Herpes simplex

Highlights

Herpes Viruses

- Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is the main cause of herpes infections that occur on the mouth and lips. These include cold sores and fever blisters. HSV-1 can also cause genital herpes.

- Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) is the main cause of genital herpes.

Transmission of Genital Herpes

Genital herpes is spread by sexual activity through skin-to-skin contact. The risk of infection is highest during outbreak periods when there are visible sores and lesions. However, genital herpes can also be transmitted when there are no visible symptoms. Most new cases of genital herpes infection do not cause symptoms, and many people infected with HSV-2 are unaware that they have genital herpes.

To help prevent genital herpes transmission:

- Use a latex condom for sexual intercourse

- Use a dental dam for oral sex

- Limit your number of sexual partners

- Be aware that nonoxynol-9, the chemical spermicide used in gel and foam contraceptive products and some lubricated condoms, does not protect against any sexually transmitted diseases.

Symptoms

When genital herpes symptoms do appear, they are usually worse during the first outbreak than during recurring attacks. During an initial outbreak:

- Symptoms usually appear within 1 - 2 weeks after sexual exposure to the virus.

- The first signs are a tingling sensation in the affected areas, (genitalia, buttocks, thighs), and groups of small red bumps that develop into blisters.

- Over the next 2 - 3 weeks, more blisters can appear and rupture into painful open sores.

- The lesions eventually dry out and develop a crust, and then heal rapidly without leaving a scar.

- About 40% of men and 70% of women develop flu-like symptoms during initial outbreaks of genital herpes, such as headache, muscle aches, fever, and swollen glands.

Introduction

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) commonly causes infections of the skin and mucous membranes. Sometimes it can cause more serious infections in other parts of the body.

HSV is part of a group of other herpes viruses that include human herpes virus 8 (the cause of Kaposi's sarcoma) and varicella- zoster virus (also known as herpes zoster, the virus responsible for shingles and chicken pox). There are more than 80 types of herpes viruses. They differ in many ways, but the viruses share certain characteristics, notably the word "herpes," which is derived from a Greek word meaning "to creep." This refers to the unique characteristic pattern of all herpes viruses to "creep along" local nerve pathways to the nerve clusters at the end, where they remain in an inactive state for variable periods of time.

There are two forms of the herpes simplex virus:

- Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1)

- Herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2)

These viruses are distinguished by different proteins on their surfaces. They can occur separately, or they can both infect the same individual. Until recently, the general rule was to assume that HSV-1 infections occur in the oral cavity (mouth) and are not sexually transmitted, while HSV-2 attacks the genital area and is sexually transmitted. It is now widely accepted, however, that either type can be found in either area and at other sites. In fact, HSV-1 is now responsible for up to half of all new cases of genital herpes in developed countries.

The Disease Process

For infection to occur, the following conditions must apply:

- The herpes simplex virus passes through bodily fluids (such as saliva, semen, or fluid in the female genital tract) or in fluid from a herpes sore.

- The virus must have direct access to the uninfected person through their skin or mucous membranes (such as in the mouth or genital area).

When herpes simplex virus enters the body, the infection process typically takes place as follows:

- The virus enters vulnerable cells in the lower layers of skin tissue and tries to reproduce in the cell nuclei.

- Even after it has entered the cells, the virus usually does not cause symptoms.

- However, if the virus destroys the host cells when it multiplies, inflammation and fluid-filled blisters or ulcers appear. Once the fluid is absorbed, scabs form, and the blisters disappear without scarring.

- After the first time they multiply, the viral particles are carried from the skin through branches of nerve cells to clusters at the nerve-cell ends (the dorsal root ganglia).

- Here, the virus lives in an inactive (latent) form. The virus does not multiply, but both the host cells and the virus survive.

- At unpredictable times, the virus begins multiplying again. It then goes through a stage called shedding. During those times, the virus can be passed into bodily fluids and infect other people. Unfortunately, a third to half of the times shedding occurs without any symptoms at all.

- Eventually, the symptoms return in most cases, causing a new outbreak of blisters and sores.

Transmission

To infect people, the herpes simplex viruses (both HSV-1 and HSV-2) must get into the body through tiny injuries in the skin or through a mucous membrane, such as inside the mouth or on the genital area. Both viruses can be carried in bodily fluids (such as saliva, semen, or fluid in the female genital tract) or in fluid from herpes sores. The risk for infection is highest with direct contact of blisters or sores during an outbreak.

Once the virus has contact with the mucous membranes or skin wounds, it begins to replicate. The virus is then transported within nerve cells to their roots where it remains inactive (latent) for some period of time. During inactive periods, the virus cannot be transmitted to another person. However, at some point, it often begins to multiply again without causing symptoms (called asymptomatic shedding). During shedding, the virus can infect other people through exchange of bodily fluids.

Sometimes, infected people can transmit the virus and infect other parts of their own bodies (most often the hands, thighs, or buttocks). This process, known as autoinoculation, is uncommon, since people generally develop antibodies that protect against this problem.

Transmission of Oral Herpes. Oral herpes is usually caused by HSV-1. HSV-1 is the most prevalent form of herpes simplex virus, and infection is most likely to occur during preschool years. Oral herpes is easily spread by direct exposure to saliva or even from droplets in breath. Skin contact with infected areas is enough to spread it. Transmission most often occurs through close personal contact, such as kissing. In addition, because herpes simplex virus 1 can be passed in saliva, people should also avoid sharing toothbrushes or eating utensils with an infected person.

Transmission of Genital Herpes. Genital herpes is most often transmitted through sexual activity, and people with multiple sexual partners are at high risk. The virus, however, can also enter through the anus, skin, and other areas.

People with active symptoms of genital herpes are at very high risk for transmitting the infection. Unfortunately, evidence suggests about a third of all herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) infections occur when the virus is shedding but producing no symptoms. Most people either have no symptoms or don't recognize them when they appear.

In the past, genital herpes was mostly caused by HSV-2, but HSV-1 genital infection is increasing. This may be due to the increase in oral sex activity among young adults.

Symptoms

Symptoms vary depending on whether the outbreak is initial or recurrent. The first (primary) outbreak is usually worse than recurrent outbreaks. However, most cases of new herpes simplex virus infections do not produce symptoms. In fact, studies indicate that 10 - 25% of people infected with HSV-2 are unaware that they have genital herpes. Even if infected people have mild or no symptoms, they can still transmit the herpes virus.

Symptoms of Genital Herpes

Primary Genital Herpes Outbreak. For patients with symptoms, the first outbreak usually occurs in or around the genital area 1 - 2 weeks after sexual exposure to the virus. The first signs are a tingling sensation in the affected areas (such as genitalia, buttocks, and thighs) and groups of small red bumps that develop into blisters. Over the next 2 - 3 weeks, more blisters can appear and rupture into painful open sores. The lesions eventually dry out, develop a crust, and heal rapidly without leaving a scar. Blisters in moist areas heal more slowly than others. The lesions may sometimes itch, but itching decreases as they heal.

About 40% of men and 70% of women develop other symptoms during initial outbreaks of genital herpes, such as flu-like discomfort, headache, muscle aches, fever, and swollen glands. (Glands can become swollen in the groin area as well as the neck.) Some patients may have difficulty urinating, and women may experience vaginal discharge.

Recurrent Genital Herpes Outbreak. In general, recurrences are much milder than the initial outbreak. The virus sheds for a much shorter period of time (about 3 days) compared to in an initial outbreak of 3 weeks. Women may have only minor itching, and the symptoms may be even milder in men.

On average, people have about four recurrences during the first year, although this varies widely. Over time, recurrences decrease in frequency. There are some differences in frequency of recurrence depending on whether HSV-2 or HSV-1 causes genital herpes. HSV-2 genital infection is more likely to cause recurrences than HSV-1.

Symptoms of Oral Herpes

Oral herpes (herpes labialis) is most often caused by herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) but can also be caused by herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2). It usually affects the lips and, in some primary attacks, the mucous membranes in the mouth. A herpes infection may occur on the cheeks or in the nose, but facial herpes is very uncommon.

Primary Oral Herpes Infection. If the primary (initial) oral infection causes symptoms, they can be very painful, particularly in small children.

- Blisters form on the lips but may also erupt on the tongue.

- The blisters eventually rupture as painful open sores, develop a yellowish membrane before healing, and disappear within 3 - 14 days.

- Increased salivation and bad breath may be present.

- Rarely, the infection may be accompanied by difficulty in swallowing, chills, muscle pain, or hearing loss.

In children, the infection usually occurs in the mouth. In adolescents, the primary infection is more apt to appear in the upper part of the throat and cause soreness.

Recurrent Oral Herpes Infection. Most patients have only a couple of outbreaks a year, although a small percentage of patients have more frequent recurrences. HSV-2 oral infections tend to recur less frequently than HSV-1. Recurrences are usually much milder than primary infections and are known commonly as cold sores or fever blisters (because they may arise during a bout of cold or flu). They usually show up on the outer edge of the lips and rarely affect the gums or throat. (Cold sores are commonly mistaken for the crater-like mouth lesions known as canker sores, which are not associated with herpes simplex virus.)

Recurrence Course, Triggers, and Timing

Course of Recurrence. Most cases of herpes simplex recur. The site on the body and the type of virus influence how often it comes back. The virus usually takes the following course:

- Prodrome. The outbreak of infection is often preceded by a prodrome, an early group of symptoms that may include itching skin, pain, or an abnormal tingling sensation at the site of infection. The patient may also have a headache, enlarged lymph glands, and flu-like symptoms. The prodrome, which may last as short as 2 hours or as long as 2 days, stops when the blisters develop. About 25% of the time, recurrence does not go beyond the prodrome stage.

- Outbreak. Recurrent outbreaks feature most of the same symptoms at the same sites as the primary attack, but they tend to be milder and briefer. After blisters erupt, they typically heal in 6 - 10 days. Occasionally, the symptoms may not resemble those of the primary episode but appear as fissures and scrapes in the skin or as general inflammation around the affected area.

Triggers of Recurrence. HSV outbreaks can be triggered by different factors. They include sunlight, wind, fever, physical injury, surgery, menstruation, suppression of the immune system, and emotional stress. Oral herpes can be triggered within about 3 days of intense dental work, particularly root canal or tooth extraction.

Timing of Recurrences. Recurrent outbreaks may occur at intervals of days, weeks, or years. For most people, outbreaks recur with more frequency during the first year after an initial attack. During that period, the body mounts an intense immune response to HSV. In most healthy people, recurring infections tend to become progressively less frequent, and less severe, over time. However, the immune system cannot kill the virus completely.

Risk Factors

Risk for Oral Herpes

Oral herpes is usually caused by HSV-1. The first infection usually occurs between 6 months and 3 years of age. By adulthood, nearly all people (60 - 90%) have been infected with HSV-1.

Risk for Genital Herpes

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, about 1 in 6 American teenagers and adults, are infected with HSV-2. While HSV-2 remains the main cause of genital herpes, in recent years HSV-1 has significantly increased as a cause, most likely because of oral-genital sex. Except for people in monogamous relationships with uninfected partners, everyone who is sexually active is at risk for genital herpes.

Risk factors for genital herpes include a history of a prior sexually transmitted disease, early age for first sexual intercourse, a high number of sexual partners, and loq socioeconomic status. Women are more susceptible to HSV-2 infection because herpes is more easily transmitted from men to women than from women to men. About 1 in 5 women, compared to 1 in 9 men, have genital herpes. African-American women are at particularly high risk

People with compromised immune systems, notably patients with HIV, are at very high risk for HSV-2. These patients are also at risk for more severe complications from herpes. Other immunocompromised patients include those taking drugs that suppress the immune system and patients who have received transplants.

Risk for Specific Forms of Herpes

The following are examples of people who are at particularly risk for specific forms of herpes.

- Health care providers, including doctors, nurses, and dentists. This group is at higher than average risk for herpetic whitlow, herpes that occurs in the fingers.

- Wrestlers, rugby players, and other athletes who participate in direct contact sports without protective clothing. These individuals are at risk for herpes gladiatorum, an unusual form of HSV-1 that is spread by skin contact with exposed herpes sores and usually affects the head or eyes.

Preventing Transmission

Infected people should take steps to avoid transmitting genital herpes to others. It is almost impossible to defend against the transmission of oral herpes since it can be transmitted by very casual contact.

Genital herpes is contagious from the first signs of tingling and burning (prodrome) until the time that sores have completely healed. It is best to refrain from sex during periods of active outbreak. However, herpes can also be transmitted when symptoms are not present (asymptomatic shedding).

The following precautions can help reduce the risk of transmission:

- Use a latex condom. While condoms may not provide 100% protection, they have been proven to significantly reduce the risk of sexual disease transmission. Condoms made of latex are less likely to slip or break than those made of polyurethane. Natural condoms made from animal skin do NOT protect against HSV infection because herpes viruses can pass through them.

- Use a water-based lubricant. Lubricants can help prevent friction during sex, which can irritate the skin and increase the risk for outbreaks. Only water-based lubricants (such as K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, AquaLube, and glycerin) should be used. Oil-based lubricants (such as petroleum jelly, body lotions, and cooking oil) can weaken latex. Many condoms come pre-lubricated. However, it is best not to use condoms pre-lubricated with spermicides.

- Do not use spermicides for protection against herpes. Some condoms come pre-lubricated with sperm-killing substances called spermicides. Spermicides also come in stand-alone foams and jellies. The standard active ingredient in spermicides is nonoxynol-9. Nonoxynol-9 can cause irritation around the genital areas, which makes it easier for herpes and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) to be transmitted.

- Use a dental dam for oral sex.

- Limit the number of sexual partners.

[For more information, see In-Depth Report # 91: Birth control options for women.]

To reduce the risk of passing the herpes virus to another part of your body (such as the eyes and fingers), avoid touching a herpes blister or sore during an outbreak. If you do, be sure to immediately wash your hands with hot water and soap.

The herpes virus does not live very long outside the body. While the chances of transmitting or contracting herpes from a toilet seat or towel are extremely low, it is advisable to wipe off toilet seats and not to share damp towels.

Recent studies have suggested that male circumcision may help reduce the risk of HSV-2, as well as human papillomavirus (HPV) and HIV infections. However, circumcision does not completely prevent sexually transmitted diseases. Men who are circumcised should still practice safe sex, including using condoms.

Complications

The severity of herpes simplex symptoms depends on where and how the virus enters the body. Except in very rare instances and special circumstances, HSV is not life threatening.

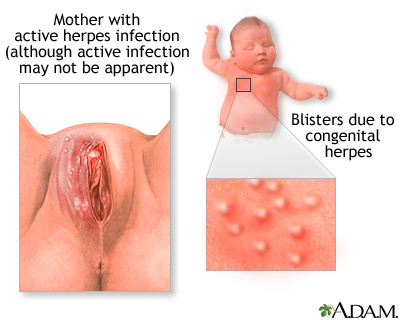

Herpes and Pregnancy

Pregnant women who have genital herpes due to either herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) or herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) have an increased risk for miscarriage, premature labor, retarded fetal growth, or transmission of the herpes infection to the infant either in the uterus or at the time of delivery. Herpes in newborn babies (herpes neonatalis) can be a very serious condition.

Fortunately, neonatal herpes is rare. Although about 25 - 30% of pregnant women have genital herpes, less than 0.1% of babies are born with neonatal herpes. The baby is at greatest risk during a vaginal delivery, especially if the mother has an asymptomatic infection that was first introduced late in the pregnancy. In such cases, 30 - 50% of newborns become infected. Recurring herpes or a first infection that is acquired early in the pregnancy pose a much lower risk to the infant.

The reasons for the higher risk with a late primary infection are:

- During a first infection, the virus is shed for longer periods, and more viral particles are excreted.

- An infection that first occurs in the late term of pregnancy does not allow the mother time to develop antibodies that would help her baby fight off the infection at the time of delivery.

The risk for transmission also increases if infants with infected mothers are born prematurely, if there is invasive monitoring, or if instruments are used during vaginal delivery. Transmission can occur if the amniotic membrane of an infected woman ruptures prematurely, or as the infant passes through an infected birth canal. This increased risk is present if the woman is having or has recently had an active herpes outbreak in the genital area.

Very rarely, the virus is transmitted across the placenta, a form of the infection known as congenital herpes. Also rarely, newborns may contract herpes during the first weeks of life from being kissed by someone with a herpes cold sore.

Unfortunately, only 5% of infected pregnant women have a history of symptoms, so in many cases herpes infection is not suspected, or symptoms are missed, at the time of delivery. If there is evidence of an active outbreak, doctors usually advise a Cesarean section to prevent the baby from contracting the virus in the birth canal during delivery.

Approach to the Pregnant Herpes Patient. The approach to a pregnant woman who has been infected by either HSV-1 or HSV-2 in the genital area is usually determined by when the infection was acquired and the mother's condition around the time of delivery:

- Obtaining routine herpes cultures on all women during the prenatal period is not recommended.

- Tests such as chorionic vilus sampling, amniocentesis, and percutaneous fetal blood draws can safely be performed during pregnancy.

- If necessary, using fetal scalp techniques is considered reasonable if there have been no recent genital herpes outbreaks.

- If lesions in the genital area are present at the time of birth, Cesarean section is usually recommended. (Even a Cesarean section is no guarantee that the child will be virus-free, and the newborn must still be tested.)

- If lesions erupt shortly before the baby is due, the doctor must take samples and send them to the laboratory. Samples are cultured to detect the virus at 3 - 5-day intervals prior to delivery to determine whether viral shedding is occurring. If no lesions are present and cultures indicate no viral shedding, a vaginal delivery can be performed and the newborn is examined and cultured after delivery.

- Some doctors recommend anti-viral medication for pregnant women who are infected with HSV-2. Recent studies indicate that acyclovir (Zovirax, generic) valacyclovir (Valtrex), or famciclovir (Famvir) can help reduce the recurrence of genital herpes and the need for Cesarean sections. Women begin to take the drug on a daily basis beginning in the 36th week of pregnancy.

- Breastfeeding after delivery is safe unless there is a herpes lesion on the breast.

Potential Effects of Herpes in the Newborn

Herpes infection in a newborn can cause a range of symptoms, including skin rash, fevers, mouth sores, and eye infections. If left untreated, neonatal herpes is a very serious and even life-threatening condition. Neonatal herpes can spread to the brain and central nervous system, causing encephalitis and meningitis and can lead to mental retardation, cerebral palsy, and death. Herpes can also spread to internal organs, such as the liver and lungs.

Infants infected with herpes are treated with acyclovir. It is important to treat babies quickly, before the infection spreads to the brain and other organs.

Effects on the Brain and Central Nervous System

Herpes Encephalitis. Each year in the U.S., herpes accounts for about 2,100 cases of encephalitis, a rare but extremely serious brain disease. Untreated, herpes encephalitis is fatal over 70% of the time. Respiratory arrest can occur within the first 24 - 72 hours. Fortunately, rapid diagnostic tests and treatment with acyclovir have significantly improved survival rates and reduced complication rates. Nearly all who recover suffer some impairment, ranging from very mild neurological changes to paralysis. Patients who are treated with acyclovir within 2 days of becoming ill have the best chance for a favorable outcome.

Herpes Meningitis. Herpes meningitis, an inflammation of the membranes that line the brain and spinal cord, occurs in up to 10% of cases of primary genital HSV-2. Women are at higher risk than men for herpes meningitis. Symptoms include headache, fever, stiff neck, vomiting, and sensitivity to light. Fortunately, after lasting for up to a week, herpes meningitis usually resolves without complications, although recurrences have been reported.

Eczema Herpeticum

A form of herpes infection called eczema herpeticum, also known as Kaposi's varicellaform eruption, can affect patients with skin disorders and immunocompromised patients. The disease tends to develop into widespread skin infection that resembles impetigo. Symptoms appear abruptly and can include fever, chills, and malaise. Clusters of dimpled blisters emerge over 7 - 10 days and spread widely. They can become secondarily infected with staphylococcal or streptococcal bacteria. With treatment, lesions heal in 2 - 6 weeks. Untreated, this condition can be extremely serious and possibly fatal.

Ocular Herpes and Vision Loss

Herpetic infections of the eye (ocular herpes) occur in about 50,000 Americans each year. In most cases, ocular herpes causes inflammation and sores on the lids or outside of the cornea that go away in a few days.

Stromal Keratitis. Stromal keratitis occurs in up to 25% of cases of ocular herpes. In this condition, deeper layers of the cornea are involved. Scarring and corneal thinning develop, which may cause the eye's globe to rupture, resulting in blindness. Although rare, it is a major cause of corneal blindness in the US.

Iridocyclitis. Iridocyclitis is another serious complication of ocular herpes, in which the iris and the area around it become inflamed.

Gingivostomatitis

Herpes can cause multiple painful ulcers on the gums and mucous membranes of the mouth, a condition called gingivostomatitis. This condition usually affects children 1 - 5 years of age. It nearly always subsides within 2 weeks. Rarely, it can lead to a viral infection. Children with gingivostomatitis commonly develop herpetic whitlow (herpes of the fingers).

Herpes in Patients with Compromised Immune Systems

Herpes simplex is particularly devastating when it occurs in immunocompromised patients and, unfortunately, co-infection is common. People infected with herpes have an increased risk for contracting HIV. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that all patients diagnosed with HSV-2 should be tested for HIV.

The majority of patients with HIV are co-infected with HSV-2 and are particularly vulnerable to its complications. When a person has both viruses, each virus increases the severity of the other. HSV-2 infection increases HIV levels in the genital tract, which makes it easier for the HIV virus to be spread to sexual partners.

Herpes simplex in any patient with an impaired immune system can cause serious and even life-threatening complications, including:

- Pneumonia

- Inflammation of the esophagus

- Encephalitis (inflammation of the brain)

- Destruction of the adrenal glands

- Disseminated herpes (spread of infection throughout the body)

- Liver damage, including hepatitis

Other Complications

Urinary retention. Urinary retention in women, especially with the first outbreak, is not uncommon. Some women need to use an indwelling catheter for a few days to a week.

Diagnosis

The herpes simplex virus is usually identifiable by its characteristic lesion: A thin-walled blister on an inflamed base of skin. However, other conditions can resemble herpes, and doctors cannot base a herpes diagnosis on visual inspection alone. In addition, many patients who carry the virus do not have visible genital or oral lesions. Laboratory tests are needed to confirm a herpes diagnosis. These tests include:

- Virologic tests (viral culture of the lesion)

- Serologic tests (blood tests that detect antibodies)

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that both virologic and serologic tests be used for diagnosing genital herpes. Patients diagnosed with genital herpes should also be tested for other sexually transmitted diseases.

According to the CDC, up to 50% of first-episode cases of genital herpes are now caused by herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1). However, recurrences of genital herpes, and viral shedding without overt symptoms, are much less frequent with HSV-1 infection than herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2). It is important for doctors to determine whether the genital herpes infection is caused by HSV-1 or HSV-2, as the type of herpes infection influences prognosis and treatment recommendations.

Virologic Tests

Viral culture tests are made by taking a fluid sample, or culture, from the lesions as early as possible, ideally within the first 3 days of the outbreak. The viruses, if present, will reproduce in the culture but may take 1 - 10 days to do so. If infection is severe, testing technology can shorten this period to 24 hours, but speeding up the test may make the results less accurate. Viral cultures are very accurate if lesions are still in the clear blister stage, but they do not work as well for older ulcerated sores, recurrent lesions, or latency. At these stages the virus may not be active enough to reproduce sufficiently to produce a visible culture.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests are much more accurate than viral cultures, and the CDC recommends this test for detecting herpes in spinal fluid when diagnosing herpes encephalitis (see below). PCR can make many copies of the virus’ DNA so that even small amounts of DNA in the sample can be detected. PCR is much more expensive than viral cultures and is not FDA-approved for testing genital specimens. However, because PCR is highly accurate, many labs have used it for herpes testing.

An older type of virologic testing, the Tzanck smear test, uses scrapings from herpes lesions. The scrapings are stained and examined under a microscope for the presence of giant cells with many nuclei or distinctive particles that carry the virus (called inclusion bodies). The test is quick but accurate only 50 - 70% of the time. It cannot distinguish between virus types or between herpes simplex and herpes zoster. The Tzanck test is not reliable for providing a conclusive diagnosis of herpes infection and is not recommended by the CDC.

Serologic Tests

Serologic (blood) tests can identify antibodies that are specific for either herpes virus simplex 1 (HSV-1) or herpes virus simplex 2 (HSV-2). When the herpes virus infects someone, their body’s immune system produces specific antibodies to fight off the infection. If a blood test detects antibodies to herpes, it’s evidence that you have been infected with the virus, even if the virus is in a non-active (dormant) state. The presence of antibodies to herpes also indicates that you are a carrier of the virus and might transmit it to others.

Newer “type-specific” assays test for antibodies to two different proteins that are associated with the herpes virus:

- Glycoprotein gG-1 is associated with HSV-1

- Glycoprotein gG-2 is associated with HSV-2

Although glycoprotein (gG) type-specific tests have been available since 1999, many of the older nontype-specific tests are still on the market. The CDC recommends only type-specific glycoprotein (gG) tests for herpes diagnosis.

Serologic tests are most accurate when performed 12 - 16 weeks after exposure to the virus. Recommended tests include:

- HerpeSelect. This includes two tests: ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) or Immunoblot. Both are highly accurate in detecting both types of herpes simplex virus. Samples need to be sent to a lab, so results take longer than the in-office Biokit test.

- Biokit HSV-2 (also marketed as SureVue HSV-2). This test detects HSV-2 only. Its major advantages are that it requires only a finger prick and results are provided in less than 10 minutes. It is very accurate, although slightly less so than the other tests. It is also less expensive.

- Western Blot Test. This is the gold standard for researchers with accuracy rates of 99%. It is costly and time consuming, however, and is not as widely available as the other tests.

False-negative (testing negative when herpes infection is actually present) results can occur if tests are done in the early stages of infection. False-positive results (testing positive when herpes infection is not actually present) can also occur, although less often than false-negative. Your doctor may recommend that you have the test repeated.

Doctors recommend serologic herpes tests especially for:

- People who have had recurrent genital symptoms but no positive herpes viral cultures

- People who have visible symptoms of genital herpes

- The partner of individuals diagnosed with genital herpes

- People who have multiple sex partners and who need to be tested for different types of STDs

At this time, doctors do not recommend screening for HSV-1 or HSV-2 in the general population.

Tests for Herpes Encephalitis

It may take a number of tests to diagnose herpes encephalitis.

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of cerebrospinal fluid detects tiny amounts of DNA from the virus, and then replicates them millions of times until the virus is detectable. This test can identify specific strains of the virus. PCR identifies HSV in cerebrospinal fluid and gives a rapid diagnosis of herpes encephalitis in most cases, eliminating the need for biopsies. The CDC recommends PCR for diagnosing herpes central nervous system infections.

Imaging Tests. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans may be used to differentiate encephalitis from other conditions.

Brain Biopsy. Brain biopsy is the most reliable method of diagnosing herpes encephalitis, but it is also the most invasive and is generally performed only if the diagnosis is uncertain. With the increased use of PCR, biopsies for herpes are now only rarely performed.

Similar Conditions

Canker Sores (Aphthous Ulcers). Simple canker sores (known medically as aphthous ulcers) are often confused with the cold sores of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1). Canker sores frequently crop up singly or in groups on the inside of the mouth or on or under the tongue. Their cause is unknown, and they are common in perfectly healthy people. They are usually white or grayish crater-like ulcers with a sharp edge and a red rim. They usually heal within 2 weeks without treatment.

Thrush (Candidiasis). Candidiasis is a yeast infection that causes a whitish overgrowth in the mouth. It is most common in infants but can appear in people of all ages, particularly people taking antibiotics or those with impaired immune systems.

Other conditions that may be confused with oral herpes include herpangina (a form of the Coxsackie A virus), sore throat caused by strep or other bacteria, and infectious mononucleosis.

Genital Disorders

Conditions that may be confused with genital herpes include bacterial and yeast infections, genital warts, syphilis, and certain cancers.

Urinary Tract Infections

In rare cases, HSV-2 may occur without lesions and resemble cystitis and urinary tract infections.

Eye Injuries

Simple corneal scratches can cause the same pain as herpetic infection, but these usually resolve within 24 hours and don't exhibit the corneal lesions characteristic of herpes simplex.

Skin Disorders

Skin disorders that may mimic herpes simplex include shingles and chicken pox (both caused by varicella-zoster, another herpes virus), Molluscum contagiosum (a viral skin disease that produces small rounded swellings), scabies, impetigo, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome, a serious inflammatory disease usually caused by a drug allergy.

Treatment for Genital Herpes

No drug can cure herpes simplex virus. The infection may recur after treatment has been stopped and, even during therapy, a patient can still transmit the virus to another person. Drugs can, however, reduce symptoms and improve healing times.

Acyclovir and Related Drugs

Antiviral drugs called nucleosides or nucleotide analogues are the main drugs used to treat genital herpes. They are taken by mouth. (Acyclovir is also available as an ointment, but the oral form is much more effective.) These drugs limit herpes viral replication and its spread to other cells. They are not cures, however.

Three drugs are approved to treat genital herpes:

- Acyclovir (Zovirax or generic)

- Valacyclovir (Valtrex)

- Famciclovir (Famvir)

The drugs are used initially to treat a first attack of herpes, and then afterward to either suppress the virus to prevent recurrences or to treat recurrent outbreaks.

To treat outbreaks, drug regimens depend on whether it is the first episode or a recurrence and on the medication and dosage prescribed. Most medications need to be taken several times a day. For a first episode, treatment usually lasts 7 - 10 days. For a recurrent episode, treatment takes 1 - 5 days depending on the type of medication and dosage.

To suppress outbreaks, treatment requires taking pills daily on a long-term basis. Acyclovir and famciclovir are taken twice a day, valacyclovir once a day.

Suppressive treatment can reduce outbreaks by 70 - 80%. It is generally recommended for patients who have frequent recurrences (6 or more outbreaks per year). Valacyclovir may work especially well for preventing herpes transmission among heterosexual patients when one partner has herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2) and the other partner does not. However, valacyclovir may not be as effective as acyclovir for patients who have very frequent recurrences of herpes (more than 10 outbreaks per year). According to the most recent guidelines from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, famciclovir is somewhat less effective than acyclovir or valacyclovir for suppressing viral shedding.

Because the frequency of herpes recurrences often diminishes over time, patients should discuss annually with their doctors whether they should stay with drug therapy or discontinue it. Studies suggest that daily drug therapy is safe and effective for up to 6 years with acyclovir, and up to 1 year with valacyclovir or famciclovir.

Side Effects. Nausea and headache are the most common side effects, but in general these drugs are safe. Although there is some evidence these drugs may reduce shedding, they probably do not prevent it entirely. The use of condoms during asymptomatic periods is still essential, even when patients are taking these medications.

Risk for Resistant Viruses. As with antibiotics, doctors are concerned about signs of increasing viral resistance to acyclovir and similar drugs, particularly in immunocompromised patients (such as those with HIV/AIDS). Most patients on long-term suppressive drug therapy show few signs of drug resistance. However, patients who do not respond to standard regimens should be monitored for emergence of drug resistance.

Treatment for Oral Herpes

Oral Treatments

Acyclovir (Zovirax, generic), valacyclovir (Valtrex), and famciclovir (Famvir) -- the anti-viral pills used to treat genital herpes -- can also treat the cold sores associated with oral herpes. In addition, acyclovir is available in topical form, as is penciclovir (a related drug).

Topical Treatments

These ointments or creams can help shorten healing time and duration of symptoms. However, none are truly effective in eliminating outbreaks.

- Penciclovir (Denavir) heals herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) sores on average about half a day faster than without treatment, stops viral shedding, and reduces the duration of pain. Ideally, the patient should apply the cream within the first hour of symptoms, although the medication can still help if applied later. The drug is continued for 4 consecutive days, and should be reapplied every 2 hours while awake.

- Acyclovir cream (Zovirax, generic) works best when applied early (at the first sign of pain or tingling).

- Docosanol cream (Abreva) is the only FDA-approved non-prescription ointment for oral herpes. The patient applies the cream five times a day, beginning at the first sign of tingling or pain. Studies have been mixed on the cream’s benefits.

- Over-the-counter topical ointments may provide modest relief. They include Anbesol gel, Blistex lip ointment, Camphophenique, Herpecin-L, Viractin, and Zilactin. Some contain a topical anesthetic such as benzocaine, tetracaine, or phenol.

Home Remedies

Patients can manage most herpes simplex infections that develop on the skin at home with over-the-counter painkillers and measures to relieve symptoms.

Symptomatic Relief

Several simple steps can produce some relief:

- Hygiene is important. Avoid touching the sores. Wash hands frequently during the day. Fingernails should be scrubbed daily. Keep the body clean.

- Drink plenty of water.

- Keep blisters or sores clean and dry with cornstarch or similar product. (Women should avoid using talcum powder in genital areas; some studies suggest that talcum powder may increase the risk for ovarian cancer.)

- Some people report that drying the genital area with a blow dryer on the cool setting offers relief.

- Avoid tight-fitting clothing, which restricts air circulation and slows healing of the sores.

- Choose cotton underwear, rather than synthetic materials.

- Local application of ice packs may alleviate the pain and help reduce recurrences.

- Lukewarm baths may be helpful.

- Wearing sun block helps prevent sun-triggered recurrence of herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1).

- Avoid sex during both outbreaks and prodromes (the early symptoms of herpes), when signs include tingling, itching, or tenderness in the infected areas.

- Use over-the-counter medications, such as aspirin, acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic), or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin, generic), to reduce fever and local tenderness.

Herbs and Supplements

Generally, manufacturers of herbal remedies and dietary supplements do not need FDA approval to sell their products. Just like a drug, herbs and supplements can affect the body's chemistry, and therefore have the potential to produce side effects that may be harmful. There have been several reported cases of serious and even lethal side effects from herbal products. Always check with your doctor before using any herbal remedies or dietary supplements.

Many herbal and dietary supplement products claim to help fight herpes infection by boosting the immune system. There has been little research on these products, and little evidence to show that they really work. Some are capsules taken by mouth. Others come in the form of ointment that is applied to the skin. Popular herbal and supplement remedies for herpes simplex include:

- Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea)

- Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus)

- Aloe (Aloe vera)

- Bee products that contain propolis, a tree resin collected by bees

- Lysine

- Zinc

The following are special concerns for people taking natural remedies for herpes simplex:

- Echinacea can lower white blood cell levels when taken for long periods of time. This herb can also interfere with drugs that are used to treat immune system disorders.

- Siberian ginseng can raise blood pressure levels.

- Bee products (like propolis) can cause allergic reactions in people who are allergic to bee stings.

- Lysine should not be taken with certain types of antibiotics.

- Taking zinc in large amounts (more than 200 mg/day) can cause stomach upset and an impaired sense of smell.

Resources

- www.ashastd.org -- American Social Health Association

- www.niaid.nih.gov -- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- www.cdc.gov/std/herpes -- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

References

Berger JR, Houff S. Neurological complications of herpes simplex virus type 2 infection. Arch Neurol. May 2008; 65(5):596-600.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Seroprevalence of herpes simplex virus type 2 among persons aged 14 - 49 years -- United States, 2005-2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Apr 23;59(15):456-9.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 Dec 17;59(RR-12):1-110.

Cernik C, Gallina K, Brodell RT. The treatment of herpes simplex infections: An evidence-based review. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jun 9;168(11):1137-1144.

Corey L, Wald A. Maternal and neonatal herpes simplex virus infections. N Engl J Med. 2009 Oct 1;361(14):1376-85.

Fatahzadeh M, Schwartz RA. Human herpes simplex virus infections: epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Nov;57(5):737-63.

Gardella C, Brown Z. Prevention of neonatal herpes. BJOG. 2011 Jan;118(2):187-92. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02785.x.

Gupta R, Warren T, Wald A. Genital herpes. Lancet. 2007;370:2127-2137.

Hollier LM, Wendel GD. Third trimester antiviral prophylaxis for preventing maternal genital herpes simplex virus (HSV) recurrences and neonatal infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Jan 23;(1):CD004946.

Lebrun-Vignes B, Bouzamondo A, Dupuy A, Guillaume JC, Lechat P, Chosidow O. A meta-analysis to assess the efficacy of oral antiviral treatment to prevent genital herpes outbreaks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Aug;57(2):238-46. Epub 2007 Apr 9.

Martin ET, Krantz E, Gottlieb SL, Magaret AS, Langenberg A, Stanberry L, et al. A pooled analysis of the effect of condoms in preventing HSV-2 acquisition. Arch Intern Med. 2009 Jul 13;169(13):1233-40.

Tobian AA, Serwadda D, Quinn TC, Kigozi G, Gravitt PE, Laeyendecker O, et al. Male circumcision for the prevention of HSV-2 and HPV infections and syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 26;360(13):1298-309.

Tronstein E, Johnston C, Huang ML, Selke S, Magaret A, Warren T, et al. Genital shedding of herpes simplex virus among symptomatic and asymptomatic persons with HSV-2 infection. JAMA. 2011 Apr 13;305(14):1441-9.

Xu F, Sternberg MR, Kottiri BJ, McQuillan GM, Lee FK, Nahmias AJ, et al. Trends in herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2 seroprevalence in the United States. JAMA. 2006 Aug 23;296(8):964-73.

|

Review Date:

12/19/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |