Hepatitis

Highlights

Hepatitis C Screening for “Baby Boomers”

In 2012, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that everyone born from 1945 - 1965 (the “baby boom” generation) get a one-time test for hepatitis C. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is currently updating its recommendations for hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening. In a draft statement, the USPSTF recommended that doctors consider screening people born during these years.

The CDC’s reasons for its recommendations include:

- People born between 1945 - 1965 comprise 25% of the U.S. population but account for 75% of adults infected with HCV. They are 5 times more likely than other American adults to be infected with HCV.

- Most patients with hepatitis C do not experience symptoms and are unaware they are infected. Chronic hepatitis C can be present for decades and liver damage can occur before people experience symptoms.

- Compared to other Americans, people of the baby boom generation face an increased risk of dying from hepatitis C-related illnesses such as liver cancer and cirrhosis. A CDC study found that deaths from hepatitis C have been increasing steadily in recent years, especially among middle-aged people.

- Testing can help prevent deaths. Advances in treatment with new drug therapies are saving many lives.

Vaccines are available to prevent hepatitis A and B. There is no vaccine for hepatitis C.

New Drug Treatments for Hepatitis C

In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved two new drugs, telaprevir (Incivek) and boceprevir (Victrelis), for treatment of adult patients with genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C infection. Genotype 1 is the most common type of hepatitis C virus and is the most difficult to treat.

Patients take either telaprevir or boceprevir as daily pills in combination with peginterferon alfa and ribavirin, the standard hepatitis C drug regimen. In clinical trials, the three-drug combination successfully cured up to 75% of patients. In contrast, the two-drug combination of peginterferon alfa and ribavirin cures only about 45% of patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C.

The approval of these medications marks a breakthrough for hepatitis C treatment. However, these drugs are very expensive and can cause some serious side effects, in particular anemia and life-threatening skin rash. They can also cause birth defects. Both men and women who take these new drugs should use two forms of birth control during treatment.

Introduction

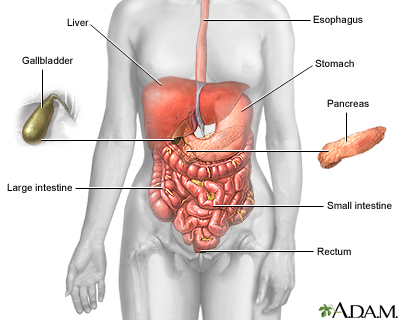

Hepatitis means "inflammation of the liver." It is a disorder in which viruses or other mechanisms produce inflammation in liver cells, resulting in their injury or destruction. The liver is the largest internal organ in the body, occupying the upper right area of the abdomen. It performs over 500 vital functions. Some key roles are:

- The liver processes all of the nutrients the body requires, including proteins, glucose, vitamins, and fats.

- The liver is the body’s “factory” where many important proteins are made. The blood protein albumin is one example that is often under-produced in patients with cirrhosis.

- The liver manufactures bile, the greenish fluid stored in the gallbladder that helps digest fats.

- One of the liver's major contributions is to render harmless potentially toxic substances, including alcohol, ammonia, nicotine, drugs, and harmful by-products of digestion.

Damage to the liver can impair these and many other processes. Hepatitis varies in severity from a self-limited condition with total recovery to a life-threatening or life-long disease. It can occur from many different causes:

- In the most common kind of hepatitis (viral hepatitis), specific viruses injure liver cells and the body activates its immune system to fight off the infection. Certain immune factors that cause inflammation and injury become overproduced.

- Hepatitis can also result from an autoimmune condition, in which abnormally targeted immune factors attack the body's own liver cells.

- Inflammation of the liver can also occur from medical problems, drugs, alcoholism, chemicals, and environmental toxins.

All hepatitis viruses can cause an acute (short term) form of liver disease. Some specific hepatitis viruses (B, C, and D), and some non-viral forms of hepatitis, can cause chronic (long term) liver disease. (Hepatitis A and E viruses do not cause chronic disease.) In some cases, acute hepatitis develops into a chronic condition, but chronic hepatitis can also develop without an acute phase. Although chronic hepatitis is generally the more serious condition, patients with either condition can have varying degrees of severity.

Acute Hepatitis. Acute hepatitis can begin suddenly or gradually, but it has a limited course and rarely lasts beyond 1 or 2 months, although it may last up to 6 months. Usually, there is only minimal liver cell damage and scant evidence of immune system activity. Rarely, acute hepatitis due to hepatitis B can cause severe, even life-threatening, liver damage.

Chronic Hepatitis. If hepatitis does not resolve after 6 months, it is considered chronic. The chronic forms of hepatitis last for prolonged periods. Doctors usually categorize chronic hepatitis by indications of severity:

- Chronic persistent hepatitis is usually mild and does not progress or progresses slowly, causing limited damage to the liver.

- Chronic active hepatitis involves progressive and often extensive liver damage and cell injury.

Viral Hepatitis

Most cases of hepatitis are caused by viruses that infect liver cells and begin multiplying. They are identified by the letters A through G:

- Hepatitis A, B, and C are the most common viral forms of hepatitis and are the primary focus of this report.

- Hepatitis D and E are less common hepatitis viruses. Hepatitis D is a serious form of hepatitis that can be chronic. It is associated with hepatitis B because the D virus relies on the B virus to replicate. (Therefore, hepatitis D cannot exist without the B virus also being present.) Hepatitis E, like hepatitis A, is an acute form of hepatitis that is transmitted by contact with contaminated food or water.

- Researchers are investigating additional viruses that may be implicated in hepatitis unexplained by the currently known viruses.

The name of each type of viral hepatitis condition corresponds to the virus that causes it. For example, hepatitis A is caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis B is caused by hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C is caused by hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Scientists do not know exactly how these viruses actually cause hepatitis. As the virus reproduces in the liver, several proteins and enzymes, including many that attach to the surface of the viral protein, are also produced. Some of these may be directly responsible for liver inflammation and damage.

Non-Viral Forms of Hepatitis

Autoimmune Hepatitis. Autoimmune hepatitis is a rare form of chronic hepatitis. Like other autoimmune disorders, its exact cause is unknown. Autoimmune hepatitis may develop on its own or it may be associated with other autoimmune disorders, such as systemic lupus erythematosus. In autoimmune disorders, a misdirected immune system attacks the body's own cells and organs (in this case the liver).

Alcoholic Hepatitis. About 20% of heavy drinkers develop alcoholic hepatitis, usually between the ages of 40 - 60 years. In the body, alcohol breaks down into various chemicals, some of which are very toxic to the liver. After years of drinking, liver damage can be very severe, leading to cirrhosis. Although heavy drinking itself is the major risk factor for alcoholic hepatitis, genetic factors may play a role in increasing a person's risk for alcoholic hepatitis. Women who abuse alcohol are at higher risk for alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis than are men who drink heavily. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #75: Cirrhosis.]

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) affects 10 - 24% of the population. It covers several conditions, including nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFLD has features similar to alcoholic hepatitis, particularly a fatty liver, but it occurs in individuals who drink little or no alcohol. Severe obesity and diabetes are the major risk factors for NAFLD and they also increase the likelihood of complications from NAFLD. NAFLD is usually benign and very slowly progressive. In certain patients, however, it can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure, or liver cancer. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #75: Cirrhosis.]

Drug-Induced Hepatitis. Because the liver plays such a major role in metabolizing drugs, hundreds of medications can cause reactions that are similar to those of acute viral hepatitis. Symptoms can appear anytime after starting drug treatment. In most cases, they disappear when the drug is withdrawn, but in rare circumstances they may progress to serious liver disease. Drugs most noted for liver interactions include halothane, isoniazid, methyldopa, phenytoin, valproic acid, and the sulfonamide drugs. Very high doses of acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) have been known to cause severe liver damage and even death, particularly when used with alcohol.

Toxin-Induced Hepatitis. Certain types of plant and chemical toxins can cause hepatitis. These include toxins found in poisonous mushrooms, and industrial chemicals such as vinyl chloride.

Metabolic-Disorder Associated Hepatitis. Hereditary metabolic disorders, such as hemochromatosis (accumulation of iron in the body) and Wilson’s disease (accumulation of copper in the body) can cause liver inflammation and damage.

Risk Factors and Transmission

Depending on the type of hepatitis virus, there are different ways that people can acquire hepatitis. In the United States, the main ways that people contract hepatitis are:

- Hepatitis A. Through contaminated food and water

- Hepatitis B. Through sexual contact or contaminated blood or body fluids

- Hepatitis C. Through contact with infected blood, usually by sharing drug injection needles and syringes and in rare cases through sexual contact

Hepatitis A

The hepatitis A virus is excreted in feces and transmitted by ingesting contaminated food or water. An infected person can transmit hepatitis to others if they do not take strict sanitary precautions, such as thoroughly washing hands before food preparation

People can become infected with hepatitis A by:

- Eating or drinking food or water contaminated with hepatitis A virus. Contaminated fruits, vegetables, shellfish, ice, and water are common sources of hepatitis A transmission.

- Engaging in unsafe sexual practices (oral-anal contact).

People at high risk for hepatitis A infection include:

- International travelers. Hepatitis A is the hepatitis strain people are most likely to encounter in the course of international travel to developing countries.

- Day care employees and children. Many cases of hepatitis A occur among day care employees and children who attend day care. Risks can be reduced if hygienic precautions are used, particularly when changing and handling diapers.

- People living in a household with someone who has hepatitis A

- Men who have sex with men

- Users of illegal drugs

Hepatitis B

The hepatitis B virus is transmitted through blood, semen, and vaginal secretions. Situations that can cause hepatitis B transmission include:

- Sexual contact with an infected person (using a condom can help reduce risk)

- Sharing needles and drug injection equipment

- Sharing personal items, (such as toothbrushes, razors, and nail clippers), with an infected person

- Having direct contact with blood of an infected person, through touching open wounds or needlesticks

- During delivery, an infected mother can transmit the hepatitis B virus to her baby.

The CDC recommends routine testing for chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection for the following high risk groups:

- People born in regions with high rates of hepatitis B infection. Hepatitis B is very common in Asian and Pacific Island countries. In the United States, 1 in 10 Asian Americans are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus. Other regions with high rates of HBV prevalence include Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, South and Central America, and the Caribbean. US-born people not vaccinated as infants whose parents were born in these regions should also be screened for HBV.

- People who use injected drugs or who share needles

- Men who have sex with men

- People receiving chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapy for certain medical conditions including cancer, organ transplantation, or rheumatologic or intestinal disorders

- Donors of blood, organs, or semen

- Hemodialysis patients

- All pregnant women and infants born to mothers infected with HBV; pregnant women should be screened for HBV at their first neonatal visit

- People who have sex with an infected person or who live in a household with an infected person

- Health care workers and others exposed to blood products and needlestick devices.

- People infected with HIV

Other people at high risk for hepatitis B virus infection include:

- People who have multiple sex partners

- International travelers to countries with high rates of hepatitis B

- People who received a blood transfusion or received a blood clotting product prior to 1987, when better procedures were implemented to screen donors and blood products for the hepatitis B virus.

Hepatitis C

The hepatitis C virus is transmitted by contact with infected human blood.

- Most people are infected through sharing needles or other drug injection equipment.

- Less commonly, hepatitis C is spread through sexual contact (only rarely), sharing household items such as razors or toothbrushes, or through birth to a mother infected with hepatitis C.

The CDC recommends hepatitis C virus (HCV) testing for:

- People born betwen 1945 - 1964. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends one-time testing for everyone who was born during these years. “Baby boomers” account for nearly 75% of all HCV infections in the United States. Most people with chronic HCV do not realize they are infected. Middle-aged people are at the greatest risk for developing and dying from liver cancer and other serious HCV-related illnesses. Advances in drug treatments are now helping cure or stop disease progression for many people with HCV. For these reasons, the CDC advocates HCV screening for people of this generation.

- Current and former drug injection users. Even if it has been many years since you injected drugs, you should get tested.

- People who received a blood transfusion, blood product, or organ before 1992 when procedures were implemented to screen blood for hepatitis C

- People who received a blood clotting product prior to 1987, when screening procedures were implemented

- People who have liver disease or who have had abnormal liver test results

- Hemodialysis patients

- Healthcare workers who may be exposed to needlesticks

- People infected with HIV

Other people at high risk for HCV infection include:

- People who have had tattooing or body piercing performed with non-sterile instruments

- Children born to mothers infected with hepatitis C

Prevention

Prevention of Hepatitis A

Vaccination. Hepatitis A is preventable by vaccination. Two vaccines (Havrix, Vaqta) are available, both very safe and effective. They are given in 2 shots, 6 months apart. A combination Hep A - Hep B vaccine (Twinrix) that contains both Havrix and Engerix-B (a hepatitis B vaccine) is also available for people age 18 years and older. It is given as 3 shots over a 6-month period.

The CDC recommend hepatitis A vaccination for:

- Children at age 1 year (12 - 23 months)

- Travelers to countries where hepatitis A is prevalent; they should receive the hepatitis A vaccine at least 2 weeks prior to departure.

- Men who have sex with other men

- Users of illegal drugs, especially those who inject drugs

- People with chronic liver diseases, such as hepatitis B or C

Others who may benefit include:

- People who have chronic liver disease

- People who receive clotting factor concentrate to treat hemophilia or other clotting disorders

- Military personnel

- Employees of child day-care centers

- People who care for institutionalized patients

Prevention after Exposure to Hepatitis A. Unvaccinated people who have recently been exposed to hepatitis A may be able to prevent hepatitis A by receiving injection with immune globulin (IG) or the hepatitis A vaccine. These shots must be given within 2 weeks after exposure to be effective. In the past, immune globulin was the standard postexposure prophylaxis (preventive treatment after exposure) for hepatitis A. However, recent studies have indicated that the hepatitis A vaccine provides as good protection as immune globulin. The CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices now recommends the vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis for healthy individuals between the ages of 1 - 40 years. Others should be given immune globulin if warranted.

Lifestyle Measures for Hepatitis A Prevention. Frequent handwashing after using the bathroom or changing diapers is important for preventing transmission of hepatitis A. International travelers to developing countries should use bottled or boiled water for brushing teeth and drinking, and avoid ice cubes. It is best to eat only well-cooked heated food and to peel raw fruits and vegetables.

Prevention of Hepatitis B

Vaccination. Hepatitis B is preventable by vaccination. There are several inactivated virus vaccines, including Recombivax HB and Engerix-B. A combination vaccine (Twinrix) that contains Engerix-B and Havrix, a hepatitis A vaccine, is also available. The hepatitis B vaccine is usually given as a series of 3 - 4 shots over a 6-month period.

The CDC recommends hepatitis B vaccination for:

- All children should receive their first dose of hepatitis B vaccine at birth and complete their vaccination series by 6 - 18 months. Children younger than age 19 who were not vaccinated should receive “catch-up” doses.

- People who live in a household with or who have sexual relations with a person with chronic hepatitis B

- People with multiple sex partners

- People who have a sexually transmitted disease

- Men who have sex with men

- People who share drug-injection needles and equipment

- Healthcare workers at risk for exposure to blood

- People with diabetes

- People with end-stage renal disease who are on dialysis (hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis)

- People with chronic liver disease

- People infected with HIV

- Residents and staff of institutions for the developmentally disabled

- Travelers to regions that have moderate-to-high rates of hepatitis B infection

Prevention After Exposure to Hepatitis B. The hepatitis B vaccine or a hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG) shot may help prevent hepatitis B infection if given within 24 hours of exposure.

Lifestyle Measures for Hepatitis B Prevention. The following are some precautions for preventing the transmission of hepatitis B (and hepatitis C):

- Use a condom and practice safe sex.

- Avoid sharing personal items such as razors or toothbrushes.

- Do not share drug needles or other drug paraphernalia (such as straws for snorting drugs).

- Clean blood spills with a solution containing 1 part household bleach to 10 parts water.

Hepatitis B (and hepatitis C) viruses cannot be spread by casual contact such as holding hands, sharing eating utensils or drinking glasses, breastfeeding, kissing, hugging, coughing or sneezing.

Prevention of Hepatitis C

There is no vaccine for hepatitis C prevention. Lifestyle precautions are similar to those for hepatitis B. People who are infected with the hepatitis C virus should avoid drinking alcohol as this can accelerate the liver damage associated with hepatitis C. People who are infected with hepatitis C should also receive vaccinations for hepatitis A and B.

Prognosis

Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A is the least serious of the common hepatitis viruses. It only has an acute (short term) form that can last from several weeks to up to 6 months. It does not have a chronic form. Most people who have hepatitis A recover completely. Once people recover, they are immune to the hepatitis A virus.

In very rare cases, hepatitis A can cause liver failure (fulminant hepatic failure) but this usually occurs in people who already have other chronic liver diseases, such as hepatitis B or C.

Hepatitis B

Hepatitis B can have an acute or chronic form. The vast majority (95%) of people who are infected with hepatitis B recover within 6 months and develop immunity to the virus. People who develop immunity are not infectious and cannot pass the virus on to others. Still, blood banks will not accept donations from people who test positive for the presence of HBV antibodies.

About 5% of people develop a chronic form of hepatitis B. People who have chronic hepatitis B remain infectious and are considered carriers of the disease, even if they do not have any symptoms.

Chronic hepatitis B infection significantly increases the risk for liver damage, including cirrhosis and liver cancer. In fact, hepatitis B is the leading cause of liver cancer worldwide. Liver disease, especially liver cancer, is the main cause of death in people with chronic hepatitis B.

Patients with hepatitis B who are co-infected with hepatitis D may develop a more severe form of acute infection than those who have only hepatitis B. Co-infection with hepatitis B and D increases the risk of developing acute liver failure. Patients with chronic hepatitis B who develop chronic hepatitis D also face high risk for cirrhosis. Hepatitis D occurs only in people who are already infected with hepatitis B.

Hepatitis C

Hepatitis C has an acute and chronic form but most people (75 - 85%) who are infected with the virus develop chronic hepatitis C. Chronic hepatitis C poses a risk for cirrhosis, liver cancer, or both.

- About 60 - 70% of patients with chronic hepatitis C eventually develop chronic liver disease.

- About 5 - 20% of patients with chronic hepatitis C develop cirrhosis over a period of 20 - 30 years. The longer the patient has had the infection, the greater the risk. Patients who have had hepatitis C for more than 60 years have a 70% chance of developing cirrhosis.

- Of these patients, about 4% eventually develop liver cancer. (Liver cancer rarely develops without cirrhosis first being present.)

- About 1 - 5% of people with chronic hepatitis C eventually die from cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Patients with chronic hepatitis C may also be at higher risk for non-liver disorders, including:

- Cryoglobulinemia (a disorder in which protein clumps form in the blood). This can cause skin rash and ulcers, kidney problems, arthritis, and sensations (such as tingling or pain) in the hands and feet. People with such symptoms may have particular difficulties with interferon, which can have similar side effects.

- Porphyria cutanea tarda (a disorder that causes skin color and texture changes and sensitivity to light)

- Type 2 diabetes, particularly among younger people with hepatitis C who are overweight

- Glomerulonephritis, a kidney disease caused by inflammation of the kidney

- Certain types of lymphomas (cancers of the lymphatic system), such as non-Hodgkin's lymphoma

Symptoms

Symptoms of Hepatitis A

Symptoms are usually mild, especially in children, and generally appear between 2 - 6 weeks after exposure to the virus. Adult patients are more likely to have fever, jaundice, nausea, fatigue, and itching that can last up to several months. Stools may appear chalky grey and urine will appear darkened.

Symptoms of Hepatitis B

Acute Hepatitis B. Many people with acute hepatitis B have few or no symptoms. If symptoms appear, they tend to occur 6 weeks to 6 months (most commonly 3 months) after exposure and be mild and flu-like. Symptoms may include mild fever, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, fatigue, or muscle or joint aches. Some patients develop dark urine and jaundice (yellowish tinge to skin).

Symptoms of acute hepatitis B can last from a few weeks to 6 months. Even if people infected with hepatitis B have no symptoms, they can still spread the virus.

Chronic Hepatitis B. While some people with chronic hepatitis B have symptoms similar to those of the acute form, many people can have the chronic form for decades and show no symptoms. Liver damage may eventually be detected when blood tests for liver function are performed (see Diagnosis section). [For more information, see In-Depth Report #75: Cirrhosis.]

Symptoms of Hepatitis C

Most patients with hepatitis C do not experience symptoms. Chronic hepatitis C can be present for 10 - 30 years, and cirrhosis or liver failure can sometimes develop before patients experience any clear symptom. Signs of liver damage may first be detected when blood tests for liver function are performed.

If initial symptoms do occur, they tend to be very mild and resemble the flu with fatigue, nausea, loss of appetite, fever, headaches, and abdominal pain. People who have symptoms usually tend to experience them about 6 - 7 weeks after exposure to the virus. Some people may not experience symptoms for up to 6 months after exposure. People who have hepatitis C can still pass the virus on to others even if they do not have symptoms.

Diagnosis

Doctors diagnose hepatitis based on a physical examination and the results of blood tests. In addition to specific tests for hepatitis antibodies, doctors will order other types of blood tests to evaluate liver function.

Specific Tests for Hepatitis A

Blood tests are used to identify IgM anti-HAV antibodies, substances that the body produces to fight hepatitis A infection.

Specific Tests for Hepatitis B

There are many different blood tests for detecting the hepatitis B virus. Standard tests include:

- Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). A positive result indicates active infection, either acute or chronic.

- Antibody to HBsAg (Anti-HBs). A positive result indicates an immune response to hepatitis B, either from previous infection with the virus or from having received the vaccine.

- Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (Anti-HBc). A positive result indicates either recent infection or previous infection.

- Hepatitis B envelope antigen (HBeAg) indicates that someone with a chronic infection is actively contagious.

- Antibody to HBeAg (Anti-HBeAg) usually indicates recovery from chronic hepatitis.

- Hepatitis B DNA (HBV DNA) detects hepatitis B viral genetic material. It can detect an active HBV infection. It is primarily used to monitor response to antiviral treatment in patients with chronic hepatitis B.

Specific Tests for Hepatitis C

Tests to Identify the Virus. The standard first test for diagnosing hepatitis C is an enzyme immunoassay (EIA), which is used to test for hepatitis C antibodies. Antibodies can usually be detected by EIA 4 - 10 weeks after infection.

Tests to Identify Genetic Types and Viral Load. Additional tests called hepatitis C virus RNA assays may be used to confirm the diagnosis. They use a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to detect the RNA (the genetic material) of the virus. Such tests should be used if EIA results show positive HCV antibody and may be performed if there is some doubt about a diagnosis but the doctor still believes the virus is present. HCV RNA can be detected through blood tests as early as 2 - 3 weeks after infection.

Hepatitis C RNA assays also determine virus levels (called viral load). Such levels do not reflect the severity of the condition or speed of progression, as they do for other viruses, such as HIV. However, high viral loads may suggest a poorer response to treatment with interferon drugs.

Patients with detectable viral loads should have HCV genotyping performed. Knowing the specific genotype of the virus is helpful in determining a treatment approach. There are six main genetic types of hepatitis C and more than 50 subtypes. They do not appear to affect the rate of progression of the disease itself, but they can differ significantly in their effects on response to treatment.

Specific genotypes vary in prevalence around the world. Genotype 1 is the most difficult to treat and is the cause of up to 75% of the cases in the U.S. The other common genetic types in the U.S. are types 2 (15%) and 3 (7%), which are more responsive to treatment than genotype 1. People with hepatitis C need to have their genotype tested so that doctors can make appropriate treatment recommendations. Researchers are working on developing a genetic test to identify which patients with chronic hepatitis C are most at risk of developing cirrhosis.

Liver Biopsy. Liver biopsy may be helpful both for diagnosis and for determining treatment decisions. Only a biopsy can determine the extent of injury in the liver. Some doctors recommend biopsies only for patients who do not have genotypes 2 or 3 (as these genotypes tend to respond well to treatment). A liver biopsy in patients with other genotypes may help clarify risk for disease progression and allow doctors to reserve treatment for patients with moderate-to-severe liver scarring (fibrosis). Even in patients with normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) liver enzyme levels, a liver biopsy can reveal significant damage.

Tests for Liver Function

In people suspected of having or carrying viral hepatitis, doctors will measure certain substances in the blood.

- Bilirubin. Bilirubin is one of the most important factors indicative of hepatitis. It is a red-yellow pigment that is normally metabolized in the liver and then excreted in the urine. In patients with hepatitis, the liver cannot process bilirubin, and blood levels of this substance rise. (High levels of bilirubin cause the yellowish skin tone known as jaundice.)

- Liver Enzymes (Aminotransferases). Enzymes known as aminotransferases, including aspartate (AST) and alanine (ALT), are released when the liver is damaged. Measurements of these enzymes, particularly ALT, are the most important tests for detecting hepatitis and monitoring treatment effectiveness. Enzyme levels vary, however, and are not always an accurate indicator of disease activity. (For example, they are not useful in detecting progression to cirrhosis.)

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP). High ALP levels can indicate bile duct blockage.

- Serum Albumin Concentration. Serum albumin measures protein in the blood (low levels indicate poor liver function).

- Prothrombin Time (PT). The PT test measures in seconds the time it takes for blood clots to form (the longer it takes the greater the risk for bleeding).

Liver Biopsy

A liver biopsy may be performed for acute viral hepatitis caught in a late stage or for severe cases of chronic hepatitis. A biopsy helps determine treatment possibilities, the extent of damage, and the long-term outlook.

A biopsy involves a doctor inserting a biopsy fine needle, guided by ultrasound, to remove a small sample of liver tissue. Local anesthetic is used to numb the area. Patients may feel pressure and some dull pain. The procedure takes about 20 minutes to perform.

Treatment

Treatment for Hepatitis A

Hepatitis A usually clears up on its own and does not require treatment. Patients should make sure to get plenty of rest and avoid drinking any alcohol until they are fully recovered.

Treatment for Hepatitis B

There are no medications for treating acute hepatitis B. Doctors usually recommend that patients get plenty of bed rest, drink plenty of fluids, and get adequate nutrition.

Many types of antiviral drugs are available to treat chronic hepatitis B. Not all patients with chronic hepatitis B require medication. Patients should seek the advice of an internal medicine doctor (internist) or another specialist (a gastroenterologist, hepatologist, or infectious disease doctor) who has experience treating hepatitis B.

Patients with chronic hepatitis B should receive regular monitoring to evaluate any signs of disease progression, liver damage, or liver cancer. It is also important that patients with chronic hepatitis B abstain from alcohol as it may accelerate liver damage. Patients should check with their doctors before taking any over-the-counter or prescription medications or herbal supplements. Some medications (such as high doses of acetaminophen) and herbal products (kava) can increase the risk of liver damage.

If the disease progresses to liver failure, liver transplantation may be an option. It is not foolproof, however. In patients with hepatitis B, the virus often recurs in the new liver after transplantation. However, regular, lifelong injections of hepatitis B immune globulin (HepaGam B) can reduce the risk for re-infection following liver transplantation.

Treatment for Hepatitis C

Antiviral drug therapy is used to treat both acute and chronic forms of hepatitis C. Most people infected with hepatitis C virus develop the chronic form of the disease. The standard treatment for chronic hepatitis C is dual combination therapy with the antiviral drugs pegylated interferon and ribavirin. For patients with genotype 1 HCV, a protease inhibitor drug (telaprevir or boceprevir) may be added to this combination for triple therapy. These new drugs have significantly improved cure rates.

Other types of drugs may also be used. Doctors will generally recommend drug treatment unless there are medical contraindications to it. (See "Candidates for Interferon Treatment" in Medications section.) Research shows that patients with chronic hepatitis C receive the best care when they are treated by a team that includes both a primary care doctor and a hepatitis specialist doctor.

Patients with chronic hepatitis C should receive genotype testing to determine the treatment approach. There are six types of hepatitis C genotypes and patients have different responses to drugs depending on their genotype. For example, patients with genotypes 2 or 3 are three times more likely to respond to treatment than patients with genotype 1. The recommended course of duration of treatment also depends on genotype. Patients with genotype 2 or 3 usually have a 24-week course of treatment whereas a 48-week course is recommended for patients with genotype 1.

Patients are considered cured when they have had a “sustained virologic response” and there is no evidence of hepatitis C on lab testing. A sustained virologic response (SVR) means that the hepatitis C virus becomes undetectable during treatment and remains undetectable for at least six months after treatment has been completed. A SVR indicates that the treatment was successful and that the patient has been cured of hepatitis C. For most patients who have a response, viral loads remain undetectable indefinitely. However, some patients can become re-infected or infected with a different genotype strain.

Patients who develop cirrhosis or liver cancer from chronic hepatitis C may be candidates for liver transplantation. Unfortunately, hepatitis C usually recurs after transplantation, which can lead to cirrhosis of the new liver in at least 25% of patients 5 years after transplantation. The issue of retransplantation for patients with recurrent hepatitis C is a matter of debate.

Patients with chronic hepatitis C should abstain from alcohol as it can speed cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease. Patients should also check with their doctors before taking any non-prescription or prescription medications, or herbal supplements. It is also important that patients who are infected with HCV be tested for HIV, as patients who have both HIV and HCV have a more rapid progression of liver disease than those who have HCV alone.

Herbal Remedies and Liver Disease

Popular herbal remedies for hepatitis include ginseng, glycyrrhizin (a compound in licorice), catechin (found in green tea), and silymarin (found in milk thistle). However, there is no evidence that these herbs are helpful for hepatitis or other liver diseases.

Milk thistle is the most studied of these herbs and evidence of its benefit has been mixed. Some small older studies indicated that milk thistle may help improve liver enzyme levels. However, recent rigorous reviews and better designed studies have found that the herb is ineffective for treating liver disease caused by hepatitis B or C.

Patients with hepatitis should be aware that some herbal remedies may cause liver damage. In particular, kava (an herb promoted to relieve anxiety and tension) is dangerous for people with chronic liver disease. Other herbs associated with liver damage include chaparral, kombucha mushroom, mistletoe, pennyroyal, and some traditional Chinese herbs.

Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation may be indicated for patients with severe cirrhosis or for patients with liver cancer that has not spread beyond the liver.

Current 5-year survival rates after liver transplantation are 55 - 80%, depending on different factors. Patients report improved quality of life and mental functioning after liver transplantation.

Patients should consider medical centers that have performed more than 50 transplants per year and produced better-than-average results. Unfortunately, there are far more people waiting for liver transplants than there are available organs. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #75: Cirrhosis.]

Medications

Medications for Chronic Hepatitis B

Seven drugs are currently approved in the United States for treatment of chronic hepatitis B:

- Peginterferon alfa-2a (Pegasys)

- Interferon-alfa-2b (Intron A)

- Lamivudine (Epivir-HBV)

- Entecavir (Baraclude)

- Telbivudine (Tyzeka)

- Adefovir (Hepsera)

- Tenofovir (Viread)

These drugs block the replication of hepatitis B in the body. They may also help prevent the development of progressive liver disease (cirrhosis and liver failure) and the development of liver cancer.

A doctor will decide which drug to prescribe based on a patient's age, disease severity, and other factors. A combination of drugs may also be prescribed. Peginterferon alfa-2a, entecavir, and tenofovir are the preferred drugs for first-line, long-term treatment.

It is not always clear which patients with chronic hepatitis B should receive drug therapy and when drug therapy should be started. Therapy is generally indicated for patients who have experienced a rapid deterioration in liver function, or patients with cirrhosis complications such as ascites and hemorrhage. [For more information on complications of cirrhosis, see In-Depth Report #75: Cirrhosis.]

Patients who are receiving immunosuppressive therapy for other medical conditions or who have had reactivation of chronic hepatitis B are also appropriate candidates.

Peginterferon alfa-2a. Peginterferon alfa-2a (Pegasys) was approved in 2005 for treatment of chronic hepatitis B. (Peginterferon is also called pegylated interferon.) This drug prevents the hepatitis B virus from replicating and also helps boost the immune system. It is given as a weekly injection. Peginterferon is sometimes prescribed in combination with lamivudine (Epivir-HBV).

Common side effects include flu-like symptoms, such as fever, chills, muscle aches, joint pains, and headaches. The drug can also cause depression, anxiety, irritability, and insomnia and should be used with caution in patients with a history of mental illness. Peginterferon alfa-2a can also increase the risk for infections, and worsening of hepatitis as marked by sudden severe increases in ALT levels. Patients who show signs of ALT flares should have frequent blood tests to monitor their liver function.

Unlike other drugs used to treat chronic hepatitis B, drug resistance is less of a problem with peginterferon alfa-2a.

Interferon Alfa-2b. For many years, interferon alfa-2b (Intron A) was the standard drug for hepatitis B. It is now generally second line to peginterferon The drug is usually taken by injection every day for 16 weeks. Unfortunately, the hepatitis B virus recurs in almost all cases, although this recurring mutation may be weaker than the original strain. Administering the drug for longer periods may produce sustained remission in more patients while still being safe. Interferon is also effective in eligible children, although long-term effects are unclear. Like peginterferon alfa-2a, this drug can increase the risk of depression.

Lamivudine, Entecavir, and Telbivudine. These drugs are classified as nucleoside analogs. Lamivudine (Epivir-HBV) is also used in another formulation to treat human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). About 20% of patients who take lamivudine develop drug resistance. Lamivudine, along with interferon alfa-2b, are the only drugs approved for treatment of chronic hepatitis B in children. Entecavir (Baraclude) and telbivudine (Tyzeka) are approved for treatment of adults with chronic hepatitis B.

If patients develop resistance to one of these nucleoside analog drugs, a nucleotide-analog drug such as adefovir or tenofovir may be added as combination therapy. Lamivudine is associated with the highest rate of drug resistance. Entecavir and tenofovir have the lowest likelihood of drug resistance.

Common side effects of these drugs include headache, fatigue, dizziness, and nausea. (For more serious side effects, see "Drug Complications and Warnings" below.)

Adefovir and Tenofovir. Adefovir (Hepsera) is an older drug that belongs to a class of antiviral drugs called nucleotide analogs. Nucleotide analogs block an enzyme involved in the replication of viruses. Tenofovir (Viread) is a newer nucleotide analog drug that is now preferred over adefovir. These drugs are effective against lamivudine-resistant strains of hepatitis B. Common side effects of these drugs include weakness, headache, stomach pain, and itching.

Drug Complications and Warnings for Nucleoside/Nucleotide Analog Drugs. Patients who discontinue anti-HBV drug therapy are at risk for severe and sudden worsening of hepatitis. These patients should be closely monitored for several months after stopping treatment. If necessary, drug treatment may need to be reinstated.

Lactic acidosis (buildup of acid in the blood) is a serious complication of nucleoside/nucleotide analog drugs. Signs and symptoms of lactic acidosis include feeling extremely tired, unusual muscle pain, difficulty breathing, stomach pain with nausea and vomiting, feeling cold (especially in the arms and legs), feeling dizzy or light-headed, or a fast or irregular heartbeat. Immediately contact your doctor if you experience these symptoms.

Liver hepatotoxicity (liver damage) is another serious complication. Signs and symptoms include yellowing of skin or white part of eyes (jaundice), dark urine, light-colored stool, or lower stomach pain. Immediately contact your doctor if you experience these symptoms.

These drugs may also cause kidney damage (nephrotoxicity), particularly for people who already have kidney function problems.

Medications for Chronic Hepatitis C

Pegylated interferon combined with the nucleoside analog drug ribavirin (Copegus) is the gold standard treatment for chronic hepatitis C in both adults and children. For patients with hepatitis C genotype 1, this combination treatment lasts 48 weeks. A newer treatment plan that adds a protease inhibitor drug to the two older medication produces better results in as little as 24 weeks (see below).

Patients with hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 who do not have cirrhosis usually have 24 weeks of pegylated interferon-ribavirin treatment. This drug combination cures up to 70% of patients infected with genotypes 2 or 3 but only about 45% of patients infected with hepatitis C genotype 1 (the most common genotype form in the U.S.).

Pegylated interferon is given as an injection once a week. Ribavirin is taken as a pill twice a day. Pegyated interferon alone is usually reserved for patients who cannot tolerate ribavirin

Two types of pegylated interferon are available for chronic hepatitis C treatment:

- Peginterferon alfal-2a (Pegasys)

- Peginterferon alfa-2b (Peg-Intron)

Candidates for Treatment. While all patients with chronic hepatitis C are potential candidates for treatment, doctors usually decide whether treatment is appropriate based on many different factors.

Treatment is generally recommended for patients with chronic hepatitis C who are at least 18 years old and have:

- Detectable virus levels as measured by an HCV RNA test

- An increased risk of developing cirrhosis

- Indication of liver scarring (fibrosis) as detected by liver biopsy

- Abnormal levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), an indication of liver cell damage

Treatment is generally not recommended for people who have:

- Advanced cirrhosis or liver cancer

- Major uncontrolled depression, particularly if they have attempted suicide in the past

- Autoimmune hepatitis or other autoimmune disorders such as hyperthyroidism

- Received bone marrow, lung, heart, or kidney organ transplantation

- Severe high blood pressure, coronary artery disease, heart failure, kidney disease, or other serious non-liver disorders that may affect life expectancy

- Severe anemia (low red blood cell count) or thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count)

- Women who are pregnant or who do not use birth control

- Patients who actively abuse drugs or alcohol may not be appropriate candidates.

Side Effects of Treatment. Side effects of combination treatment include those caused by both pegylated interferon and ribavirin.

Side effects and complications of pegylated interferon include:

- Fatigue

- Flu-like symptoms (such as fever, chills, and muscle aches)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Headaches

- Weight loss

- Irritability

- Depression

- Hair thinning

- Bone marrow suppression

- Soreness at the injection site

- Serious infections

Side effects and complications of ribavirin include:

- Anemia, which can worsen heart disease

- Fatigue

- Severe itching

- Rash

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

- Birth defects

New Drugs for Chronic Hepatitis C: Telaprevir and Boceprevir. The standard drug therapy for chronic hepatitis C (peginterferon alfa and ribavirin) is not effective for half of the patients with genotype 1. In 2011, the FDA approved two new drugs to treat adult patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C.

Telaprevir (Incivek) and boceprevir (Victrelis) belong to a class of drugs called protease inhibitors, which work by preventing the virus from multiplying. Neither telaprevir nor boceprevir can be used alone. Either one must be used in combination with both peginterferon alfa and ribavirin.

In clinical trials, the three-drug combination cured hepatitis C in about 75% of patients who took telaprevir and about 67% of patients who took boceprevir. In contrast, only 45% of patients with genotype 1 are successfully treated by peginterferon alfa and ribavirin combination therapy. Patients who respond well to the triple combination may be able to stop at 24 weeks instead of having the full 48-week course of treatment.

Genotype 1 is the most common type of hepatitis C and is more difficult to treat than genotypes 2 and 3, so the introduction of these new drugs represents a real breakthrough for hepatitis C treatment. However, the peginterferon and ribavirin regimen is very expensive and these new drugs add additional substantial costs to treatment.

Telaprevir and boceprevir are taken as pills three times a day. The most serious side effect is increased risk of anemia. Other side effects associated with these medications include nausea, diarrhea, headache, and fatigue. Rash can also be a serious side effect of telaprevir.

Telaprevir and boceprevir can also:

- Increase the risks of birth defects or death of unborn baby. These drugs can prevent hormonal contraceptives (birth control pills, vaginal rings, implants, injections) from working well. Patients (both men and women) who take telaprevir or boceprevir should use two non-hormonal forms of contraception during treatment and for six months after treatment.

- Interact with many types of medications including statin drugs, anti-seizure drugs, and drugs used to treat HIV. Make sure your doctor knows all medications or herbal supplements you are taking. Herbs such as St. John’s wort should not be taken with these drugs.

- Telaprevir may cause a severe and life-threatening skin rash. Patients must immediately stop telaprevir treatment if they experience this type of rash.

.

Resources

- www.cdc.gov/hepatitis -- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- www.aasld.org -- American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases

- www.hepfi.org -- Hepatitis Foundation International

- www.hepb.org -- Hepatitis B Foundation

- www.liverfoundation.org -- American Liver Foundation

- www2.niddk.nih.gov -- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

- www.unos.org -- United Network for Organ Sharing

References

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: Prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007 Oct 19;56(41):1080-4.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Hepatitis A vaccine recommendations. Pediatrics. 2007 Jul;120(1):189-99.

Bacon BR, Gordon SC, Lawitz E, Marcellin P, Vierling JM, Zeuzem S, et al. Boceprevir for previously treated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 31;364(13):1207-17.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of hepatitis B vaccination for adults with diabetes mellitus: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Dec 23;60(50):1709-11.

Chou R, Cottrell EB, Wasson N, Rahman B, Guise JM. Screening for Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adults: A Systematic Review to Update the 2004 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Nov 27. [Epub ahead of print]

Chou R, Hartung D, Rahman B, Wasson N, Cottrell EB, Fu R. Comparative effectiveness of antiviral treatment for hepatitis C virus infection in adults: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Nov 27. [Epub ahead of print]

Cooke GS, Main J, Thursz MR. Treatment for hepatitis B. BMJ. 2010 Jan 5;340:b5429. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5429.

Dienstag JL. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2008 Oct 2;359(14):1486-500.

Fried MW, Navarro VJ, Afdhal N, Belle SH, Wahed AS, Hawke RL, et al. Effect of silymarin (milk thistle) on liver disease in patients with chronic hepatitis C unsuccessfully treated with interferon therapy: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2012 Jul 18;308(3):274-82.

Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology. 2009 Apr;49(4):1335-74.

Jensen DM. A new era of hepatitis C therapy begins. N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 31;364(13):1272-4.

Jacobson IM, McHutchison JG, Dusheiko G, Di Bisceglie AM, Reddy KR, Bzowej NH, et al. Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 23;364(25):2405-16.

Kanwal F, Schnitzler MS, Bacon BR, Hoang T, Buchanan PM, Asch SM. Quality of care in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010 Aug 17;153(4):231-9.

Ly KN, Xing J, Klevens RM, Jiles RB, Ward JW, Holmberg SD. The increasing burden of mortality from viral hepatitis in the United States between 1999 and 2007. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Feb 21;156(4):271-8.

Maheshwari A, Ray S, Thuluvath PJ. Acute hepatitis C. Lancet. 2008 Jul 26;372(9635):321-32.

Mukherjee S, Sorrell MF. Controversies in liver transplantation for hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2008 May;134(6):1777-88.

Poordad F, McCone J Jr, Bacon BR, Bruno S, Manns MP, Sulkowski MS, et al. Boceprevir for untreated chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2011 Mar 31;364(13):1195-206.

Rosen HR. Clinical practice. Chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 23;364(25):2429-38.

Rambaldi A, Jacobs BP, Gluud C. Milk thistle for alcoholic and/or hepatitis B or C virus liver diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD003620.

Scott JD, Gretch DR. Molecular diagnostics of hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007 Feb 21;297(7):724-32.

Smith BD, Morgan RL, Beckett GA, Falck-Ytter Y, Holtzman D, Teo CG, et al. Recommendations for the identification of chronic hepatitis C virus infection among persons born during 1945-1965. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012 Aug 17;61(RR-4):1-32.

Sorrell MF, Belongia EA, Costa J, Gareen IF, Grem JL, Inadomi JM, et al. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Conference Statement:management of hepatitis B. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jan 20;150(2):104-10. Epub 2009 Jan 5.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for hepatitis B virus infection in pregnancy: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009 Jun 16;150(12):869-73, W154.

Victor JC, Monto AS, Surdina TY, Suleimenova SZ, Vaughan G, Nainan OV, et al. Hepatitis A vaccine versus immune globulin for postexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med. 2007 Oct 25;357(17):1685-94. Epub 2007 Oct 18.

Weinbaum CM, Williams I, Mast EE, Wang SA, Finelli L, Wasley A, et al. Recommendations for identification and public health management of persons with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008 Sep 19;57(RR-8):1-20.

Woo G, Tomlinson G, Nishikawa Y, Kowgier M, Sherman M, Wong DK, et al. Tenofovir and entecavir are the most effective antiviral agents for chronic hepatitis B: a systematic review and Bayesian meta-analyses. Gastroenterology. 2010 Oct;139(4):1218-29. Epub 2010 Jun 20.

Zeuzem S, Andreone P, Pol S, Lawitz E, Diago M, Roberts S, et al. Telaprevir for retreatment of HCV infection. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 23;364(25):2417-28.

|

Review Date:

12/26/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, In-Depth Reports; Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |