Gastroesophageal reflux disease and heartburn

Highlights

Overview

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which gastric contents and acid flow up from the stomach into the esophagus ("food pipe").

- About half of American adults experience GERD at least once a month.

- People of all ages are susceptible to GERD.

- The hallmark symptoms of GERD are:

- Heartburn: a burning sensation in the chest and throat.

- Regurgitation: a sensation of acid backed up in the esophagus.

- Typical symptoms in infants include frequent regurgitation, irritability, arching the back, choking or gagging, and resisting feedings.

Causes

- The band of muscle tissue called the LES is essential for maintaining a pressure barrier against backflow of contents from the stomach. If it weakens and loses tone, the LES cannot close completely, and acid from the stomach backs up into the esophagus.

Risk Factors for GERD

- Obesity contributes to GERD, and it may increase the risk for erosive esophagitis (severe inflammation in the esophagus) in GERD patients.

- Increasing evidence indicates that smoking raises the risk for GERD.

Risk Factors for Barrett’s Esophagus

- Genetic factors may play an especially strong role in susceptibility to Barrett's esophagus, a precancerous condition caused by very severe GERD.

Medication Warnings

- Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) has been linked to an increased risk of hip, wrist, and spine fractures.

- Studies have found that taking PPIs with the blood thinner clopidogrel (Plavix) reduces the effectiveness of this blood thinner by nearly 50%.

- A warning added in May 2012 cautions that using certain PPIs with methotrexate, a drug commonly used to treat certain cancers and autoimmune conditions, can lead to elevated levels of methotrexate in the blood, causing toxic side effects.

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a condition in which acid from the stomach flows back up into the esophagus (the food pipe), a situation called reflux. Reflux occurs if the muscular actions of the lower esophagus or other protective mechanisms fail.

The hallmark symptoms of GERD are:

- Heartburn: a burning sensation in the chest and throat

- Regurgitation: a sensation of acid backed up in the esophagus

Although acid is a primary factor in damage caused by GERD, other products of the digestive tract, including pepsin and bile, can also be harmful.

The Esophagus

The esophagus, commonly called the food pipe, is a narrow muscular tube about nine-and-a-half inches long. It begins below the tongue and ends at the stomach. The esophagus is narrowest at the top and bottom; it also narrows slightly in the middle.

The esophagus consists of three basic layers:

- An outer layer of fibrous tissue

- A middle layer containing smoother muscle

- An inner membrane, which contains many tiny glands

When a person swallows food, the esophagus moves it into the stomach through the action of wave-like muscle contractions, called peristalsis. In the stomach, acid and various enzymes break down the starch, fat, and protein in food. The lining of the stomach has a thin layer of mucus that protects it from these fluids.

If acid and enzymes back up into the esophagus, however, its lining offers only a weak defense against these substances. Instead, several other factors protect the esophagus. The most important structure protecting the esophagus may be the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The LES is a band of muscle around the bottom of the esophagus, where it meets the stomach.

- After a person swallows, the LES opens to let food enter the stomach. It then closes immediately to prevent regurgitation of the stomach contents, including gastric acid.

- The LES maintains this pressure barrier until food is swallowed again.

If the pressure barrier is not enough to prevent regurgitation and acid backs up (reflux), peristaltic action of the esophagus serves as an additional defense mechanism, pushing the backed-up contents back down into the stomach.

Causes

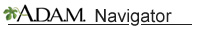

Anyone who eats a lot of acidic foods can have mild and temporary heartburn. This is especially true when lifting, bending over, or lying down after eating a large meal high in fatty, acidic foods. Persistent GERD, however, may be due to various conditions, including biological or structural problems.

Malfunction of the Lower Esophageal Sphincter Muscles

The band of muscle tissue called the LES is responsible for closing and opening the lower end of the esophagus, and is essential for maintaining a pressure barrier against contents from the stomach. For it to function properly, there needs to be interaction between smooth muscles and various hormones. If it weakens and loses tone, the LES cannot close completely after food empties into the stomach, and acid from the stomach backs up into the esophagus. Dietary substances, drugs, and nervous system factors can weaken the LES and impair its function.

Impaired Stomach Function

Patients with GERD have abnormal nerve or muscle function in the stomach. These abnormalities prevent the stomach muscles from contracting normally, which causes delays in stomach emptying, increasing the risk for acid back-up.

Abnormalities in the Esophagus

Some studies suggest that most people with atypical GERD symptoms (such as hoarseness, chronic cough, or the feeling of having a lump in the throat) may have specific abnormalities in the esophagus.

Motility Abnormalities. Problems in spontaneous muscle action (peristalsis) in the esophagus commonly occur in GERD, although it is not clear whether such problems cause the condition, or are the result of long-term GERD.

Adult-Ringed Esophagus. People with this condition have many rings on the esophagus and persistent trouble swallowing (including getting food stuck in the esophagus). Adult-ringed esophagus occurs mostly in men.

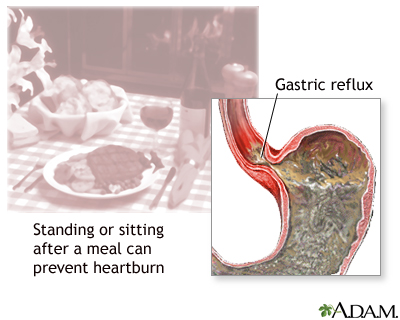

Hiatal Hernia

The hiatus is a small opening in the diaphragm through which the esophagus passes into the stomach. It's normally small and tight, but it may weaken and enlarge. When this happens, part of the stomach muscles may protrude into it, producing a condition called hiatal hernia. It is very common, occurring in more than half of people over 60 years old, and is rarely serious. It was once believed that most cases of persistent heartburn were caused by a hiatal hernia. Indeed, a hiatal hernia may impair LES muscle function. However, studies have failed to confirm that it is a common cause of GERD, although its presence may increase GERD symptoms in patients who have both conditions.

Genetic Factors

About 30 - 40% of reflux may be hereditary. An inherited risk exists in many cases of GERD, possibly because of inherited muscular or structural problems in the stomach or esophagus. Genetic factors may play an especially strong role in susceptibility to Barrett's esophagus, a precancerous condition caused by very severe GERD.

Other Conditions Associated with GERD

Crohn's disease is a chronic ailment that causes inflammation and injury in the small intestine, colon, and other parts of the gastrointestinal tract, sometimes including the esophagus. Other disorders that may contribute to GERD include diabetes, any gastrointestinal disorder (including peptic ulcers), lymphomas, and other types of cancer.

Eradication of Helicobacter Pylori

Helicobacter pylori, also called H. pylori, is a bacterium sometimes found in the mucus membranes of the stomach. It is now known to be a major cause of peptic ulcers. Antibiotics that eradicate H. pylori are an accepted treatment for curing ulcers. Of some concern, however, are studies indicating that H. pylori may actually protect against GERD by reducing

stomach acid. Curing ulcers by eliminating the bacteria might trigger GERD in some people. Studies are mixed, however, on whether curing H. pylori infections increases the risk for GERD.

Still, the bacteria should be eradicated in infected patients with existing GERD who are taking acid suppressing medications. There is some evidence that the combination of H. pylori and chronic acid suppression in these patients can lead to atrophic gastritis, a precancerous condition in the stomach.

Drugs that Increase the Risk for GERD

NSAIDs. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), common causes of peptic ulcers, may also cause GERD or increase its severity in people who already have it. There are dozens of NSAIDs, including over-the-counter aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil, Nuprin), and naproxen (Aleve), as well as prescription anti-inflammatory medicines. People with GERD who take the occasional aspirin or other NSAID will not necessarily experience adverse effects, especially if they have no risk factors or evidence of ulcers. Acetaminophen (Tylenol), which is NOT an NSAID, is a good alternative for those who want to relieve mild pain without increasing GERD risk. Tylenol does not relieve inflammation, however.

Other Drugs. Many other drugs can cause GERD, including:

- Calcium channel blockers (used to treat high blood pressure and angina)

- Anticholinergics (used to treat urinary tract disorders, allergies, and glaucoma)

- Beta adrenergic agonists (used to treat asthma and obstructive lung diseases)

- Dopamine agonists (used in Parkinson's disease)

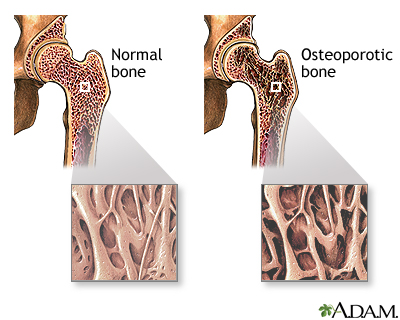

- Bisphosphonates (used to treat osteoporosis)

- Sedatives

- Antibiotics

- Potassium

- Iron pills

Risk Factors

About half of American adults experience GERD at least once a month. People of all ages are susceptible to GERD. Elderly people with GERD tend to have a more serious condition than younger people.

Risk Factors for Heartburn and GERD

Eating Pattern. People who eat a heavy meal and then lie on their back or bend over from the waist are at risk for an attack of heartburn. Anyone who snacks at bedtime is also at high risk for heartburn.

Pregnancy. Pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to GERD in their third trimester, as the growing uterus puts increasing pressure on the stomach. Heartburn in such cases is often resistant to dietary interventions and even to antacids.

Obesity. A number of studies suggest that obesity contributes to GERD, and it may increase the risk for erosive esophagitis (severe inflammation in the esophagus) in GERD patients. Studies indicate that having excess abdominal fat may be the most important risk factor for the development of acid reflux and associated complications, such as Barrett's esophagus and cancer of the esophagus. Researchers have also reported that increased BMI is associated with more severe GERD symptoms. Losing weight appears to help reduce GERD symptoms. However, gastric banding surgery to combat obesity may actually increase the risk for, or worsen symptoms of GERD.

Respiratory Diseases. People with asthma are at very high risk for GERD. Between 50% and 90% of patients with asthma have some symptoms of GERD. People with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are also at increased risk for GERD, and having GERD may worsen pre-existing COPD.

Smoking. Increasing evidence indicates that smoking raises the risk for GERD. Studies suggest that smoking reduces LES muscle function, increases acid secretion, impairs muscle reflexes in the throat, and damages protective mucus membranes. Smoking reduces salivation, and saliva helps neutralize acid. It is unknown whether the smoke, nicotine, or both trigger GERD. Some people who use nicotine patches to quit smoking, for example, have heartburn, but it is not clear whether the nicotine or stress produces the acid backup. In addition, smoking can lead to emphysema, a form of COPD, which is itself a risk factor for GERD.

Alcohol Use. Alcohol has mixed effects on GERD. It relaxes the LES muscles and, in high amounts, may irritate the mucus membrane of the esophagus. Small amounts of alcohol, however, may actually protect the mucosal layer.

It should be noted that a combination of heavy alcohol use and smoking increases the risk for esophageal cancer.

Hormone Replacement Therapy. Symptoms of GERD are more likely to occur in postmenopausal women who receive hormone replacement therapy. The risk increases with larger estrogen doses and longer duration of therapy.

Symptoms

Heartburn. Heartburn is the primary symptom of GERD. It is a burning sensation that spreads up from the stomach to the chest and throat. Heartburn is most likely to occur in connection with the following activities:

- Eating a heavy meal

- Bending over

- Lifting

- Lying down, particularly on the back

Patients with nighttime GERD, a common problem, tend to feel more severe pain than those whose symptoms occur at other times of the day.

The severity of heartburn does not necessarily indicate actual injury to the esophagus. For example, Barrett's esophagus, which causes precancerous changes in the esophagus, may only trigger a few symptoms, especially in elderly people. On the other hand, people can have severe heartburn but suffer no damage in their esophagus.

Dyspepsia. Up to half of GERD patients have dyspepsia, a syndrome that consists of the following:

- Pain and discomfort in the upper abdomen

- A feeling of fullness in the stomach

- Nausea after eating

People without GERD can also have dyspepsia.

Regurgitation. Regurgitation is the feeling of acid backing up in the throat. Sometimes acid regurgitates as far as the mouth and can be experienced as a "wet burp." Uncommonly, it may come out forcefully as vomit.

Less Common Symptoms

Many patients with GERD do not have heartburn or regurgitation. Elderly patients with GERD often have less typical symptoms than do younger people. Instead, symptoms may occur in the mouth or lungs.

Chest Sensations or Pain. Patients may have the sensation that food is trapped behind the breastbone. Chest pain is a common symptom of GERD. It is very important to differentiate it from chest pain caused by heart conditions, such as angina and heart attack.

Symptoms in the Throat. Less commonly, GERD may produce symptoms that occur in the throat:

- Acid laryngitis. A condition that includes hoarseness, dry cough, the sensation of having a lump in the throat, and the need to repeatedly clear the throat.

- Trouble swallowing (dysphagia). In severe cases, patients may choke or food may become trapped in the esophagus, causing severe chest pain. This may indicate a temporary spasm that narrows the tube, or it could indicate serious esophageal damage or abnormalities.

- Chronic sore throat

- Persistent hiccups

Coughing and Respiratory Symptoms. Airway symptoms, such as coughing and wheezing, may occur.

Chronic Nausea and Vomiting. Nausea that persists for weeks or even months, and is not traced back to a common cause of stomach upset, may be a symptom of acid reflux. In rare cases, vomiting can occur as often as once a day. All other causes of chronic nausea and vomiting should be ruled out, including ulcers, stomach cancer, obstruction, and pancreas or gallbladder disorders.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Children

GERD is very common in children of all ages, but it is usually mild. Symptoms usually get better in most infants by age 12 months, and in nearly all children by 24 months. Children with the following conditions are at higher risk for severe GERD:

- Neurological impairments

- Food allergies

- Scoliosis

- Cyclic vomiting

- Cystic fibrosis

- Problems in the lungs, ear, nose, or throat

- Any medical condition affecting the digestive tract

Symptoms in Children. Typical symptoms in infants include frequent regurgitation, irritability, arching the back, choking or gagging, and resisting feedings.

A physician should examine any child who has symptoms of severe GERD as soon as possible, because these symptoms may indicate complications such as anemia, failure to gain weight, or respiratory problems. Symptoms of severe GERD in infants and small children may include:

- Failure to thrive

- Chronic coughing

- Frequent infections

- Wheezing

- Gasping or frequently stopping breathing while asleep (a condition called sleep apnea)

- Severe vomiting -- particularly if it is green colored (bilious) -- always requires a doctor's visit, because it could be a symptom of a severe obstruction.

Babies and children may experience these symptoms without having GERD. Many infants with normal irritability are being inappropriately treated for reflux disorders.

Complications

Nearly everyone has an attack of heartburn at some point in their lives. In the vast majority of cases the condition is temporary and mild, causing only short-term discomfort. If patients develop persistent gastroesophageal reflux disease with frequent relapses, and it remains untreated, serious complications may develop over time. Complications can include:

- Erosive esophagitis

- Severe narrowing (stricture) of the esophagus

- Barrett's esophagus

- Problems in other areas, including the teeth, throat, and airways leading to the lungs

Older people are at higher risk for complications from persistent GERD. The following conditions also put individuals at risk for recurrent and serious GERD:

- Very inflamed esophagus

- Severe symptoms

- Symptoms that continue in spite of treatments to heal the esophagus

- Severe muscle abnormalities

Despite the complications that can occur with the condition, GERD does not appear to shorten life expectancy.

Erosive Esophagitis and its Complications

Erosive esophagitis develops in chronic GERD patients when acid irritation and inflammation cause extensive injuries to the esophagus. The longer and more severe the GERD, the higher the risk for developing erosive esophagitis.

Bleeding. Bleeding may occur in about 8% of patients with erosive esophagitis. In very severe cases, people may have dark-colored, tarry stools (indicating the presence of blood) or may vomit blood, particularly if ulcers have developed in the esophagus. This is a sign of severe damage and requires immediate attention.

Sometimes long-term bleeding can result in iron-deficiency anemia and may even require emergency blood transfusions. This condition can occur without heartburn or other warning symptoms, or even without obvious blood in the stools.

Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Cancer

Barrett's esophagus. Barrett's esophagus (BE) leads to abnormal changes in the cells of the esophagus, which puts a patient at risk for esophageal cancer.

About 10% of patients with symptomatic GERD have BE. In some cases, BE develops as an advanced stage of erosive esophagitis. While obesity, alcohol use, and smoking have all been implicated as risk factors for Barrett's esophagus, their role remains unclear. Only the persistence of GERD symptoms indicates a higher risk for BE.

Not all patients with BE have either esophagitis or symptoms of GERD. In fact, studies suggest that more than half of people with BE have no GERD symptoms at all. BE, then, is likely to be much more prevalent and probably less harmful than is currently believed. (BE that occurs without symptoms can only be identified in clinical trials or in autopsies, so it is difficult to determine the true prevalence of this condition.)

The incidence of esophageal cancer is higher in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Most cases of esophageal cancer start with BE, and symptoms are present in less than half of these cases. Still, only a minority of BE patients develop cancer. When BE patients develop abnormalities of the mucus membrane cells lining the esophagus (dysplasia), the risk of cancer rises significantly. There is some evidence that acid reflux may contribute to the development of cancer in BE.

Complications of Stricture

If the esophagus becomes severely injured over time, narrowed regions called strictures can develop, which may impair swallowing (a condition known as dysphagia). Stretching procedures or surgery may be required to restore normal swallowing. Strictures may actually prevent other GERD symptoms, by stopping acid from traveling up the esophagus.

Asthma and Other Respiratory Disorders

Asthma. Asthma and GERD often occur together. Some theories about the connection between GERD and asthma are:

- Small amounts of stomach acid backing up into the esophagus can lead to changes in the immune system, and these changes trigger asthma.

- Acid leaking from the lower esophagus stimulates the vagus nerves, which run through the gastrointestinal tract. These stimulated nerves cause the nearby airways in the lung to constrict, producing asthma symptoms.

- Acid backup that reaches the mouth may be inhaled (aspirated) into the airways. Here, the acid triggers a reaction in the airways that causes asthma symptoms.

There is some evidence that asthma triggers GERD, but in patients who have both conditions, treating GERD does not appear to improve asthma.

Other Respiratory and Airway Conditions. Studies indicate an association between GERD and various upper respiratory problems that occur in the sinuses, ear and nasal passages, and airways of the lung. People with GERD appear to have an above-average risk for chronic bronchitis, chronic sinusitis, emphysema, pulmonary fibrosis (lung scarring), and recurrent pneumonia. If a person inhales fluid from the esophagus into the lungs, serious pneumonia can occur. It is not yet known whether treating GERD would also reduce the risk for these respiratory conditions.

Dental Problems

Dental erosion (the loss of the tooth's enamel coating) is a very common problem among GERD patients, including children. It results from acid backing up into the mouth and wearing away the tooth enamel.

Chronic Throat Conditions

An estimated 20 - 60% of patients with GERD have symptoms in the throat (hoarseness, sore throat) without any significant heartburn. A failure to diagnose and treat GERD may lead to persistent throat conditions, such as chronic laryngitis, hoarseness, difficulty speaking, sore throat, cough, constant throat clearing, and granulomas (soft, pink bumps) on the vocal cords.

Sleep Apnea

GERD commonly occurs with obstructive sleep apnea, a condition in which breathing stops temporarily many times during sleep. It is not clear which condition is responsible for the other, but GERD is particularly severe when both conditions occur together. Both conditions may also have risk factors in common, such as obesity and sleeping on the back. Studies suggest that in patients with sleep apnea, GERD can be markedly improved with a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device, which opens the airways and is the standard treatment for severe sleep apnea.

Complications in Infants and Children

Feeding Problems. Children with GERD tend to refuse food and may be late in eating solid foods.

Associations with Asthma and Infections in the Upper Airways. In addition to asthma, GERD is associated with other upper airway problems, including ear infections and sinusitis.

Rare Complications in Infants. Although GERD is very common, the following complications only occur in rare cases:

- Failure to thrive

- Anemia resulting from feeding problems and severe vomiting

- Acid backup that is inhaled into the airways and causes pneumonia

The infant's life may be in danger if acid reflux causes spasms in the larynx severe enough to block the airways. Some experts believe this chain of events may contribute to sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). More research is needed to determine whether this association is valid.

Diagnosis

A person with chronic heartburn is likely to have GERD. (Occasional heartburn does not necessarily indicate the presence of GERD.) The following is the general way to diagnose GERD:

- A physician can usually diagnose GERD if the patient finds relief from persistent heartburn and acid regurgitation after taking antacids for short periods of time.

- If the diagnosis is uncertain but the physician still suspects GERD, a drug trial using a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) medication, such as omeprazole (Prilosec, generic), identifies 80% - 90% of people with the condition. This class of medication blocks stomach acid secretion.

Laboratory or more invasive tests, including endoscopy, may be required if:

- The diagnosis is still uncertain

- Symptoms are not typical

- Barrett's esophagus is suspected

- Complications, such as signs of bleeding or difficulty swallowing, are present

Some of these tests are described below.

Barium Swallow Radiograph

A barium swallow radiograph (x-ray) is useful for identifying structural abnormalities and erosive esophagitis. For this test, the patient drinks a solution containing barium, and then x-rays of the digestive tract are taken. This test can show stricture, active ulcer craters, hiatal hernia, erosion, or other abnormalities. However, it cannot reveal mild irritation.

Upper Endoscopy

Upper endoscopy, also called esophagogastroduodenoscopy or panendoscopy, is more accurate than a barium swallow radiograph. It is also more invasive and expensive. It is widely used in GERD for identifying and grading severe esophagitis, monitoring patients with Barrett's esophagus, or when other complications of GERD are suspected. Upper endoscopy is also used as part of various surgical techniques.

Until recently, experts recommended screening with endoscopy for Barrett's esophagus and esophageal cancer at least once in a lifetime for patients with chronic GERD. However, new guidelines from the American Gastroenterological Association do not recommend endoscopy screening because there is no evidence that it can improve survival.

Endoscopy to Diagnose GERD. Endoscopy may be performed either in a hospital or doctor's office:

- The patient should eat nothing for at least 6 hours before the procedure.

- The doctor administers a local anesthetic using an oral spray and an intravenous sedative to suppress the gag reflex and relax the patient.

- Next, the physician places an endoscope (a thin, flexible fiberoptic tube containing a tiny camera) into the patient's mouth and down the esophagus. The procedure does not interfere with breathing. It may be slightly uncomfortable for some patients; others are able to sleep through it.

- Once the endoscope is in place, the camera allows the physician to see the surface of the esophagus and look for abnormalities, including hiatal hernia and damage to the mucus lining.

- The physician performs a biopsy (the removal and microscopic examination of small tissue sections). The biopsy may detect tissue injury from GERD. It may also be used to detect cancer or other conditions, such as yeast (Candida albicans) or viral infections (such as herpes simplex and cytomegalovirus). Such infections are more likely to occur in people with impaired immune systems.

Complications from the procedure are uncommon. If they occur, complications are usually mild and typically include minor bleeding from the biopsy site or irritation where medications were injected.

If a patient has moderate-to-severe GERD symptoms and the procedure reveals injury in the esophagus, usually no further tests are needed to confirm a diagnosis. The test is not foolproof, however. A visual view misses about half of all esophageal abnormalities.

Capsule Endoscopy. In this test, the patient swallows a small capsule containing a tiny camera. Then, a series of color pictures are transmitted to a recording device where they can be downloaded and interpreted by a doctor. The entire procedure takes 20 minutes. The capsule is naturally passed through the digestive system within 24 hours. A newer technique has a string attached to the capsule for retrieval. Capsule endoscopy may provide a more attractive and less invasive alternative to traditional endoscopy. However, while capsule endoscopy is useful as a screening device for diagnosing esophageal conditions such as GERD and Barrett's esophagus, traditional endoscopy is still required for obtaining tissue samples.

Monitoring for Barrett's Esophagus and Cancer

Barrett's esophagus is diagnosed using endoscopy.

Monitoring Patients with Barrett's Esophagus for Cancer. Periodic endoscopy is recommended for detecting cancer at an earlier stage in patients who have been diagnosed with Barrett's esophagus. When Barrett's esophagus is diagnosed, multiple biopsies are generally taken. The biopsy results will determine the frequency of future monitoring. Unfortunately, monitoring patients with Barrett's esophagus has not been proven to change overall mortality rates from esophageal cancer.

pH Monitor Examination

The (ambulatory) pH monitor examination may be used to determine acid backup. It is useful when endoscopy has not detected damage to the mucus lining in the esophagus, but GERD symptoms are present. pH monitoring may be used when patients have not found relief from medicine or surgery. Traditional trans-nasal catheter diagnostic procedures involved inserting a tube through the nose and down to the esophagus. The tube was left in place for 24 hours. This test was irritating to the throat, and uncomfortable and awkward for most patients.

A method known as the Bravo pH test uses a small capsule-sized data transmitter that is temporarily attached to the wall of the esophagus during endoscopy. The capsule records pH levels and transmits these data to a pager-sized receiver the patient wears. Patients can maintain their usual diet and activity schedule during the 24 - 48-hour monitoring period. After a few days, the capsule detaches from the esophagus, passes through the digestive tract, and is eliminated through a bowel movement.

Manometry

Manometry is a technique that measures muscular pressure. It uses a tube containing various openings, which is placed through the esophagus. As the muscular action of the esophagus puts pressure on the tube in various locations, a computer connected to the tube measures this pressure. Manometry is useful for the following situations:

- To determine whether a GERD patient would benefit from surgery, by measuring pressure exerted by the lower esophageal sphincter muscles.

- To detect impaired stomach motility (an inability of the muscles to contract normally) that cannot be surgically corrected with standard procedures.

- To determine whether impaired peristalsis or other motor abnormalities are causing chest pain in people with GERD.

Other Tests

Blood and Stool Tests. Stool tests may show traces of blood that are not visible. Blood tests for anemia should be performed if bleeding is suspected.

Bernstein Test. For patients with chest pain in which the diagnosis is uncertain, a procedure called the Bernstein test may be helpful, although it is rarely used today. A tube is inserted through the patient's nasal passage. Solutions of hydrochloric acid and saline (salt water) are administered separately into the esophagus. A diagnosis of GERD is established if the acid infusion causes symptoms but the saline solution does not.

Ruling out Other Disorders

Because many illnesses share similar symptoms, a careful diagnosis and consideration of the patient's history is key to an accurate diagnosis. The following are only a few of the conditions that could accompany or resemble GERD:

- Dyspepsia. The most common disorder confused with GERD is dyspepsia, which is pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen without heartburn. Specific symptoms may include a feeling of fullness (particularly early in the meal), bloating, and nausea. Dyspepsia can be a symptom of GERD, but it does not always occur with GERD. Treatment with both antacids and proton pump inhibitors can have benefits. The drug metoclopramide (Reglan) helps stomach emptying and may be useful for this condition.

- Angina and Chest Pain. About 600,000 people come to emergency rooms each year with chest pain. More than 100,000 of these people are believed to actually have GERD. Chest pain from both GERD and severe angina can occur after a heavy meal. In general, a heart problem is less likely to be responsible for the pain if it is worse at night and does not occur after exercise- in people who are not known or at risk to have heart disease. It should be noted that the two conditions often coexist.

- Other Diseases. Many gastrointestinal diseases (such as inflammatory bowel disease, ulcers, and intestinal cancers) can cause symptoms similar to GERD, but they can be diagnosed correctly because they produce additional symptoms and affect different areas of the intestinal tract.

Lifestyle Treatment and Prevention

People with heartburn should first try lifestyle and dietary changes. Some suggestions are:

- Avoid or reduce consumption of foods and beverages that contain caffeine, chocolate, garlic, onions, peppermint, spearmint, and alcohol. Both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffees increase acid secretion.

- Avoid all carbonated drinks, because they increase the risk for GERD.

- Choose low-fat or skim dairy products, poultry, and fish

- Eat a diet rich in fruits and vegetables, although it's best to avoid acidic vegetables and fruits (such as oranges, lemons, grapefruit, pineapple, and tomatoes).

- Patients who have trouble swallowing should avoid tough meats, vegetables with skins, doughy bread, and pasta.

Prevention of Nighttime GERD

Nearly three-quarters of patients with frequent GERD symptoms have them at night. Patients with nighttime GERD also tend to experience severe pain. It is very important to take preventive measures before going to sleep, such as:

- After meals, take a walk or stay upright.

- Avoid bedtime snacks. In general, do not eat for at least 2 hours before bedtime.

- When going to bed, try lying on the left side rather than the right side. The stomach is located higher than the esophagus when you sleep on the right side, which can put pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), increasing the risk for fluid backup.

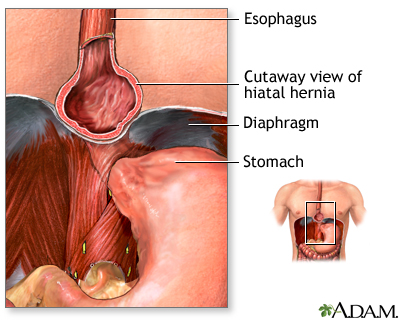

- Sleep in a tilted position to help keep acid in the stomach at night. To do this, raise the bed at an angle using 4- to 6-inch blocks at the head of the bed. Use a wedge-support to elevate the top half of your body. (Extra pillows that only raise the head actually increase the risk for reflux.)

Other Preventive Measures

- Quitting smoking is essential.

- People who are overweight should try to diet and exercise to lose weight.

- People with GERD should avoid wearing tight clothing, particularly around the abdomen.

- If possible, GERD patients should avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil), or naproxen (Aleve). Tylenol (acetaminophen) is a good alternative pain reliever.

Although gum chewing is commonly believed to increase the risk for GERD symptoms, one study reported that it might be helpful. Because saliva helps neutralize acid and contains a number of other factors that protect the esophagus, chewing gum 30 minutes after a meal has been found to help relieve heartburn and even protect against damage caused by GERD. Chewing on anything can help, because it stimulates saliva production.

Treatment

Acid suppression continues to be the mainstay for treating GERD that does not respond to lifestyle changes and treatment. The aim of drug therapy is to reduce the amount of acid and improve any abnormalities in muscle function of the lower esophageal sphincter, esophagus, or stomach.

Most cases of gastroesophageal reflux are mild and can be managed with lifestyle changes, over-the-counter medications, and antacids.

Drug Treatments

Patients with moderate-to-severe symptoms that do not respond to lifestyle changes, or who are diagnosed at a late stage may be started on medications of varying strength, depending on their complications at diagnosis. Experts argue, however, about the best way to start drug treatment for GERD in most of these patients. The two major treatment options are known as the step-up and step-down approaches:

- Step-up. With a step-up drug approach the patient first tries an H2 blocker drug (a drug that interferes with acid production), which is available over the counter. These drugs include famotidine (Pepcid AC, generic), cimetidine (Tagamet HB, generic), ranitidine (Zantac 75, generic ), and nizatidine (Axid AR, generic). If the condition fails to improve, therapy is "stepped up" to the more powerful proton-pump inhibitors (PPI), usually omeprazole (Prilosec, generic).

- Step-down. A step-down approach first uses a more potent drug, most often a PPI, such as omeprazole. When patients have been symptom-free for 2 months or longer, they are then "stepped down" to a half-dose. If symptoms do not come back, the drug is stopped. If symptoms return, the patient is put on high-dose H2 blockers. Some physicians argue that the step-down approach should be used for most patients with moderate-to-severe GERD. If neither approach relieves symptoms, the physician should look for other conditions. Endoscopy and other tests might be used to confirm GERD and rule out other disorders, as well as evaluate when treatment is not working. In some cases, bile, not acid, may be responsible for symptoms, so acid-reducing or blocking agents would not be helpful. (Bile is a fluid that is present in the small intestine and gallbladder.)

Surgery

Surgery may be needed in certain circumstances:

- If lifestyle changes and drug treatments have failed

- If patients cannot tolerate medication

- In patients who have other medical complications

- In younger people with chronic GERD, who face a lifetime of expense and inconvenience with maintenance drug treatment

Some physicians are recommending surgery as the treatment of choice for many more patients with chronic GERD, particularly because minimally invasive surgical procedures are becoming more widely available, and only surgery improves regurgitation. Furthermore, persistent GERD appears to be much more serious than was previously believed, and the long-term safety of using medication for acid suppression is still uncertain.

Nevertheless, anti-GERD procedures have many complications and high failure rates. As with medications, current surgical procedures cannot cure GERD. About 15% of patients still require anti-GERD medications after surgery. Furthermore, about 40% of surgical patients are at risk for new symptoms after surgery (such as gas, bloating, and trouble swallowing), with most side effects occurring more than a year after surgery. Finally, evidence now suggests that surgery does not reduce the risk for esophageal cancer in high-risk patients, such as those with Barrett's esophagus. New procedures may improve current results, but at this time patients should consider surgical options very carefully with both a surgeon and their primary doctor.

Treatments for Barrett's Esophagus

To date, no treatments can reverse the cellular damage after Barrett's esophagus has developed, although some procedures are showing promise.

Medications. If a patient is diagnosed with Barrett's esophagus, the doctor will prescribe PPIs to suppress acid. Using these medications may help slow the progression of abnormal changes in the esophagus.

Surgery. Surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus may be considered when patients develop high-grade dysplasia of the cells lining the esophagus. Barrett's esophagus alone is not a reason to perform anti- reflux surgery, and is only recommended when other reasons for this surgery are present. See "Surgery" section.

Managing GERD in Infancy and Childhood

Here are some tips on managing GERD in infants:

- During and after feeding, infants should be positioned vertically and burped frequently.

- If a baby with GERD is fed formula, the mother should ask the doctor how to thicken it in order to prevent splashing up from the stomach.

- Parents of infants with GERD should discuss the baby's sleeping position with their pediatrician. The seated position should be avoided, if possible. Experts strongly recommend that all healthy infants sleep on their backs to help prevent sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). For babies with GERD, however, lying on the back may obstruct the airways. If the physician recommends that the baby sleeps on his stomach, the parents should be sure that the infant's mattress is very firm, possibly tilted up at the head, and that there are no pillows. The baby's head should be turned so that the mouth and nose are completely unobstructed. Carefully watch children who are placed on their stomach.

- Because food allergies may trigger GERD in children, parents may want to discuss a dietary plan with their physician that starts the child on formulas using non-allergenic proteins, and then incrementally adds other foods until symptoms are triggered.

- Proton-pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole (Prilosec) and lansoprazole (Prevacid), are drugs that suppress the production of stomach acid. The FDA has approved the PPI esomeprazole (Nexium) by injection for treatment of GERD with erosive esophagitis in children older than 1 month, in whom treatment with oral (by mouth) medication is not possible.

Managing GERD in Children. The same drugs used in adults may be tried in children with chronic GERD. While some drugs are available over the counter, do not give them to children without physician supervision.

- Changes in diet can include eliminating foods that are acidic or possibly associated with reflux, such as tomatoes, chocolate, mint, juices, and carbonated or caffeinated drinks.

- Obese children should try to lose weight.

- Milder medications, such as antacids, are used first. However, long-term use of these drugs is generally not recommended due to side effects such as diarrhea or constipation.

- PPIs may also be effective in children. A delayed-release capsule and liquid form of Nexium has been approved for the short-term (up to 8 weeks) treatment of GERD in children ages 1 - 11. The most common side effects were headache, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, gas, constipation, dry mouth, and sleepiness. Nexium capsules were previously approved for use in children ages 12 - 17, also for short-term GERD treatment. The PPI rabeprazole sodium (ACIPHEX) is approved for the short-term (up to 8 weeks) treatment of adolescents ages 12 and over. PPIs appear to be safe and effective even for children as young as 1 year old who fail the less intensive therapies. However, children treated with H2 blockers and PPIs may have an increased risk of developing respiratory and intestinal infections.

- H2 blockers are available over the counter and include famotidine (Pepcid AC), cimetidine (Tagamet HB), ranitidine (Zantac 75), and nizatidine (Axid AR). Note: The FDA has issued a warning on Pepcid AC for people with kidney problems -- see below in the Medications section.

Surgical fundoplication involves wrapping the upper curve of the stomach (fundus) around the esophagus. The goal of this surgical technique is to strengthen the LES. Until recently, surgery was the primary treatment for children with severe complications from GERD because older drug therapies had severe side effects, were ineffective, or had not been designed for children. However, with the introduction of PPIs, some children may be able to avoid surgery.

Surgical fundoplication can be performed laparoscopically through small incisions. Weakening of the LES over the long-term occurs with children as well as adults.

Medications

Antacids

Antacids neutralize acids in the stomach, and are the drugs of choice for mild GERD symptoms. They may also stimulate the defensive systems in the stomach by increasing bicarbonate and mucus secretion. They are best used alone for relief of occasional and unpredictable episodes of heartburn. Many antacids are available without a prescription. The different brands all rely on various combinations of three basic ingredients: magnesium, calcium, or aluminum.

Magnesium. Magnesium salts are available in the form of magnesium carbonate, magnesium trisilicate, and most commonly, magnesium hydroxide (Milk of Magnesia). The major side effect of magnesium salts is diarrhea. Magnesium salts offered in combination products with aluminum (Mylanta and Maalox) balance the side effects of diarrhea and constipation.

Calcium. Calcium carbonate (Tums, Titralac, and Alka-2) is a potent and rapid-acting antacid. It can cause constipation. There have been rare cases of elevated levels of calcium in the blood (hypercalcemia) in people taking large doses of calcium carbonate for long periods of time. This condition can lead to kidney failure and is very dangerous. None of the other antacids has this potential side effect.

Aluminum. Aluminum salts (Amphogel, Alternagel) are also available. The most common side effect of antacids containing aluminum salts is constipation. People who take large amounts of antacids that contain aluminum may also be at risk for calcium loss, which can lead to osteoporosis.

Although all antacids work equally well, it is generally believed that liquid antacids work faster and are more potent than tablets. Antacids can interact with a number of drugs in the intestines by reducing their absorption. These drugs include tetracycline, ciprofloxacin (Cipro), propranolol (Inderal), captopril (Capoten), and H2 blockers. Interactions can be avoided by taking the drugs 1 hour before, or 3 hours after taking the antacid. Long-term use of nearly any antacid increases the risk for kidney stones.

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors suppress the production of stomach acid and work by inhibiting the molecule in the stomach glands that is responsible for acid secretion (the gastric acid pump). Recent guidelines indicate that PPIs should be the first drug treatment, because they are more effective than H2 blockers. Once symptoms are controlled, patients should receive the lowest effective dose of PPIs.

The standard PPI has been omeprazole (Prilosec), which is now available over the counter without a prescription. Newer prescription oral PPIs include esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), rabeprazole (AcipHex), and pantoprazole (Protonix). In February 2009, the FDA approved the long-acting PPI dexlansoprazole (Kapidex), which is taken once a day.

Studies report significant heartburn relief in most patients taking PPIs. PPIs are effective for healing erosive esophagitis.

In addition to relieving most common symptoms, including heartburn, proton pump inhibitors also have the following advantages:

- They are effective in relieving chest pain and laryngitis caused by GERD.

- They may also reduce the acid reflux that typically occurs during strenuous exercise.

Patients with impaired esophageal muscle action are still likely to have acid breakthrough and reflux, especially at night. PPIs also may have little or no effect on regurgitation or asthma symptoms.

Currently, these drugs are recommended for patients with:

- Moderate symptoms that do not respond to H2 blockers

- Severe symptoms

- Respiratory complications

- Persistent nausea

- Esophageal injury

These medications have no effect on non-acid reflux, such as bile backup.

Adverse Effects. Proton-pump inhibitors may pose the following risks:

- Side effects are uncommon but may include headache, diarrhea, constipation, nausea, and itching.

- Long-term use of these drugs has been linked to an increased risk of hip, wrist, and spine fractures, possibly because stomach acid may be needed to absorb calcium from the diet. Patients who are on long-term PPI therapy may need to take a calcium supplement or the osteoporosis drugs, bisphosphonates to reduce their fracture risks.

- There is some evidence that PPIs increase the risk for community-acquired pneumonia, especially within the first 2 weeks of starting the medication. Researchers do not know the reason for this possible association. Newer research indicates that PPIs may also increase the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia.

- Pregnant women and nursing mothers should discuss the use of proton pump inhibitors with their health care provider, although recent studies suggest that PPIs do not pose an increased risk of birth defects.

- PPIs may interact with certain drugs, including anti-seizure medications (such as phenytoin), anti-anxiety drugs (such as diazepam), and blood thinners (such as warfarin). Studies have found that taking PPIs with the blood thinner clopidogrel (Plavix) reduces the effectiveness of this blood thinner by nearly 50%.

- Long-term use of high-dose PPIs may produce vitamin B12 deficiencies, but more studies are needed to confirm whether this risk is significant.

- A new warning added in May 2012 cautions that using certain PPIs with methotrexate, a drug commonly used

to treat certain cancers and autoimmune disorders, can lead to elevated levels of methotrexate in the blood, causing toxic side effects.

Some evidence suggests that acid reflux may contribute to the higher risk of cancer in Barrett's esophagus, but it is not yet confirmed whether acid blockers have any protective effects against cancer in these patients. Moreover, long-term use of proton pump inhibitors by people with H. pylori may reduce acid secretion enough to cause atrophic gastritis (chronic inflammation of the stomach). This condition is a risk factor for stomach cancer. To compound concerns, long-term use of PPIs may mask symptoms of stomach cancer and thus delay diagnosis. To date, however, there have been no reports of an increased risk of stomach cancer with the long-term use of these drugs.

There had been concerns that the PPIs Prilosec and Nexium might lead to heart attacks or cardiovascular problems. However, after a careful review, the FDA found no evidence of increased cardiovascular risk.

H2 Blockers

H2 blockers interfere with acid production by blocking or antagonizing the actions of histamine, a chemical found in the body. Histamine encourages acid secretion in the stomach. H2 blockers are available over the counter and relieve symptoms in about half of GERD patients. It takes 30 - 90 minutes for them to work, but the benefits last for hours. People usually take the drugs at bedtime. Some people may need to take them twice a day.

H2 blockers inhibit acid secretion for 6 - 24 hours and are very useful for people who need persistent acid suppression. They may also prevent heartburn episodes. In some studies, H2 blockers improved asthma symptoms in people with both asthma and GERD. However, they rarely provide complete symptom relief for chronic heartburn and dyspepsia, and they have done little to reduce physician office visits for GERD.

Brands. Four H2 blockers are available in the U.S.:

- Famotidine (Pepcid AC, Pepcid Oral). Famotidine is the most potent H2 blocker. The most common side effect of famotidine is headache, which occurs in 4.7% of people who take it. Famotidine is virtually free of drug interactions, but the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a warning on its use in patients with kidney problems.

- Cimetidine (Tagamet, Tagamet HB). Cimetidine is the oldest H2 blocker. It has few side effects, although about 1% of people taking it will have mild temporary diarrhea, dizziness, rash, or headache. Cimetidine interacts with a number of commonly used medications, such as phenytoin, theophylline, and warfarin. Long-term use of excessive doses (more than 3 grams a day) may cause impotence or breast enlargement in men. These problems get better after the drug is stopped.

- Ranitidine (Zantac, Zantac 75, Zantac EFFERdose, Zantac injection, and Zantac Syrup). Ranitidine may provide better pain relief and heal ulcers more quickly than cimetidine in people younger than age 60, but there appears to be no difference in older patients. A common side effect associated with ranitidine is headache, occurring in about 3% of people who take it. Ranitidine interacts with very few drugs.

- Nizatidine Capsules (Axid AR, Axid Capsules, Nizatidine Capsules). Nizatidine is nearly free from side effects and drug interactions. A controlled-release form can help alleviate nighttime GERD symptoms.

Drug Combinations.

- Over-the-counter antacids and H2 blockers: This combination may be the best approach for many people who get heartburn after eating. Both classes of drugs are effective in relieving GERD, but they have different timing. Antacids work within a few minutes but are short-acting, while H2 blockers take longer but have long-lasting benefits. Pepcid AC combined with an antacid (calcium carbonate and magnesium) is available as Pepcid Complete.

- Proton pump inhibitors and H2 blockers: Doctors sometimes recommend a nighttime dose of an H2 blocker for people who are taking PPIs twice a day. This is based on the belief that adding the H2 blocker will prevent a rise in acid reflux at night. Some experts recommended that patients who are on PPIs take an H2 blocker only to prevent breakthrough symptoms, such as before a heavy meal.

Long-Term Complications. In most cases, these medications have good safety profiles and few side effects. H2 blockers can interact with other drugs, although some less so than others. In all cases, the physician should be made aware of any other drugs a patient is taking. Anyone with kidney problems should use famotidine only under a doctor's direction. More research is needed into the effects of long-term use of these medications.

Concerns and Limitations. Some experts are concerned that the use of acid-blocking drugs in people with peptic ulcers may mask ulcer symptoms and increase the risk for serious complications.

These drugs do not protect against Barrett's esophagus. Also of concern are reports that long-term acid suppression with these drugs may cause cancerous changes in the stomach in patients who are infected with H. pylori. Research on this question is still ongoing.

FDA Warning for Famotidine (Pepcid AC)

Famotidine is removed primarily by the kidney. This can pose a danger to people with kidney problems. The FDA and Health Canada are advising physicians to reduce the dose and increase the time between doses in patients with kidney failure. Use of the drug in those with impaired kidney function can affect the central nervous system and may result in anxiety, depression, insomnia or drowsiness, and mental disturbances.

Medications that Protect the Mucus Lining (Sucralfate)

Sucralfate (Carafate) protects the mucus lining in the gastrointestinal tract. It seems to work by sticking to an ulcer crater and protecting it from the damaging effects of stomach acid and pepsin. Sucralfate may be helpful for maintenance therapy in people with mild-to-moderate GERD. Other than constipation, the drug has few side effects. Sucralfate interacts with a wide variety of drugs, however, including warfarin, phenytoin, and tetracycline.

Prokinetic Drugs

Metoclopramide (Reglan) is a drug that increases muscle contractions in the upper digestive tract. It is used for the short-term treatment of GERD-related heartburn in people who did not find relief from other medications. People with seizure disorders should not take metoclopramide. This drug can lead to a condition called tardive dyskinesia (TD) -- involuntary muscle movements, especially facial muscles. The longer a patient takes the drug, the higher the risk of developing TD. This condition may not resolve when the drug is stopped

Surgery

Surgical Management Of Barrett's Esophagus

Procedures to Remove the Mucus Lining. Various techniques or devices have been developed to remove the mucus lining of the esophagus. The intention is to remove early cancerous or precancerous tissue (high-grade dysplasia) and allow regrowth of new and hopefully healthy tissue in the esophagus.

Such techniques include photodynamic therapy (PDT), surgical removal of the abnormal lining, or ablation techniques, such as the use of laser, to destroy the abnormal lining. These techniques are done using an endoscope.

Patients with Barrett's esophagus who are most likely to benefit from these techniques have:

- A type of cancer of the esophagus called adenocarcinoma, but only when the cancer has not invaded deeper than the mucosal lining of the esophagus

- Pre-cancerous tissue called high-grade dysplasia

Unfortunately, the benefits do not last in all patients. These procedures also carry potential complications, such as swallowing problems, which patients should discuss with their physician.

Esophagectomy. Esophagectomy is the surgical removal of all or part of the esophagus. Patients with Barrett's esophagus who are otherwise healthy are candidates for this procedure if biopsies show they have high-grade dysplasia or cancer. After the esophagus is removed, a new conduit for foods and fluids must be created to replace the esophagus. Alternatives include the stomach, colon, and a part of the small intestine called the jejunum. The stomach is the optimal choice.

Surgery for GERD

The standard surgical treatment for GERD is fundoplication. The goals of this procedure are to:

- Increase LES pressure and prevent acid backup (reflux)

- Repair a hiatal hernia

There are two primary approaches:

- Open Nissen fundoplication (the more invasive technique)

- Laparoscopic fundoplication

Candidates. Fundoplication is recommended for patients whose condition includes one or more of the following:

- Esophagitis (inflamed esophagus)

- Symptoms that persist or come back in spite of antireflux drug treatment

- Strictures (or narrowing) in the esophagus

- Failure to gain or maintain weight (in children)

Fundoplication has little benefit for patients with impaired stomach motility (an inability of the muscles to move spontaneously).

The Open Nissen Fundoplication Procedure. Until recently, the Nissen fundoplication was the fundoplication procedure most often used for GERD. This is called an open procedure because it requires wide surgical incisions.

- With this procedure, the physician wraps the upper part of the stomach (fundus) completely around the esophagus to form a collar-like structure.

- The collar places pressure on the LES and prevents stomach fluids from backing up into the esophagus.

- Open fundoplication requires a hospital stay of 6 - 10 days.

Laparoscopic Fundoplication. The standard invasive fundoplication procedure has been replaced in many cases by a less invasive procedure that uses laparoscopy. In the operation:

- Tiny incisions are made in the abdomen.

- Small instruments and a tiny camera are inserted into tubes, through which the surgeon can view the region.

- The surgeon creates a collar using the fundus, although the area to work with is smaller.

When performed by experienced surgeons, results are equal to those of standard open fundoplication, but with a faster recovery time.

Overall, laparoscopic fundoplication appears to be safe and effective in people of all ages, even babies. Five years after undergoing laparoscopic fundoplication for GERD, patients report a near normal quality of life, and say they are satisfied with their treatment choice. Laparoscopic surgery also has a low reoperation rate -- about 1%.

Laparoscopy is more difficult to perform in certain patients, including those who are obese, who have a short esophagus, or who have a history of previous surgery in the upper abdominal area. It may also be less successful in relieving atypical symptoms of GERD, including cough, abnormal chest pain, and choking. In about 8% of laparoscopies, it is necessary to convert to open surgery during the procedure because of unforeseen complications.

Other Variations. There are now different fundoplication procedures.

- Toupet fundoplication and Thal fundoplication use only a partial wrap. Partial fundoplication procedures may be more effective in patients with poor or no esophageal muscle movement. Those with normal muscle movement may do better with the full-circle wrap.

- Other procedures use a very short and "floppy" Nissen full wrap.

Many surgeons report that such limited fundoplications help patients start eating and get released from the hospital sooner, and they have a lower incidence of complications (trouble swallowing, gas bloating, and gagging) than the full Nissan fundoplication.

Postoperative Problems and Complications after Fundoplication. Problems after surgery can include a delay in intestinal functioning, causing bloating, gagging, and vomiting. These side effects usually go away in a few weeks. If symptoms last or start weeks or months after surgery, particularly if there is vomiting, surgical complications are likely. Complications include:

- An excessively wrapped fundus. This is fairly common and can cause difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), as well as gagging, gas, bloating, or an inability to burp. (A follow-up procedure that dilates the esophagus using an inflated balloon may help correct dysphagia, although it cannot treat other symptoms.)

- Bowel obstruction

- Wound infection

- Injury to nearby organs

- Respiratory complications, such as a collapsed lung. These are uncommon, particularly with laparoscopic fundoplication.

- Muscle spasms after swallowing food. This can cause intense pain, and patients may need to eat a liquid diet, sometimes for weeks. This is a rare complication in most patients, but the risk can be very high in children with brain and nervous system (neurologic) abnormalities. Such children are already at very high risk for GERD.

Outcomes. In general, the long-term benefits of these procedures are similar. Fundoplication relieves GERD-induced coughing and other respiratory symptoms in up to 85% of patients. (Its effect on asthma associated with GERD, however, is unclear.) Many patients still require anti-GERD medications or experience new symptoms (such as gas, bloating, and trouble swallowing) after surgery. Most of these new symptoms occur more than a year after surgery. Fundoplication does not cure GERD, and evidence suggests that the procedure does not reduce the risk for esophageal cancer in high-risk patients, such as those with Barrett's esophagus. However, fundoplication has very good long-term results, especially when performed by an experienced surgeon, and few patients need to have a repeat procedure.

Reasons for Treatment Failure. Some studies have reported that 3 - 6% of patients need repeat operations, usually because of continuing reflux symptoms and swallowing difficulty (dysphagia). Repeat surgery usually has good success. However, these surgeries can also lead to greater complications, such as injury to the liver or spleen.

Surgical Treatments Using Endoscopy

A number of endoscopic treatments are being used or investigated for increasing LES pressure and preventing reflux, as well as for treating severe GERD and its complications. Researchers find that endoscopic therapies for GERD may relieve symptoms and reduce the need for antireflux medications, although they are not as effective as laparoscopic fundoplication. Endoscopic procedures are also being done along with fundoplication.

Transoral Flexible Endoscopic Suturing. Transoral flexible endoscopic suturing (sometimes referred to as Bard's procedure) uses a tiny device at the end of the endoscope that acts like a miniature sewing machine. It places stitches in two locations near the LES, which are then tied to tighten the valve and increase pressure. There is no incision and no need for general anesthesia.

Radiofrequency. Radiofrequency energy generated from the tip of a needle (sometimes called the Stretta procedure) heats and destroys tissue in problem spots in the LES. Either the resulting scar tissue strengthens the muscle, or the heat kills the nerves that caused the malfunction. Patients may experience some chest or stomach pain afterward. Few serious side effects have been reported, although there have been reports of perforation, hemorrhage, and even death.

Dilation Procedures. Strictures (abnormally narrowed regions) may need to be dilated (opened) with endoscopy. Dilation may be performed by inflating a balloon in the passageway. About 30% of patients who need this procedure require a series of dilation treatments over a long period of time to fully open the passageway. Long-term use of PPIs may reduce the duration of treatments.

Resources

- http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov -- National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

- www.gastro.org -- American Gastroenterological Association

- www.acg.gi.org -- American College of Gastroenterology

- www.asge.org -- American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

- www.ssat.com -- Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract

- www.naspghn.org -- North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition

- www.reflux.org -- Pediatric/Adolescent Gastroesophageal Reflux Association

- www.iffgd.org -- International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

References

Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceuticals Partnership. Plavix Prescribing Information. March 2010. Available online.

Friedenberg FK, Xanthopoulos M, Foster GD, Richter JE. The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2111-2122.

Galmiche JP, Hatlebakk J, Attwood S, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(19):1969-1977.

Gee DW, ANdreoli MT, Rattner DW. Measuring the effectiveness of laparoscopic antireflux surgery: long-term results. Arch Surg. 2008;143:482-487.

Herzig SJ, Howell MD, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Acid-suppressive medication use and the risk for hospital-acquired pneumonia. JAMA. 2009;301:2120-2128.

Hirano I, Richter JE, and the Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. ACG practice guidelines: esophageal reflux testing. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;102:668-685.

Islami F, Kamangar F. Helicobacter pylori and esophageal cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res. 2008;1:329-338.

Jeansonne LO, White BC, Nguyen V, Jafri SM, Swafford V, Katchooi M, et al. Endoluminal full-thickness plication and radiofrequency treatments for GERD: An outcomes comparison. Arch Surg. 2009;144:19-24.

Kahrilas PJ, Shaheen NJ, Vaezi MF, Hiltz SW, Black E, Modlin IM. American Gastroenterological Association Medical Position Statement on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1383-1391.

Khan S, Orenstein S. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). In: Kliegman: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011:chap 315.

Petersen RP, Pellegrini CA, Oelschlager BK, . Hiatal Hernia and Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. In: Townsend: Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, 19th ed. Philadelphia, PA:WB Saunders; 2012:chap 44.

Richter JE, Friedenberg FK. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. In: Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2010. pp.705-726.

Sharma P. Clinical practice. Barrett's esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(26):2548-2556.

Targownik LE, Lix LM, Metge CJ, Prior HJ, Leung S, Lesie WD. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of osteoporosis-related fractures. CMAJ. 2008;179:319-326.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Consumer Health Information. Possible Increased Risk of Bone Fractures With Certain Antacid Drugs. May 2010. Available online.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Safety Labeling Changes, May 2012. Available online.

Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(3):788-97.

Wilson JF. In The Clinic: Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3):ITC2-1-15.

|

Review Date:

10/29/2012 Reviewed By: Reviewed by: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |