Birth control options for women

Highlights

Birth Control Options

Birth control options for women include:

- Hormonal contraceptives, such as birth control pills, skin patch, vaginal ring, injection, implant

- Intrauterine devices (IUDs), which contain either a hormone or copper

- Barrier devices, such as condoms, diaphragm, cervical cap, sponge

- Fertility awareness methods

- Sterilization

The condom is the only form of birth control that protects against sexually transmitted diseases.

Drospirenone and Blood Clots

In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) completed its safety review of drospirenone-containing birth control pills and concluded that drospirenone has a much higher risk for causing blood clots than levonorgestrel or other types of progestin. Drospirenone is the progestin used in the Yaz and Beyaz brand birth control pills.

IUDs and Implants for Adolescents

In 2012, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended that intrauterine devices (IUDs) and contraceptive implants (Implanon, Nexplaon) be offered as first-line contraceptive options for sexually active teens. ACOG based its recommendation on the effectiveness of these contraceptives and high rates of patient satisfaction.

A 2012 New England Journal of Medicine study found that long-acting contraceptives such as IUDs and implants are 20 times more effective at preventing pregnancy than short-acting birth control pills, patches, or rings.

Drug Approval

In 2012, the FDA approved the birth control pill Natazia as a treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding. Oral contraceptives (OCs) are often prescribed to help with menstrual disorders but this is the first OC approved specifically for this purpose. Natazia is a combination OC that contains the estrogen estradiol and the progesterone dienogest.

.

Introduction

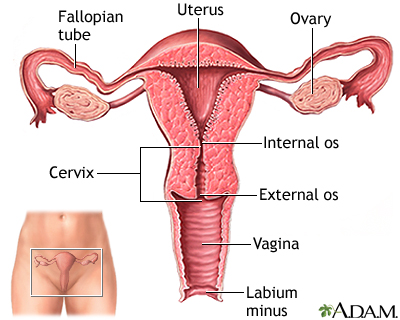

Contraceptives are devices, drugs, or methods for preventing pregnancy either by preventing the fertilization of the female egg by the male sperm or by preventing implantation of the fertilized egg.

Contraceptive Options

Choosing the appropriate contraceptive is a personal decision. Contraceptive options include:

- Hormonal contraceptives (such as oral contraceptives, skin patch, vaginal ring, implant, and injection)

- Intrauterine devices (IUDs), which contain either a hormone or copper

- Barrier devices with or without spermicides (such as diaphragm, cervical cap, sponge, and condom)

- Fertility awareness methods (such as temperature, cervical mucus, calendar, and symptothermal)

- Female sterilization (tubal ligation, Essure)

- Vasectomy [For more information, see In-Depth Report #37: Vasectomy and vasectomy reversal.]

The condom is the only birth control method that provides protection against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).

Determining Effectiveness

Contraceptive effectiveness is characterized by "typical use" and "perfect use":

- Typical use refers to real-life conditions, in which mistakes (such as forgetting to take a birth control pill at the right time) sometimes happen.

- Perfect use refers to contraceptives that are used correctly each time intercourse occurs.

The most effective standard female contraceptives have a failure rate of less than 1% with typical (normal) use. They are:

- Intauterine devices (IUDs)

- Implants

- Surgical sterilization

By comparison, failure rates for the male latex condom are about 18% with typical use and 2% with perfect use. Failure rates for hormonal contraception are about 9% for the first year of typical use. To put these rates into perspective, a sexually active woman of reproductive age who does not use contraception faces an 85% likelihood of becoming pregnant in the course of a year.

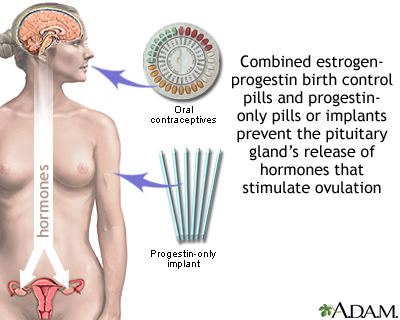

Oral Contraceptives and Combination Hormonal Methods

Oral contraceptives (OCs, birth control pills, or “the Pill,”) are available by prescription and come in either a combination of estrogen and progestin or progestin alone. Most women use the combination hormone pill. Women who experience severe headaches or high blood pressure from the estrogen in the combined pill can take the progestin-only pill.

The birth control pill is the most popular form of contraception in the United States, used by more than 10 million American women.

Birth control pills work by:

- Preventing ovulation. Ovulation is the release of the egg from an ovary. If no egg is released, fertilization by sperm cannot occur.

- Preventing entry of sperm into the uterus by keeping the cervical mucus thick and sticky.

When a woman stops taking the pill, she usually regains fertility within 3 - 6 months.

Hormones Used in Birth Control Pills

Most birth control pills contain a combination of an estrogen and a progesterone (in a synthetic form called progestin). The estrogen compound used in most combination OCs is estradiol. There are many different progestins, but common types include levonorgestrol, drospirenone, norgestrol, norethindrone, and desogestrel.

These hormones can cause temporary side effects especially during the first 2 - 3 months of birth control use. Common side effects of oral contraceptives include:

- Breakthrough bleeding during the first few months

- Nausea and vomiting (can often be controlled by taking the pill during a meal or at bedtime)

- Headaches (in women with a history of migraines, they may worsen)

- Breast tenderness and enlargement

- Irregular bleeding or bleeding between periods

Although women are often concerned about weight gain, most studies have not found this to be a side effect associated with oral contraceptives. The estrogen in combination birth control pills may cause some fluid retention.

Dosing and Pill Packs

Women who take birth control pills need to be sure to take the pills every day. It’s best to get in the habit of taking the pill at the same time every day. Your risk for becoming pregnant if you miss a dose depends on the type of pill you are taking. Progestin-only pills have a stricter schedule than combination hormone pills.

For 28-day or 21-day combination OCs, catch-up doses depend on when in the cycle you forgot to take the pill. Read the directions that come with your pills and check with your doctor or pharmacist if you have any questions. It is a good idea to keep on hand a back-up form of barrier birth control (condom, spermicide, sponge). Emergency (“morning after”) contraception is another option.

Standard OCs. Traditional combination birth control pills come in either a:

- 28-pill pack with 21 days of “active” (hormone) pills and 7 days of “inactive” (placebo) pills.

- 21-pill pack with 21 days of “active” pills. You wait 7 days and then begin a new pack.

Continuous-Dosing OCs. Extended-cycle (also called “continuous-use” or “continuous-dosing”) oral contraceptives aim to reduce -- or even eliminate -- monthly menstrual periods. These OCs contain a combination of estradiol and the progestin levonorgestrel, but they use extending dosing of active pills.

- Seasonale uses 81 days of active pills followed by 7 days of inactive pills. Women who take Seasonale have on average a period every 3 months.

- Seasonique uses 84 days of levonorgestrol-estradiol pills followed by 7 days of pills that contain only low-dose estradiol. It also produces a period about 3 – 4 times a year.

- Lybrel contains only active pills, which are taken 365 days a year. The pills supply a daily low dose of levonorgestrol and estradiol. Lybrol completely eliminates monthly menstrual periods for many women and significantly reduces in bleeding in most others.

Progestin-Only Pills. Progestin-only pills come in 28-pill pack that contains all active pills. Progestin-only pills, also called “mini-pills,” must be taken at precisely the same time each day. You can become pregnant if you delay taking a pill by even 3 hours.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Birth Control Pills

Oral contraceptives are the choice of most American women who use birth control, making them the most popular reversible contraceptives in the U.S. Oral contraceptives are among the most effective contraceptives. With perfect use (taking the pill every day), fewer than 1 in 100 women become pregnant each year while on birth control pills. With typical use (sometimes missing a dose), about 9 in 100 women become pregnant.

Advantages and Benefits of OCs. In addition to preventing pregnancy, oral contraceptives may also have the following advantages:

- Control heavy menstrual bleeding and cramping, which are often symptoms of uterine fibroids and endometriosis (Natazia is approved for controlling heavy bleeding)

- Prevent iron deficiency anemia caused by heavy bleeding

- Reduce pelvic pain caused by endometriosis

- Protect against ovarian and endometrial cancer with long-term use (more than 3 years)

- Reduce symptoms of premenstrual dysphoric disorder (the Yaz and Beyaz brands are approved for treating PMDD)

- Improve acne (Yaz, Estrostep, and Ortho Tri-Cyclen are approved specifically for this)

Disadvantages and Serious Risks of OCs. Combination birth control pills can increase the risk of developing or worsening certain serious medical conditions. The risks depend in part on a woman’s medical history. Deep vein thrombosis, heart attack, and stroke are some of the major risks associated with combination birth control pills.

Birth control pills are not recommended for women who:

- Are over age 35 and smoke

- Have uncontrolled high blood pressure, diabetes, or polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

- Have a history of heart disease, stroke, or blood clots or heart disease risk factors (unhealthy cholesterol levels, obesity)

- Have migraine with aura

Serious risks of birth control pills may include:

- Venous Thromboembolism (VTE). All combination estrogen/progestin birth control products carry an increased risk for blood clots in the veins (venous thromboembolism), which can lead to blood clots in the arteries of the leg (deep vein thrombosis) or lungs (pulmonary embolism). The FDA warns that birth control pills that contain drospirenone (found in Yaz and Beyaz) may increase the risk for blood clots much more than other types of birth control pills.The Centers for Disease Control recommends that due to the risks of VTE, women should not use combined hormonal contraceptives for 21 - 42 days after giving birth.

- Heart and Circulation Problems. Combination birth control pills contain estrogen, which can increase the risk for stroke, heart attack, and blood clots in some women

- Cancer Risks. Several studies have reported an association between increased risk of cervical cancer and long-term (greater than 5 years) use of oral contraception. Recent research indicates that OCs do not significantly increase breast cancer risk.

- Liver Problems. In rare cases, oral contraceptives have been associated with liver tumors, gallstones, or jaundice. Women with a history of liver disease, such as hepatitis, should consider other contraceptive options.

- Interactions with Other Medications. Certain types of medications can interact with and decrease the effectiveness of OCs. These medications include anticonvulsants, antibiotics, antifungals, and antiretrovirals. The herbal remedy St. John’s wort can interfere with birth control pills’ effectiveness. Make sure your doctor is aware of any drugs, vitamins, or herbal supplements that you take

- HIV and STDs. Birth control pills do not protect against any sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), including HIV. Unless they have a monogamous relationship with an uninfected partner, all women should be sure a condom is being used during sexual intercourse, regardless of whether or not they take oral contraceptives

Other Combination Hormonal Contraceptives (Patch and Ring)

The skin patch and vaginal ring are other hormonal contraceptive methods of administering the combination of progestin and estrogen.

Skin Patch. Ortho Evra is a birth control skin patch. It contains a progestin (norelgestromin) and estrogen. The patch is placed on the lower abdomen, buttocks, or upper body (but not on the breasts). Each patch is worn continuously for a week and reapplied on the same day of each week. After three weekly patches, the fourth week is patch-free, which allows menstruation. (The patch remains effective for 9 days, so being slightly late in changing it should not increase the risk for pregnancy.)

The Ortho patch exposes women to higher levels of estrogen than most birth control pills, and therefore increases the risk for blood clots in the veins (venous thromboembolism). Venous thromboembolism can cause blockage in lung arteries and other serious side effects. Older women (over age 40) and women with risk factors for blood clots (such as cigarette smoking or a family history of blood clots) may find other birth control products to be a safer choice. Discuss with your doctor whether the patch is appropriate for you.

Vaginal Ring. NuvaRing is a 2-inch flexible ring that contains both estrogen and progestin (etonogestrel). It is inserted into the vagina. Women can insert the ring by themselves once a month and take it out at the end of the third week to allow menstruation. It works well and may cause less irregular bleeding than oral contraceptives. Some women find it uncomfortable, and a few have reported vaginal irritation and discharge, but such problems rarely cause a woman to discontinue use. As with the patch, NuvaRing may put women who use it at higher risk for blood clots than oral contraceptives.

Implant Contraceptives

Implant contraception involves inserting a rod under the skin. The rod releases tiny amounts of the hormone progestin into the bloodstream.

The first implant was the Norplant system, which used six rods that contained levonorgestrel. Due in part to serious complications, Norplant was withdrawn from the U.S. market in 2002. The main complication was difficulty inserting and, in particular, removing the rods. (Many women experienced scarring.) In addition, some women who used Norplant experienced heavy irregular bleeding. A two-rod implant called Jadelle is sold in other countries, but not the United States.

In 2006, the FDA approved Implanon, a new implant contraceptive. A new version of Implanon, called Nexplanon, was approved in 2011. In contrast to Norplant:

- Implanon/Nexplanon uses one rod, not six.

- It is not inserted as deeply into the skin.

- It uses etonogestrel, a different type of progestin than the levonorgestrel used in Norplant.

- Only specially trained health care providers are allowed to insert and remove Implanon.

Implant insertion takes about a minute and is performed with a local anesthetic in a doctor’s office. The rod remains in place for 3 years, although it can be removed at any time. (The removal procedure takes a few minutes longer than insertion.) After the rod is removed, a new one can be inserted.

Implant contraception is very effective with failure rates of less than 1%. It is 20 times more effective than short-acting contraceptives like birth control pills. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends implant contraception or intrauterine devices (IUDs) as first-line contraceptive options for adolescents.

Studies indicate that Implanon/Nexplanon is safe. Irregular bleeding and headaches are the main side effects. Although the risk for pregnancy is very low (fewer than 1 of 100 women), if conception does occur there is an increased risk for ectopic pregnancy, which is a dangerous condition. Implants can also increase the risks for ovarian cysts, and for blood clots.

Injected Contraceptives

Injected contraceptives are given once every 3 months. Most injectables are progestin-only. In the United States, depo-medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera) is the only approved injected contraceptive. Depo-Provera (also called Depo, or DMPA) uses a progestin called medroxyprogesterone.

Depo-Provera is very effective in preventing pregnancies. About 3 in 100 women who use it become pregnant. However, Depo also carries the risk for many mild and serious side effects including the loss of bone density (see "Disadvantages"). Because of this complication, Depo-Provera should not be used for longer than 2 years.

Administering Injections:

- A physical examination is necessary before beginning the injections.

- Depo is injected into a muscle in the patient's arm or buttock. During months between injections, the hormone slowly diffuses out of the muscle into the bloodstream.

- Depo requires an injection by the doctor once every 3 months.

- If more than 2 weeks pass beyond the regular injection schedules, the woman should have a pregnancy test before receiving the next injection.

Candidacy

Because Depo-Provera does not contain estrogen, it is safe for many women who may be riskier candidates for combination oral contraceptive use, such as women over age 35, women with high blood pressure, obese women, and smokers.

Depo-Provera should not be given to women who have a history of:

- Current or past breast cancer

- Stroke or blood clots

- Liver disease

- Epilepsy, migraine, asthma, heart failure, or kidney disease (due to the fact that the drug causes fluid retention)

- Unexplained vaginal bleeding

- Risk for osteoporosis

Because of the long lag time between ending treatments and restoration of fertility, Depo-Provera is not recommended for women who are thinking of becoming pregnant within 2 years.

Advantages of Depo-Provera

- Provides highly effective reversible protection against pregnancy without placing heavy demands on the user's time or memory.

- Does not increase risk for breast, ovarian, or cervical cancer. May protect against endometrial cancer.

- May be useful for women with painful periods, heavy bleeding (including heavy bleeding caused by fibroids), premenstrual syndrome, and endometriosis.

Disadvantages and Complications of Depo-Provera

- Weight gain. Most women gain an average of 5 - 8 pounds.

- Other common side effects include menstrual irregularities (bleeding or cessation of periods), abdominal pain and discomfort, dizziness, headache, fatigue, nervousness.

- Most users of Depo-Provera stop menstruating altogether after a year. Depo can cause persistent infertility for up to 22 months after the last injection, although the average is 10 months.

- Long-term (more than 2 years) use of Depo-Provera can cause loss of bone density. Depo-Provera’s label warns that the decline in bone density increases with duration of use and may not be completely reversible even after the drug is discontinued. The FDA recommends that Depo-Provera should not be used for longer than 2 years unless other birth control methods are inadequate. Some studies indicate that this bone loss may be reversible once Depo-Provera use is discontinued. Some doctors recommend that women take calcium and vitamin D supplements while on Depo-Provera.

- The injections do not provide protection against sexually transmitted diseases including HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. Some research suggests that the progestin in injected contraceptives may cause changes in the vagina or cervix that increase susceptibility to HIV. This effect has not been proven, but in any case women who use Depo-Provera should be sure a condom is in use during sexual intercourse.

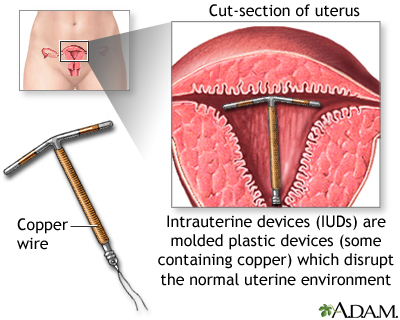

Intrauterine Devices (IUDs)

The intrauterine device (IUD) is a small plastic T-shaped device that is inserted into the uterus. An IUD's contraceptive action begins as soon as the device is placed in the uterus and stops as soon as it is removed. IUDs have an effectiveness rate of close to 100%. They are also a reversible form of contraception. Once the device is removed, a woman regains her fertility.

Intrauterine Device Forms

Two types of intrauterine devices (IUDs) are available in the United States:

- Copper-Releasing (ParaGard). This type of IUD can remain in the uterus for up to 10 years. Copper ions released by the IUD are toxic to sperm, thus preventing fertilization. The copper-releasing IUD is also effective for emergency contraception. (See Emergency Contraception section of this report.)

- Progestin-Releasing (Mirena). This type of IUD can remain in the uterus for up to 5 years. Mirena is also known as a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, or LNG-IUS. The LNG-IUS is long-acting, safe, and very effective in preventing heavy bleeding, and helps reduce cramps. In fact, some doctors describe it as a nearly ideal contraceptive. In addition to being a contraceptive, it is approved as a treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding.

Inserting an Intrauterine Device

With some exceptions, an intrauterine device (IUD) can be inserted at any time, except during pregnancy or when an infection is present. It may be inserted immediately after a woman gives birth or after elective or spontaneous miscarriage. It is typically inserted in the following manner by a trained health professional:

- A plastic tube containing the IUD (the inserter) is slid through the cervical canal into the uterus.

- A plunger in the tube pushes the IUD into the uterus.

- Attached to the base of the IUD are two thin but strong plastic strings. After the instruments are removed, the health care provider cuts the strings so that about an inch of each dangles outside the cervix within the vagina.

The strings have two purposes:

- They enable the user or health care provider to check that the IUD is properly positioned. (Because the IUD has a higher rate of expulsion during menstruation, the woman should also check for the strings after each period, especially if she has heavy cramps.)

- They are used for pulling the IUD out of the uterus when removal is warranted.

The insertion procedure can be painful and sometimes causes cramps, but for many women it is painless or only slightly uncomfortable. Patients are often advised to take an over-the-counter painkiller ahead of time. They can also ask for a local anesthetic to be applied to the cervix if they are sensitive to pain in that area. Occasionally a woman will feel dizzy or light-headed during insertion. Some women may have cramps and backaches for 1 - 2 days after insertion, and others may suffer cramps and backaches for weeks or months. Over-the-counter painkillers can usually moderate this discomfort.

Candidates for the Intrauterine Device

Intrauterine devices are an excellent choice of contraception for women who are seeking a long-term and effective birth control method, particularly those wishing to avoid risks and side effects of contraceptive hormones. The LNG-IUS may be better suited for women with heavy or regular menstrual flow.

Around the time of insertion and shortly afterwards, women should be considered at low risk for sexually transmitted disease (mutually monogamous relationship, using condoms, or not currently sexually active).

Women with risk factors that preclude hormonal contraceptives should probably avoid progestin-releasing IUDs, although the progestin doses are much lower with LNG-IUS and probably do not pose the same risks.

Women with the following history or conditions may be poor candidates for IUDs:

- Current or recent history of pelvic infection (the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease is higher for all women who have multiple sex partners or who are in non-monogamous relationships -- not just those with IUDs)

- Current pregnancy

- Abnormal Pap tests

- Cervical or uterine cancer

- A very large or very small uterus

IUDs have the following advantages:

- The IUD is more effective than oral contraceptives at preventing pregnancy, and it is reversible. Once it is removed, fertility returns. (Studies have found no adverse effects on fertility with the current IUDs.)

- Unlike the pill, there is no daily routine to follow.

- Unlike the barrier methods (spermicides, diaphragm, cervical cap, and the male or female condom), there is no insertion procedure to cope with before or during sex.

- Intercourse can resume at any time, and, as long as the IUD is properly positioned, neither the user nor her partner typically feels the IUD or its strings during sexual activity.

- It is the least expensive form of contraception over the long term.

- IUDs and implant contraceptives are recommended as first-line contraceptive options for adolescents.

Additional advantages, depending on the specific IUD, include:

- The progestin-releasing LNG-IUS (Mirena) is now considered to be one of the best options for treating menorrhagia (heavy menstrual bleeding). (However, irregular breakthrough bleeding can occur during the first 6 months.)

- The copper-releasing IUDs do not have hormonal side effects and may help protect against endometrial (uterine) cancer.

- Both types of IUDs may lower the risk of developing cervical cancer.

Complications of Intrauterine Devices

Menstrual Bleeding. Both types of IUDs affect menstruation:

- Copper-releasing IUDs can cause cramps, longer and heavier menstrual periods, and spotting between periods.

- Progestin-releasing IUDs produce irregular bleeding and spotting during the first few months. Bleeding may disappear altogether. (This characteristic is a major advantage for women who suffer from heavy menstrual bleeding but may be perceived as a problem for others.)

Expulsion. About 2 - 8% of IUDs are expelled from the uterus within the first year. Expulsion is most likely to occur:

- During the first 3 months after insertion.

- During menstruation (women should be sure to check the strings to make sure the IUD is in place)

- If the IUD is inserted immediately after childbirth

- In very rare cases, perforation (puncture) of the uterus can occur during insertion.

Other Safety Concerns. Studies indicate that:

- IUDs may increase the risk for ectopic pregnancy, but women who use IUDs have a very low risk for getting pregnant.

- The LNG-IUS may increase the risk for benign ovarian cysts, but such cysts usually do not cause symptoms and they usually resolve on their own.

- IUDs do not appear to increase the risk for pelvic infection.

- IUDs do not affect fertility or increase the risk for infertility. Once an IUD is removed, fertility is restored.

Spermicidal and Barrier Contraceptives

Barrier contraceptives provide a physical or chemical barrier to block sperm from passing through the cervix into the uterus and fertilizing the egg. Examples of barrier contraceptives include:

- Spermicides

- Condoms, which are the only type of contraception that protects against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs)

- Diaphragms and cervical caps

- Sponge

Spermicides

Spermicides are sperm-killing substances available as foams, creams, gels, films, or suppositories. They are typically used along with another barrier device. Diaphragms and cervical caps require the application of a spermicide to be effective. The sponge comes pre-applied with a spermicide. Some condoms come pre-lubricated with spermicide.

When used alone, the spermicide is inserted into the vagina within 30 minutes of sexual intercourse and must be reapplied every time you have sex.

Spermicides are relatively inexpensive and can be purchased at a drugstore without a prescription. In general, spermicides may be an appropriate choice for women who have intercourse only once in a while, or need backup protection against pregnancy (for instance, if they forget to take their birth control pills). They are not recommended as a primary form of birth control.

Spermicides have several drawbacks:

- Nonoxynol-9, the chemical in U.S.-made spermicides, does not provide any protection against sexually-transmitted diseases. In fact, frequent use of nonoxynol-9 can cause vaginal and rectal irritation and abrasions that may increase the risk for HIV transmission in women.

- Use of a spermicide with a barrier device may increase the risk for a urinary tract infection in women.

- Condoms that come pre-lubricated with spermicide are not recommended. Research indicates that the spermicide does not make them any more effective than condoms without spermicide. Spermicidal lubricated condoms expire faster than those without spermicide. Non-spermicidal lubricated condoms are safe to use and are a better choice.

Condoms

The condom is the only type of birth control that protects against sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) including HIV, the virus that causes AIDS.

Male Condom. The male condom is a thin sheath that is rolled onto an erect penis. If used perfectly each time, the annual risk for pregnancy is about 2%. With typical use, the average annual rate of pregnancy is about 17%.

Male condoms are available in different materials:

- Latex (rubber)

- Polyurethane (plastic)

- Animal membrane (usually lambskin)

Latex condoms are the most common. They are less likely to slip or break than those made of polyurethane. Polyurethane condoms are recommended for people who are allergic to latex or who find the smell of latex unpleaseant. Condoms made from animal membrane (such as lambskin) can prevent pregnancy, but they are permeable and do not protect against sexually transmitted infections.

Most condoms come pre-lubricated. Lubricants can also be purchased and applied separately.

- Only water-based lubricants (K-Y Jelly, Astroglide, AquaLube, glycerin) should be used with latex condoms.

- Do not use petroleum jelly or other oil-based lubricant products as they can damage the condom.

- In general, it's best to use a pre-lubricated condom or to apply a water-based lubricant. Unlubricated condoms may injure vaginal tissue and make it vulnerable to infections. Unlubricated condoms are also more likely to break.

Female Condom. The female condom is a thin 7 inch lubricated pouch made of polyurethane. It comes with a ring at both ends:

- The ring at the closed end is used to insert the device into the vagina and hold it in place over the cervix.

- The ring at the open end remains outside the vagina and partly covers the labia (lips).

The female condom offers effective protection against pregnancy and STDs. It can be inserted up to 8 hours before sex, but is visible outside of the vagina. Some women have difficulty with the insertion. Female condoms are more expensive than male condoms and (like male condoms) can only be used once.

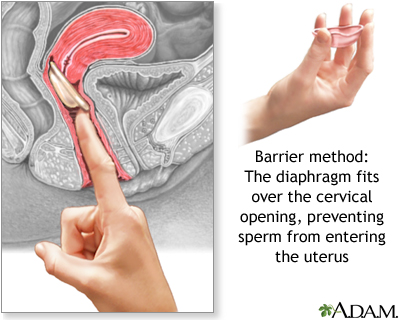

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a small dome-shaped latex cup with a flexible ring that fits over the cervix. The cup acts as a physical barrier against the entry of sperm into the uterus. A diaphragm is usually used along with a spermicide, although whether spermicide is necessary is an issue of some debate.

Diaphragms come in different sizes and require a fitting by a trained health care provider. Some women will need to be refitted with a different-sized diaphragm after pregnancy, abdominal or pelvic surgery, or weight loss or gain of 10 pounds or more. As a general rule, diaphragms should be replaced every 1 - 2 years.

Using and Inserting the Diaphragm. The diaphragm can be placed in the vagina up to 1 hour before intercourse. The following are general guidelines for insertion:

- Before or after each use, the woman should hold the diaphragm up to the light and fill it with water to check for holes, tears, or leaks.

- A small amount of spermicide (about 1 tablespoon) is usually placed inside the cup, and some is smeared around the lip of the cup.

- The device is then folded in half and inserted into the vagina by hand or with the assistance of a plastic inserter.

- The diaphragm should fit over the cervix, blocking entry to the womb.

- If more than 6 hours pass before repeat intercourse occurs, the diaphragm is left in place and extra spermicide is inserted into the vagina using an applicator.

- The diaphragm must remain in the vagina for 6 - 8 hours after the final act of intercourse, and can safely stay there up to 24 hours after insertion. It should not stay in place for more than 24 hours and should not be used during menstrual periods.

- The diaphragm should be washed with soap and warm water after each use and then dried and stored in its original container, which should be kept in a cool dry place.

Advantages of the Diaphragm. The diaphragm can be carried in a purse, can be inserted up to an hour before intercourse begins, and usually (although not always) cannot be felt by either partner. It does not interfere with a woman’s hormones.

Disadvantages and Complications of the Diaphragm. Some disadvantages or complications are as follows:

- Failure rates are high, about 16% with typical use.

- The diaphragm can be dislodged during sex.

- Frequent urinary tract infections and vaginal infections are a problem for some women. Be sure to urinate before inserting the device and after intercourse.

- Women who have a history of recurrent urinary tract infections, toxic shock syndrome, or allergies to latex should not use the diaphragm.

- The diaphragm does not protect against sexually transmitted diseases.

Cervical Cap

The cervical cap (FemCap) is a thimble-shaped latex cup that fits over the cervix. It is always used with a spermicidal cream or gel. It is similar to a diaphragm, but smaller, and is available in only four sizes. The cap is sold by prescription and requires a pelvic examination, Pap test, and fitting by a health care provider.

Insertion and Use of the Cervical Cap. After a small amount of spermicide is placed in the cap, the device is inserted by hand. As in diaphragm use, instruction and practice is required. The cap must be kept in the vagina for 8 hours after the final act of intercourse. Caps wear out and should be replaced every 1 - 2 years. A refitting may also be needed when a woman experiences certain changes in her health or physical status.

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Cervical Cap. The cervical cap is similar to the diaphragm in terms of most advantages and disadvantages. Unlike the diaphragm, the cervical cap can safely remain in the vagina for up to 48 hours (twice the time limit for a diaphragm).

The Sponge

The sponge is a disposable form of barrier contraception. It is made of soft polyurethane foam coated with spermicide, is round in shape, and fits over the cervix like a diaphragm, but is smaller and easily portable. The Today sponge is the only brand of contraceptive sponge available in the United States.

Use and Insertion. To use the sponge, the woman first wets it with water, then inserts it into the vagina with a finger, using a nylon cord loop attachment. It can be inserted up to 6 hours before intercourse and should be left in place for at least 6 hours following intercourse. The sponge provides protection for up to 12 hours. It should not be left in for more than 30 hours from time of insertion.

The sponge should not be used during menstruation, after childbirth, miscarriage, or termination of pregnancy, or by women with a history of toxic shock syndrome.

Advantages and Disadvantages. The sponge is easy to use, is not felt during intercourse, and can be inserted up to 6 hours before intercourse. However, because it contains the spermicide nonoxynol-9, it does not protect against sexually transmitted diseases and may increase the risk for vaginal irritation and transmission of HIV. [See Spermicides section.]

Fertility Awareness Methods

Fertility awareness methods, also called natural family planning, are cycle-based methods that rely on tracking the changes in the body that signal fertility. A woman is only fertile during part of her menstrual cycle. By monitoring certain changes in her body, a woman can more or less predict the fertile phase and abstain from sexual intercourse during that time. She can also use barrier methods if they are not prohibited by religious beliefs.

Fertility awareness methods include:

- Temperature

- Cervical mucus (ovulation)

- Calendar

- Symptothermal

Temperature Method. To determine the most likely time of ovulation and therefore the time of fertility, a woman is instructed to take her body temperature, called her basal body temperature. This is the body's temperature as it rises and falls in accord with hormonal fluctuations.

- Each morning before rising, take your temperature with a special basal body thermometer and mark the result on a graph-paper chart.

- Note the days of menstruation and sexual activity.

- The so-called "fertile window" is 6 days long. It starts 5 days before ovulation and ends the day of ovulation.

- The chances for fertility are considered to be highest between days 10 - 17 in the menstrual cycle (with day 1 being the first day of the period and ovulation occurring about 2 weeks later). However, not all women are fertile within that period of time. Women who have a longer or shorter menstrual cycle may have different time periods of fertility.

- Immediately after ovulation, the body temperature increases sharply in about 80% of cases. (Some women can be ovulating normally yet not show this temperature pattern.)

By studying the temperature patterns over a few months, couples can begin to anticipate ovulation and plan their sexual activity accordingly. To avoid losing spontaneity, couples should try to avoid becoming fixated on the chart in scheduling their sexual activity.

Cervical Mucus Method. The cervical mucus method (also called the ovulation method) requires a woman to take a sample (by hand) of her cervical mucus every day for a least a month and to record its quantity, appearance, feel, and to note other physical signs connected with the reproductive system. Cervical mucus changes in predictable ways over the course of each menstrual cycle:

- Six days before ovulation, mucus is affected by estrogen and becomes clear and elastic. Ovulation is likely to occur the last day that mucus has these properties.

- Right after ovulation, mucus is affected by progesterone and is thick, sticky, and opaque.

Once a woman's individual pattern is understood, analyzing cervical mucus can provide a highly accurate guide to fertility.

Calendar Method. The calendar (rhythm method) is considered the least reliable of fertility awareness methods. Women who have very irregular periods may have even less success with this method. In the calendar method, the woman first keeps a record of her menstrual periods for about 6 - 12 months. She then subtracts 18 days from the shortest and 11 days from the longest of the previous menstrual cycles. For example, if a woman's shortest cycle was 26 days and her longest cycle was 30 days, she must abstain from intercourse from day 8 through day 19 of each cycle.

Symptothermal Method. This method combines the temperature, cervical mucus, and calendar methods and is considered the most effective fertility awareness method. In addition, the woman tracks symptoms that may identify her fertile period. These symptoms include changes in the shape of the cervix, breast tenderness, and cramping pain.

Candidacy for Fertility Awareness Methods

Because of the high risk for pregnancy, fertility awareness methods are recommended only for those whose strong religious beliefs prohibit standard contraceptive methods. Couples who are not guided by religious authority, but who simply want a more natural sexual life, may use a barrier contraceptive during the fertile phase and no contraception during the rest of the cycle. However, they should understand the risk of pregnancy will be higher with this method. To be effective against pregnancy, cycle-based methods require not only training, commitment, discipline, and perseverance, but also the cooperation of the male partner. Cycle-based methods are not recommended for women unless they are in a stable, monogamous relationship, and can count on their partner's willing participation.

Fertility-based awareness methods do not protect against sexually transmitted diseases.

Emergency Contraception

Emergency contraception is available to prevent pregnancy in situations such as:

- After sexual assault

- After consensual intercourse in which contraception is not used

- When contraception is used but fails (for instance, when a condom breaks or a diaphragm dislodges)

Emergency contraception is administered as a pill or, less commonly, as an IUD. Emergency contraception should not be used as a substitute for regular routine contraception.

Basics of Emergency Contraception

Emergency contraception most likely works by preventing or delaying the release of an egg from a woman's ovaries. This method prevents pregnancy in the same way as regular birth control pills.

Types of Emergency Contraception

Two emergency contraceptive pills may be bought without a prescription:

- Plan B One-Step is a single tablet that contains 1.5 mg of levonorgestrel.

- Next Choice is taken as two doses, which each contain 0.75 mg of levonorgestrel. Both pills can be taken at the same time or as two separate doses 12 hours apart.

- Either may be taken for up to 5 days after unprotected intercourse.

Ulipristal acetate (ella) is a newer type of emergency contraception pill that requires a prescription from a health care provider.

- Ulipristal is taken as a single tablet.

- It may be taken up to 5 days after unprotected sex.

Two other methods that may be used to prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex are:

- Birth control pills. Talk to your health care provider about the correct dosage. In general, you must take 2 - 5 birth control pills at the same time to have the same protection.

- A copper-releasing intrauterine device (IUD) may be used as an alternative emergency contraception method. It must be inserted by your health care provider within 5 days of having unprotected sex. Your doctor can remove it after your next period, or you may choose to leave it in place to provide ongoing birth control.

More About Emergency Contraceptive Pills

Women ages 17 and older can buy Plan B One-Step and Next Choice at a pharmacy without a prescription or visit to the doctor. Younger girls need to contact a health care provider to get a prescription for these pills.

Emergency contraception works best when you use it within 24 hours of having sex. However, it may still prevent pregnancy for up to 5 days after you first had sex.

Emergency contraception may cause side effects. Most are mild. They may include:

- Changes in menstrual bleeding

- Fatigue

- Headache

- Nausea and vomiting

After you use emergency contraception, your next menstrual cycle may start earlier or later than usual. Your menstrual flow may be lighter or heavier than usual.

- Most women get their next period within 7 days of the expected date.

- If you do not get your period within 3 weeks after taking emergency contraception, you might be pregnant. Contact your health care provider.

Sometime, emergency contraception does not work. However, research suggests that emergency contraceptives have no long-term effects on the pregnancy or developing baby.

Other Important Facts

You should not use emergency contraception if:

- You think you have been pregnant for several days

- You have vaginal bleeding for an unknown reason (talk to your health care provider first)

You may be able to use emergency contraception even if you cannot regularly take birth control pills. Talk to your health care provider about your options.

Emergency contraception should not be used as a routine birth control method. It is less effective at preventing pregnancies than most types of birth control.

Female Sterilization

Female surgical sterilization (also called tubal sterilization, tubal ligation, and tubal occlusion) is a permanent method of contraception. It offers lifelong protection against pregnancy.

Basics of Female Sterilization

Female surgical sterilization procedures block the fallopian tubes and thereby prevent sperm from reaching and fertilizing the eggs. The ovaries continue to function normally, but the eggs they release break up and are harmlessly absorbed by the body. Tubal sterilization is performed in a hospital or outpatient clinic under local or general anesthesia.

Sterilization does not cause menopause. Menstruation continues as before, with usually very little difference in length, regularity, flow, or cramping. Sterilization does not offer protection against sexually transmitted diseases.

Specific Tubal Sterilization Techniques

Laparoscopy. Laparoscopy is the most common surgical approach for tubal sterilization:

- The procedure begins with a tiny incision in the abdomen in or near the navel. The surgeon inserts a narrow viewing scope called a laparoscope through the incision.

- A second small incision is made just above the pubic hairline, and a probe is inserted.

- Once the tubes are found, the surgeon closes them using different methods: clips, tubal rings, or electrocoagulation (using an electric current to cauterize and destroy a portion of the tube).

- Laparoscopy usually takes 20 - 30 minutes and causes minimal scarring. The patient is often able to go home the same day and can resume intercourse as soon as she feels ready.

Minilaparotomy. Minilaparotomy does not use a viewing instrument and requires an abdominal incision, but it is small -- about 2 inches long. The tubes are tied and cut. Generally speaking, minilaparotomy is preferred for women who choose to be sterilized right after childbirth, while laparoscopy is preferred at other times. Minilaparotomy usually takes about 30 minutes to perform. Women who undergo minilaparotomy typically need a few days to recover and can resume intercourse after consulting their doctor.

Essure. The Essure method uses a small spiral-like device to block the fallopian tube. Unlike tubal ligation, the Essure procedure does not require incisions or general anesthesia. It can be performed in a doctor’s office and takes about 45 minutes. A specially trained doctor uses a viewing instrument called a hysteroscope to insert the device through the vagina and into the uterus, and then up into the fallopian tube. Once the device is in place, it expands inside the fallopian tubes. During the next 3 months, scar tissue forms around the device and blocks the tubes. This results in permanent sterilization.

Candidacy for Female Sterilization

Before undergoing sterilization, a woman must be sure that she no longer wants to bear children and will not want to bear children in the future, even if the circumstances of her life change drastically. She must also be aware of the many effective contraceptive choices available. Possible reasons for choosing female sterilization procedures over reversible forms of contraception include:

- Not wanting children and being unable to use other methods of contraception

- Health problems that make pregnancy unsafe

- Genetic disorders

If married, both partners should completely agree that they no longer want to have children and should also have ruled out vasectomy for the man. Vasectomy is a simple procedure that has a lower failure rate than female surgical sterilization, carries fewer risks, and is less expensive. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #37: Vasectomy.]

Even if all these factors are present, a woman must consider her options carefully before proceeding. Women at highest risk for regretting sterilization include:

- Women who are younger at the time of sterilization

- Women who had the procedure immediately after a vaginal delivery

- Women who had the procedure within 7 years of having their youngest child

- Women in lower income groups

If a woman changes her mind and wants to become pregnant, a reversal procedure is available, but it is very difficult to perform and requires an experienced surgeon. Subsequent pregnancy rates after reversal depend on the surgeon’s skill, the age of the woman, and, to a lesser degree, her weight and the length of time between the tubal ligation and the reversal procedure. Not all insurance carriers cover the cost of reversal.

Advantages of Female Sterilization

Women who choose sterilization no longer need to worry about pregnancy or cope with the distractions and possible side effects of contraceptives. Sterilization does not impair sexual desire or pleasure, and many people say that it actually enhances sex by removing the fear of unwanted pregnancy.

Disadvantages and Complications of Female Sterilization

- Failure is rare, less than 1%, but can occur. More than half of these pregnancies are ectopic, which require surgical treatment.

- After any of the procedures, a woman may feel tired, dizzy, nauseous, bloated, or gassy, and may have minor abdominal and shoulder pain. Usually these symptoms go away in 1 - 3 days.

- Serious complications from female surgical sterilization are uncommon and are most likely to occur with abdominal procedures. These rare complications include bleeding, infection, or reaction to the anesthetic.

Resources

- www.nichd.nih.gov -- National Institute of Child Health and Human Development

- www.plannedparenthood.org -- Planned Parenthood

- http://ec.princeton.edu -- Emergency Contraception Website

- www.acog.org -- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

- www.guttmacher.org -- The Alan Guttmacher Institute

- www.arhp.org -- Association of Reproductive Health Professionals

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 112: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 May;115(5):1100-9.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Jul;118(1):184-96.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion no. 539: adolescents and long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Oct;120(4):983-8.

Blythe MJ and Diaz A. Contraception and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007; 120(5): 1135-48.

Castellsagué X, Díaz M, Vaccarella S, de Sanjosé S, Muñoz N, Herrero R, et al. Intrauterine device use, cervical infection with human papillomavirus, and risk of cervical cancer: a pooled analysis of 26 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011 Oct;12(11):1023-31. Epub 2011 Sep 12.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update to CDC's U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010: revised recommendations for the use of contraceptive methods during the postpartum period. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011 Jul 8;60(26):878-83.

Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, Cheng L, Trussell J. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod. 2012 Jul;27(7):1994-2000. Epub 2012 May 8.

Cole JA, Norman H, Doherty M, Walker AM. Venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and stroke among transdermal contraceptive system users. Obstet Gynecol. 2007 Feb;109(2 Pt 1): 339-46.

Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer, Beral V, Doll R, Hermon C, Peto R, Reeves G. Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet. 2008 Jan 26;371(9609): 303-14.

Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives: intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Mar;117(3):705-19.

Gallo MF, Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Schulz KF, Helmerhorst FM. Combination contraceptives: effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Sep 7;(9):CD003987.

Hannaford PC, Selvaraj S, Elliott AM, Angus V, Iversen L, Lee AJ. Cancer risk among users of oral contraceptives: cohort data from the Royal College of General Practitioner's oral contraception study. BMJ. 2007;335(7621): 651.

Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, Celum C, Mugo N, Were E, et al. Use of hormonal contraceptives and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011 Oct 3. [Epub ahead of print]

Jick SS, Hernandez RK. Risk of non-fatal venous thromboembolism in women using oral contraceptives containing drospirenone compared with women using oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel: case-control study using United States claims data. BMJ. 2011 Apr 21;342:d2151. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2151.

Kaunitz AM, Arias R and McClung M. Bone density recovery after depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injectable contraception use. Contraception. 2008;77(2): 67-76.

Lopez LM, Grimes DA, Gallo MF, Schulz KF. Skin patch and vaginal ring versus combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 Mar 17;3:CD003552.

Machado RB, Pereira AP, Coelho GP, Neri L, Martins L, Luminoso D. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of migraine in users of combined oral contraceptives. Contraception. 2010 Mar;81(3):202-8. Epub 2009 Oct 28.

Mosher WD, Jones J. Use of Contraception in the United States: 1982-2008. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 23 (29). May 2010.

O'Brien PA, Kulier R, Helmerhorst FM, Usher-Patel M and d'Arcangues C. Copper-containing, framed intrauterine devices for contraception: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Contraception. 2008;77(5): 318-27.

Parkin L, Sharples K, Hernandez RK, Jick SS. Risk of venous thromboembolism in users of oral contraceptives containing drospirenone or levonorgestrel: nested case-control study based on UK General Practice Research Database. BMJ. 2011 Apr 21;342:d2139. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2139.

Peterson HB. Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol, 2008;111(1): 189-203.

Power J, French R and Cowan F. Subdermal implantable contraceptives versus other forms of reversible contraceptives or other implants as effective methods of preventing pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3): CD001326.

Prager S and Darney PD. The levonorgestrel intrauterine system in nulliparous women. Contraception. 2007;75(6 Suppl): S12-5.

Roumen FJ. The contraceptive vaginal ring compared with the combined oral contraceptive pill: a comprehensive review of randomized controlled trials. Contraception. 2007;75(6): 420-9.

Rosenberg L, Zhang Y, Constant D, Cooper D, Kalla AA, Micklesfield L, et al. Bone status after cessation of use of injectable progestin contraceptives. Contraception. 2007;76(6): 425-31.

Schrager SB. DMPA's effect on bone mineral density: A particular concern for adolescents. J Fam Pract. 2009 May;58(5):E1-8.

Shufelt CL, Bairey Merz CN. Contraceptive hormone use and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Jan 20;53(3):221-31.

Trenor CC 3rd, Chung RJ, Michelson AD, Neufeld EJ, Gordon CM, Laufer MR, et al. Hormonal contraception and thrombotic risk: a multidisciplinary approach. Pediatrics. 2011 Feb;127(2):347-57. Epub 2011 Jan 3.

Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Buckel C, Madden T, Allsworth JE, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012 May 24;366(21):1998-2007.

|

Review Date:

12/24/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |