Hodgkin's disease

Highlights

Hodgkin’s Disease

Hodgkin’s disease is a lymphoma, a cancer of the lymphatic system. Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma are the two types of lymphomas. Hodgkin’s disease is distinguished by the presence of large abnormal cells, called Reed-Sternberg cells. The disease is less common than non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Hodgkin’s disease is classified into two main types:

- Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma, which includes nodular sclerosis and mixed cellularity, the two most common subtypes

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease, which affects about 5% of patients

Prognosis

Hodgkin’s disease is considered one of the most curable forms of cancer, especially if it is diagnosed and treated early. Five-year survival rates for patients diagnosed with stage I or stage II Hodgkin’s disease are 90 - 95%. Many patients with late-stage Hodgkin’s disease also have good odds for survival.

Risk Factors

Hodgkin's disease occurs most often in people ages 15 - 40 (especially in their 20s), and in people over age 55. About 10 - 15% of Hodgkin’s disease cases are diagnosed in children and teenagers. It is slightly more common in males than in females.

Certain types of viral infections may increase the risk of Hodgkin’s disease. Infectious mononucleosis, which is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, is associated with increased risk as is infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Treatment

Chemotherapy and radiation are the main treatments for Hodgkin’s disease. Patients who have relapsed may be treated with autologous stem cell transplantation, a procedure which uses the patient's own blood cells.

Preventing Infection after Cancer Treatment

Both chemotherapy and stem cell transplants increase the risk for serious infections. Patients must take precautions to avoid exposure to germs. Ways to prevent infection include:

- Practice good hygiene, including regular handwashing and dental care (brushing, flossing).

- Avoid crowds, especially during cold and flu season.

- Eat only well-cooked foods (no raw fruits or vegetables).

- Boil tap water before drinking it.

- Do not keep fresh flowers or plants in your house as they may carry mold.

Drug Approval

In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved brentuximab (Adcetris), the first new treatment for Hodgkin’s since 1977. Brentuximab is indicated for patients with Hodgkin’s disease who have either failed to respond to at least two chemotherapy regimens and are not candidates for a transplant, or who have undergone a transplant but failed to respond to it.

Brentuximab is a biologic drug that targets the protein CD30. It is given by intravenous infusion. The drug may cause many side effects. Serious side effects may include increased risk for the brain disorder progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

Introduction

Hodgkin's disease is a type of lymphoma. Lymphomas are cancers of the lymphatic system. They are generally subdivided into two groups: Hodgkin's disease (HD) and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL). NHL is discussed in another report. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #84: Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas.] Hodgkin’s disease is also called Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Hodgkin’s disease is marked by the presence of abnormal large cells called Reed-Sternberg cells. Reed-Sternberg cells are derived from B cell lymphocytes (white blood cells). Reed-Sternberg cells are specific to Hodgkin’s disease. They are not found in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

HD usually starts in B cell lymphocytes located in lymph nodes in the neck area, although any lymph node may be the site of initial disease.

Types of Hodgkin's Disease

There are two major types of Hodgkin’s disease: Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease.

Classical Hodgkin's Lymphoma. Classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma accounts for about 95% of Hodgkin’s disease cases. It has four major subtypes:

- Nodular Sclerosis. Nodular sclerosis is the most common subtype, representing about 60 - 80% of HD cases. Younger patients are more likely to have this type. The nodes first affected are often those located in the center of the chest (the mediastinum) or the neck.

- Mixed Cellularity. Mixed cellularity is the next most common HD form, occurring in about 15 - 30% of patients, mostly in older adults. Mixed cellularity refers to the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells and other cell types.

- Lymphocyte Rich. The lymphocyte-rich subtype accounts for about 5% of all HD cases. It tends to affect men more than women.

- Lymphocyte Depleted. The lymphocyte-depleted subtype is the least common type of HD, occurring in only about 1% of cases. It is usually seen in older people and patients infected with HIV. It is also more common in less developed countries. The cancer tends to be diagnosed when it is widespread, affecting the spleen, bone marrow, and liver as well as abdominal lymph nodes.

Nodular Lymphocyte-Predominant Hodgkin's Disease. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin's disease occurs in about 5% of patients. It is distinct from classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The cells look like and are referred to as “popcorn” cells, which are variants of Reed-Sternberg cells. This type of HD typically affects younger patients and usually originates in the neck lymph nodes. It is sometimes confused with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). In fact, there is a 3 - 5% risk that nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin’s disease can transform into diffuse large B-cell NHL.

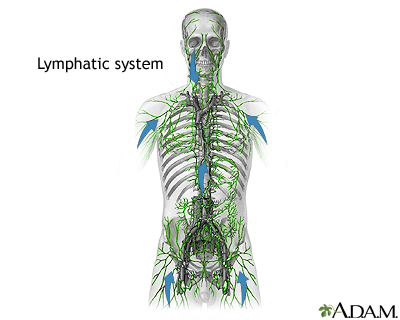

The Lymphatic System

Lymphomas are tumors of the lymphatic system. This system is a network of organs, ducts, and nodes. The lymphatic system transports a watery clear fluid called lymph throughout the body. The lymphatic system contains lymphocytes, which are important cells involved in defending the body against infections.

Lymphocytes. Lymphocytes, which are white blood cells, are a primary component of the immune system.

- Lymphocytes develop either in the bone marrow (called B cells or bone marrow-derived cells) or in the thymus gland (called T cells or thymus gland-derived cells).

- Both leukemia and lymphomas (Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas) are cancers of lymphocytes. The difference is that leukemia starts in the bone marrow while lymphomas originate in lymph nodes and then spread to the bone marrow or other organs.

Lymphatic vessels. Lymphatic vessels begin as tiny tubes. These tubes collect and carry fluids that leak from body tissues, lymphocytes, proteins, and other substances collected from the body's tissues. The tubes lead to larger lymphatic ducts and branches, which drain into two ducts in the neck, where the fluid re-enters the bloodstream.

Lymph Nodes. Along the way, the fluid passes through lymph nodes, which are oval structures made up of lymph vessels, connective tissue, and white blood cells.

- The normal size of a lymph node varies from that of a pinhead to a bean. Most nodes are clustered throughout the body. Node clusters are found in the neck, lower arm, armpit, and groin, as well throughout the inside of the body.

- In a lymph node, lymphocytes are first exposed to foreign substances, such as bacteria. This exposure prompts the lymphocytes to produce antibodies, which target and attack these foreign proteins (antigens). More lymphocytes may also be made in the lymph node and added to the contents of the lymph fluid.

- Lymphocytes from elsewhere in the body may also be filtered out of the lymph fluid into the lymph node.

Other Structures in the Lymphatic System. The tonsils and adenoids are secondary lymphatic organs. They are composed of masses of lymph tissue that also play a role in the lymphatic system. The spleen is another important organ that processes lymphocytes from incoming blood.

Spread of Cancer. Unfortunately, tumor cells may enter the lymph fluid and travel to the lymph nodes. Hodgkin's disease usually progresses in an orderly way from one lymph node region to the next. This process may be slow, particularly in younger people, or very rapid. The disease typically spreads downward from the initial site.

- If it spreads below the diaphragm, it usually reaches the spleen first; the disease may then spread to the liver and bone marrow.

- If the disease starts in the nodes in the middle of the chest, it may spread outward toward the chest wall and areas around the heart and lungs.

Risk Factors

Hodgkin’s disease is less common than non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It accounts for about 11.5% of all lymphomas. According to the American Cancer Society, about 9,000 new cases of Hodgkin's disease (HD) are diagnosed in the United States each year. The exact causes of Hodgkin’s disease are unknown. Research indicates that the malignant process leading to Hodgkin's disease may be triggered by a combination of environmental and genetic factors along with a susceptible immune system.

Age and Gender

Hodgkin's disease occurs most often in people ages 15 - 40 (especially in their 20s), and in people over age 55. About 10 - 15% of Hodgkin’s disease cases are diagnosed in children and teenagers.

Hodgkin's disease is slightly more common among males than females. Women who get Hodgkin's disease appear to have a slightly lower risk for relapse after treatment than men.

Viral Infection

Infectious mononucleosis (“mono”), which is caused by the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), is linked with increased risk for Hodgkin’s disease. However, only 1 in 1,000 patients with mononucleosis develops Hodgkin's disease. The Epstein-Barr virus is present in 90% of all people and, in the great majority of these cases, the virus causes a mild case of mononucleosis or no illness at all. Only a very small percentage of people who have had mononucleosis go on to develop HD. Other factors must be present to trigger the malignancy.

People infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which weakens the immune system, are also at increased risk of developing Hodgkin’s disease.

Family

Hodgkin's disease runs in families in about 5% of cases. Siblings of patients have a three times higher risk than the general population.

Symptoms

Symptoms of Hodgkin’s disease may include:

- Swollen (but painless) lymph nodes in the neck, armpits, or groin

- Pain in lymph nodes after drinking alcohol

- Itching throughout body (pruritis)

- Persistent fatigue

- Coughing, difficulty breathing, or chest pain may indicate that swollen lymph nodes in the chest are pressing on the windpipe

- Unexplained weight loss of more than 10% in previous 6 months

- Persistent fever

- Drenching night sweats

The last three symptoms (weight loss, fever, and night sweats) are classified as “B symptoms.” B symptoms may be used in staging Hodgkin’s disease and can indicate that more aggressive treatment will be required.

Sometimes patients with Hodgkin’s disease do not experience any symptoms, or symptoms may not appear until the cancer is very advanced. Enlarged lymph nodes can also be caused by many noncancerous conditions, such as infections.

Diagnosis

The doctor will take a medical history and perform a physical examination. If these simple procedures point to Hodgkin's disease, a number of additional tests may be needed to either rule out other diseases or confirm HD and determine the extent of the cancer.

Physical Examination

The doctor will examine not only the affected lymph nodes but also the surrounding tissues and other lymph node areas for signs of infection, skin injuries, or tumors. The consistency of the node is evaluated. For example, a stony, hard node is often a sign of cancer, usually one that has metastasized (spread to another part of the body). A firm, rubbery node may indicate lymphoma (including Hodgkin's). Soft tender nodes suggest infection or inflammatory conditions.

Blood Tests

Blood tests are performed to measure white and red blood cells, blood protein levels, the uric acid level, blood proteins, and the liver's function.

Imaging Techniques

Chest X-Ray. A chest x-ray may show lymph nodes in the chest, where Hodgkin's disease usually starts. It a useful step for detecting enlarged lymph nodes.

Computed Tomography. Computed tomography (CT) scans are much more accurate than x-rays. They can detect abnormalities in the chest and neck area, as well as revealing the extent of the cancer and whether it has spread. CT scans are used to evaluate symptoms and help diagnose lymphomas, help with staging of the disease, and monitor response to treatment. A CT scan is also often used to detect lymphomas in the abdominal and pelvic areas, the brain, and chest area.

Positron Emission Tomography (PET). PET scans combined with CT scans can help doctors clarify the location of the cancer. PET scans can also provide information on whether or not an enlarged lymph node is benign or cancerous and can be used for staging lymphomas. PET scans may also help doctors determine how well a patient has responded to treatment, if any residual cancer exists, and if a patient has achieved remission.

Biopsy

A biopsy of the suspicious lymph node is the definitive way to diagnose Hodgkin's disease. The lymph node sample will be examined by a pathologist for the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells or other abnormal features.

The type of biopsy performed depends in part on the location and accessibility of the lymph node. The doctor may surgically remove the entire lymph node (excisional biopsy) or a small part of it (incisional biopsy). In some cases, the doctor may use fine needle aspiration to withdraw a small amount of tissue from the lymph node. Biopsies of bone marrow may also be performed in patients with existing Hodgkin's disease if the doctor suspects that it may have spread to the marrow.

Prognosis

Hodgkin’s disease is considered one of the most curable forms of cancer, especially if it is diagnosed and treated early. Unlike other cancers, Hodgkin's disease is even potentially curable in late stages Five-year survival rates for patients diagnosed with stage I or stage II Hodgkin’s disease are 90 - 95%. With advances in treatment, recent studies indicate that even patients with advanced Hodgkin’s disease have 5-year survival rates of 90%, although it is not yet certain if their disease will eventually return. Patients who survive 15 years after treatment are more likely to later die from other causes than from Hodgkin’s disease.

Survival rates are poorest for patients who:

- Relapse within a year of treatment

- Do not respond to the first-line therapy and have signs of disease progression

Factors that Influence Prognosis

The International Prognostic Factors Project on Advanced Hodgkin's Disease uses seven factors to help determine which patients with advanced Hodgkin's disease have a more serious prognosis and could benefit from more aggressive chemotherapy. These factors are also used to predict success in patients with relapsed or persistent HD who are undergoing stem cell transplantation.

The more of these factors that are present, the worse the outlook and the more likely the patient needs to be treated aggressively:

- Being male

- Age of 45 years or older

- Stage IV disease

- Low blood albumin level (less than 4g/dL; albumin is a type of protein.)

- Low hemoglobin level (less than 10.5g/dL; hemoglobin is the oxygen-carrying component of red blood cells)

- High white blood cell count (more than 15,000)

- Low lymphocyte count (less than 600)

Long-Term Effects of Treatments

The good news about Hodgkin's disease is that treatment can cure the disease. The bad news is that survivors face a higher than average risk for long-term complications of these treatments, some very serious.

Many patients experience chronic fatigue that can sometimes last for years. The most serious complications are secondary cancers and heart disease, which may develop over the 20 - 30 years following treatments. Secondary cancers include non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, leukemia, melanoma, stomach and lung cancers, and breast and uterine cancers. Heart disease complications include coronary artery disease, stroke, heart valve problems, and cardiomyopathy (weakening of the heart muscle). Thyroid disorders are also a potential complication. Combinations of radiation and chemotherapies pose the highest risk of these problems.

Studies of adult survivors of various childhood cancers have found that, 30 years after treatment, patients with cured Hodgkin’s disease are especially likely to have developed other serious health problems. Female survivors have a significantly greater risk than male survivors. In particular, women who received chest radiation are at very high risk for developing breast cancer.

Patients with Hodgkin’s disease should get a written record of the treatments they received as children, and the potential risks of these treatments. These records can help the doctors who later oversee their care monitor for potential health problems. Survivors of Hodgkin’s disease should receive regular screening tests for cancer and heart disease. They may need to get these tests at a younger age than most patients. In particular, patients who were treated with chest radiation should get blood tests every 5 years to measure their cholesterol levels. Female patients who received chest radiation should get early and frequent mammograms.

Treatment

Treatment options depend on:

- Type of Hodgkin’s disease

- Tumor stage, size, and location

- Patient’s age and overall health status

- Presence or absence of “B symptoms” (weight loss, persistent fever, night sweats)

Certain factors may determine whether more intensive treatment is required. For example, the presence of B symptoms and “bulky” (large mass) tumors usually indicates a more aggressive treatment approach.

Chemotherapy, radiation, or both (chemoradiation) are the main treatments for Hodgkin’s disease. Stem cell transplantation may be recommended for patients whose cancer has recurred.

Staging

Hodgkin’s disease is staged (I through IV) depending on how far the cancer has spread. Staging is the primary method for determining both treatment options and prognosis.

Stage I. Disease is limited to a single node region (I) or has involved one neighboring area or a single nearby organ.

Stage II. Disease is limited to two or more lymph nodes on the same side of (above or below) the diaphragm or extends locally from the lymph node into a nearby organ.

Stage III. Disease is in lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm or has spread to nearby organs, the spleen, or both.

Stage IV. Disease has become widespread involving organs outside the lymph system, such as liver, lung, or bone marrow.

Treatment Options by Stage

Early Stages (I or II). For disease in stages I or II, the following treatments may be used:

- Treatment in Adults. Doctors usually recommend chemotherapy and sometimes radiation therapy as the first-line treatments for adults with Hoddkin's. Treatment provides excellent remission rates, although it may produce serious long-term complications in some patients. Select patients in early stages may also be candidates for radiation limited only to areas above the diaphragm (called the mantle field).

- Treatment in Children. Chemotherapy and low-dose radiation is the standard treatment for most children and adolescents who have not reached full growth. Specific chemotherapy combinations have been developed to reduce the risks for infertility, leukemia, and toxic effects on the heart and lungs.

Later Stages. For stage III disease, chemotherapy, often with radiation, is a standard treatment. For stage IV disease, chemotherapy alone is generally recommended. Newer types of chemotherapy regimens are achieving survival rates that reach 90%.

Relapse. Relapse after treatment occurs in 20 - 35% of patients. Treatments for relapse include chemotherapy, radiation, and bone marrow or blood stem cell transplantation. Many patients respond favorably to such treatments, although another relapse is still possible.

Preparing for Side Effects before Treatment

Preventing Infection. Both the disease and some of the treatments suppress the immune system, increasing the risk for infections. Widespread, life-threatening infection is a particular danger if the spleen has been removed and both radiation and chemotherapy are administered. Patients should be vaccinated against three bacteria: pneumococcus, meningococcus, and Haemophilus influenza before receiving treatment.

Preserving Fertility. Patients who may wish to have children in the future should discuss the possibility with their doctors options for fertility-preserving treatments. Men with Hodgkin's disease may want to consider sperm freezing and assisted reproductive techniques. Women should ask their doctors about taking hormonal drugs called GnRH analogs before and during chemotherapy.

[For more information on fertility preservation treatments, see In-Depth Report #67: Male infertility and In-Depth Report #22: Female infertility.]

Monitoring after Treatment

Relapse of Hodgkin’s disease is not uncommon, even after treatment for early stages. It can occur a decade or more after treatment. Relapse is more likely to occur in early-stage disease, probably because limited radiation normally used in such cases does not destroy all malignancies. Patients who had large tumors in the chest are also at higher risk for recurrence.

Patients need periodic examinations and imaging tests for years after treatment, both to check for signs of relapse as well as to monitor the long-term effects of treatments. Conditions to watch for include inflammation in the lungs and thyroid disease from radiation in the chest, and heart disease and cancers from combined treatments, chemotherapy and blood stem cell transplantation.

Treatment of Pregnant Women

Because Hodgkin's disease often occurs in young adults, treatment for pregnant women is of particular concern. Therapy must be effective enough to protect the mother without hurting the fetus. Chemotherapy is rarely used early in the term, because it poses a risk for birth defects. Treatment choice must be individualized, taking into consideration the mother's wishes, the severity and pace of the disease, and the remaining length of the pregnancy. The treatment plan may need to be changed as the pregnancy progresses. If the disease develops in the second half of the pregnancy, it may be possible to postpone chemotherapy or radiation therapy until after an early induced delivery.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy, which shrinks tumors, has been used to treat Hodgkin's disease for more than 50 years . High-dose radiation is generally reserved for adults. Radiation treatments are very toxic for children and appear to add little benefit. In young patients, radiation is mostly used if there are large areas of disease in the chest; otherwise, chemotherapy, which may be combined with low-dose radiation, is the best option and produces excellent survival rates.

Radiation Treatment Approaches

The two main types of radiation therapy used for Hodgkin's disease are extended field radiation and involved field radiation.

Extended field radiation targets the diseased lymph nodes and surrounding healthy lymph nodes. Extended-field radiation is rarely given in combination with chemotherapy. Specific subtypes of extended field radiation are used depending on the location of the disease:

- If HD is above the diaphragm, “extended field radiation” is delivered to the neck, chest, and under arms (called the mantle field). Radiation is sometimes expanded to include lymph nodes in the upper abdomen.

- If cancer is below the diaphragm, an "inverted Y" field is sometimes used, in which radiation is directed at lymph nodes in the upper abdomen, spleen, and pelvis.

- Inverted Y-field radiation therapy combined with mantle-field radiation is called total nodal radiation.

Involved field radiation targets only lymph node regions that are known to have cancer, not the adjacent, uninvolved lymph node regions. Involved-field radiation is usually given after several rounds of chemotherapy.

In general, recent research suggests that extended-field radiation adds little survival advantage and carries a greater risk of serious side effects. Involved-field radiation is now becoming the preferred method. In recent studies, a lower-dose involved-field radiation, combined with chemotherapy, helped achieve good outcomes for patients with early-stage Hodgkin’s disease who had a favorable prognosis. More research is needed before standard practice guidelines can be implemented.

Complications of Radiation

Infections. Infections may be a particular problem with radiation combined with chemotherapy. All patients should be vaccinated against the bacteria that often cause pneumonia and meningitis, and against the influenza virus.

Infertility. Radiation therapy to the pelvic area can adversely affect later fertility in women and men. Such negative effects may be worse in women; sperm usually recover within 5 years.

Heart Disease and Stroke. Radiation is associated with a future risk of heart disease, which includes atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) and diseases of the heart valves. Lower doses pose less risk. Recent research suggests that adults who survived childhood Hodgkin’s disease have a four times higher risk of having a stroke than healthy patients. Children with Hodgkin’s disease who receive radiation to the head or neck also have an increased risk for later having a stroke at a younger than average age.

Fatigue. Fatigue is significant and chronic in many survivors. It is more highly associated with intensive chemotherapy, but it also may be a late response to radiation treatment.

Secondary Cancers. Second cancers (such as breast, stomach, lung, melanoma) may develop later in areas within or at the edge of the radiation area. Thyroid, respiratory tract, and digestive tract secondary cancers may affect patients who were treated as children. Lung cancer in survivors is highly associated with smoking after treatment, and no survivor should smoke. The risk for breast cancer increases significantly in women who receive chest radiation. The risk can persist for 25 years or more after radiotherapy, and lifetime monitoring (including frequent mammograms) is essential.

Thyroid Disorders. Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) occurs in a number of patients treated with radiation treatments. There is also a 5% chance for hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid).

Impaired Growth in Children. Children and adolescents are at special risk for impaired bone growth.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. The drugs are called cytotoxic (“toxic to cells”) medications. Chemotherapy is referred to as body-wide, or systemic, therapy because the drugs affect cells throughout the body.

Chemotherapy drugs may be taken by mouth as pills or given by injection or infusion. Treatment may be administered at a medical center, doctor's office, or even a patient's home. Some patients receiving chemotherapy may need to remain in the hospital for several days so the effects of the drug can be monitored.

Patients typically receive 4 - 8 cycles of chemotherapy, depending on the stage. A cycle is usually 28 days and consists of several doses of drug administration followed by a period of rest.

Specific Drugs and Drug Combinations Used in Hodgkin's Disease

The standard chemotherapy regimens for Hodgkin’s disease are ABVD and Stanford V.

ABVD consists of a 4-drug combination:

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

- Bleomycin

- Vinblastine

- Dacarbazine

Stanford V consists of a 7-drug combination:

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

- Mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard)

- Vincristine

- Vinblastine

- Bleomycin

- Etoposide

- Prednisone

BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) is a chemotherapy regimen reserved for high-risk patients. This regimen is proving to be extremely effective, particularly in advanced stages, with studies reporting remission rates of over 95% in patients with advanced Hodgkin's. However, this regimen also increases the risk for developing secondary cancers such as leukemia. Patients who are treated with BEACOPP should receive long-term follow-up care to monitor for side effects from this therapy.

Brentuximab (Adcetris) is a new drug that is used by itself. In 2011, it was approved for patients with Hodgkin’s disease who have either:

- Failed to respond to at least two prior multidrug chemotherapy regimens and who are not candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation

- Undergone a transplant but have not been helped by it

Brentuximab works by targeting CD-30, a protein found on Hodgkin’s cancer cells. The drug is given by intravenous infusion. Brentuximab is a very new drug and not all of its side effects or complications are fully known. The most common side effects are neutropenia, peripheral sensory neuropathy, fatigue, nausea, and anemia. At least two cases of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a rare but serious brain disorder, have occurred with this drug.

Side Effects and Complications

Side effects and complications of any chemotherapeutic regimen are common, are more severe with higher doses, and increase over the course of treatment. Some studies suggest that toxicities can be reduced by administering the drugs for shorter duration without loss of cancer-killing effects.

Common Side Effects. Common side effects of chemotherapy include:

- Nausea and vomiting -- drugs known as serotonin antagonists, including ondansetron (Zofran) or granisteron (Kyril), can relieve these side effects in nearly all patients given moderate drugs and most patients who take more powerful drugs.

- Diarrhea

- Hair loss

- Mouth sores

- Weight loss

- Depression

Serious Side Effects. Serious side effects can also occur and may vary depending on the specific drugs used. They include:

- Neutropenia is a severe drop in the number of white blood cells produced in the bone marrow. Neutropenia increases the chance for infection and is a potentially life-threatening condition. Drugs called granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) are used to help boost white blood cell count. These drugs, which include filgrastim (Neupogen) and pegfilgrastim (Neulasta) can help lessen the risk for neutropenia occurrence and, if neutropenia does occur, to reduce its length and severity.

- Anemia is a reduced number of red blood cells. Erythropoietin stimulates red blood cell (hemoglobin) production and can help reduce or prevent this side effect. It is available as epoetin alfa (Epogen, Procrit) and darbepoetin alfa (AranespIn patients with cancer, these drugs should be used to only treat anemia associated with chemotherapy and to increase hemoglobin levels to no more than 12 g/dL. Treatment should stop as soon as chemotherapy is complete. These drugs may not be safe or appropriate for all patients.

- Peripheral sensory neuropathy is damage to the peripheral nerves that carry signals to and from the spinal cord to the rest of the body. Symptoms can include tingling, burning, and loss of sensation in the legs and arms. Peripheral neuropathy can also cause problems to muscles, the digestive system, and body organs including the heart.

- Infection. Patients must take precautions against infections (see "Infection Prevention" in Transplant section).

- Liver and kidney damage

- Abnormal blood clotting (thrombocytopenia)

- Allergic reaction

Long-Term Complications.

- Fatigue and general aches and pains are called somatic symptoms. Fatigue is especially common after chemotherapy and can sometimes last for several years.

- Many women stop menstruating after chemotherapy. The risk for infertility is highest for women with advanced-stage Hodgkin’s disease who are treated after age 30. Studies indicate that the risk for infertility is higher with BEACOPP than with ABVD. Researchers are studying whether taking oral contraceptives during chemotherapy can reduce the risk.

- Bone thinning (osteoporosis) may be related to steroid treatments such as prednisone.

- Heart failure may occur with the use of anthracycline drugs (such as doxorubicin).

- Bleomycin (Blenoxane) is particularly toxic to the lungs. Vinblastine may also pose a risk when used in combination with radiation therapy.

In general, these serious late side effects are dependent on the cumulative drug dose and rate of administration.

Combinations of Chemotherapy and Radiation (Combined Modality)

Chemotherapy (usually ABVD) plus involved-field radiation, referred to as combined modality, is a common treatment approach for patients with more advanced-stage disease and for those who have early-stage bulky (large mass) disease. Chemotherapy with low-dose radiation is also used in children with excellent results, even for late-stage cancer.

Transplantation

Patients with relapsed or progressive HD are often treated with high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem cell transplantation procedures. (Transplantation does not appear to offer an advantage compared to standard chemotherapy as initial treatment for patients with high-risk advanced HD.)

This treatment involves removal and replacement of stem cells, which are produced in the bone marrow. This allows the patient to receive high-dose chemotherapy without destroying these important cells. Stem cells are the early forms for all blood cells in the body (including red, white, and immune cells). Cancer treatments harm growing cells as well as cancer cells, and so the healthy stem cells must be replaced by transplanting them.

For Hodgkin’s disease, the most common type of transplant is an autologous procedure, using the patient’s own cells. An allogeneic transplant, using cells from a donor, is more risky for patients with Hodgkin’s disease and is generally used only when an autologous transplant has failed. (This section provides information pertinent to autologous procedures. Detailed information on allogeneic transplants, including such complications as graft-versus-host-disease, can be found in In-Depth Report #84: Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma.)

Transplantation Procedure

Stem cells must first be collected in one of the following ways:

- Directly from blood (peripheral blood stem cell transplantation)

- From bone marrow (bone marrow transplantation)

Stem cells are collected several weeks before the procedure. They are frozen and stored while the patient undergoes high-dose chemotherapy. Some patients receive high-dose whole body radiation therapy along with chemotherapy.

After the patient completes the pre-transplant therapy, the frozen cells are thawed and then infused into the patient. Within a few weeks, these cells start to generate new white blood cells and then new red blood cells.

Infection

The risk for infection is greatest during the first 6 weeks following the transplant. During this period, a patient usually remains in isolation and receives antibiotics and intravenous nutrition. It takes 6 - 12 months post-transplant for a patient’s immune system to fully recover.

Many patients develop severe herpes zoster virus infections (shingles) or have a recurrence of herpes simplex virus infections (cold sores and genital herpes). Pneumonia, cytomegalovirus, aspergillus (a type of fungus), and Pneumocystis jirovecii (a fungus) are among the most serious life-threatening infections.

It is very important that patients take precautions to avoid infections. Guidelines for infection prevention include:

- Discuss with your doctor what vaccinations you need and when you should get them.

- Avoid crowds, especially during cold and flu season.

- Be diligent about handwashing, and make sure that visitors wash their hands. Alcohol-based handrubs are best.

- Avoid eating raw fruits and vegetables -- food should be well cooked. Do not eat foods purchased at salad bars or buffets. In the first few months after the transplant, be sure to eat protein-rich foods to help restore muscle mass and repair cell damage caused by chemotherapy and radiation.

- Boil tap water before drinking it.

- Dental hygiene is very important, including daily brushing and flossing. Schedule regular visits with your dentist.

- Do not sleep with pets. Avoid contact with pets’ excrement.

- Avoid fresh flowers and plants as they may carry mold. Do not garden.

- Swimming may increase exposure to infection. If you swim, do not submerge your face in water. Do not use hot tubs.

- Report to your doctor any symptoms of fever, chills, cough, difficulty breathing, rash or changes in skin, and severe diarrhea or vomiting. Fever is one of the first signs of infection.

- Report to your ophthalmologist any signs of eye discharge or changes in vision. Patients who undergo radiation or who are on long-term steroid therapy have an increased risk for cataracts.

Other Side Effects and Complications

Early side effects of transplantation are similar to chemotherapy and include nausea, vomiting, fatigue, mouth sores, and loss of appetite. Bleeding because of reduced platelets is a high risk during the first four weeks and may require transfusions. Later side effects include fertility problems (if the ovaries are affected), thyroid gland problems (which can affect metabolism), lung damage (which can cause breathing problems), other organ damage, and bone damage.

In younger patients, there is a small long-term risk for leukemia after transplantation. Chemotherapy itself increases the risk of secondary cancers. Recent studies suggest that transplantation after chemotherapy does not add any additional risks.

Resources

- www.cancer.gov -- National Cancer Institute

- www.cancer.org -- American Cancer Society

- www.lymphoma.org -- Lymphoma Research Foundation

- www.leukemia.org -- Leukemia and Lymphoma Society

- www.asco.org -- American Society of Clinical Oncology

- www.cancer.net -- Cancer.Net

- www.lymphomainfo.net -- Lymphoma Information Network

- www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials -- Find clinical trials

References

Armitage JO. Early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 12;363(7):653-62.

Brenner H, Gondos A, Pulte D. Ongoing improvement in long-term survival of patients with Hodgkin disease at all ages and recent catch-up of older patients. Blood. 2008;111 (6): 2977-83.

Castellino SM, Geiger AM, Mertens AC, Leisenring WM, Tooze JA, Goodman P, et al. Morbidity and mortality in long-term survivors of Hodgkin lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Blood. 2011 Feb 10;117(6):1806-16. Epub 2010 Oct 29.

Eichenauer DA, Engert A, Dreyling M; ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Hodgkin's lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2011 Sep;22 Suppl 6:vi55-8.

Engert A, Plütschow A, Eich HT, Lohri A, Dörken B, Borchmann P, et al. Reduced treatment intensity in patients with early-stage Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2010 Aug 12;363(7):640-52.

Fermé C, Eghbali H, Meerwaldt JH, et al. Chemotherapy plus involved-field radiation in early-stage Hodgkin's disease. N Engl J Med. 2007 Nov 8;357(19):1916-27.

Horning SJ. Hodgkin’s lymphoma. In: Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Niederhuber JE, Kastan MB, McKena WG, eds. Clinical Oncology. 4th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2008:chap 111.

Juweid ME, Stroobants S, Hoekstra OS, et al. Use of positron emission tomography for response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the Imaging Subcommittee of International Harmonization Project in Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Feb 10;25(5):571-8. Epub 2007 Jan 22.

Morris B, Partap S, Yeom K, Gibbs IC, Fisher PG, King AA. Cerebrovascular disease in childhood cancer survivors: A Children's Oncology Group Report. Neurology. 2009 Dec 1;73(22):1906-13. Epub 2009 Oct 7.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Hodgkin Lymphoma. V.1.2012.

Oeffinger KC, Ford JS, Moskowitz CS, Diller LR, Hudson MM, Chou JF, et al. Breast cancer surveillance practices among women previously treated with chest radiation for a childhood cancer. JAMA. 2009 Jan 28;301(4):404-14.

Viviani S, Zinzani PL, Rambaldi A, Brusamolino E, Levis A, Bonfante V, et al. ABVD versus BEACOPP for Hodgkin's lymphoma when high-dose salvage is planned. N Engl J Med. 2011 Jul 21;365(3):203-12.

|

Review Date:

2/24/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |