Peptic ulcers

Highlights

Overview

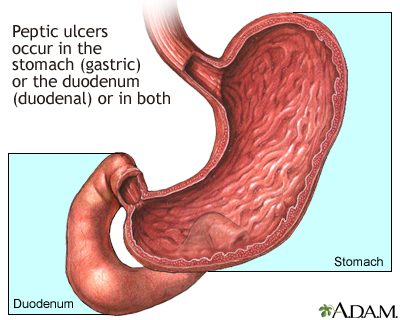

- More than 6 million people in the United States have peptic ulcer disease.

- A peptic ulcer is an open sore or raw area that tends to develop in one of two places:

- The lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer)

- The upper part of the small intestine -- the duodenum (duodenal ulcer)

- Ulcers develop when digestive juices produced in the stomach, intestines, and digestive glands damage the lining of the stomach or duodenum.

- In 1982 two Australian scientists identified the bacteria H. pylori as the main cause of peptic ulcers.

- Long-term use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is the second most common cause of ulcers.

- Certain drugs other than NSAIDs may aggravate ulcers.

- Peptic ulcers can have a major effect on a patient's quality of life and finances. Research finds that complications of peptic ulcer disease can cost from $1,800 to more than $25,000 per patient.

New Research

- Some NSAIDs pose greater risks than others for ulcers and bleeding. Research finds that taking a COX-2-selective NSAID (celecoxib) poses less gastrointestinal risk than a non-selective NSAID (such as diclofenac) plus a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). However, coxibs carry a higher risk for heart attack and stroke than NSAIDs.

- Endoscopy is recommended for patients over age 50 who have new symptoms of peptic ulcers, as well as for patients under age 50 who have alarm symptoms (such as unintended weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, or swallowing problems). Patients under age 50 who don't have alarm symptoms can be tested for H. pylori infection and treated if they are positive. Endoscopy may also be performed if peptic ulcer symptoms don't improve with treatment.

Risk Factors Include

- About 10 - 15% of people who are infected with H. pylori develop peptic ulcer disease. Other factors must also be present to trigger ulcers.

- Anyone who uses NSAIDs regularly is at risk for gastrointestinal problems.

- Although stress is no longer considered to be a cause of ulcers, some studies still suggest that stress may predispose a person to ulcers or prevent existing ulcers from healing.

Medication Warnings

- Studies have found that taking PPIs with the blood thinner clopidogrel (Plavix) reduces the effectiveness of this blood thinner by nearly 50%.

- A warning added in May 2012 cautions that using certain PPIs with methotrexate, a drug commonly used to treat certain cancers and autoimmune conditions, can lead to elevated levels of methotrexate in the blood, causing toxic side effects.

Introduction

More than 6 million people in the United States have a peptic ulcer -- an open sore or raw area that tends to develop in one of two places:

- The lining of the stomach (gastric ulcer)

- The upper part of the small intestine -- the duodenum (duodenal ulcer)

In the U.S., duodenal ulcers are three times more common than gastric ulcers.

Ulcers average between one-quarter and one-half inch in diameter. They develop when digestive juices produced in the stomach, intestines, and digestive glands damage the lining of the stomach or duodenum.

The two important components of digestive juices are hydrochloric acid and the enzyme pepsin. Both substances are critical in the breakdown and digestion of starches, fats, and proteins in food. They play different roles in ulcers:

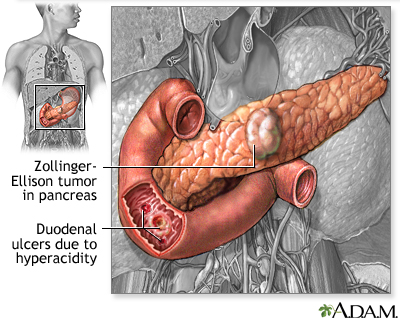

- Hydrochloric acid. A common misperception is that excess hydrochloric acid, which is secreted in the stomach, is solely responsible for producing ulcers. Patients with duodenal ulcers do tend to have higher-than-normal levels of hydrochloric acid, but most patients with gastric ulcers have normal or lower-than-normal acid levels. Some stomach acid is actually important for protecting against H. pylori, the bacteria that cause most peptic ulcers. [Note: An exception is ulcers that occur in Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, a rare genetic condition in which tumors in the pancreas or duodenum secrete very high levels of gastrin, the hormone that stimulates the release of hydrochloric acid.]

- Pepsin. Pepsin, an enzyme that breaks down proteins in food, is also an important factor in the formation of ulcers. Because the stomach and duodenum are composed of protein, they are susceptible to the actions of pepsin.

Fortunately, the body has a defense system to protect the stomach and intestines against these two powerful substances:

- The mucus layer, which coats the stomach and duodenum, forms the first line of defense.

- Bicarbonate, which the mucus layer secretes, neutralizes digestive acids.

- Hormone-like substances called prostaglandins help widen the blood vessels in the stomach, to ensure good blood flow and protect against injury. Prostaglandins are also believed to stimulate bicarbonate and mucus production.

Disrupting any of these defense mechanisms makes the lining of the stomach and intestine susceptible to the actions of acid and pepsin, increasing the risk for ulcers.

Causes

In 1982, two Australian scientists identified H. pylori as the main cause of stomach ulcers. They showed that inflammation of the stomach and stomach ulcers result from an infection of the stomach caused by H. pylori bacteria. This discovery was so important that the researchers were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2005. The bacteria appear to trigger ulcers in the following way:

- H. pylori's corkscrew shape enables them to penetrate the mucus layer of the stomach or duodenum so that they can attach themselves to the lining. The surfaces of the cells lining the stomach contain a protein, called decay-accelerating factor, which acts as a receptor for the bacteria.

- H. pylori survive in the highly acidic environment by producing urease, an enzyme that generates ammonia to neutralize the acid.

- H. pylori stimulate the increased release of gastrin. Higher gastrin levels promote increased acid secretion. The increased acid damages the intestinal lining, leading to ulcers in certain individuals.

- H. pylori also alter certain immune factors that allow these bacteria to evade detection by the immune system and cause persistent inflammation -- even without invading the mucus membrane.

Even if ulcers do not develop, H. pylori bacteria are considered to be a major cause of active chronic inflammation in the stomach (gastritis) and the upper part of the small intestine (duodenitis).

H. pylori are also strongly linked to stomach cancer and possibly other non-intestinal problems.

Factors that Trigger Ulcers in H. pylori Carriers. Only around 10 - 15% of people who are infected with H. pylori develop peptic ulcer disease. H. pylori infections, particularly in older people, may not always lead to peptic ulcers. Other factors must also be present to actually trigger ulcers, including:

- Genetic Factors. Some people harbor strains of H. pylori with genes that make the bacteria more dangerous, and increase the risk for ulcers.

- Immune Abnormalities. Certain people have an abnormal intestinal immune response, which allow the bacteria to injure the lining of the intestines.

- Lifestyle Factors. Although lifestyle factors such as chronic stress, drinking coffee, and smoking were long believed to be primary causes of ulcers, it is now thought that they only increase susceptibility to ulcers in some H. pylori carriers.

- Shift Work and Other Causes of Interrupted Sleep. People who work the night shift have a significantly higher incidence of ulcers than day workers. Researchers suspect that frequent interruptions of sleep may weaken the immune system's ability to protect against harmful bacteria.

When H. pylori were first identified as the major cause of peptic ulcers, these bacteria were found in 90% of people with duodenal ulcers and in about 80% of people with gastric ulcers. As more people are being tested and treated for the bacteria, however, the rate of H. pylori- associated ulcers has declined. Currently, H. pylori are found in about 50% of people with peptic ulcer disease.

Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

Long-term use of NSAIDs such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), and naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn) is the second most common cause of ulcers. NSAIDs also increase the risk for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding. The risk of bleeding continues for as long as a patient takes these drugs and may last for about 1 year after stopping.

Short courses of NSAIDs for temporary pain relief should not cause major problems, because the stomach has time to recover and repair any damage that has occurred.

Patients with NSAID-caused ulcers should stop taking these drugs. However, patients who require these medications on a long-term basis can reduce their risk of ulcers by taking drugs in the proton pump inhibitor (PPI) group, such as omeprazole (Prilosec). Famotidine (Pepcid -- an H2 blocker) may provide less effective protection.

Other Causes

Certain drugs other than NSAIDs may aggravate ulcers. These include warfarin (Coumadin) -- an anticoagulant that increases the risk of bleeding, oral corticosteroids, some chemotherapy drugs, spironolactone, and niacin.

Bevacizumab, a drug used to treat colorectal cancer, may increase the risk of GI perforation. Although the benefits of bevacizumab outweigh the risks, GI perforation is very serious. If it occurs, patients must stop taking the drug.

Rarely, certain conditions may cause ulcers in the stomach or intestine, including:

- Alcohol abuse

- Bacterial or viral infections

- Burns

- Physical injury

- Radiation treatments

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome (ZES)

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (ZES) is the least common major cause of peptic ulcer disease. In this condition, tumors in the pancreas and duodenum (called gastrinomas) produce excessive amounts of gastrin, a hormone that stimulates gastric acid secretion. These tumors are usually cancerous, so proper and prompt management of the disease is essential.

An estimated 1 out of every 1 million people per year gets ZES. The incidence is 0.1 - 1% among patients with peptic ulcers. Typically the disease starts in people ages 45 - 50, and men are affected more often than women.

ZES should be suspected in patients with ulcers who are not infected with H. pylori and who have no history of NSAID use. Diarrhea may occur before ulcer symptoms. Ulcers occurring in the second, third, or fourth portions of the duodenum or in the jejunum (the middle section of the small intestine) are signs of ZES. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is more common, and often more severe in patients with ZES. Complications of GERD include ulcers and narrowing (strictures) of the esophagus.

Peptic ulcers associated with ZES are typically persistent and difficult to treat. Treatment consists of removing the tumors and suppressing acid with an intravenous PPI (Protonix). In the past, removing the stomach was the only treatment option.

Symptoms

Dyspepsia. The most common symptoms of peptic ulcer are known collectively as dyspepsia. However, peptic ulcers can occur without dyspepsia or any other gastrointestinal symptoms, especially when they are caused by NSAIDs.

The most common peptic ulcer symptoms are abdominal pain, heartburn, and regurgitation (the sensation of acid backing up into the throat).

Other dyspepsia symptoms include:

- Bloating

- A feeling of fullness

- Hunger and an empty feeling in the stomach, often 1 - 3 hours after a meal

- Belching

Many patients with the above symptoms do not have peptic ulcer disease or any other diagnosed condition. In that case, they have what is called functional dyspepsia.

Older patients are less likely to have symptoms than younger patients. A lack of symptoms may delay diagnosis, which may put older patients at greater risk for severe complications.

Recurrent abdominal pain and other gastrointestinal symptoms are common in children, and it is becoming the norm for pediatricians to screen for H. pylori infection in children with these symptoms. However, researchers have not been able to confirm a link between regular abdominal pain and H. pylori infection in children.

Ulcer Pain. Some symptoms are similar to those of gastric ulcers, although not everyone with these symptoms has an ulcer. The pain of ulcers can be in one place, or it can be all over the abdomen. The pain is described as a burning, gnawing, or aching in the upper abdomen, or as a stabbing pain penetrating through the gut. The symptoms may vary depending on the location of the ulcer:

- Duodenal ulcers often cause a gnawing pain in the upper stomach area several hours after a meal, and patients can often relieve the pain by eating. Many patients also have heartburn.

- Gastric ulcers may cause a dull, aching pain, often right after a meal. Eating does not relieve the pain and may even worsen it. Pain may also occur at night.

Ulcer pain may be particularly confusing or disconcerting when it radiates to the back or to the chest behind the breastbone. In such cases it can be confused with other conditions, such as a heart attack.

Because ulcers can cause hidden bleeding, patients may experience symptoms of anemia, including fatigue and shortness of breath.

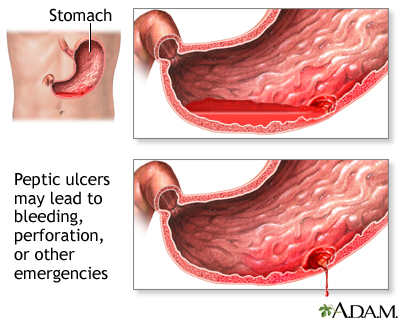

Emergency Symptoms

Severe symptoms that begin suddenly may indicate a blockage in the intestine, perforation, or hemorrhage, all of which are emergencies. Symptoms may include:

- Tarry, black, or bloody stools

- Severe vomiting, which may include blood or a substance with the appearance of coffee grounds (a sign of a serious hemorrhage) or the entire stomach contents (a sign of intestinal obstruction)

- Severe abdominal pain, with or without vomiting or evidence of blood

Anyone who experiences any of these symptoms should go to the emergency room immediately.

Complications

Most people with severe ulcers experience significant pain and sleeplessness, which can have a dramatic and adverse impact on their quality of life.

Peptic ulcers can also have a major effect on a person's finances. Research finds that the complications of peptic ulcer disease can cost from $1,800 to more than $25,000 per patient.

Bleeding and hemorrhage

Peptic ulcers caused by H. pylori or NSAIDs can be very serious if they cause hemorrhage or perforate the stomach or duodenum. Up to 15% of people with ulcers experience some degree of bleeding, which can be life-threatening. Ulcers that form where the small intestine joins the stomach can swell and scar, resulting in a narrowing or closing of the intestinal opening. In such cases, the patient will vomit the entire contents of the stomach, and emergency treatment is necessary.

Complications of peptic ulcers cause an estimated 6,500 deaths each year. These figures, however, do not reflect the high number of deaths associated with NSAID use. Ulcers caused by NSAIDs are more likely to bleed than those caused by H. pylori.

Because there are often no GI symptoms from NSAID ulcers until bleeding begins, doctors cannot predict which patients taking these drugs will develop bleeding. The risk for a poor outcome is highest in people who have had long-term bleeding from NSAIDs, blood clotting disorders, low systolic blood pressure, mental instability, or another serious and unstable medical condition. Populations at greatest risk are the elderly and those with other serious conditions, such as heart problems.

Stomach Cancer and Other Conditions Associated with H. pylori

H. pylori is strongly associated with certain cancers. Some studies have also linked it to a number of non-gastrointestinal illnesses, although the evidence is inconsistent.

Stomach Cancers. Stomach cancer, also called gastric cancer, is the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide. In developing countries, where the rate of H. pylori is very high, the risk of stomach cancer is six times higher than in the U.S. Evidence now suggests that H. pylori may be as carcinogenic (cancer producing) to the stomach as cigarette smoke is to the lungs.

Infection with H. pylori promotes a precancerous condition called atrophic gastritis. The process most likely starts in childhood. It may lead to cancer through the following steps:

- The stomach becomes chronically inflamed and loses patches of glands that secrete protein and acid. (Acid protects against carcinogens, substances that cause cancerous changes in cells.)

- New cells replace destroyed cells, but the new cells do not produce enough acid to protect against carcinogens.

- Over time, cancer cells may develop and multiply in the stomach.

When H. pylori infection starts in adulthood it poses a lower risk for cancer, because it takes years for atrophic gastritis to develop, and an adult is likely to die of other causes first. Other factors, such as specific strains of H. pylori and diet, might also influence the risk for stomach cancer. For example, a diet high in salt and low in fresh fruits and vegetables has been associated with a greater risk. Some evidence suggests that the H. pylori strain that carries the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) may be a particular risk factor for precancerous changes.

Although the evidence is mixed, some research suggests that early elimination of H. pylori may reduce the risk of stomach cancer to that of the general population. It is important to follow patients after treatment for a long period of time.

People with duodenal ulcers caused by H. pylori appear to have a lower risk of stomach cancer, although scientists do not know why. It may be that different H. pylori strains affect the duodenum and the stomach. Or, the high levels of acid found in the duodenum may help prevent the spread of the bacteria to critical areas of the stomach.

Other Diseases. H. pylori also is weakly associated with other non-intestinal disorders, including migraine headache, Raynaud's disease (which causes cold hands and feet), and skin disorders such as chronic hives.

Men with gastric ulcers may face a higher risk for pancreatic cancer, although duodenal ulcers do not seem to pose the same risk.

Risk Factors

About 10% of people in the U.S. are expected to develop peptic ulcers at some point in their lives. Peptic ulcer disease affects all age groups, but it is rare in children. Men have twice the risk of ulcers as women. The risk of duodenal ulcers tends to rise starting at age 25, and continuing until age 75. The risk peaks between ages 55 and 65.

Peptic ulcers are less common than they once were. Research suggests that ulcer rates have even declined in areas where there is widespread H. pylori infection. The increased use of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) drugs may be responsible for this trend. Treatments have also led to a reduction in the rate of H. pylori complications that require a hospital stay. The hospitalization rate for peptic ulcer disease dropped 21% between 1998 and 2005, and hospital stays for H. pylori infection dropped 47% during that same time period.

Risk Factors for H. pylori

H. pylori bacteria are most likely transmitted directly from person to person. Yet little is known about exactly how these bacteria are transmitted.

About 50% of the world's population is infected with H. pylori. The bacteria are nearly always acquired during childhood and persist throughout life if not treated. The prevalence in children is around 0.5% in industrialized nations, where rates continue to decline. Even in industrialized countries, however, infection rates in regions with crowded, unsanitary conditions are equal to those in developing countries.

It is not entirely clear how the bacteria are transmitted. Suggested, but not clearly proven, methods of transmission include:

- Intimate contact, including contact with fluids from the mouth

- GI tract illness (particularly when vomiting occurs)

- Contact with stool (fecal material)

- Sewage-contaminated water

Although H. pylori infection is common, ulcers in children are very rare, and only 5 - 10% of H. pylori-infected adults develop ulcers. Some factors that may explain why certain infected patients get ulcers include:

- Smoking

- Using alcohol

- Having a relative with peptic ulcers

- Being male

- Being infected with a bacterial strain that contains the cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA)

Experts do not know what factor or factors actually increase the risk of developing an ulcer.

Risk Factors for NSAID-Induced Ulcers

Between 15 - 25% of patients who have taken NSAIDs regularly will have evidence of one or more ulcers, but in most cases these ulcers are very small. Given the widespread use of NSAIDs, however, the potential number of people who can develop serious problems may be very large. Long-term NSAID use can damage the stomach and, possibly, the small intestine.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has asked manufacturers of prescription NSAIDs and the COX-2 inhibitor celecoxib (Celebrex) to include with their products a boxed warning emphasizing the increased risk for cardiovascular events and GI bleeding in people taking these drugs.

The FDA also requested that manufacturers of over-the-counter NSAIDs revise their labels to include more specific language concerning potential cardiovascular and GI risks. Due to its proven heart benefits, aspirin was excluded from these labeling revisions.

Frequent Users

NSAIDs. Anyone who uses NSAIDs regularly is at risk for gastrointestinal problems. Even low-dose aspirin (81 mg) may pose some risk, although the risk is lower than with higher doses. The highest risk is among people who use very high-dose NSAIDs over a long period of time, especially patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Other people who take high doses of NSAIDs include those with chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, and chronic headaches.

Compared to NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors may pose less risk for uncomplicated ulcers, but these medications do not seem to reduce the risk of more serious events, such as bleeding or perforation.

Contributing Factors. Certain factors may increase the risk for ulcers in NSAID users:

- Being age 65 or older

- Having a history of peptic ulcers or upper gastrointestinal bleeding

- Having other serious ailments, such as congestive heart failure

- Using other medications, such as the anticoagulant warfarin (Coumadin), corticosteroids, or the osteoporosis drug alendronate (Fosamax)

- Abusing alcohol

- Being infected with H. pylori

Other Risk Factors for Ulcers from H. pylori or NSAIDs

Stress and Psychological Factors. Although stress is no longer considered a cause of ulcers, some studies still suggest that stress may predispose a person to ulcers or prevent existing ulcers from healing.

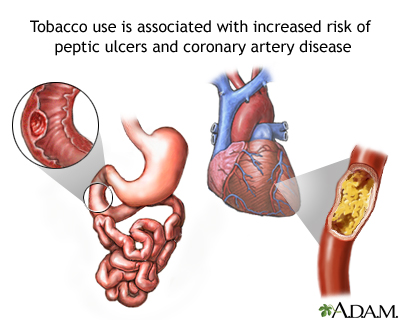

Smoking. Smoking increases acid secretion, reduces prostaglandin and bicarbonate production, and decreases blood flow. However, the results of studies on the actual effect of smoking on ulcers are mixed. Some evidence suggests that smoking delays the healing of gastric and duodenal ulcers. Other studies have found no increased risk for ulcers in smokers.

Diagnosis

Peptic ulcers are always suspected in patients with persistent dyspepsia (bloating, belching, and abdominal pain). Symptoms of dyspepsia occur in 20 - 25% of people who live in industrialized nations, but only about 15 - 25% of those with dyspepsia actually have ulcers. It takes several steps to accurately diagnose ulcers.

Medical and Family History

The doctor will ask for a thorough report of a patient's dyspepsia, as well as:

- Other important symptoms, such as weight loss or fatigue

- Present and past medication use (especially long-term NSAID use)

- Family members with ulcers

- Drinking and smoking habits

Ruling out Other Disorders

Many other conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and irritable bowel syndrome, cause dyspepsia.

Peptic ulcer symptoms, particularly abdominal pain and chest pain, may resemble the symptoms of other conditions, including:

- GERD. About half of patients with GERD also have dyspepsia. With GERD or other problems in the esophagus, the main symptom is usually heartburn, a burning pain that radiates up to the throat. It typically develops after meals and is relieved by antacids. The patient may have difficulty swallowing and may experience regurgitation or acid reflux. Elderly patients with GERD are less likely to have these symptoms, but instead may have appetite loss, weight loss, anemia, vomiting, or dysphagia (difficult or painful swallowing).

- Heart Problems. Heart pain, such as from angina or a heart attack, is more likely to occur with exercise and may radiate to the neck, jaw, or arms. In addition, patients typically have distinct risk factors for heart disease, such as a family history, smoking, high blood pressure, obesity, or high cholesterol.

- Gallstones. The primary symptom in gallstones is a steady gripping or gnawing pain on the right side under the rib cage, which can be severe and can radiate to the upper back. Some patients experience pain behind the breastbone. The pain often occurs after a fatty or heavy meal, but gallstones almost never cause dyspepsia.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Irritable bowel syndrome can cause dyspepsia, nausea and vomiting, bloating, and abdominal pain. It occurs more often in women than in men.

Dyspepsia may also occur with gastritis, stomach cancer, or as a side effect of certain drugs, including NSAIDs, antibiotics, iron, corticosteroids, theophylline, and calcium blockers.

Noninvasive Tests for Gastrointestinal (GI) Bleeding

When ulcers are suspected, the doctor will order tests to detect bleeding. These may include a rectal exam, complete blood count, and fecal occult blood test (FOBT). The FOBT tests for hidden (occult) blood in stools. Typically, the patient is asked to supply up to six stool specimens in a specially prepared package. A small quantity of feces is smeared on treated paper, which is then exposed to hydrogen peroxide. If blood is present, the paper turns blue.

Tests to Detect H. pylori

Simple blood, breath, and stool tests can detect H. pylori with a fairly high degree of accuracy.

Experts recommend testing for H. pylori in all patients with peptic ulcer disease, because it is such a common cause of this condition.

Smokers and those who experience regular and persistent pain on an empty stomach may also be good candidates for screening tests.

Some doctors argue that testing for H. pylori may be beneficial for patients with dyspepsia who are regular NSAID users. Given the possible risk for stomach cancer in H. pylori- infected people with dyspepsia, some experts now recommend that any patient with dyspepsia lasting longer than 4 weeks should have a blood test for H. pylori. This is a subject of considerable debate, however.

Tests for Diagnosing H. pylori. The following tests are used to diagnose H. pylori infection. Testing may also be done after treatment to ensure that the bacteria have been completely eliminated.

- Breath Test. A simple test called the carbon isotope-urea breath test (UBT) can identify up to 99% of people who have H. pylori. Up to 2 weeks before the test, the patient must stop taking any antibiotics, bismuth-containing medications such as Pepto-Bismol, and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). As part of the test, the patient swallows a special substance containing urea (a waste product the body produces as it breaks down protein) that has been treated with carbon atoms. If H. pylori are present, the bacteria convert the urea into carbon dioxide, which is detected and recorded in the patient's exhaled breath after 10 minutes. This test can also be used to confirm that H. pylori have been fully treated.

- Blood Tests. Blood tests are used to measure antibodies to H. pylori, and the results are available in minutes. Diagnostic accuracy is reported to be 80 - 90%. One such important test is called enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). An ELISA test of the urine is also showing promise for diagnosing H. pylori in children.

- Stool Test. A test to detect the genetic traces of H. pylori in the feces appears to be as accurate as the breath test for initially detecting the bacteria, and for detecting recurrences after antibiotic therapy. This test can also be used to confirm that the H. pylori infection has been fully treated.

- The most accurate way to identify the presence of H. pylori is by taking a tissue biopsy from the lining of the stomach. The only way to do this is with endoscopy, which is an invasive procedure. However, many patients are treated for H. pylori based on the three noninvasive tests listed above.

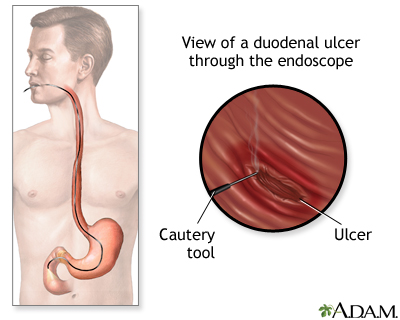

Endoscopy

Endoscopy (also called esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD) is a procedure used to evaluate the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum using an endoscope -- a long, thin tube equipped with a tiny video camera. When combined with a biopsy, endoscopy is the most accurate procedure for detecting the presence of peptic ulcers, bleeding, and stomach cancer, or for confirming the presence of H. pylori.

Appropriate Candidates for Endoscopy. Because endoscopy is invasive and expensive, it is unsuitable for screening everyone with dyspepsia. Endoscopy is usually reserved for patients with dyspepsia who also have risk factors for ulcers, stomach cancer, or both.

Endoscopy is recommended for:

- Patients over age 50 who have new dyspepsia symptoms

- Patients of any age who have "alarm" symptoms (unexplained weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, vomiting, difficulty swallowing, or anemia)

Patients under age 50 who don't have alarm symptoms may be tested non-invasively for H. pylori and treated for the infection if they test positive.

The decision about whether endoscopy should be performed on patients who do not respond to initial medication should be individualized. Endoscopy may be recommended for patients with gastric ulcers who continue to have symptoms despite treatment, or for those who have ulcers without a clear cause. It should also be done before surgery is considered.

The Procedure. Endoscopy may be performed in a hospital, doctor's office, or outpatient surgery center, and typically involves the following:

- The doctor administers a local anesthetic using an oral spray and an intravenous sedative to suppress the gag reflex and relax the patient.

- The doctor then places a thin, flexible plastic tube into the patient's mouth and maneuvers it down the esophagus into the stomach.

- A tiny camera in the endoscope allows the doctor to see the surface of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum, and search for abnormalities.

- The doctor will remove about 10 small tissue samples (biopsies), which will be tested for H. pylori.

Upper GI Series

An upper GI series was the standard method for diagnosing peptic ulcers until endoscopy and tests for detecting H. pylori were introduced. In an upper GI series, the patient drinks a solution containing barium. X-rays are then taken, which may reveal inflammation, active ulcers, or deformities and scarring due to previous ulcers. Endoscopy is more accurate than an upper GI series, although it is also more invasive and expensive.

Other Laboratory Tests

Stool tests may show traces of blood that are not visible to the naked eye, and blood tests may reveal anemia in those who have bleeding ulcers. If Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is suspected, blood levels of gastrin should be measured.

Treatment

Deciding which treatment is best for patients with symptoms of dyspepsia or peptic ulcer disease depends on a number of factors.

An endoscopy to identify any ulcers and test for H. pylori probably gives the best guidance for treatment. However, dyspepsia is such a common reason for a doctor's visit that many people are treated initially based on their symptoms and blood or breath H. pylori test results. This approach (called test and treat) is considered an appropriate option for most patients. Patients who have evidence of bleeding or other alarm symptoms, or who are over age 50 should have an endoscopy performed first.

Approach to Patients Who Are Not Taking NSAIDs

If an endoscopy is performed soon after the patient first visits a doctor for symptoms, treatment is based on the results of the endoscopy:

- If an ulcer is seen and the patient is infected with H. pylori, treatment for the infection is started, followed by 4 - 8 weeks of treatment with a proton pump inhibitor (PPI). Most patients will improve with this treatment.

- If an ulcer is seen but H. pylori are not present, patients are usually treated with PPIs for 8 weeks.

- If no ulcer is seen and the patient is not infected with H. pylori, the first treatment attempt will usually be with PPIs. These patients do not need antibiotics to treat H. pylori. Other possible causes of their symptoms should also be considered.

Most patients who do not have risk factors for complications are treated without first having an endoscopy. The type of treatment is decided based on a patient's symptoms, and on the results of H. pylori blood or breath tests.

Patients who are not infected with H. pylori are given a diagnosis of functional (non-ulcer) dyspepsia. These patients are most commonly given 4 - 8 weeks of a PPI. If this dose is not effective, doubling the dose will occasionally relieve symptoms. If there is still no symptom relief, patients may have an endoscopy. However, it is unlikely that an ulcer is present. In this group of patients, symptoms may not fully improve.

- Patients who test positive for H. pylori infection will receive antibiotics to treat H. pylori. Those who have an ulcer are more likely to respond to antibiotic treatment. Because an endoscopy is not done before treatment in the test and treat strategy, patients who do not have an ulcer are also treated with antibiotics. Even if they test positive for H. pylori, patients who do not have an actual ulcer are less likely to have a full response to antibiotics.

- When the test and treat approach is used, patients who do not respond to treatment, or whose symptoms return relatively quickly will often need an endoscopy.

There is considerable debate about whether to test for H. pylori and treat infected patients who have dyspepsia but no clear evidence of ulcers, in part because H. pylori in the intestinal tract protects against GERD and possibly other conditions. There is also concern about the overuse of antibiotics, which can contribute to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

Antibiotic and Combination Drug Regimens for the Treatment of H. pylori

Reported cure rates for H. pylori range from 70 - 90% after antibiotic treatment. The standard treatment regimen uses two antibiotics and a PPI:

- PPIs. These drugs include omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), esomeprazole (Nexium), and rabeprazole (Aciphex). PPIs are important for all types of peptic ulcers, and are a critical partner in antibiotic regimens. They reduce acidity in the intestinal tract, and increase the ability of antibiotics to destroy H. pylori.

- Antibiotics. The standard antibiotics are clarithromycin (Biaxin) and amoxicillin. The antibiotic metronidazole (Flagyl, generic) may be used instead of amoxicillin in patients who are allergic to penicillin. Tetracycline is sometimes recommended in place of a standard antibiotic.

- Bismuth may be recommended along with antibiotics (see below).

Patients typically take combination treatment for at least 14 days. A 7-day regimen is another option, but some research suggests that 14 days of therapy with antibiotics and PPIs is more effective at eradicating H. pylori.

Follow-Up. Follow-up testing to check that the bacteria have been eliminated should be done no sooner than 4 weeks after therapy is completed. Test results before that time may not be accurate.

In most cases, drug treatment relieves ulcer symptoms. However, symptom relief does not always indicate treatment success, just as persistent dyspepsia does not necessarily mean that treatment has failed. Heartburn and other GERD symptoms can get worse and require acid-suppressing medication.

Failure. Treatment fails in about 10 - 20% of patients, typically when they do not follow their prescribed treatment. Compliance with standard antibiotic regimens may be poor for the following reasons:

- Three drug regimens are complicated, expensive, and require many pills. Simpler regimens are under study.

- About 30% of patients experience side effects from the antibiotic regimen. Gastrointestinal problems are very common, and severe diarrhea can occur.

Treatment may also fail if patients harbor strains of H. pylori that are resistant to antibiotics. When this happens, different drugs are tried.

Re-infection after Successful Treatment. Studies in developed countries indicate that once the bacteria are eliminated, recurrence rates are below 1% per year. Re-infection with the bacteria is possible, however, in areas where the incidence of H. pylori is very high and sanitary conditions are poor. In such regions, re-infection rates are 6 - 15%.

Treatment of NSAID-induced ulcers

If patients are diagnosed with NSAID-caused ulcers or bleeding, they should:

- Get tested for H. pylori and, if they are infected, take antibiotics.

- Possibly use a PPI. Studies suggest that these medications lower the risk for NSAID-caused ulcers, although they do not completely prevent them.

Healing Existing Ulcers. A number of drugs are used to treat NSAID-caused ulcers. PPIs -- omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), or esomeprazole (Nexium) -- are used most often. Other drugs that may be useful include H2 blockers, such as famotidine (Pepcid AC), cimetidine (Tagamet), and ranitidine (Zantac). Sucralfate is another drug used to heal ulcers and reduce the stomach upset caused by NSAIDs.

People with chronic pain may try a number of other medications to minimize the risk of ulcers associated with NSAIDs:

- COX-2 Inhibitors (Coxibs). Coxibs block an inflammation-promoting enzyme called COX-2. This drug class may work as well as NSAIDs and cause less gastrointestinal distress. However, following numerous reports of cardiovascular events with COX-2 inhibitors, only Celecoxib (Celebrex) is still available, and it must be used with great care. (Regular NSAIDs also increase the risk of cardiovascular events.)

- Arthrotec. Arthrotec is a combination of misoprostol and the NSAID diclofenac. It may reduce the risk for gastrointestinal bleeding. This drug can cause miscarriage at any stage of pregnancy and therefore should not be used during pregnancy.

- Acetaminophen. Acetaminophen (Tylenol, Anacin-3) is the most common alternative to NSAIDs. It is inexpensive and generally safe. Acetaminophen poses far less of a gastrointestinal risk than NSAIDs. However, patients who take high doses of acetaminophen for long periods of time are at risk for liver damage, particularly if they drink alcohol. Acetaminophen also may pose a small risk for serious kidney complications in people who already have kidney disease, although it remains the drug of choice for patients with impaired kidney function. Until recently, the recommended maximum daily dose of acetaminophen was 4 grams (4,000 mg), but an FDA advisory panel has recommended lowering the maximum daily dose.

- Tramadol. Tramadol (Ultram) is a pain reliever that has been used as an alternative to opioids. It has opioid-like properties, but is not as addictive. A combination of tramadol and acetaminophen (Ultracet) provides more rapid pain relief than tramadol alone, and more long-term relief than acetaminophen alone. Side effects of tramadol include dependence and abuse, nausea, and itching, but tramadol does not cause the same severe gastrointestinal problems as NSAIDs.

- If patients need to continue taking NSAIDs, they should use the lowest possible dose.

The American College of Gastroenterology has made recommendations about the prevention of ulcers in patients using NSAIDs. Doctors should consider whether their patients are at high, moderate, or low risk for gastrointestinal and cardiovascular problems. Depending on a patient's risk factors, the doctor may recommend any NSAID, naproxen only, a COX-2 inhibitor, one of these, or none of the three.

Some patients take either a PPI or misoprostol along with their NSAID. Before starting a patient on long-term NSAID therapy, the physician should consider testing for H. pylori.

Medications

The following drugs are sometimes used to treat peptic ulcers caused by either NSAIDs or H. pylori.

Antacids

Many antacids are available without a prescription, and they are the first drugs recommended to relieve heartburn and mild dyspepsia. Antacids are not effective for preventing or healing ulcers, but they can help in the following ways:

- They neutralize stomach acid with various combinations of three basic compounds -- magnesium, calcium, or aluminum.

- They may protect the stomach by increasing bicarbonate and mucus secretion.

Liquid antacids are thought to work faster and more effectively than tablets, although some evidence suggests that both forms work equally well.

Basic Salts Used in Antacids. There are three basic salts used in antacids:

- Magnesium. Magnesium compounds are available in the form of magnesium carbonate, magnesium trisilicate, and, most commonly, magnesium hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia). The major side effect of these magnesium compounds is diarrhea.

- Calcium. Calcium carbonate (Tums, Titralac, and Alka-2) is a potent and rapid-acting antacid, but it can cause constipation. There have been rare cases of hypercalcemia (elevated levels of calcium in the blood) in people taking calcium carbonate for long periods of time. Hypercalcemia can lead to kidney failure.

- Aluminum. The most common side effect of antacids containing aluminum compounds (Amphogel, Alternagel) is constipation. Maalox and Mylanta are combinations of aluminum and magnesium, which balance the side effects of diarrhea and constipation. People who take large amounts of antacids containing aluminum may be at risk for calcium loss and osteoporosis. Long-term use also increases the risk of kidney stones. People who have recently experienced GI bleeding should not use aluminum compounds.

Interactions with Other Drugs. Antacids can reduce the absorption of a number of drugs. Conversely, some antacids increase the potency of certain drugs. The interactions can be avoided by taking other drugs 1 hour before or 3 hours after taking the antacid.

Drug Interactions with Antacids (such as Maalox, Mylanta) | |

Drugs that are not absorbed as well if taken with antacids | Drugs that are made more potent by antacids |

Tetracycline Ciprofloxacin (Cipro) Propranolol (Inderal) Captopril (Capoten) Ranitidine (Zantac) Famotidine (Pepcid AC) | Valproic acid Sulfonylureas Quinidine Levodopa |

Antibiotics

H. pylori may be treated with the following antibiotics:

- Amoxicillin is a form of penicillin. It is very effective against H. pylori and is inexpensive, but some people are allergic to it.

- Clarithromycin (Biaxin) is part of the macrolide class of antibiotics. It is the most expensive antibiotic used against H. pylori. It is very effective, but there is growing bacterial resistance to this drug. Resistance rates tend to be higher in women and increase with age. Researchers fear that resistance will increase as more people use the drug.

- Tetracycline is effective, but this medicine has unique side effects, including tooth discoloration in children. Pregnant women cannot take tetracycline.

- Ciprofloxacin (Cipro, generic) or levofloxacin (Levaquin), fluoroquinolone, is also sometimes used in H. pylori regimens.

- Metronidazole (Flagyl, generic) was the mainstay in initial combination regimens for H. pylori. As with clarithromycin, however, there continues to be growing bacterial resistance to the drug.

Side Effects of Antibiotics.

- The most common side effects of nearly all antibiotics are gastrointestinal problems such as cramps, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

- Allergic reactions can also occur with all antibiotics, but are most common with medications derived from penicillin or sulfa. These reactions can range from mild skin rashes to rare, but severe and even life-threatening anaphylactic shock.

- Some drugs, including certain over-the-counter medications, interact with antibiotics. Patients should report all medications they are taking to their doctor.

- Antibiotics double the risk of vaginal yeast infections.

Bismuth

Compounds that contain bismuth destroy the cell walls of H. pylori bacteria. The most common bismuth compound

available in the U.S. has been bismuth subsalicylate (Pepto-Bismol). High doses of bismuth can cause vomiting and depression of the central nervous system, but the doses given for ulcer patients rarely cause side effects.

Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs)

Actions against ulcers. PPIs are the drugs of choice for managing patients with peptic ulcers, regardless of the cause. They suppress the production of stomach acid by blocking the gastric acid pump -- the molecule in the stomach glands that is responsible for acid secretion.

PPIs can be used either as part of a multidrug regimen for H. pylori, or alone for preventing and healing NSAID-caused ulcers. They are also useful for treating ulcers caused by Zollinger-Ellison syndrome. They are considered to be more effective than H2 blockers.

Some people carry a gene that reduces the effectiveness of PPIs. This gene is present in 18 - 20% of people who are of Asian descent.

Standard Brands. Most PPIs are available by prescription as oral drugs. There is no evidence that one brand of PPI works better than another. Brands approved for ulcer prevention and treatment include:

- Omeprazole (generic, Prilosec OTC)

- Esomeprazole (Nexium)

- Lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- Rabeprazole (Aciphex)

Possible Adverse Effects.

- Side effects of PPIs are uncommon, but may include headache, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and itching.

- Pregnant women and nursing mothers should avoid taking PPIs. Although recent studies suggest that these drugs do not increase the risk of birth defects, their safety during pregnancy is not yet proven.

- PPIs may interact with certain drugs, including antiseizure medications (such as phenytoin), anti-anxiety drugs (such as diazepam), and blood thinners (such as warfarin and clopidogrel). Always talk to your doctor before stopping any of these medications.

- Certain PPIs taken with methotrexate, a drug commonly used to treat certain cancers and autoimmune conditions, can lead to elevated levels of methotrexate in the blood, causing toxic side effects.

- Long-term use of high-dose PPIs may cause vitamin B12 deficiency, but more studies are needed to confirm this risk.

In theory, long-term use of PPIs by people with H. pylori may reduce acid secretion enough to cause atrophic gastritis (chronic inflammation of the stomach), a risk factor for stomach cancer. Long-term use of PPIs may also mask the symptoms of stomach cancer and delay diagnosis. At this time, however, there have been no reports of an increase in the incidence of stomach cancer with long-term use of these drugs.

H2 Blockers

H2 blockers interfere with acid production by blocking histamine, a substance produced by the body that encourages acid secretion in the stomach. H2 blockers were the standard treatment for peptic ulcers until PPIs and antibiotic regimens against H. pylori were developed. H2 blockers cannot cure ulcers, but they are useful in certain cases. They are effective only for duodenal ulcers, however.

Four H2 blockers are currently available over-the-counter in the U.S.:

- Famotidine (Pepcid AC)

- Cimetidine (Tagamet)

- Ranitidine (Zantac)

- Nizatidine (Axid)

All four drugs have good safety profiles and few side effects. There are some differences between these drugs:

- Famotidine (Pepcid AC) is the most potent H2 blocker. The most common side effect is headache, which occurs in 4.7% of people who take it. Famotidine is virtually free from drug interactions, but it may have significant adverse effects in patients with kidney problems.

- Cimetidine (Tagamet) has few side effects. However, about 1% of people taking it experience mild temporary diarrhea, dizziness, rash, or headache. Cimetidine interacts with a number of commonly used medications, including phenytoin, theophylline, and warfarin. Long-term use of excessive doses (more than 3 grams a day) may cause erectile dysfunction or breast enlargement in men. These problems go away after the drug is stopped.

- Ranitidine (Zantac) interacts with very few drugs. Ranitidine may provide more pain relief and heal ulcers more quickly than cimetidine in people younger than age 60, but there doesn't seem to be a difference in older patients. A common side effect of ranitidine is headache, which occurs in about 3% of people who take it.

- Nizatidine (Axid) has virtually no side effects and drug interactions.

PPIs are more effective than H2 blockers at healing ulcers in people who take NSAIDs. Treatment effectiveness for PPIs is between 65% and 100%, versus 50% and 85% for H2 blockers, depending on which drugs are used.

Long-Term Concerns. In most cases, H2 blockers have good safety profiles and few side effects. Because H2 blockers can interact with other drugs, be sure to tell your doctor about any other medications you are taking. There are also some concerns about possible long-term effects -- for example, that long-term acid suppression with these drugs may cause cancerous changes in the stomach in patients who also have untreated H. pylori infection. More research is needed to prove this risk.

However, the following concerns are well documented:

- Liver damage. This is more likely with ranitidine than with the other H2 blockers, but it is rare with any of these drugs.

- Kidney-related central nervous system complications. Famotidine is removed by the body primarily by the kidney. This can pose a danger in people with kidney problems. Use of the drug in people with impaired kidney function can affect the central nervous system and may result in anxiety, depression, insomnia or drowsiness, and mental disturbances. As a result, people with kidney failure should reduce the dose and increase the time between doses.

- Increased risk for pneumonia in hospitalized patients, as well as in the community.

- Ulcer perforation and bleeding. Some experts are concerned that the use of acid-blocking drugs may increase the risk for serious complications by masking ulcer symptoms.

Misoprostol

Misoprostol (Cytotec) increases prostaglandin levels in the stomach lining, which protects against the major gastrointestinal side effects of NSAIDs.

Actions against ulcers. Misoprostol can reduce the risk of NSAID-induced ulcers in the upper small intestine by two-thirds, and in the stomach by three-fourths. It does not neutralize or reduce acid, so although the drug is helpful for preventing NSAID-induced ulcers, it is not useful for healing existing ulcers.

Side Effects.

- Because misoprostol can induce miscarriage or cause birth defects, pregnant women should not take it. If pregnancy occurs during treatment, the drug should be stopped at once and the doctor contacted immediately.

- Diarrhea and other gastrointestinal problems are severe enough to cause 20% of patients to stop taking the drug. Taking misoprostol after meals should minimize these effects. One study indicated that taking the drug two to three times a day, instead of the standard regimen of four times, may prove to be just as effective and cause fewer side effects.

Sucralfate

Sucralfate (Carafate) seems to work by adhering to the ulcer and protecting it from further damage by stomach acid and pepsin. It also promotes the defensive processes of the stomach. Sucralfate has an ulcer-healing rate similar to that of H2 blockers. Other than constipation, which occurs in 2.2% of patients, the drug has few side effects. Sucralfate does interact with a wide variety of drugs, however, including warfarin, phenytoin, and tetracycline.

Surgery

When a patient comes to the hospital with bleeding ulcers, endoscopy is usually performed. This procedure is critical for the diagnosis, determination of treatment options, and treatment of bleeding ulcers.

In high-risk patients or those with evidence of bleeding, options include watchful waiting with medical treatments or surgery. The first critical steps for massive bleeding are to stabilize the patient and support vital functions with fluid replacement and possibly blood transfusions. People on NSAIDs should stop taking these drugs, if possible.

Depending on the intensity of the bleeding, patients can be released from the hospital within a day or kept in the hospital for up to 3 days after endoscopy. Bleeding stops spontaneously in about 70 -80% of patients, but about 30% of patients who come to the hospital for bleeding ulcers need surgery. Endoscopy is the surgical procedure most often used for treating bleeding ulcers and patients at high risk for rebleeding. It is usually combined with medications such as epinephrine and intravenous PPIs.

Between 10 - 20% of patients require more invasive procedures for bleeding, such as major abdominal surgery.

Endoscopy for Treating or Preventing Bleeding Ulcers

Endoscopy is important for both diagnosing and treating bleeding ulcers.

Endoscopy for Diagnosing Bleeding Ulcers and Determining Risk of Rebleeding. With endoscopy, doctors are able to detect the signs of bleeding, such as active spurting or oozing of blood from arteries. Endoscopy can also detect specific features in the ulcers, referred to as stigmata, which indicate a higher or lower risk of rebleeding.

Endoscopy as Treatment. Endoscopy is usually used to treat bleeding from visible vessels that are less than 2 mm in diameter. This approach also appears to be very effective at preventing rebleeding in patients whose ulcers are not bleeding, but who have high-risk features (swollen blood vessels or clots sticking to ulcers).

The following is a typical endoscopic treatment procedure:

- The doctor first places the endoscope into the patient's mouth and down the esophagus into the stomach.

- The doctor passes a probe through an endoscope and applies electricity, heat, or small clips to coagulate the blood and stop the bleeding. This procedure also causes fluid buildup, which helps to compress the blood vessels.

- In high-risk cases, the doctor may inject epinephrine (commonly known as adrenaline) directly into the ulcer to enhance the effects of the heating process. Epinephrine activates the process leading to blood coagulation, narrows the arteries, and enhances blood clotting.

- Intravenous (IV) administration of a PPI (usually omeprazole or pantoprazole) significantly prevents rebleeding. (Oral PPIs are also effective, but studies are needed to compare their effectiveness versus IV PPIs.) A PPI may also be useful for initial bleeding episodes when endoscopy is unsuccessful, inappropriate, or unavailable.

Endoscopy is effective at controlling bleeding in most people who are good candidates for the procedure. If rebleeding occurs, a repeat endoscopy is effective in about 75% of patients. Those who fail to respond will need to have major abdominal surgery. The most serious complication from endoscopy is perforation of the stomach or intestinal wall.

Other Medical Considerations. Certain medications may be needed after endoscopy:

- Patients who harbor the H. pylori bacteria need triple therapy, which includes two antibiotics and a PPI, to eliminate H. pylori immediately after endoscopy.

- Somatostatin (a hormone used to prevent bleeding in cirrhosis) is also useful for reducing persistent peptic ulcer bleeding or the risk of recurrence. Researchers are investigating adding other therapies, such as fibrin glue (a blood clotting factor). To date, no therapy has been proven more effective than current treatments.

Major Abdominal Surgery

Major abdominal surgery for bleeding ulcers is now generally performed only when endoscopy fails or is not appropriate. Certain emergencies may require surgical repair, such as when an ulcer perforates the wall of the stomach or intestine, causing sudden intense pain and life-threatening infection.

Surgical Approaches. The standard major surgical approach (called open surgery) uses a wide abdominal incision and standard surgical instruments. Laparoscopic techniques use small abdominal incisions, through which are inserted miniature cameras and instruments. Laparoscopic techniques are increasingly being used for perforated ulcers, and are thought to be comparable in safety to open surgery. Laparoscopic surgery also, results in less pain after the procedure.

Major Surgical Procedures. There are a number of surgical procedures aimed at providing long-term relief of ulcer complications. These include:

- Vagotomy, in which the vagus nerve is cut to interrupt messages from the brain that stimulate acid secretion in the stomach. This surgery may impair stomach emptying. A recent variation that cuts only parts of the nerve may reduce this complication.

- Antrectomy, in which the lower part of the stomach is removed. This part of the stomach manufactures the hormone responsible for stimulating digestive juices.

- Pyloroplasty, which enlarges the opening into the small intestine so that stomach contents can pass into it more easily.

Antrectomy and pyloroplasty are usually performed with vagotomy.

Lifestyle Changes

In the past, it was common practice to tell people with peptic ulcers to consume small amounts of bland foods frequently throughout the day. Research conducted since that time has shown that a bland diet is not effective at reducing the incidence or recurrence of ulcers, and that eating numerous small meals throughout the day is no more effective than eating three meals a day. Large amounts of food should still be avoided, however, because stretching the stomach can result in painful symptoms.

Fruits and Vegetables. A diet that is rich in fiber may cut the risk of developing ulcers in half and speed the healing of existing ulcers. Fiber found in fruits and vegetables is particularly protective. Vitamin A contained in many of these foods may increase the benefit.

Milk. Milk encourages the production of acid in the stomach, although moderate amounts (2 - 3 cups a day) appear to do no harm. Certain probiotics, which are "good" bacteria added to yogurt and other fermented milk drinks, may protect the gastrointestinal system.

Coffee and Carbonated Beverages. Coffee (both caffeinated and decaffeinated), soft drinks, and fruit juices with citric acid increase stomach acid production. Although no studies have proven that any of these drinks contribute to ulcers, consuming more than 3 cups of coffee per day may increase susceptibility to H. pylori infection.

Spices and Peppers. Studies conducted on spices and peppers have yielded conflicting results. The rule of thumb is to use these substances moderately, and to avoid them if they irritate the stomach.

Garlic. Some studies suggest that large amounts of garlic may have some protective properties against stomach cancer, although one study concluded that garlic offered no benefits against H. pylori and, in large amounts, can cause considerable GI distress.

Olive Oil. Studies from Spain have shown that phenolic compounds in virgin olive oil may be effective against eight strains of H. pylori, three of which are antibiotic-resistant.

Vitamins. Although no vitamins have been shown to protect against ulcers, H. pylori appear to impair the absorption of vitamin C, which may play a role in the higher risk of stomach cancer.

Exercise

Some evidence suggests that exercise may help reduce the risk for ulcers in some people.

Resources

- http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov -- National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

- www.gastro.org -- American Gastroenterological Association

- www.acg.gi.org -- American College of Gastroenterology

References

Bao Y. History of peptic ulcer disease and pancreatic cancer risk in men. Gastroenterology. 2010. 138(2):541-549.

Barkun A, Leontiadis G. Systematic review of the symptom burden, quality of life impairment and costs associated with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Med. 2010;123(4):358-366.e2.

Banerjee S, Cash BD, Dominitz JA, Baron TH, Anderson MA, Ben-Menachem T, et al. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. The role of endoscopy in the management of patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(4):663-668.

Chan FK. Celecoxib versus omeprazle and diclofenac in patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis (CONDOR): a randomized trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9736):173-179.

Feinstein LB, Holman RC, Christensen KLY, Steiner CA, Swerdlow DL. Trends in hospitalizations for peptic ulcer disease, United States, 1998 - 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010; 16(9):1410-1418.

Lanza FL, Chan FK, Quigley EM. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for prevention of NSAID-related ulcer complications. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(3):728-738.

Malfertheiner P, Chan FKL, McColl KEL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2009;374(9699):1449-1461.

McColl KEL. Helicobacter pylori infection. NEJM. 2010;362(17):1597-1604.

Spee LA. Association between Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal symptoms in children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):e651-e669.

Vakil N. Peptic Ulcer Disease. in: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ. (eds.) Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, Elsevier, 2010. Ch. 52.

Wu CY, Kuo KN, Wu MS, Chen YJ, Wang CB, Lin JT. Early Helicobacter pylori eradication decreases risk of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1641-1648.

|

Review Date:

10/2/2012 Reviewed By: Reviewed by: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |