoxin may be as effective as higher doses. If side effects are mild, patients should still consider continuing with digitalis if they experience other benefits.

Hydralazine and Nitrates

Hydralazine and nitrates are two older drugs that help relax arteries and veins, thereby reducing the heart's workload and allowing more blood to reach the tissues. They are used primarily for patients who are unable to tolerate ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers. In 2005, the FDA approved BiDil, a drug that combines isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine. BiDil is approved to specifically treat heart failure in African-American patients.

Statins

Statins are important drugs used to lower cholesterol and to prevent heart disease leading to heart failure. These drugs include lovastatin (Mevacor, generic), pravastatin (Pravachol, generic), simvastatin (Zocor, generic), fluvastatin (Lescol), atorvastatin (Lipitor, generic), rosuvastatin (Crestor), and pitavastatin (Livalo). Atorvastatin is specifically approved to reduce the risks for hospitalization for heart failure in patients with heart disease.

Anti-Platelet and Anticoagulant Drugs

Aspirin. Aspirin is a type of non-steroid anti-inflammatory (NSAID). Aspirin is recommended for protecting patients with heart disease, and can safely be used with ACE inhibitors, particularly when it is taken in lower dosages (75 - 81 mg).

Warfarin (Coumadin, generic). Warfarin is recommended only for patients with heart failure who also have:

- Atrial fibrillation

- A history of blood clots to the lungs, stroke, or transient ischemic attack

- A blood clot in one of their heart chambers

Other Drugs

Nesiritide (Natrecor). Nesiritide is an intravenous drug that has been used for hospitalized patients with decompensated heart failure. Decompensated heart failure is a life-threatening condition in which heart failure progresses over the course of minutes or a few days, often as the result of a heart attack or sudden and severe heart valve problems. Because nesiritide may cause serious kidney damage and has been linked to an increased risk of death from heart failure, the drug is of limited value.

Erythropoietin. Many patients with chronic heart failure are also anemic. Treatment of these patients with erythropoietin has been shown to provide some benefit for heart failure control and hospitalization risk. However, erythropoietin therapy can also increase the risk of blood clots. The exact role of this drug for the treatment of anemia in patients with heart failure is not yet decided.

Tolvaptan. Tolvaptan (Samsca) is a drug approved for treating hyponatremia (low sodium levels) associated with heart failure and other conditions.

Levosimendan. Levosimendan is an experimental drug that is being investigated as a treatment for severely ill patients with heart failure. It belongs to a new class of drugs called calcium sensitizers that may help improve heart contractions and blood flow. The drug appears to reduce levels of BNP (brain natriuretic peptide), a chemical marker for heart failure severity.

Surgery and Devices

Revascularization Surgery

Revascularization surgery helps to restore blood flow to heart affected by coronary artery disease. It can treat blocked arteries in patients with coronary artery disease and may help select patients with heart failure. Surgery types include coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and angioplasty (also called percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]). CABG is a traditional type of open heart surgery. Angioplasty uses a catheter to inflate a balloon inside the artery. A metal stent may also be inserted during an angioplasty procedure.

Pacemakers

Pacemakers, also called pacers, help regulate the heart’s beating action, especially when the heart beats too slowly. Biventricular pacers (BVPs) are a special type of pacemaker used for patients with heart failure. Because BVPs help the heart’s left and right chambers beat together, this treatment is called cardiac resynchronization therapy (CST).

BVPs are recommended for patients with moderate-to-severe heart failure that is not controlled with medication therapy and who have evidence of left-bundle branch block on their EKG. Left-bundle branch block is a condition in which the electrical impulses in the heart do not follow their normal pattern, causing the heart to pump inefficiently.

Implantable Cardioverter Defibrillators (ICDs)

Patients with enlarged hearts are at risk for having serious cardiac arrhythmias (abnormal heartbeats) that are associated with sudden death. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) can quickly detect life-threatening arrhythmias. The ICD is designed to convert any abnormal heart rhythm back to normal by sending an electrical shock to your heart. This action is called defibrillation. This device can also work as a pacemaker.

In recent years, certain ICD models and biventricular pacemaker-defibrillators have been recalled by the manufacturers because of circuitry flaws. However, doctors stress that the chance of an ICD or pacemaker saving a person’s life far outweigh the possible risks of these devices failing.

Ventricular Assist Devices

Ventricular assist devices are mechanical devices that help improve pumping actions. They are used as a bridge to transplant for patients who are on medications but still have severe symptoms and are awaiting a donor heart. In some cases, they may delay the need for a transplant. Therefore they may be used as short-term (less than 1 week) or longer term support.

Ventricular assist devices include:

- Left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) are used for patients whose heart beat has slowed dangerously to help take over the pumping action of the failing heart. Until recently, these machines required remaining in the hospital. Smaller battery-powered implanted LVAD units are now allowing many patients to leave the hospital while they wait for a transplant.

- Intra-aortic balloon pumps are helpful for temporarily maintaining heart function in patients with left-side failure who are waiting for transplants and for those who develop a sudden and severe deterioration of heart function. The IABP is an implanted thin balloon that is usually inserted into the artery in the leg and threaded up to the aorta leading from the heart. Its pumping action is generating by inflating and deflating the balloon at certain rates.

- Fully implanted miniature artificial pumps that assist the heart are also being tested.

The risks and complications involved with many of these devices include bleeding, blood clots, and right-side heart failure. Infections are a particular hazard.

Heart Transplantation

Patients who suffer from severe heart failure and whose symptoms do not improve with drug therapy or mechanical assistance may be candidates for heart transplantation. About 2,000 heart transplant operations are performed in the United States each year, but thousands more patients wait on a list for a donor heart.

The most important factor for heart transplant eligibility is overall health. Chronological age is less important. Most heart transplant candidates are between the ages of 50 - 64 years.

While the risks of this procedure are high, the 1-year survival rate is about 88% for men and 77% for women. Five years after a heart transplant, about 73% of men and 67% of women remain alive. In general, the highest risk factors for death three or more years after a transplant operation are coronary artery disease and the adverse effects (infection and certain cancers) of immunosuppressive drugs used in the procedure. The rejection rates in older people appear to be similar to those of younger patients.

Implantable Artificial Heart

Abiocor is a permanent implantable artificial heart. It is available only for patients who are not eligible for a heart transplant and who are not expected to live more than a month without medical treatment. The device requires a large chest cavity, which means that most women are not eligible for it.

Lifestyle Changes

Up to half of patients hospitalized for heart failure are back in the hospital within 6 months. Many people return because of lifestyle factors, such as poor diet, failure to comply with medications, and social isolation.

Rehabilitation

Programs that offer intensive follow-up to ensure that the patient complies with lifestyle changes and medication regimens at home can reduce rehospitalization and improve survival. Patients without available rehabilitation programs should seek support from local and national heart associations and groups. A strong emotional support network is also important.

Monitoring Weight Changes

Patients should weigh themselves each morning and keep a record. Any changes are important:

- A sudden increase in weight of more than 2 - 3 pounds may indicate fluid accumulation and should prompt an immediate call to the doctor.

- Rapid wasting weight loss over a few months is a very serious sign and may indicate the need for surgical intervention.

Dietary Factors

Sodium (Salt) Restriction. All patients with heart failure should limit their sodium (salt) intake to less than 1,500 mg a day, and in severe cases, very stringent salt restriction may be necessary. Patients should not add salt to their cooking and their meals. They should also avoid foods high in sodium. These salty foods include ham, bacon, hot dogs, lunch meats, prepared snack foods, dry cereal, cheese, canned soups, soy sauce, and condiments. Some patients may need to reduce the amount of water they consume. People with high cholesterol levels or diabetes require additional dietary precautions.

Here are some tips to lower your salt and sodium intake:

- Look for foods that are labeled “low-sodium,” “sodium-free,” “no salt added,” or “unsalted.” Check the total sodium content on food labels. Be especially careful of canned, packaged, and frozen foods. A nutritionist can teach you how to understand these labels.

- Don’t cook with salt or add salt to what you are eating. Try pepper, garlic, lemon, or other spices for flavor instead. Be careful of packaged spice blends as these often contain salt or salt products (like monosodium glutamate, MSG).

- Avoid processed meats (particularly cured meats, bacon, hot dogs, sausage, bologna, ham, and salami).

- Avoid foods that are naturally high in sodium, like anchovies, nuts, olives, pickles, sauerkraut, soy and Worcestershire sauces, tomato and other vegetable juices, and cheese.

- Take care when eating out. Stick to steamed, grilled, baked, boiled, and broiled foods with no added salt, sauce, or cheese.

- Use oil and vinegar, rather than bottled dressings, on salads.

- Eat fresh fruit or sorbet when having dessert.

Exercise

People with heart failure used to be discouraged from exercising. Now, doctors think that exercise, when performed under medical supervision, is extremely important for stable patients with stable conditions. Studies have reported that patients with stable conditions who engage in regular moderate exercise (three times a week) have a better quality of life and lower mortality rates than those who do not exercise. However:

- Exercise is not appropriate for all patients with heart failure. If you have heart failure, always consult your doctor before starting an exercise program.

- People who are approved for, but not used to, exercise should start with 5 - 15 minutes of easy exercise with frequent breaks. Although the goal is to build up to 30 - 45 minutes of walking, swimming, or low-impact aerobic exercises three to five times every week, even shorter times spent exercising are useful.

Studies report benefits from specific exercises:

- Progressive strength training may be particularly useful for patients with heart failure since it strengthens muscles, which commonly deteriorate in this disorder. Strength training typically uses light weights, weight machines, or even the body's weight (leg raises or sit-ups, for example). Even performing daily handgrip exercises can improve blood flow through the arteries.

- Patients who exercise regularly using supervised treadmill and stationary-bicycle exercises can increase their exercise capacity. Exercising the legs may help correct problems in heart muscles. Exercise has also been associated with reduced inflammation in blood vessels.

Bed Rest

Some people with severe heart failure may need bed rest. To reduce congestion in the lungs, the patient's upper body should be elevated. For most patients, resting in an armchair is better than lying in bed. Relaxing and contracting leg muscles is important to prevent clots. As the patient improves, a doctor will progressively recommend more activity.

Stress Reduction

Stress reduction techniques, such as meditation and relaxation response methods, may have direct physical benefits. Anxiety can cause the heart to work harder and beat faster.

Herbs and Supplements

Patients with heart failure may resort to alternative remedies. Such remedies are often ineffective and may have severe or toxic effects. Of particular note for patients with heart failure is an interaction between St. John's wort (an herbal medicine used for depression) and digoxin (a heart drug). St. John's wort can significantly interfere with this drug.

Fish Oil Supplements. Some research shows that a daily capsule of fish oil may help improve survival in patients with heart failure. Fish oil contains omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, a healthy kind of fat. However, while evidence is not conclusive, some studies have suggested that fish oil supplements may not be safe for patients with implanted cardiac defibrillators.

Coenzyme Q10 and Vitamin E. Small studies suggested that coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) may help patients with heart failure, particularly when combined with vitamin E. CoQ10 is a vitamin-like substance found in organ meats and soybean oil. More recent studies, however, have found that CoQ10 and vitamin E do not help the heart or prevent heart disease. In fact, vitamin E supplements may actually increase the risk of heart failure, especially for patients with diabetes or vascular diseases.

Other Vitamins and Supplements. A wide variety of other vitamins (thiamin, B6, and C), minerals (calcium, magnesium, zinc, manganese, copper, selenium), nutritional supplements (carnitine, creatine), and herbal remedies (hawthorn) have been proposed as treatments for heart failure. None have been adequately tested. There is no evidence that a particular vitamin or supplement can cure heart failure. In any case, vitamins are best consumed through the food sources contained in a healthy diet.

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been several reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Resources

- www.nhlbi.nih.gov -- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

- www.heart.org-- American Heart Association

- www.acc.org -- American College of Cardiology

- www.hfsa.org -- Heart Failure Society of America

- www.unos.org -- United Network for Organ Sharing

- www.organdonor.gov -- US government organ donor site

References

Adabag S, Roukoz H, Anand IS, Moss AJ. Cardiac resynchronization therapy in patients with minimal heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011 Aug 23;58(9):935-41.

Allen LA, Stevenson LW, Grady KL, Goldstein NE, Matlock DD, Arnold RM, et al. Decision Making in Advanced Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012 Apr 17;125(15):1928-1952. Epub 2012 Mar 5.

Al-Majed NS, McAlister FA, Bakal JA, Ezekowitz JA. Meta-analysis: cardiac resynchronization therapy for patients with less symptomatic heart failure. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Mar 15;154(6):401-12. Epub 2011 Feb 14.

Bibbins-Domingo K, Pletcher MJ, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Gardin JM, et al. Racial differences in incident heart failure among young adults. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 19;360(12):1179-90.

Carlson MD, Wilkoff BL, Maisel WH, Carlson MD, Ellenbogen KA, Saxon LA, et al. Recommendations from the Heart Rhythm Society Task Force on Device Performance Policies and Guidelines Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF) and the American Heart Association (AHA) and the International Coalition of Pacing and Electrophysiology Organizations (COPE). Heart Rhythm. 2006 Oct;3(10):1250-73.

Epstein AE, Dimarco JP, Ellenbogen KA, Estes NA 3rd, Freedman RA, Gettes LS, et al. ACC/AHA/HRS 2008 Guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities. Heart Rhythm. 2008 Jun;5(6):e1-62. Epub 2008 May 21.

Ghanbari H, Dalloul G, Hasan R, Daccarett M, Saba S, David S, et al. Effectiveness of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators for the primary prevention of sudden cardiac death in women with advanced heart failure: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Sep 14;169(16):1500-6.

Gissi-HF Investigators, Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP, Marchioli R, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, et al. Effect of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2008 Oct 4;372(9645):1223-30. Epub 2008 Aug 29.

Greenberg B and Kahn AM. Clinical assessment of heart failure. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Saunders; 2012:chap 26.

Haykowsky MJ, Liang Y, Pechter D, Jones LW, McAlister FA, Clark AM. A meta-analysis of the effect of exercise training on left ventricular remodeling in heart failure patients: the benefit depends on the type of training performed. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007 Jun 19;49(24):2329-36. Epub 2007 Jun 4.

Heart Failure Society of America, Lindenfeld J, Albert NM, Boehmer JP, Collins SP, Ezekowitz JA, et al. HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J Card Fail. 2010 Jun;16(6):e1-194.

Hildebrandt P. Systolic and nonsystolic heart failure: equally serious threats. JAMA. 2006 Nov 8;296(18):2259-60.

Jessup M, Abraham WT, Casey DE, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, et al. 2009 focused update: ACCF/AHA Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. Circulation. 2009 Apr 14;119(14):1977-2016. Epub 2009 Mar 26

Khush KK, Waters DD, Bittner V, Deedwania PC, Kastelein JJ, Lewis SJ, et al. Effect of high-dose atorvastatin on hospitalizations for heart failure: subgroup analysis of the Treating to New Targets (TNT) study. Circulation. 2007 Feb 6;115(5):576-83. Epub 2007 Jan 29.

Mann DL. Pathophysiology of heart failure. In: Bonow RO, Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, eds. Braunwald's Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. 9th ed. Saunders; 2012:chap 25.

Mant J, Al-Mohammad A, Swain S, Laramée P; Guideline Development Group. Management of chronic heart failure in adults: synopsis of the National Institute For Health and Clinical Excellence guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Aug 16;155(4):252-9.

McAlister FA, Ezekowitz J, Dryden DM, Hooton N, Vandermeer B, Friesen C, et al. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy and Implantable Cardiac Defibrillators in Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction. Evidence Report/Technology Assessment No. 152 (Prepared by the University of Alberta Evidence-based Practice Center under Contract No. 290-02-0023). AHRQ Publication No. 07-E009. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. June 2007.

Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, Klein H, Brown MW, Daubert JP, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 1;361(14):1329-38. Epub 2009 Sep 1. Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events.

O'Connor CM, Starling RC, Hernandez AF, Armstrong PW, Dickstein K, Hasselblad V, et al. Effect of nesiritide in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jul 7;365(1):32-43.

Schocken DD, Benjamin EJ, Fonarow GC, Krumholz HM, Levy D, Mensah GA, et al. Prevention of heart failure: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Councils on Epidemiology and Prevention, Clinical Cardiology, Cardiovascular Nursing, and High Blood Pressure Research; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group; and Functional Genomics and Translational Biology Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2008 May 13;117(19):2544-65. Epub 2008 Apr 7.

|

Review Date:

5/28/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |