Prostate cancer

Highlights

Drug Approvals

- In 2012, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a new anti-androgen drug, enzalutamide (Xtandi), for patients with advanced prostate cancer who have already received chemotherapy with docetaxel. Enzalutamide is the latest drug approved for advanced prostate cancer in the last several years. The other new drugs are abiraterone (Zytiga), which like enzalutamide is an anti-androgen taken as a once-daily pill, the chemotherapy drug cabazitaxel (Jevtana), and the prostate cancer “vaccine” sipuleucel-T (Provenge).

- In 2011, the FDA approved denosumab (Prolia) as a treatment to increase bone mass in men receiving androgen-deprivation therapy for non-metastatic prostate cancer. (Osteoporosis and bone thinning is a side effect of hormone therapy treatment for prostate cancer.)

Prostate Cancer Screening Guidelines

In 2012, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended against prostate cancer screening for all men, regardless of age, who do not have symptoms. The USPSTF based its recommendations on concerns regarding the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) blood test. According to the USPSTF, evidence indicates that PSA screening offers “a very small potential benefit and significant potential harm” from unnecessary treatment.

The American Cancer Society’s guidelines for early detection of prostate cancer recommend that men discuss with their doctors the uncertainties, risks, and potential benefits of screening for prostate cancer before deciding whether to be tested.

Debate continues over whether the benefits of prostate specific antigen (PSA) screening outweigh the treatment risks for most men. In general, the current consensus is that there is no "one size fits all" guideline for who should receive prostate cancer screening and at what age. It is important to discuss with your doctor your questions and concerns regarding prostate cancer screening.

Vitamin E Supplements May Increase Risk for Prostate Cancer

High doses (400 IU daily) of vitamin E supplements do not help prevent prostate cancer and may, in fact, significantly increase risk in healthy men, according to a follow-up of the Selenium and Vitamin E Prevention Trial (SELECT). Researchers studied 35,000 men over the course of 7 years. The results were published in 2011 in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Introduction

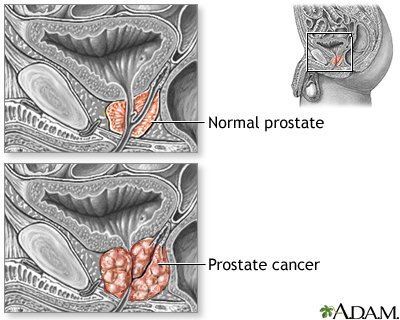

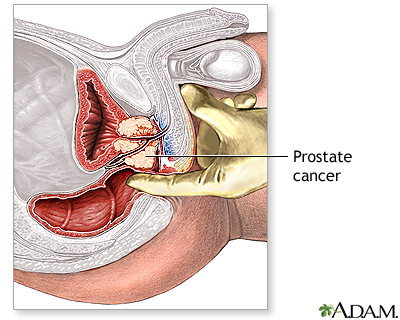

Prostate cancer is a malignant tumor that originates in the prostate gland. As with any cancer, if it advances or is left untreated in early stages, it may eventually spread through the blood and lymph fluid to other organs. Fortunately, prostate cancers tend to be slow growing compared to other cancers. Most older men eventually develop at least microscopic evidence of prostate cancer, but it often grows so slowly that many men with prostate cancer "die with it, rather than from it."

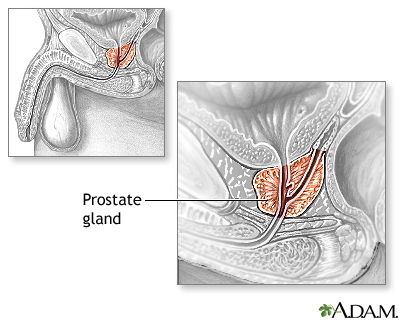

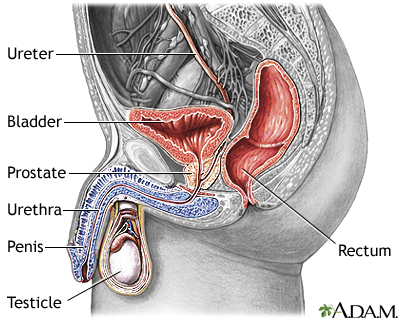

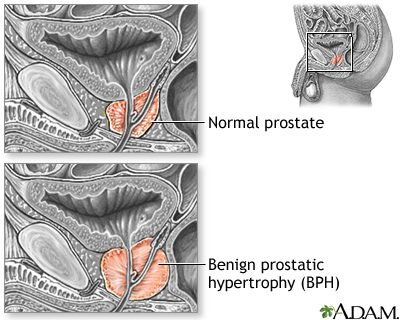

Description of the Prostate GlandThe prostate is a walnut-shaped gland located below the bladder and in front of the rectum. It wraps around the urethra (the tube that carries urine through the penis). The central area of the prostate that wraps around the urethra is called the transition zone. The entire prostate gland is surrounded by a dense, fibrous capsule. Functions of the Prostate GlandThe prostate gland provides the following functions:

Changes During the LifespanThe prostate gland undergoes many changes during the course of a man's life. At birth, the prostate is about the size of a pea. It grows only slightly until puberty, when it begins to enlarge rapidly, attaining normal adult size and shape, about that of a walnut, when a man reaches his early 20s. The gland generally remains stable until men reach their mid-40s, when, in most men, the prostate begins to enlarge again through a process of cell multiplication. |

Risk Factors

The major risk factors for prostate cancer are age, family history, and ethnicity.

Age

Prostate cancer occurs almost exclusively in men over age 40 and most often after age 50. The average age at diagnosis is about 67. By age 70, about two-thirds of men have at least microscopic evidence of prostate cancer. Fortunately, the cancer is usually very slow growing, and older men with the cancer typically die of something else, often without even knowing they have prostate cancer.

Family History and Genetic Factors

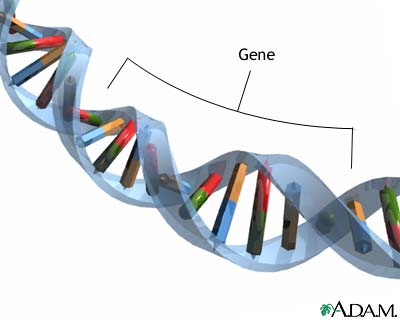

Heredity plays a role in some types of prostate cancers. Men with a family history of the disease have a higher risk of developing prostate cancer. Having one family member with prostate cancer doubles a man's own risk, and having three family members increases risk by 11-fold. A specific gene, named HPC1 (for “hereditary prostate cancer”) was the first of several genes linked to inherited types of the disease.

Scientists are researching other genetic variations that may increase prostate cancer risk.

Race and Ethnicity

African-American men have higher rates of prostate cancer than men of other races. They are also more likely to develop prostate cancer at a younger age and to have more aggressive forms of the disease. However, race alone does not fully explain this difference. Prostate cancer is more common in North America and northern Europe and less common in Africa, Latin America, and Asia. Diet and other factors may play a role. For example, Asians who live in the United States have a higher rate of prostate cancer than those who live in Asia.

Hormones

Male hormones (androgens), particularly testosterone, may play a role in the development or aggressiveness of prostate cancer. Other types of hormones, such as the growth hormone insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), may also be associated with some types of prostate cancer.

Inflammation and Infection

Prostatitis (inflammation of the prostate gland) may possibly be associated with increased prostate cancer risk. There may also be a possible relationship between prostate cancer and sexually transmitted infections, such as herpes virus and human papillomavirus, but no definite association has yet been proven.

Dietary Factors

Because a Western lifestyle is associated with prostate cancer, dietary factors have been intensively studied. Results have been inconsistent and inconclusive, however.

Fats. Some studies have found an association between high fat intake and prostate cancer. In particular, high consumption of red meat and high-fat dairy products has been linked to increased risk for prostate cancer. In contrast, the omega-3 fats found in certain fish (salmon, sardines, fresh tuna) may be protective.

Vegetables and Fruits. A diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and legumes appears to protect against prostate cancer. However, it is not clear whether this is due to the nutrients contained in these foods, or the fact that these foods are low in fat. No specific vegetable or fruit has been proven to decrease risk. Lycopene, which is found in tomatoes, has been a target of research interest, but the evidence for its protective benefit is still inconclusive.

Vitamins and Minerals. Major clinical studies have found that vitamin and mineral supplements (vitamin E, vitamin C, vitamin D, and selenium) do not prevent prostate cancer. (Researchers studying whether high doses [400 IU daily] of vitamin E supplements could reduce the risk of prostate cancer found that they had the opposite effect and actually increased risk.) Nutritious foods that are part of a healthy diet are the best sources for vitamins and minerals. A high intake of calcium has been linked to an increased risk of prostate cancer in some studies.

Possible Preventive Factors

The below factors may help reduce the risk of developing prostate cancer.

Diet. Eat a healthy diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and legumes (beans). Limit consumption of red meat and high-fat dairy products. There is some evidence that a low-fat diet may help protect against prostate cancer.

Weight and Exercise. Maintain a healthy weight through diet and regular physical activity.

5-ARIs (Controversial). If you’re at higher-than-average risk for prostate cancer, you may wish to discuss with your doctor whether 5-ARI medications may help lower your risk. The 5-ARI drugs finasteride (Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart) are prescribed to help improve urinary symptoms associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH ). Some studies have suggested that 5-ARIs may lower a man’s risk for developing prostate cancer. However, based on other studies, the FDA revised these drugs’ prescribing labels to indicate that 5-ARIs may increase the risk for being diagnosed with high-grade aggressive types of prostate cancer. At this time, 5-ARIs are not approved for prostate cancer prevention and their use for this purpose is controversial.

Prognosis

Prostate cancer is the most common internal cancer in American men. (For men, skin cancer is the most common cancer, and only lung cancer causes more cancer deaths.) About 1 in 6 men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer over the course of their life. But because so many prostate tumors are low-grade and slow growing, and men are usually older when they are diagnosed with it, most men diagnosed with prostate cancer eventually die of something else.

At the time of diagnosis, most men have localized prostate cancer (cancer confined to the prostate gland). The prognosis for men with localized prostate cancer is excellent. Nearly 100% of men with localized prostate cancer live at least 5 years after diagnosis. The same is true for men with regional prostate cancer, which means the cancer has spread from the prostate gland to nearby areas in the body.

Only about 5% of men are diagnosed with advanced or distant cancer that has spread throughout the body. For these men, the 5-year relative survival rate is 29%.

A survival rate indicates the percentage of patients who live a specific number of years after the cancer is diagnosed. A relative survival rate compares the survival of people with a specific type of cancer to the expected survival of people who do not have cancer and will die from other causes.

Overall, for prostate cancer, the 10-year relative survival rate is about 98% and the 15-year survival rate is about 91%. After 15 years, survival rates stabilize.

The odds of survival depend in part on how far advanced the cancer is when a man is first diagnosed. Men who are diagnosed with low-grade prostate cancers have a minimal risk of dying from prostate cancer for up to 20 years after diagnosis. However, men diagnosed with more aggressive forms of prostate cancer have a higher risk of dying within 10 years.

If cancer recurs after initial treatment for early-stage tumors, it is still potentially curable if it is contained within the prostate, although in most cases the cancer has spread. Hormone treatments for such recurring cancers can often prolong survival for years, although the cancer almost always returns again.

Symptoms

Prostate cancer usually causes no symptoms in the early stages. As the malignancy spreads, it may constrict the urethra and cause urinary problems.

Later Stage Urinary Symptoms

Later-stage urinary symptoms may include:

- Weak urinary stream

- Inability to urinate

- Blood in the urine

- Interruption of urinary stream (stopping and starting)

- Frequent urination (especially at night)

- Pain or burning during urination

Although advanced prostate cancer can cause these symptoms, they are more commonly caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia and other non-cancerous conditions.

Late Stage General Symptoms

Significant pain in one or more bones may indicate the occurrence of metastases (spread of disease). This chronic pain occurs most often in the spine and sometimes flares in the pelvis, the lower back, the hips, or the bones of the upper legs. It may be accompanied by significant unexplained weight loss and fatigue.

Conditions with Similar Symptoms

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH). BPH is a urinary condition that can develop into an enlarged prostate, which puts pressure on the urethra and causes urinary problems. BPH is not a cancerous or precancerous condition, but its symptoms can mimic late-stage prostate cancer.

Prostatitis. Prostatitis is an inflammation of the prostate, often caused by bacterial infections. Symptoms include urgency, frequency, and pain in urination, sometimes accompanied by fever or blood in the urine.

Diagnosis

Screening for Prostate Cancer

The goal of screening is to find cancer at an early stage before it has caused symptoms. To be considered successful, a screening test should lead to treatments that prolong life or reduce discomfort and improve the quality of life.

Two standard screening tests are used for early detection of prostate cancer:

- PSA test. The PSA blood test measures the blood level of a protein called prostate-specific antigen. Prostate specific antigen is a protein produced in the prostate gland that keeps semen in liquid form. Prostate cancer cells appear to produce this protein in elevated quantities.

- Digital rectal examination (DRE). The DRE is a physical examination. The doctor inserts a gloved and lubricated finger into the patient's rectum and feels the prostate for bumps or other abnormalities.

There is great uncertainty and controversy over whether the benefits of regular screening for prostate cancer outweigh the risks for most men. Prostate cancer is very common, especially among older men, and is usually slow growing. Doctors cannot yet predict accurately which early-stage tumors pose a risk of being aggressive and need treatment, and which tumors should be left alone. The concern is that routine screening for early detection of tumors may lead to invasive and unnecessary treatment.

The controversy over prostate cancer screening centers on the use of the PSA test as a screening tool. The test is not accurate enough to either rule out or confirm the presence of cancer. PSA levels are often elevated in men with prostate cancer. However, PSA levels can be increased by various factors other than prostate cancer, including benign prostatic hyperplasia, prostatitis, advanced age, and ejaculation within 48 hours of the test.

The main concern is that PSA screening may result in the detection of some cancers that would never have bothered the patient and would never have posed a threat to his life. Many older men are less likely to die from prostate cancer than heart disease and other problems. Relying too much on the test may lead to unnecessary biopsies and potentially harmful treatments. Several major studies have found that PSA screening saves few if any lives. The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) currently recommends against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer.

The American Cancer Society (ACS) recommends that starting at age 50, men should discuss with their doctors the pros and cons of having a PSA test with or without a digital rectal exam. Men who are at higher-than-average risk for prostate cancer (including those with a family history of prostate cancer and all African-Americans) should initiate this talk at age 45. When and how often a man should be retested depends on his PSA level.

Tests to Diagnose Prostate Cancer

Biopsy. If cancer is suspected, the doctor will order a biopsy. Only a biopsy, in which a tiny sample of prostate tissue is surgically removed, can actually confirm a diagnosis of prostate cancer. A biopsy is usually performed to confirm or rule out cancer based on a combination of PSA test levels, findings on the DRE, family history, and patient’s age and ethnicity. If a biopsy gives a negative result but the doctor still suspects cancer, repeat biopsies may be performed.

An ultrasound procedure called transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) may be used to help the doctor see where to take the needle biopsy. Ultrasound is not effective as a diagnostic tool by itself because it cannot differentiate very well between benign inflammations and cancer.

Tests after Cancer is Diagnosed

PSA Levels and Velocity. Once cancer is diagnosed, PSA levels may help to determine its extent. If PSA levels are lower than 20 ng/mL, it is likely that the cancer has not spread to distant sites. PSA levels over 40 ng/mL are a strong indicator that cancer has metastasized (spread elsewhere in the body). PSA levels are also monitored after treatments begin. Changes in the level can show if a treatment is working or if the cancer has come back.

Doctors also monitor how quickly PSA levels rise over time. This rate is called PSA velocity (PSAV). The PSAV may help determine when treatment should begin and which treatment should be used. A high rate of PSAV is considered to be 2 ng/mL a year. Recent research suggests that men with early-stage prostate cancer who have a slow PSAV are more likely to live longer than men with rapidly rising PSA levels.

Test for Metastasis. If the biopsy indicates cancer, and the PSA is above 20 ng/mL, the doctor will order other tests to determine whether or how far the cancer has spread:

- Bone scans and x-rays may reveal whether the cancer has invaded the bones. To perform a bone scan, the doctor injects a low dose of a radioactive substance into the patient's vein, which accumulates in bones that have been damaged by cancer. A scanner then reveals how much of the radioactive material has accumulated.

- Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans can further pinpoint the location of cancer that has spread beyond the prostate.

Staging and Grading

Grading refers to how abnormal the cells look under a microscope and how likely the cancer is to advance and spread. A pathologist will read the biopsy report and assign a grade to the tumor cells using the Gleason system of scoring.

Staging refers to the extent the cancer has spread. Based on the grade, TNM staging system, PSA test result, digital rectal exam, and possibly imaging tests, the doctor stages the cancer. The overall stage of cancer can help the doctor determine treatment options.

The Gleason Grading System

Gleason Grade. The Gleason system grades tumors on a scale of 1 - 5 based on how well or poorly differentiated the cancer cells look under a microscope. Grade 1 means that the cells resemble normal prostate tissue. Grade 5 means that the cells look very abnormal and are poorly organized throughout the prostate. Grades 2 - 4 fall in between with cells showing increasingly irregular features.

Gleason Score. Most prostate cancers contain a mix of tumor grades. To determine a Gleason score, two numbers are assigned, representing the dominant grade and then the minor grade. The cancer is then "scored" by adding the dominant grade plus the minor grade. For example, a tumor with a dominant grade of 3, and a minor grade of 4 is given a Gleason score of 7.

Gleason scores range from 2 - 10. A higher score means that the cancer cells look very different from normal cells. A higher score also means that it is more likely that the tumor will spread aggressively. In general, Gleason scores indicate:

- Scores 2 - 4: G1. Low-grade cancer (well-differentiated cells)

- Scores 5 - 7: G2. Intermediate-grade cancer (moderately-differentiated cells). Most prostate cancers fall into this category, making it difficult to predict their development.

- Scores 8 - 10: G3 - 4. High-grade cancer (poorly-differentiated cells)

TNM Staging System

A tumor's stage is an indication of how far it has spread from its original site. Cancers are staged according to whether they are still localized (still within the prostate gland) or have spread beyond the original site. The current prostate cancer staging system is the TNM system.

The TNM system refers to clinical tumor stages as:

- T for tumor

- N for regional lymph nodes

- M for metastasis (tumors developing outside the prostate)

T Stages

T followed by numbers 0 through 4 refers to the size and extent of the tumor itself.

Stage, T1 - T4 | Description |

T1 | The tumor cannot be felt or seen using imaging techniques. |

T1a. Cancer cells are incidentally found in 5% or less of tissue samples from prostate surgery unrelated to cancer. | |

T1b. Cancer cells found in more than 5% of samples. | |

T1c. Cancer cells identified by needle biopsy, which is performed because of high PSA levels. | |

T2 | The cancer is confined to the prostate but can be felt as a small well-defined nodule. |

T2a. Tumors are in half a prostate lobe. | |

T2b. Tumors are in more than half a lobe. | |

T2c. Tumors in both lobes. | |

T3 | The tumor extends through the prostate capsule. |

T4 | The tumor is fixed to or invades adjacent structures. |

N Stages

N followed by 0 through 3 refers to whether the cancer has reached the regional lymph nodes, which are located next to the prostate in the pelvic region.

Stage, N0 - N3 | Description |

N0 | Regional lymph nodes are still cancer-free. |

N1 | A small tumor is in a single pelvic node. |

N2 | A medium-size tumor is in one node, or small tumors are in several nodes. |

N3 | A large tumor is in one or more nodes. |

M Stages

M stages refer to metastasis (tumors developing outside the prostate).

Stage | Description |

M0 | Metastasis has not occurred (cancer has not spread beyond the regional lymph nodes). |

M1a | Cancer has spread to lymph nodes beyond the regional lymph nodes. |

M1b | Cancer has invaded the bones. |

M1c | Cancer has spread to other sites. |

The T, N, and M stages are used along with the grade, PSA test result, and other factors to determine the overall stage of the cancer:

- Stage I and stage II cancer are considered early stage. The cancer is localized and has not spread outside the prostate gland.

- Stage III, locally advanced cancer, means that the cancer has spread into the seminal vesicles (glands at the base of the bladder, which are connected to the prostate gland and help produce semen).

- Stage IV is advanced cancer. The cancer has spread to the lymph nodes and other tissues or organs.

[For more information on staging, see Treatment section of this report.]

Treatment

Treatment choices are generally based on the patient's age, the stage and grade of the cancer, overall health status, and the patient's personal preferences for the risks and benefits of each therapy.

Patients should be aware that doctors may prefer a specific treatment depending on their specialty, with urologists and medical oncologists tending to recommend watchful waiting, surgery, or hormone therapy and radiation oncologists recommending radiation therapy. It is always wise to seek a second opinion. Delaying treatment, while having the cancer monitored for signs of progression, is also an acceptable option.

Depending on the cancer stage and other factors, patients have four main treatment options:

- Active surveillance, formerly called watchful waiting, involves monitoring the tumor for cancer progression to determine if and when treatment should be started.

- Surgery (radical prostatectomy) removes the prostate gland. The vessels that carry semen and surrounding tissue may also be removed. Studies indicate that compared to watchful waiting, radical prostatectomy may lower the risk of cancer recurrence and death, particularly for younger men with aggressive tumors. It is usually not appropriate for older men. Radical prostatectomy may be done either through open surgery or using laparoscopic or robotic techniques.

- Radiation therapy targets the tumor either externally (external beam radiation) or internally (implanted “seeds”).

- Androgen deprivation therapy, also called hormone therapy, uses orchiectomy (surgical removal of the testicles) or drugs to stop production of male hormones.

The U.S. National Cancer Institute recommends the following treatment options by cancer stage:

Stage I Treatment Options (Localized Cancer)

Tumors: T1a, N0, M0, G1

- Active surveillance

- Radical prostatectomy, which may be followed by radiation therapy

- External beam radiation therapy

- Implant radiation therapy (brachytherapy)

- Clinical trial options

Stage II Treatment Options (Localized Cancer)

Tumors: T1a - c, N0, M0, any G

- Radical prostatectomy, with or without pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiation therapy may follow surgery.

- Active surveillance

- External beam radiation therapy with or without hormone therapy

- Implant radiation therapy (brachytherapy)

- Clinical trial options

Overview of Treatment Options for Localized Prostate Cancer. To date, neither treatment nor active surveillance has emerged with a definitive survival advantage for localized prostate cancer. However, research suggests that treatment may provide a survival advantage over watchful waiting for some men with early-stage prostate cancer. The men who are most likely to benefit from active treatment include those younger than 65 with good general health and PSA levels above 10.

Recent guidelines recommend that patients with localized cancer should be classified as low, intermediate, or high risk. Doctors determine the risk category by using criteria such as PSA tests, tumor aggressiveness, and the clinical stage of the tumor. Based on these risk groups, evidence indicates that:

- Compared with active surveillance, radical prostatectomy may lower the risk of cancer recurrence and death, at least in men younger than age 65 at the time of diagnosis.

- For men at intermediate and high risk, adding androgen deprivation (hormonal) therapy to external beam radiation may improve survival but increase adverse side effects. Adding hormonal therapy to radical prostatectomy does not improve survival or cancer recurrence rates.

- Initial (first-line) androgen deprivation therapy is seldom recommended for localized prostate cancer except for the relief of symptoms in patients with poor prognoses. Androgen deprivation therapy can increase the risks for diabetes and heart disease.

- Patients with localized prostate cancer should have the opportunity to enroll in clinical trials investigating new types of therapy.

Stage III Treatment Options (Locally Advanced Cancer)

Tumors: T3, N0, M0, any G

- External beam radiation with or without androgen deprivation therapy (hormone therapy)

- Androgen deprivation therapy

- Radical prostatectomy, with or without pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiation therapy may follow surgery

- Radiation therapy, androgen deprivation therapy or transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) to relieve symptoms

- Clinical trial options

Stage IV Treatment Options (Advanced Cancer)

Tumors: Any T, any N, any M, any G

- Androgen deprivation therapy

- External beam radiation therapy with or without androgen deprivation therapy

- Radiation therapy or transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) to relieve symptom

- Clinical trial options

Recurrent or Persistent Prostate Cancer

If prostate cancer has been by radical prostatectomy, PSA levels should drop to zero after surgery. After radiation, PSA levels do not drop as far because some of the prostate gland remains. A sudden rise or persistently elevated PSA levels after treatment are often indications that prostate cancer persists.

It is common for PSA levels to temporarily rise or "bounce" following radiation seed implantation without signaling cancer recurrence. Rising PSA levels do not necessarily mean that the cancer has spread or even that clinical cancer will recur during a man's lifetime.

Treatment options for recurrent cancer depend on various factors, including prior treatment, site of recurrence, coexistent illnesses, and individual patient considerations.

- Patients whose cancer recurs locally after prostatectomy: Radiation therapy, androgen deprivation therapy.

- Patients whose cancer recurs locally after radiation therapy: Androgen deprivation therapy, prostatectomy (very select patients), cryosurgery.

- Patients whose recurrent cancer has spread: Androgen-deprivation therapy including newer drug treatments, chemotherapy, “vaccine” therapy with sipuleucel-T (Provenge), clinical trial options.

Comparing Side Effects of Treatments

Prostate cancer treatments can cause distressing side effects by impairing sexual function (erectile dysfunction), urination (incontinence or urinary bleeding), bowel function (incontinence), and energy levels (fatigue). A man must weigh his own emotional responses to the possibility of these side effects versus the possible stress of active surveillance.

Side effects vary among patients and it is difficult to predict how an individual patient will respond. In general, the side effects most likely to occur by treatment modality are:

- External beam radiation therapy provides the best initial results for recovery of sexual function.

- Nerve-sparing prostatectomy generally produces better sexual function than conventional radical prostatectomy.

- External beam radiation therapy produces better urinary control and sexual function than brachytherapy, but brachytherapy has better results for these side effects than radical prostatectomy.

- Radiotherapy (both brachytherapy and external beam radiation) generally causes more bowel problems than surgery, although this side effect usually improves after 1 year. Urinary incontinence is less common after radiation than after surgery.

Active Surveillance (Watchful Waiting)

Active surveillance involves lifestyle change and careful monitoring of cancer with conversion to active therapy if the disease progresses. With this approach, patients have a digital rectal exam and PSA blood test every 6 - 12 months. If test results indicate cancer progression, doctor and patient consider treatment options (surgery, radiation, or drugs). Patients should exercise and eat healthy foods. Patients should report symptoms such as weight loss, pain, urinary problems, fatigue, or erectile dysfunction to their doctors. Active surveillance was formerly called “watchful waiting.” Watchful waiting is now mostly associated with palliative measures for advanced cancer.

Active surveillance may be most appropriate for the following patients:

- Men in their late 70s and older. More aggressive therapies (surgery and radiation) are usually recommended for men in their 50s and younger. The choice for men in their 60s and early 70s is more problematic. The general recommendation is that aggressive therapy is suitable for those who have a life expectancy of more than 10 years and who have localized but mid- to high-grade tumors. The tumor grade may be the best guide for determining the risks in choosing active surveillance.

- Elderly men with early-stage (T0 - T2) low-grade tumors.

- Men with low-to-moderate (3 - 13 ng/mL) PSA levels.

Some doctors think that because prostate cancer grows so slowly, it is likely that older men will die from causes unrelated to the cancer. There is therefore little potential benefit from surgery or radiation, with both posing a risk for erectile dysfunction and incontinence. The choice is a difficult one. It is important that patients find a doctor who can provide them with all the necessary information so that they can make an informed decision.

Surgery

In men whose cancer is confined to the prostate, surgical resection (radical prostatectomy) offers the potential for cure. Most patients can consider themselves disease-free if their PSA levels remain undetectable 10 years after surgery.

Radical Prostatectomy

Radical prostatectomy is the surgical removal of the entire prostate gland along with the seminal vesicles (the vessels that carry semen) and surrounding tissue. The surgeon may also remove the pelvic lymph nodes (a procedure called pelvic lymphadenectomy). The incision can be made in one of the following regions:

- Retropubically (through the abdomen and under the pubic bone, exposing the entire surface of the prostate). This is the approach used most often.

- Through the perineum (the skin between the scrotum and the anus). The perineal approach causes less bleeding and has a shorter recovery time, but it makes it more difficult to preserve nerves and remove lymph nodes. This approach is now rare.

The gland and other structures are then removed. The operation lasts 2 - 4 hours.

Minimally Invasive Prostatectomy. Less invasive surgical techniques with laparoscopy use smaller incisions and allow faster recovery, but they require special surgical training. Laparoscopic surgery inserts an instrument with a small video camera attached to it to help guide the surgeon. Robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical prostatectomy involves the surgeon directing a robotic arm through a computer monitor. Not every hospital can do robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy, and these procedures are difficult to perform. Although robotic surgery is gaining popularity, it is not clear that it produces better results than traditional operations.

Nerve-Sparing Techniques. In retropubic open surgery, laparoscopic surgery, and robot-assisted surgery, the surgeon will attempt to spare the nerves that control erection:

- A bilateral nerve-sparing procedure saves the nerves on both sides of the sex organs.

- A unilateral procedure saves nerves on only one side.

Nerve-sparing techniques can improve quality of life, by decreasing the occurrence of incontinence and erectile dysfunction. In cases where the tumor lies too closely to the nerve, nerve-sparing techniques may not be possible.

Recuperation. Patients remain hospitalized for about 3 days after an open procedure or 2 days after less invasive procedure. Full recovery at home takes about 3 - 5 weeks. A temporary catheter used to pass urine is kept in place when the patient is sent home and is usually removed about 3 weeks after the open operation or 1 week after a minimally invasive procedure. In general, younger patients with early-stage cancers recover fastest and experience the fewest side effects.

Complications from Radical Prostatectomy

The main complications from radical prostatectomy are urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Other complications include the usual risks of any surgery, such as blood clots, heart problems, infection, and bleeding. Minimally invasive procedures usually result in less pain and a faster return to activity.

Urinary Incontinence. Urinary incontinence is a common complication. When the urinary catheter is first removed following surgery, nearly all patients lack control of urinary function and will leak urine for at least a few days and sometimes for months. Normal urinary function usually returns within about 18 months. A percentage of men will continue to have small amounts of leakage with heavier exertion or possibly sexual activity.

If incontinence persists beyond a year, patients may require drug therapy or surgery.

Erectile Dysfunction. Erectile dysfunction after radical prostatectomy is caused by nerves that were damaged or removed during the surgery. Virtually all men will have problems with erectile dysfunction after surgery. It can take up to 1 to 2 years to recover erectile function after surgery. Because seminal glands are removed along with the prostate gland during surgery, men who regain sexual function will not produce semen during orgasm (“dry ejaculation”).

With the use of nerve-sparing techniques, men below age 60 who were sexually active before surgery seem to have a better chance of returned sexual function. PDE5 inhibitor drugs such as sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), tadalafil (Cialis), or avanafil (Stendra) may help some men regain erectile function. Other treatments for erectile dysfunction(alprostadil injections, vacuum devices, penile implants) may also be options.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy may be used as an initial treatment for localized prostate cancer. It may also be used as treatment for cancer that has not been fully removed or has recurred after surgery. In advanced cancer, radiation therapy is used to shrink the size of the tumor and relieve symptoms.

The two main radiation treatments for prostate cancer are:

- External beam radiation

- Brachytherapy (internal radiation)

In some cases, both techniques may be used to treat high-risk patients.

External Beam Radiation

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) uses a machine that focuses a beam of radiation directly on the tumor. An EBRT treatment lasts a few minutes and is given 5 times a week over the course of 7 - 9 weeks. Doctors use imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to precisely map out where the beams are aimed at the tumor cells.

Newer types of EBRT allow doctors to increase radiation doses while minimizing damage to nearby tissue. Higher radiation doses may reduce the risk for cancer recurrence and improve survival outcome. Three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy (3D-CRT) uses a computerized program and three-dimensional image of the prostate to precisely target the tumor. Other techniques related to 3D-CRT include:

- Intensity modulated radiation beam therapy (IMRBT) is an advanced form of 3D-CRT. With IMRBT, the doctor can adjust the doses of the radiation beams so that higher doses go directly to the tumor area while lower doses are delivered to adjacent areas. A variation of IMBRT called image guided radiation therapy (IGRT) uses real-time images of the patient’s prostate to help deliver more precise doses of radiation.

- Proton beam radiation therapy is similar to 3D-CRT but uses a proton beam instead of the x-ray type photon beam used in standard radiation. Proton beams cause less damage than photon beams to the tissues they pass through on the way to the target. However, the machines used to deliver proton beams are extremely expensive and are not widely available. Not all insurance companies pay for this type of radiation therapy.

Fatigue is a common side effect for several months following radiation therapy. Other complications may include:

Gastrointestinal and Bowel Complications. Short-term effects include nausea and loss of appetite. Diarrhea is a very common side effect and can last for the duration of therapy. It is often treated with Lomotil. It usually goes away eventually, but some patients may have diarrhea flare-ups for years afterward. Newer 3D-CRT techniques may be less likely to cause diarrhea than standard EBRT.

Urinary Problems. Many patients experience a need for frequent urination shortly after radiation therapy, and urgency persists longterm for some patients. Some men experience urinary incontinence (loss of bladder control) but this is less common with radiation than with surgery.

Erectile Dysfunction. Unlike surgery, erectile dysfunction does not usually occur immediately following radiation therapy. However, the risk for this complication increases progressively over a year or more. Drug therapies for erectile dysfunction may help.

Brachytherapy (Internal Radiation)

Brachytherapy is a type of radiation therapy used mainly for men who have early-stage or localized prostate cancer. It can also be used in combination with external beam radiation therapy.

Brachytherapy involves implanting radioactive pellets ("seeds") directly into the prostate. Implants can be permanent or temporary:

- In permanent brachytherapy, the pellets are surgically implanted and sealed in place to continue to deliver low-dose radiation for weeks or months.

- In temporary brachytherapy, the pellets are deposited and held temporarily in place inside of catheters for a treatment session that lasts 5 – 15 minutes. The catheters and pellets are then removed. The patient usually receives about 3 treatments over the course of 2 days. With temporary brachytherapy, a higher dose of radiation can be used.

Side effects for brachytherapy are similar to those for external beam radiation therapy. Side effects specific to brachytherapy include:

Seed Migration. In some cases the seeds can move (migrate). If seeds migrate, they usually end up in the urethra or bladder and are passed out of the body through urination or ejaculation. (Condoms should be worn for first times of intercourse following seed implantation.) Seeds may potentially migrate through the bloodstream to other parts of the body such as the lungs but this happens very rarely and does not appear to cause any long-term problems..

Radiation Exposure. With permanent brachytherapy, the patient can emit small, low-dose amounts of radiation for several weeks. During this time, he patient needs to minimize contact with pregnant women or small children, and will need to wear a condom during sex.

PSA Bounce. It is common for PSA levels to temporarily rise, or "bounce," following seed implantation but this is not a sign of cancer recurrence or cause for concern.

Adjuvant and Salvage Radiation

Radiation may help select patients who still have detectable levels of PSA after surgery (generally 2 ng/mL or less). It may even be useful years after surgery if PSA levels rise.

Depending on timing, radiation after treatment failure is referred to as either:

- Adjuvant radiation is radiation therapy performed within 6 months after radical prostatectomy. One area of controversy is whether to use adjuvant radiation after surgery on patients whose PSA levels are very low or undetectable but who have other test results that indicate the cancer is likely to spread. Patients with adverse findings and low PSA have to weigh the potential complications of radiation therapy against the odds of recurrence without it.

- Salvage radiation is radiation therapy more than 6 months after surgery. Some studies suggest that salvage radiation could be more beneficial than previously thought, even for men with aggressive prostate cancer.

Cryosurgery (Cryoablation)

Cryosurgery is an alternative to standard prostatectomy for men with early-stage, localized prostate cancer who do not want or who are not appropriate candidates for radical prostatectomy. It is also an alternative to radiation therapy.

The goal of cryosurgery is destruction of the entire prostate gland and possibly surrounding tissue. Steel probes are inserted through the skin between the anus and the rectum and guided into the prostate using transrectal ultrasound. Liquid nitrogen is pumped through the probes to freeze all prostate cells, both healthy and cancerous. For success, cryosurgery requires a uniformly frozen area. The dead cells are absorbed and eliminated by the body.

Cryosurgery is typically a 2-hour outpatient procedure, although some patients may need to stay in the hospital overnight. Cryosurgery may also be used as a salvage procedure for patients who have undergone radiation therapy and have had cancer recurrence detected early. It is generally not helpful for men with very large prostate glands.

Nearly all patients experience erectile dysfunction after cryosurgery, and urinary incontinence is also common in men who were first treated with radiation therapy. Other complications of cryosurgery include urinary retention, swelling, and fistula formation. Incontinence and fistulas are more likely to occur when cryosurgery is used as a salvage procedure than when it is used as a primary procedure.

This therapy is still considered experimental by some doctors, and there are no long-term data to compare its effectiveness with standard prostatectomy. For this reason, cryosurgery is generally not considered as a first-line initial treatment.

Hormone Therapy and Chemotherapy

Androgen Deprivation Therapy (Hormone Therapy)

Androgen deprivation therapy (also called androgen suppression therapy or hormone therapy) uses drugs or surgery to suppress or block male hormones, particularly testosterone, which stimulate the growth of prostate cells. Androgen deprivation therapy is not a cure for prostate cancer, but it can help control symptoms and disease progression.

Androgen deprivation therapy is not usually recommended for early-stage prostate cancer. It is mainly used for:

- Advanced (metastatic) cancer that has spread beyond the prostate gland

- Cancer that has failed to respond to surgery or radiation

- Cancer that has recurred

Androgen deprivation therapy may also be used:

- Before radiation or surgery to help shrink tumors

- Along with radiation therapy for cancer that is likely to recur

- Before, during, and after radiation therapy for locally advanced prostate cancer

There is debate about when to start androgen deprivation therapy. In general, doctors recommend delaying hormone therapy until patients with recurrent, progressive, or advanced prostate cancer begin to experience symptoms from their cancer. However, when therapy is postponed, patients should regularly visit their doctors every 3 - 6 months for careful monitoring of their condition.

First-line androgen deprivation therapies include:

- Removal of both testicles (bilateral orchiectomy)

- Injections with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) agonists

- Combining an anti-androgen drug along with orchiectomy or LH-RH agonist drugs is sometimes used as first-line treatment but this approach (“combined androgen blockade”) is controversial and it appears to offer few advantages over standard methods of androgen deprivation.

When prescribing hormone therapy drugs, some doctors recommend periodically stopping and restarting treatment (intermittent therapy). This approach appears to help men avoid erectile dysfunction, hot flashes, and other hormone therapy side effects that impair quality of life. However, it is not yet clear if intermittent therapy works as well as continuous therapy for prostate cancer treatment. Some studies indicate that continuous therapy is more effective or that intermittent therapy should only be used for select types of prostate cancer. Other research suggests that intermittent androgen deprivation is as effective as continuous therapy. More research is needed.

Orchiectomy

Bilateral orchiectomy is the surgical removal of both testicles (surgical castration). It is the single most effective method of reducing androgen hormones but is the effects are permanent. Orchiectomy plus radical prostatectomy may delay progression in patients with cancers that have spread only to the pelvic lymph nodes.

Men who have orchiectomy have reduced sexual function and desire. Patients do not experience a reversal of sex characteristics and the voice does not change. Like all androgen deprivation therapies, orchiectomy increases the risk for osteoporosis.

LH-RH (GnRH) Agonists and Antagonists

The main drugs used for suppressing androgens are called luteinizing hormone-releasing hormones (LH-RH) agonists; they are also known as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists or LH-RH analogs. These drugs block the pituitary gland from producing hormones that stimulate testosterone production. They include leuprolide (Lupron, Eligard, Viadur, generic), goserelin (Zoladex),triptorelin (Trelstar), and histrelin (Vantas). LH-RH agonists are given by injection.

Treatment with LH-RH agonists produces a testosterone surge in the first week, which may actually intensify symptoms. After this phase, testosterone levels drop to near zero. LHRH agonists can also cause PSA levels to rise temporarily.

LH-RH antagonists stop the production of testosterone by blocking LH-RH and do not cause a testosterone surge. The LH-Rh antagonist degarelix (Firmagon) is approved for treatment of advanced prostate cancer. It is given as a monthly injection.

Side Effects. Common side effects include hot flashes, fatigue, testicle shrinkage, and breast enlargement. These drugs may increase blood sugar levels and the risk for developing diabetes. They may also increase risk for heart attack, stroke, and sudden death. (For more detailed information, see “Complications and Side Effects” below.)

Anti-Androgens

Anti-androgens are drugs used to block the effects of testosterone. They are generally used in combination with LH-RH agonists or orchiectomy to completely block androgen hormones. An anti-androgen is usually added when the other hormone treatment stops working. (As mentioned above, the use of anti-androgens as first-line treatment is controversial.)

The anti-androgen drugs used for prostate cancer treatment are flutamide (Eulexin, generic), nilutamide (Nilandron), and bicalutamide (Casodex, generic). They are taken as daily pills. When taken with an LH-RH agonist, hot flashes and breast tenderness is intensified. Nilutamide can cause problems seeing in the dark.

Abiraterone (Zytiga) is an anti-androgen drug that is used for patients with advanced prostate cancer who have already had chemotherapy with docetaxel. It is taken once a day as a pill along with prednisone. Side effects may include joint swelling, fluid swelling in legs and feet, muscle discomfort, hot flashes, high blood pressure, and low levels of potassium in the blood.

Enzalutamide (Xtandi) is another new anti-androgen pill for men with advanced prostate cancer who were previously treated with docetaxel. Enzalutamide is taken as a daily pill. Unlike abiraterone, it does not need to be taken along with prednisone. Its side effects are similar to abiraterone except that enzalutamide may increase the risk for seizures.

Both enzalutamide and abiraterone decrease production of testosterone, but in different ways. These drugs offer important new treatment options for men with advanced prostate cancer. However, they are very expensive. Abiraterone costs more than $60,000 per year and enzalutamide close to $90,000.

Complications and Side Effects of Androgen Deprivation Therapy

Hormonal therapy may significantly impair quality of life, particularly in men who had no symptoms beforehand and whose cancer has not metastasized. Common side effects of androgen suppression may include:

- Hot flashes, which may go away over time

- Osteoporosis, the loss of bone density. Medications such as denosumab (Prolia) and zoledronic acid (Zometa) may be used to help increase bone mass and prevent bone fractures in men receiving hormone therapy.

- Decrease in HDL (“good” cholesterol) levels

- Loss of muscle mass

- Weight gain

- Decreased mental alertness

- Fatigue and depression

- Swelling and tenderness of the breasts (gynecomastia)

- Anemia (low red blood cell count)

- Sexual dysfunction (erectile dysfunction) and loss of sexual drive (low libido)

In addition, there is growing evidence that androgen deprivation drug therapy increases the risks for heart attack, stroke, and diabetes. These drugs increase body weight, which can lead to decreased insulin sensitivity and harmful changes in cholesterol levels. Guidelines recommend that men who receive androgen deprivation therapy should have regular follow-up exams with their primary care doctors within 3 - 6 months after starting therapy. The doctor should monitor the patient’s blood pressure and perform blood sugar (glucose) and cholesterol (lipid tests) at least once a year.

Chemotherapy for Hormone-Resistant Cancer

Prostate cancer that does not respond to hormonal treatment is called hormone-resistant, or hormone-refractory, cancer. Chemotherapy may be used to treat hormone-resistant cancer.

Chemotherapy drugs for prostate cancer include docetaxel (Taxotere), mitoxantrone (Novantrone, generic), estramustine (Emcyt), and various platinum-based drugs, such as carboplatin. These drugs are often combined with other cancer drugs (such as 5-fluorouacil) or corticosteroids (such as prednisone).

Docetaxel-based drug regimens, such as docetaxel in combination with prednisone, are emerging as the main chemotherapy treatment for hormone-refractory prostate cancer. They may help extend survival time by several months. Side effects can be serious and may include gastrointestinal problems (nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea), fatigue, low blood cell counts, and increased risk for blood clots.

Cabazitaxel (Jevtana) is a chemotherapy drug approved for patients whose condition has worsened during or after treatment with docetaxel. It is used in combination with prednisone. Side effects are similar to those of docetaxel.

Abiraterone (Zytiga) and enzalutamide (Xtandi) are new anti-androgen drugs that are approved for patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer who have already had chemotherapy with docetaxel. [See “Antiandrogens” above.]

Other Drug Treatments for Prostate Cancer

Alternatives to Hormone Therapy. If patients do not respond to standard hormonal medications, other drugs may be tried. They include estrogen therapy and ketoconazole (Nizoral, generic), an anti-fungal drug that blocks testosterone production.

Prostate Cancer “Vaccine.” In 2010, the FDA approved a new type of treatment for select men with advanced prostate cancer. Sipuleucel-T (Provenge) is a cancer “vaccine.” Unlike typical vaccines, it does not prevent disease. Instead, it uses the patient’s own immune system to fight the cancer. Each vaccine is individually manufactured by obtaining a patient’s immune cells from his blood. The cells are then exposed to a special type of protein and infused back into the patient.

In clinical trials, Provenge extended survival time by an average of four months. Side effects ranged from mild (chills, fatigue, fever, nausea, joint and muscle aches) to severe (stroke). Provenge is very expensive (about $93,000 a year), but some insurers, including Medicare, are beginning to offer coverage for it, with some restrictions.

Resources

- www.cancer.gov -- National Cancer Institute

- www.cancer.org -- American Cancer Society

- www.asco.org -- American Society of Clinical Oncology

- www.cancer.net -- Cancer.Net

- www.pcf.org -- Prostate Cancer Foundation

- www.urologyhealth.org -- Urology Health

- www.nccn.org -- National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- www.ustoo.org -- Us Too! Prostate Cancer Education and Support

- www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials -- Find clinical trials

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Comparative effectiveness of therapies for clinically localized prostate cancer: executive summary no. 13. AHRQ Pub. No. 08-EHC010-1. February 2008.

Andriole GL, Bostwick DG, Brawley OW, Gomella LG, Marberger M, Montorsi F, et al. Effect of dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 1;362(13):1192-202.

Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL 3rd, Buys SS, Chia D, Church TR, et al. Mortality results from a randomized prostate-cancer screening trial. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 26;360(13):1310-9. Epub 2009 Mar 18.

Antonarakis ES, Eisenberger MA. Expanding treatment options for metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011 May 26;364(21):2055-8.

Babaian RJ, Donnelly B, Bahn D, Baust JG, Dineen M, Ellis D, et al. Best practice statement on cryosurgery for the treatment of localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 2008 Nov;180(5):1993-2004. Epub 2008 Sep 25.

Basch E, Oliver TK, Vickers A, Thompson I, Kantoff P, Parnes H, et al. Screening for prostate cancer with prostate-specific antigen testing: American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion. J Clin Oncol. 2012 Aug 20;30(24):3020-5. Epub 2012 Jul 16.

Chou R, Croswell JM, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Blazina I, Fu R, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Dec 6;155(11):762-71. Epub 2011 Oct 7.

Crook JM, O'Callaghan CJ, Duncan G, Dearnaley DP, Higano CS, Horwitz EM, et al. Intermittent androgen suppression for rising PSA level after radiotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012 Sep 6;367(10):895-903.

D'Amico AV, Chen MH, Renshaw AA, Loffredo M, Kantoff PW. Androgen suppression and radiation vs radiation alone for prostate cancer: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008 Jan 23;299(3):289-95.

de Bono JS, Logothetis CJ, Molina A, Fizazi K, North S, Chu L, et al. Abiraterone and increased survival in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011 May 26;364(21):1995-2005.

Denham JW, Steigler A, Lamb DS, Joseph D, Turner S, Matthews J, et al. Short-term neoadjuvant androgen deprivation and radiotherapy for locally advanced prostate cancer: 10-year data from the TROG 96.01 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011 May;12(5):451-9.

Gaziano JM, Glynn RJ, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of prostate and total cancer in men: the Physicians' Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009 Jan 7;301(1):52-62. Epub 2008 Dec 9.

Holmström B, Johansson M, Bergh A, Stenman UH, Hallmans G, Stattin P. Prostate specific antigen for early detection of prostate cancer: longitudinal study. BMJ. 2009 Sep 24;339:b3537. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3537.

Hu JC, Gu X, Lipsitz SR, Barry MJ, D'Amico AV, Weinberg AC, et al. Comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive vs open radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 2009 Oct 14;302(14):1557-64.

Jang TL, Bekelman JE, Liu Y, Bach PB, Basch EM, Elkin EB, et al. Physician visits prior to treatment for clinically localized prostate cancer. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Mar 8;170(5):440-50.

Klein EA, Thompson IM Jr, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011 Oct 12;306(14):1549-56.

Kramer BS, Hagerty KL, Justman S, Somerfield MR, Albertsen PC, Blot WJ, et al. Use of 5-alpha-reductase inhibitors for prostate cancer chemoprevention: American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Urological Association 2008 Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 20;27(9):1502-16. Epub 2009 Feb 24.

Levine GN, D'Amico AV, Berger P, Clark PE, Eckel RH, Keating NL, et al. Androgen-deprivation therapy in prostate cancer and cardiovascular risk: a science advisory from the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society, and American Urological Association: endorsed by the American Society for Radiation Oncology. Circulation. 2010 Feb 16;121(6):833-40. Epub 2010 Feb 1.

Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, Brandeis JM, Lee SP, Withers HR, et al. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007 Jun 1;109(11):2239-47.

Loblaw DA, Virgo KS, Nam R, Somerfield MR, Ben-Josef E, Mendelson DS, et al. Initial hormonal management of androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate cancer: 2006 update of an American Society of Clinical Oncology practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Apr 20;25(12):1596-605. Epub 2007 Apr 2.

Lu-Yao GL, Albertsen PC, Moore DF, Shih W, Lin Y, DiPaola RS, et al. Survival following primary androgen deprivation therapy among men with localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2008 Jul 9;300(2):173-81.

Moyer VA; on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Prostate Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Jul 17;157(2):120-134.

Sanda MG, Dunn RL, Michalski J, Sandler HM, Northouse L, Hembroff L, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. N Engl J Med. 2008 Mar 20;358(12):1250-61.

Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TL, Ciatto S, Nelen V, et al. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009 Mar 26;360(13):1320-8. Epub 2009 Mar 18.

Shelley M, Wilt TJ, Coles B, Mason MD. Cryotherapy for localised prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jul 18;(3):CD005010.

Theoret MR, Ning YM, Zhang JJ, Justice R, Keegan P, Pazdur R. The risks and benefits of 5a-reductase inhibitors for prostate-cancer prevention. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jun 15. [Epub ahead of print]

Thompson I, Thrasher JB, Aus G, Burnett AL, Canby-Hagino ED, et al. Guideline for the management of clinically localized prostate cancer: 2007 update. J Urol. 2007 Jun;177(6):2106-31.

Walsh PC, DeWeese TL, Eisenberger MA. Clinical practice. Localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007 Dec 27;357(26):2696-705.

Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Rutks I, Shamliyan TA, Taylor BC, Kane RL. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of treatments for clinically localized prostate cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Mar 18;148(6):435-48. Epub 2008 Feb 4.

Wolf AM, Wender RC, Etzioni RB, Thompson IM, D'Amico AV, Volk RJ, et al. American Cancer Society guideline for the early detection of prostate cancer: update 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010 Mar-Apr;60(2):70-98. Epub 2010 Mar 3.

|

Review Date:

9/19/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |