Systemic lupus erythematosus

Highlights

Systematic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) Overview

SLE is an autoimmune disease that causes a chronic inflammatory condition. The inflammation triggered by SLE can affect many organs in the body, including skin, joints, kidneys, lung, and nervous system. Women (especially African-American and Asian women) have a higher risk than men for developing SLE.

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Patients with SLE can have a wide range of symptoms. The most common symptoms are joint pain, skin rash, and fever. Symptoms can develop slowly or appear suddenly. Many patients with SLE have “flares,” in which symptoms suddenly worsen and then settle down for long periods of time. Diagnosing SLE is complicated because symptoms vary widely and can resemble other conditions. A doctor will base an SLE diagnosis on certain specific criteria including symptom history and the results of blood tests for antinuclear antibodies.

Treatment

No drug can cure SLE, but many different drugs can help control symptoms and relieve discomfort. The choice of drugs depends on the severity of the condition as well as other factors. Patients with mild SLE may be helped by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) while patients with more severe SLE may require corticosteroids or immunosuppressants. Researchers are working to develop new drugs and treatments for SLE.

New Drug Approval: The First New Lupus Drug in 50 Years

In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new drug called belimumab (Benlysta). Belimumab is the first drug developed specifically for treating SLE and the first new lupus treatment in over 50 years. Belimumab is a biologic monoclonal antibody drug that is used along with standard drug treatments for patients with active lupus. Unlike other lupus drugs, which come in pill form, belimumab is given as a monthly intravenous infusion. Unfortunately, it does not seem to be effective in African-American patients.

Living with SLE

Patients can make lifestyle changes to help cope with SLE. These include:

- Avoiding excessive sunlight exposure, and wear sunscreen (ultraviolet light is the one of the main triggers of flares)

- Getting plenty of rest (fatigue is another common SLE symptom)

- Engaging in regular light-to-moderate exercise to help fight fatigue and heart disease, and to keep joints flexible

- Not smoking and avoiding exposure to second-hand tobacco smoke

Introduction

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, often life-long, autoimmune disease. It can be mild to severe, and affects mostly women. SLE may affect various parts of the body, but it most often manifests in the skin, joints, blood, and kidneys. The name describes the disease:

- Systemic is used because the disease can affect organs and tissue throughout the body.

- Lupus is Latin for wolf. It refers to the rash that extends across the bridge of the nose and upper cheekbones and was thought to resemble a wolf bite.

- Erythematosus is from the Greek word for red and refers to the color of the rash.

There are several different forms of lupus. SLE is the most common type and is the type of lupus that can lead to serious systemic complications. Other forms of lupus include:

- Cutaneous lupus erythematosus refers to lupus that is confined to the skin and does not affect other parts of the body. About 10% of people with this type of lupus go on to develop SLE. Discoid lupus erythematosus is a type of cutaneous lupus that produces a potentially scarring disc-shaped rash on the face, scalp, or ears.

- Drug-induced lupus is a temporary and mild form of lupus caused by certain prescription medications. They include some types of high blood pressure drugs (such as hydralazine, ACE inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers) and diuretics (hydrochlorothiazide). Symptoms resolve once the medication is stopped.

- Neonatal lupus is a rare condition that sometimes affects infants born to mothers who have SLE. Babies with neonatal lupus are born with skin rash, liver problems, and low blood counts and may develop heart problems.

Causes

Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disorder. In a normal immune system, the body releases proteins (antibodies) to fight viruses, toxins and other potentially harmful foreign substances (antigens). With lupus and other autoimmune diseases, the immune system does not work properly. It produces autoantibodies that mistakenly attack and destroy the body’s own healthy cells and tissue. These autoantibodies also trigger inflammation, which can lead to organ damage.

Autoantibodies called antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are detectable in most, although not all, patients with SLE. Tests for the presence of ANA are used as part of the diagnostic work-up for the condition. (For more information, see “ANA Tests” in Diagnosis section of this report.)

Scientists do not know exactly what causes the abnormal immune response associated with autoimmune disorders. It is most likely a combination of genetic and environmental factors. People who develop an autoimmune disease may have a genetic predisposition that is triggered by some environmental factor such as sunlight, stress hormones, or viruses. It does not appear that one gene alone is responsible for lupus. Researchers estimate that 20 - 100 different genetic factors make a person susceptible to SLE.

Risk Factors

Gender

About 90% of lupus patients are women, most diagnosed when they are in their childbearing years. Hormones may be an explanation. After menopause, women are only 2.5 times as likely as men to contract SLE. Flares also become somewhat less common after menopause in women who have chronic SLE.

Age

Most people develop SLE between the ages of 15 - 44. About 15% of people who are eventually diagnosed with lupus develop symptoms before age 18.

Race and Ethnicity

African-Americans are three to four times more likely to develop the disease than Caucasians and to have severe complications. Hispanics and Asians are also more susceptible to the disease.

Family History

A family history plays a strong role in SLE. A brother or sister of a patient with the disorder has 20 times the risk as someone without an immediate family member with SLE.

Environmental Triggers

In genetically susceptible people, there are various external factors that can trigger symptoms (flares). Possible SLE triggers include colds, fatigue, stress, chemicals, sunlight, and certain drugs.

Viruses. Some research suggests an association between Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the cause of mononucleosis, and increased risk of lupus, particularly for African-Americans.

Sunlight. Ultraviolet (UV) rays found in sunlight are important SLE triggers. UV light is categorized as UVB or UVA depending on the length of the wave. Shorter UVB wavelengths cause the most harm.

Smoking. Smoking may be a risk factor for triggering SLE and can increase the risk for skin and kidney problems in women who have the disease.

Chemicals. While no chemical has been definitively linked to SLE, occupational exposure to crystalline silica has been studied as a possible trigger. (Silicone breast implants have been investigated as a possible trigger of autoimmune diseases, including SLE. The weight of evidence to date, however, finds no support for this concern.) Some prescription medications are associated with a temporary lupus syndrome (drug-induced lupus), which resolves when these drugs are stopped.

Hormone Replacement Therapy. Premature menopause, and its accompanying symptoms (such as hot flashes), is common in women with SLE. Hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which is used to relieve these symptoms, increases the risk for blood clots and heart problems as well as breast cancer. It is not clear whether HRT triggers SLE flares. Women should discuss with their doctors whether HRT is an appropriate and safe choice. Guidelines recommend that women who take HRT use the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible time. Women with SLE who have active disease, antiphospholipid antibodies, or a history of blood clots or heart disease should not use HRT.

Oral Contraceptives. Female patients with lupus used to be cautioned against taking oral contraceptives (OCs) due to the possibility that estrogen could trigger lupus flare-ups. However, recent evidence indicates that OCs are safe, at least for women with inactive or stable lupus. Women who have been newly diagnosed with lupus should avoid OCs. Lupus can cause complications in its early stages. For this reason, women should wait until the disease reaches a stable state before taking OCs. In addition, women who have a history of, or who are at high risk for, blood clots (particularly women with antiphospholipid syndrome) should not use OCs. The estrogen in OCs increases the risk for blood clots.

Complications

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) can cause complications throughout the body.

Complications of the Blood

Almost 85% of patients with SLE experience problems associated with abnormalities in the blood.

Anemia. About half of patients with SLE are anemic. Causes include:

- Iron deficiencies resulting from excessive menstruation

- Iron deficiencies from gastro-intestinal bleeding caused by some of the treatments

- A specific anemia called hemolytic anemia, which destroys red blood cells

- Anemia of chronic disease

Hemolytic anemia can occur with very high levels of the anticardiolipin antibody. It can be chronic or develop suddenly and be severely (acute).

Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Between 34 - 42% of patients with SLE have antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). This is a disorder of blood coagulation related to the presence of autoantibodies called lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin. APS can cause blood clots, which most often occur in the deep veins of the legs, a condition called deep vein thrombosis. Blood clots can increase the risk for stroke and pulmonary embolism (clots in the lungs). Patients with APS are also at high risk for pregnancy complications, including miscarriage (see Pregnancy Complications below).

Vasculitis. Vasculitis is an inflammation of the blood vessels. If it becomes severe, it can cause blood to stop flowing to organs and tissues, resulting in potentially life-threatening complications.

Thrombocytopenia. In thrombocytopenia, antibodies attack and destroy blood platelets. In such cases, blood clotting is impaired, which causes bruising and bleeding from the skin, nose, gums, or intestines.

Leukopenia and Neutropenia. These conditions cause a drop in the number of white blood cells. They are very common in lupus, but the condition is usually harmless unless the reductions are so severe that they leave the patient vulnerable to infections.

Blood Cancers. Patients with SLE and other autoimmune disorders have a greater risk for developing lymph system cancers such as Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL).

Heart Complications

The risk for cardiovascular disease, heart attack, and stroke is much higher than average in patients with SLE, and heart disease is a primary cause of death. The chronic inflammation associated with SLE can cause plaque build-up in the heart’s arteries (atherosclerosis), which can lead to coronary heart disease and heart attack. SLE also affects blood vessels and circulation. In addition, SLE treatments (particularly corticosteroids) can affect cholesterol, weight, and other factors that impact the heart. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #03: Coronary artery disease.].

Patients with SLE have a higher risk for developing the following conditions, which put them at risk for heart attack or stroke:

- Atherosclerosis, or plaque buildup in the arteries

- Unhealthy cholesterol and lipid (fatty molecules) levels

- High blood pressure, often associated with kidney damage and corticosteroid treatments

- Heart failure

- Pericarditis, inflammation of the tissue surrounding the heart

- Endocarditis, inflammation in the lining of the heart

- Myocarditis, inflammation of the heart muscle itself

- Coronary vasculitis, inflammation of the blood vessels of the heart

Lung Complications

SLE affects the lungs in several ways:

- Inflammation of the membrane lining the lung (pleurisy) is the most common problem, which can cause shortness of breath and coughing.

- In some cases, fluid accumulates, a condition called pleural effusion.

- Inflammation of the lung tissue itself is called lupus pneumonitis. It can be caused by infections or by the SLE inflammatory process. Symptoms are the same in both cases: fever, chest pain, labored breathing, and coughing. Rarely, lupus pneumonitis becomes chronic and causes scarring in the lungs, which reduces their ability to deliver oxygen to the blood.

- A very serious and rare condition called pulmonary hypertension occurs when high pressure develops as a result of damage to the blood vessels of the lungs.

Kidney Complications (Lupus Nephritis)

Kidney complications are common in SLE. Inflammation of the kidneys (lupus nephritis) typically develops within 5 years after lupus symptoms begin. In its early stages, lupus nephritis can cause fluid build-up leading to swelling in the extremities (feet, legs, hands, arms) and overall weight gain. If left untreated, lupus nephritis may progress to complete kidney failure (end-stage renal disease).

Central Nervous System Complications

Nearly all patients with SLE report some symptoms relating to problems that occur in the central nervous system (CNS), which includes the spinal cord and the brain.

Symptoms vary widely and may overlap with psychiatric or neurologic disorders. They may also be caused by of some medications used for treating SLE.

The most serious CNS disorder is inflammation of the blood vessels in the brain (CNS vasculitis), which occurs in about 10% of patients with SLE. Fever, seizures, psychosis, and even coma can occur. Other CNS side effects include:

- Irritability

- Emotional disorders (anxiety, depression)

- Mild impairment of concentration and memory

- Migraine and tension headaches

- Problems with the reflex systems, sensation, vision, hearing, and motor control

Infections

Infections are a common complication and a major cause of death in all stages of SLE. Patients are not only prone to the ordinary bacterial and viral infections, but they are also susceptible to fungal and parasitic infections, which are common in people with weakened immune systems. They also face an increased risk for urinary tract, herpes, salmonella, and yeast infections. Corticosteroid and immunosuppressants, treatments used for SLE, also increase the risk for infections, thereby compounding the problem.

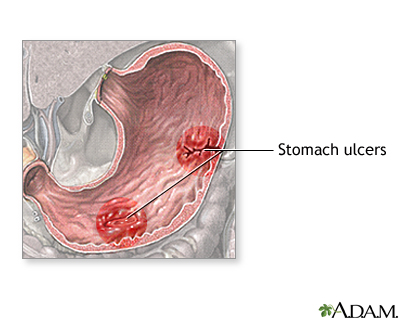

Gastrointestinal Complications

Many patients with SLE suffer gastrointestinal problems, including nausea, weight loss, mild abdominal pain, diarrhea, and gastroesophageal reflux disorder (heartburn). SLE can also affect organs located in the gastrointestinal system, such as the liver, gallbladder, pancreas, and bile ducts.

Joint, Muscle, and Bone Complications

Patients with SLE often experience muscle aches and weakness. Lupus can also cause pain, stiffness, and swelling in the joints. However, unlike rheumatoid arthritis, the arthritis caused by SLE almost never leads to destruction or deformity of joints. Patients with SLE also commonly experience reductions in bone mass density (osteoporosis) and have a higher risk for fractures, whether or not they are taking corticosteroids (which can increase the risk for osteoporosis). Women who have SLE should have regular bone mineral density scans to monitor bone health.

Eye Complications

Many patients with SLE have problems with dry eyes. Retinal vascular lesions (blood vessel damage due to reduced blood flow) are also common and may affect vision. Nerve damage in the eyes can also cause poor vision as well as droopy eyelids.

Pregnancy Complications

Women with lupus face a higher risk for pregnancy complications, including miscarriage, premature birth, and preeclampsia. The risk for miscarriage is highest for patients with antiphospholipid antibodies, which can cause blood clotting in the placenta. Lupus patients with active kidney disease are at increased risk for preeclampsia (a pregnancy complication that includes high blood pressure and fluid build-up). Pregnant women who take corticosteroids face increased risks of gestational diabetes and high blood pressure.

Despite these obstacles, many women with lupus have healthy pregnancies and deliver healthy babies. To increase the odds of a successful pregnancy, it is important for women to plan carefully before becoming pregnant. (See “Pregnancy and SLE” in Treatment section of this report.)

Prognosis

SLE is a chronic and relapsing inflammatory disease. It is marked by periods of remission (no symptoms) that alternate with flares of active disease when symptoms suddenly worsen. Flares tend to diminish after menopause.

Symptom-free periods can sometimes last for years, but the course of SLE is unpredictable and varies greatly from person to person. Some patients have a mild form of lupus with occasional skin rashes, fever, fatigue, or joint and muscle aches. Sometimes lupus remains in a mild form, other times it may progress to a more severe form. Severe lupus involves serious health complications and extensive internal organ damage (such as the heart, lungs, kidneys, and brain).

Because of more effective and aggressive treatment, the prognosis for SLE has improved markedly over the past two decades. Treatment early in the course of the illness that controls the initial inflammation can help to improve long-term outlook. Over 95% of people with lupus survive at least 10 years, and many patients have a normal lifespan.

Symptoms

SLE symptoms may develop slowly over months or years, or they may appear suddenly. Symptoms tend to vary among patients and different symptoms can occur at different times.

Common symptoms of SLE include:

- Joint pain and stiffness, which is often accompanied by swelling and redness. The joints most affected are fingers, wrists, elbows, knees, and ankles.

- Skin rash, including the characteristic “butterfly rash” on the face that extends over the bridge of the nose and cheeks. Rash can also appear on other parts of the face or other skin areas that are exposed to sun.

- Fever

- Extreme fatigue

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite, nausea, and weight loss

- Chest pain

- Bruising

- Menstrual irregularities

- Dry eyes

- Mouth ulcers

- Brittle hair or hair loss

- Painful, pale or purple fingers or toes triggered by cold or stress (Raynaud’s phenomenon)

- Anxiety, depression, forgetfulness, and difficulty concentrating

Conditions with Similar Symptoms

A number of conditions overlap with SLE:

- Scleroderma: Hardening of the skin caused by overproduction of collagen

- Rheumatoid arthritis: Inflammation of the lining of the joints

- Sjögren syndrome: Characterized by dry eyes and dry mouth

- Mixed connective tissue disorder: Similar to SLE, but milder

- Myositis: Inflammation and degeneration of muscle tissues

- Rosacea: Flushed face with pus-filled blisters

- Seborrheic dermatitis: Sores on lips and nose

- Lichen planus: Swollen rash that itches, typically on scalp, arms, legs, or in the mouth

- Dermatomyositis: Bluish-red skin eruptions on face and upper body

- Lyme disease: Bulls-eye rash, joint inflammation, and flu-like symptoms

Diagnosis

SLE can be difficult to diagnose. Symptoms can fluctuate and mimic those of other diseases. A doctor will make a diagnosis of SLE based on symptoms, medical history, physical exam and blood test for antinuclear antibodies. The doctor may also order other types of laboratory tests.

The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) has a classification system for helping doctors diagnose, or exclude, SLE. According to the ACR, at least four of the 11 criteria should be present for a diagnosis of lupus.

ACR Criteria for Diagnosing Systemic Lupus Erythematosus |

1. Butterfly (malar) rash across cheeks and nose |

2. Discoid (skin) rash, which appears as scaly raised red patches |

3. Photosensitivity |

4. Oral (mouth) ulcers |

5. Arthritis in two or more joints; joints will have tenderness and swelling but will not have become deformed |

6. Inflammation of the lining around the lungs (pleuritis) or the heart (endocarditis) |

7. Evidence of kidney disease |

8. Evidence of severe neurologic disease, such as seizures or psychosis |

9. Blood disorders, including low red and white blood cell and platelet counts |

10. Immunologic abnormalities as evidenced by positive tests for anti-double stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA), anti-SM, anti-Ro, and anti-LA antibodies |

11. Positive antinuclear antibody (ANA) test |

Note: A patient must experienced four of the criteria before a doctor can classify the condition as SLE. These criteria, proposed by the American College of Rheumatology, are not exclusive criteria for diagnosis, however. |

Tests for Autoantibodies (ANA Test)

Antinuclear Antibodies (ANAs). A primary test for SLE checks for antinuclear antibodies (ANA), which attack the cell nucleus.

High levels of ANA are found in more than 98% of patients with SLE. Other conditions, however, also cause high levels of ANA, so a positive test is not a definite diagnosis for SLE:

- Antinuclear antibodies may be strongly present in other autoimmune diseases (such as scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, or rheumatoid arthritis).

- They also may be weakly present in about 20 - 40% of healthy women.

- Some drugs can also produce positive antibody tests, including hydralazine, procainamide, isoniazid, and chlorpromazine.

A negative ANA test makes a diagnosis of SLE unlikely but not impossible. High or low concentrations of ANA also do not necessarily indicate the severity of the disease, since antibodies tend to come and go in patients with SLE.

In general, the ANA test is considered a screening test:

- If SLE-like symptoms are present and the ANA test is positive, other tests for SLE will be administered.

- If SLE-like symptoms are not present and the test is positive, the doctor will look for other causes, or the results will be ignored if the patient is feeling healthy.

ANA Subtypes. Doctors may also test for specific ANA subtypes.

- Anti-double stranded DNA (Anti-ds DNA) is more likely to be found only in patients with SLE. It may play an important role in injury to blood vessels found in SLE, and high levels often indicate kidney involvement. Anti-ds DNA levels tend to fluctuate over time and may even disappear.

- Anti-Sm antibodies are also usually found only with SLE. Levels are more constant and are more likely to be detected in African-American patients. Although many lupus patients may not have this antibody, its presence almost always indicates SLE.

- When the ANA is negative but the diagnosis is still strongly suspected, a test for anti-Ro (also called anti-SSA) and anti-La (also called anti-SSB) antibodies may identify patients with a rare condition called ANA negative, Ro lupus. These autoantibodies may be involved in the sun-sensitive rashes experienced by patients with SLE and are also found in association with neonatal lupus syndrome, in which a pregnant mother's antibodies cross the placenta and cause inflammation in the developing child's skin or heart.

Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Up to half of patients with SLE have antiphospholipid antibodies, which increase the risk for blood clots, strokes, and pregnancy complications. If a doctors suspects someone with SLE has blood abnormalities, tests may be able to detect the presence of the two major antiphospholipid antibodies: lupus coagulant antibody and anticardioplin antibody.

As with the ANA, these antibodies have a tendency to appear and disappear. Patients who have these autoantibodies as well as blood clotting problems or frequent miscarriages are diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome (APS), which often occurs in SLE but can also develop independently.

Other Blood Tests

Complement. Blood tests of patients with SLE often show low levels of serum complement, a group of proteins in the blood that aid the body's infection fighters. Individual proteins are termed by the letter "C" followed by a number. Common complement tests measure C3, C4, C1q, and CH50. Complement levels are especially low if there is kidney involvement or other disease activity.

Blood Count. White and red blood cell and platelet counts are usually lower than normal and, depending on severity, are used to determine complications, such as anemia or infection.

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR). An erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR or sed rate) measures how fast red blood cells (erythrocytes) fall to the bottom of a fine glass tube that is filled with the patient's blood. A high sed rate indicates inflammation.

C-Reactive Protein (CRP). High levels of this blood protein indicate inflammation. Like the ESR, the CRP test cannot tell where the inflammation is located or what is causing it.

Skin Tests

If a skin rash is present, the doctor may take a biopsy (a tissue sample) from the margin of a skin lesion. A test known as a lupus band detects immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, which are located just below the outer layer of the tissue sample. They are much more likely to be present with active SLE than with inactive disease.

Tests for Complications of SLE

Kidney Damage and Lupus Nephritis. Kidney damage in patients already diagnosed with SLE may be detected from the following tests:

- Blood tests that measure creatinine, a protein metabolized in muscles and excreted in the urine. High levels suggest kidney damage, although kidney problems can also be present with normal creatinine levels.

- Urine tests to measure protein levels

- Tests for detecting anti-ds DNA antibodies and blood complements.

- A kidney biopsy may be performed to evaluate the extent of kidney damage.

Lung and Heart Involvement. A chest x-ray may be performed to check lung and heart function. An electrocardiogram and an echocardiogram are administered if heart disease is suspected.

Treatment

No treatment cures systemic lupus erythematosus, but many therapies can suppress symptoms and relieve discomfort. There are also different treatments for the complications associated with lupus. Treatment of SLE varies depending on the extent and severity of the disease.

Four drugs are specifically FDA-approved for the treatment of lupus:

- Prednisone

- Aspirin

- Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, generic)

- Belimumab (Benlysta)

Belimumab (Benlysta) is the newest of these drugs. It was approved by the FDA in March 2011. It is the first new lupus drug in over 50 years and the first drug developed specifically for treating lupus. Belimumab is a biologic monoclonal antibody drug that inhibits a protein called B lymphocyte stimulator. Belimumab is given by infusion in a doctor’s office. The other drugs are given as pills taken by mouth.

Other drugs that have not been specifically approved for lupus are also commonly used to treat the condition. Researchers are conducting many investigational drug studies, including trials of new biologic drugs..

Treating Mild Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Less intensive treatments may be effective for symptoms of mild lupus. They include:

- Creams and sunblocks for rashes

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for fever, arthritis, and headache

- Hydroxychloroquine or similar antimalarial drugs for pleurisy, mild kidney involvement, and inflammation of the tissue surrounding the heart

Treating Severe Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

More aggressive treatment is needed if there is serious disease progression, as evidenced by:

- Hemolytic anemia

- Low platelet count with an accompanying rash (thrombocytopenia purpura)

- Major involvement in the lungs or heart

- Significant kidney damage

- Acute inflammation of the small blood vessels in the extremities or gastrointestinal tract

- Severe central nervous system symptoms

The primary approach to treating severe SLE is to suppress the inflammation and overactive immune system with corticosteroids or immunosuppressant drugs.

Treating Specific Complications

The major complications of the disease must be treated as separate disorders, keeping in mind the specific aspects of SLE.

Pregnancy and SLE

Women with lupus who conceive face high-risk pregnancies that increase the risks for themselves and their babies. It is important for women to understand the potential complications and plan accordingly. The most important advice is to try to avoid becoming pregnant when lupus is active. Research suggests that the following factors predict a successful pregnancy:

- Disease state at time of conception. Doctors strongly recommend that women wait to conceive until their disease state has been inactive for at least 6 months.

- Kidney (renal) function. Women should make sure that their kidney function is evaluated prior to conception. Poor kidney function can worsen high blood pressure and cause excess protein in the urine. These complications increase the risk for preeclampsia (high blood pressure doing pregnancy) and miscarriage.

- Lupus-related antibodies. Antiphospholipid and anticardiolipin antibodies can increase the risks for blood clots, preeclampsia, miscarriage, and stillbirths. Anti-SSA and anti-SSB antibodies can increase the risk for neonatal lupus erythematosus, a condition that can cause skin rash and liver and heart damage to the newborn baby. Levels of these antibodies should be tested at the start of pregnancy. Certain medications (aspirin, heparin) and tests (fetal heart monitoring) may be needed to ensure a safe pregnancy.

- Medication use during pregnancy. Women with active disease may need to take low-dose corticosteroids, but women with inactive disease should avoid these drugs. Steroids appear to pose a low risk for birth defects, but can increase a pregnant woman’s risks for gestational diabetes, high blood pressure, infection, and osteoporosis. For patients who need immunosuppressive therapy, azathioprine (Imuran) is an option. Methotrexate (Rheumatrex) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) should not be taken during pregnancy.

Treatment for Mild SLE

Creams and Sunblocks

Creams. Steroid creams are often used for skin lesions. However, many patients with cutaneous lupus do not respond to steroids, particularly if they have eruptions that are caused by sun sensitivity. A cream derived from vitamin A (Tegison) may help some lesions that do not clear up with steroid creams.

Sun Protection. Sun protection is essential. Patients should always use sunblock creams (not just sunscreens) and always wear hats and clothing made of tightly woven fabrics.

Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Common NSAIDs. NSAIDs block prostaglandins, the substances that dilate blood vessels and cause inflammation and pain. They can help relieve joint pain and swelling, and muscle pain. There are dozens of NSAIDs.

- Over-the-counter NSAIDs include aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, generic), naproxen (Aleve, generic), ketoprofen (Actron, Orudis KT, generic).

- Prescription NSAIDs include prescription forms of ibuprofen naproxen and ketoprofen, diclofenac (Voltaren, generic), and tolmetin (Tolectin, generic).

Side Effects. Regular, long-term use of NSAIDs can cause ulcers and gastrointestinal bleeding, which can lead to anemia. To avoid these problems, it’s best to take NSAIDs with food or immediately after a meal. Long-term use of NSAIDs (with the exception of aspirin) can also increase the risk for heart attack and stroke.

Other NSAID side effects may include:

- Upset stomach

- Dyspepsia (burning, bloated feeling in pit of stomach)

- Drowsiness

- Skin bruising

- High blood pressure

- Fluid retention

- Headache

- Rash

- Reduced kidney function

Patients who have kidney problems associated with lupus (lupus nephritis) should be especially cautious about using NSAIDs. Patients with lupus who take NSAIDs on a regular basis should have their liver and kidney function tested every 3 - 4 months.

Antimalarial Drugs

A doctor may prescribe antimalarial drugs for mild SLE when skin problems and joint pains are the predominant symptoms:

- Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil, generic) is the most common antimalarial drug used for lupus. This drug is effective as maintenance therapy to reduce flares in patients with mild or inactive disease. Hydroxychloroquine may help protect against blood clots in people with antiphospholipid syndrome, high cholesterol levels, and bone loss.

- Other antimalarial drugs include chloroquine (Aralen, generic) or quinacrine (Atabrine, generic).

Treatment may start initially with high doses in order to accumulate high levels of the drug in the bloodstream. It is not known exactly why antimalarials work. Some researchers believe they inhibit the immune response, and others think they interfere specifically with inflammation.

Side Effects. Side effects of antimalarials may include:

- Skin rash

- Change in skin color (yellow in the case of quinacrine)

- Gastrointestinal problems

- Headache

- Hair loss

- Muscle aches

- Eye damage

The most serious side effect is damage to the retina, although this is very uncommon at low doses. Eye damage after taking hydroxychloroquine is reversible when caught in time and treated, but it is not reversible if the damage develops after taking chloroquine. An eye exam is advisable about every 6 months.

Antimalarials may also be used in combination with other anti-SLE drugs, including immunosuppressants and corticosteroids. It should be noted that smoking significantly reduces the effectiveness of antimalarial drugs.

Treatment for Severe SLE

Corticosteroids

Severe SLE is treated with corticosteroids, also called steroids, which suppress the inflammatory process. Steroids can help relieve many of the complications and symptoms, including anemia and kidney involvement.

Oral prednisone (Deltasone, Orasone, generic) is usually prescribed. Other drugs include methylprednisolone (Medrol, Solumedrol, generic), hydrocortisone, and dexamethasone (Decadron, generic).

Some people need to take oral prednisone for only a short time; others may require it for a long duration. An intravenous administration of methylprednisolone using "pulse" therapy for 3 days can help reduce flare-ups in the joints. Combinations with other drugs, particularly immunosuppressants, may be beneficial.

Regimens vary widely, depending on the severity and location of the disease. Most patients with SLE can eventually function without prednisone, although some may have to choose between the long-term toxicity of corticosteroids and the complications of active disease.

Side Effects of Long-Term Oral Corticosteroids. Unfortunately, serious and even life-threatening complications are associated with long-term oral steroid use:

- Osteoporosis

- Cataracts

- Glaucoma

- Diabetes

- Fluid retention

- Susceptibility to infections

- Weight gain

- High blood pressure

- Acne

- Excess hair growth

- Wasting of the muscles

- Menstrual irregularities

- Irritability

- Insomnia

- Psychosis

Withdrawal from Long-Term Use of Oral Corticosteroids. Long-term use of oral steroid medications suppresses secretion of natural steroid hormones by the adrenal glands. After withdrawal from these drugs, this adrenal suppression persists and it can take the body a while (sometimes up to a year) to regain its ability to produce natural steroids again.

No one should stop taking any steroids without first consulting a doctor, and if steroids are withdrawn, regular follow-up monitoring is necessary. Patients should discuss with their doctors measures for preventing adrenal insufficiency during withdrawal, particularly during stressful times, when the risk increases.

Immunosuppressant Drugs

Drugs known as immunosuppressants are often used, either alone or with corticosteroids, for very active SLE. Immunosuppressants are particularly recommended when kidney or neurologic involvement or acute blood vessel inflammation is present. These drugs suppress the immune system by damaging cells that grow rapidly, including those that produce antibodies. About a third of patients with SLE take immunosuppressants at some point in the course of the disease.

Specific Immunosuppressants. The most common immunosuppressants are:

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, generic) used to be considered the gold standard of treatment for lupus kidney disease (lupus nephritis). Cyclophosphamide is given intravenously and is sometimes used in combination with corticosteroids or other drugs. It has been used for lupus since the 1970s. Side effects are very severe and include nausea, vomiting, hair loss, infertility, and infections.

- Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept, generic) and mycophenolate acid (Myfortic) are now becoming the new standard. Many recent studies have shown that mycophenolate works better than cyclophosphamide and causes far fewer severe side effects (diarrhea is the main side effect). Unlike cyclophosphamide, it is taken by mouth. Most doctors now recommend mycophenalate mofetil as a first-line treatment for newly diagnosed patients with mild or moderate lupus kidney disease. It may not be appropriate for patients with kidney failure or rapidly progressing kidney disease. Mycophenolate should not be used during pregnancy as it can cause miscarriage and birth defects.

- Azathioprine (Imuran, generic) has fewer side effects but is less effective than other immunosuppressants.

- Cyclosporine (Sandimmune, generic) has been used for years, mostly for kidney complications associated with SLE. High blood pressure is common, however, with this drug.

The most frequent side effects of immunosuppressants include:

- Stomach and intestinal problems

- Skin rash

- Mouth sores

- Hair loss

Serious side effects of immunosuppressants include:

- Low blood cell counts

- Anemia

- Menstrual irregularity

- Early menopause

- Ovarian failure

- Infertility

- Herpes zoster (shingles)

- Liver and bladder toxicity

- Increased risk of cancer

- Kidney damage

In general, immunosuppressants should not be used alone unless corticosteroids are ineffective or inappropriate.

Biologic Drugs

Belimumab (Benlysta) is a monoclonal antibody drug that is used along with standard lupus drug treatments such as corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressants, and NSAIDs. Approved in 2011, belimumab is the first new lupus drug in over 50 years and was the first drug developed specifically for treating lupus. The drug works by targeting and reducing the abnormal B cells that are thought to play a role in lupus.

Belimumab is given directly into a vein by intravenous infusion. The infusion is given in a doctor’s office or other clinical setting and takes about an hour. The patient receives an infusion every two weeks for the first three treatments. After that, the patient receives an infusion once every four weeks.

In clinical studies, patients who received belimumab along with standard therapies had less disease activity than those who received a placebo. The studies suggested that belimumab might reduce the likelihood of severe flares and may possibly help patients reduce their doses of steroid medicine. However, in these studies, African-Americans and other patients of African descent did not seem to respond to belimumab. Additional studies are being conducted to determine if belimumab is safe and effective for these patients.

Belimumab has many side effects. The most common ones are nausea, diarrhea, and fever. Serious side effects may include infections, heart problems, and depression including thoughts of suicide. The drug is very expensive and some insurers may not pay for it.

Lifestyle Changes

Staying Active

People with SLE should try to maintain a healthy and active lifestyle. Light-to-moderate exercise, interspersed with rest periods, is good for the heart, helps fight depression and fatigue, and can help keep joints flexible.

Preventing Infections

Patients should be sure they are fully immunized and should minimize their exposure to crowds or people with contagious illnesses. Careful hygiene, including dental hygiene, is also important.

Avoiding SLE Triggers

It is very important that patients with SLE avoid excessive exposure to sunlight. Simple preventive measures include avoiding overexposure to ultraviolet rays and wearing protective clothing and sunblocks. There is some concern that allergy shots may cause flare ups in certain cases. Patients who may benefit from them should discuss risks and benefits with an SLE specialist. In general, patients with SLE should use only hypoallergenic cosmetics or hair products. Cigarette smoking is a major trigger for SLE flares. It is very important that patients with SLE not smoke and avoid exposure to second-hand cigarette smoke.

Reducing Stress

Chronic stress has profound physical effects and influences the progression of SLE. Getting adequate rest of at least 8 hours and possibly napping during the day may be helpful. Maintaining social relationships and healthy activities may also help prevent the depression and anxiety associated with the disease.

Resources

- www.lupus.org -- Lupus Foundation of America

- www.lupusny.org -- SLE Lupus Foundation

- www.niams.nih.gov -- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases

- www.rheumatology.org -- American College of Rheumatology

- www.lupusresearchinstitute.org -- Lupus Research Institute

References

Bernatsky S, Ramsey-Goldman R, Isenberg D, Rahman A, Dooley MA, Sibley J, et al. Hodgkin's lymphoma in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007 May;46(5):830-2. Epub 2007 Jan 25.

Bertsias G, Ioannidis JP, Boletis J, Bombardieri S, Cervera R, Dostal C, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Report of a Task Force of the EULAR Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutics. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Feb;67(2):195-205. Epub 2007 May 15.

Crosbie D, Black C, McIntyre L, Royle PL, Thomas S. Dehydroepiandrosterone for systemic lupus erythematosus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD005114.

Crow MK. Collaboration, genetic associations, and lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2008 Feb 28;358(9):956-61. Epub 2008 Jan 20.

Crow MK. Systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Goldman L, Schafer AI, eds. Cecil Medicine. 24th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011:chap 274.

Culwell KR, Curtis KM, del Carmen Cravioto M. Safety of contraceptive method use among women with systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Aug;114(2 Pt 1):341-53

D'Cruz DP, Khamashta MA, Hughes GR. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Lancet. 2007 Feb 17;369(9561):587-96.

Hahn BH, Tsao BP. Pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus. In: Firestein GS, Budd RC, Harris ED Jr, et al, eds. Kelley's Textbook of Rheumatology. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2008:chap 74.

Khamashta MA. Systemic lupus erythematosus and pregnancy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2006 Aug;20(4):685-94.

Klareskog L, Padyukov L, Alfredsson L. Smoking as a trigger for inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007 Jan;19(1):49-54.

Mackillop LH, Germain SJ, Nelson-Piercy C. Systemic lupus erythematosus. BMJ. 2007 Nov 3;335(7626):933-6.

Rahman A, Isenberg DA. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2008 Feb 28;358(9):929-39.

Ruiz-Irastorza G, Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Khamashta MA. Clinical efficacy and side effects of antimalarials in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 January; 69 (01):20-28.

Sabahi R, Anolik JH. B-cell-targeted therapy for systemic lupus erythematosus. Drugs. 2006;66(15):1933-48.

Salmon JE, Roman MJ. Subclinical atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Am J Med. 2008 Oct;121(10 Suppl 1):S3-8.

Sánchez-Guerrero J, González-Pérez M, Durand-Carbajal M, Lara-Reyes P, Jiménez-Santana L, Romero-Díaz J, et al. Menopause hormonal therapy in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007 Sep;56(9):3070-9.

Tsokos GC. Systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2011 Dec 1;365(22):2110-21.

|

Review Date:

2/7/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |