Ovarian cancer

Highlights

Ovarian Cancer

Ovarian cancer is the ninth most common cancer in women, and the fifth leading cause of female cancer death. Detection of ovarian cancer while it is in its early stages significantly improves prognosis. Unfortunately, most cases of ovarian cancer are discovered when the cancer is already advanced.

Screening

Unlike Pap tests for cervical cancer, there is currently no effective screening method for ovarian cancer. Imaging tests such as transvaginal ultrasound and blood tests such as CA-125 have not proven to be useful screening tools. Studies indicate that screening with these tests does not reduce ovarian cancer death and may cause women to undergo unnecessary medical treatment due to their high rate of “false positives.”

The United States Preventive Services Task Force and other medical associations do not recommend routine screening for ovarian cancer for most women. However, these tests can help doctors track the results of treatments for ovarian cancer.

Symptoms

Ovarian cancer grows quickly and can progress from early to advanced stages within a year. Paying attention to symptoms can help improve a woman's chances of being diagnosed and treated promptly. If you have the following symptoms on a daily basis for more than a few weeks, you should see your doctor (preferably a gynecologist):

- Bloating

- Pelvic or abdominal pain

- Difficulty eating or feeling full quickly

Risk Factors

The main risk factors of ovarian cancer are:

- Older age

- Family history of ovarian, breast, or hereditary colorectal cancer

- BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutations

- Obesity

- Hormone replacement therapy use for 5 or more years

- Not having had children

Protective Factors

Factors that may help reduce the risk of ovarian cancer include:

- Birth control pills

- Childbirth and breastfeeding

- Tubal ligation (tying fallopian tubes) or hysterectomy (removal of uterus) after childbearing

- Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy surgery (removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes) may be recommended for women at high risk for ovarian cancer, particularly those who have BRCA1 and BRCA2 genetic mutations

Treatment

Ovarian cancer is usually treated by surgery followed by chemotherapy. Surgery involves removal of the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, and the omentum (a layer of fatty tissue in the abdomen).

Patients with ovarian cancer should seek care from a qualified gynecologic oncologist (a surgical specialist in female reproductive cancers) and a qualified medical oncologist with special expertise in the chemotherapy of gynecologic cancer.

Introduction

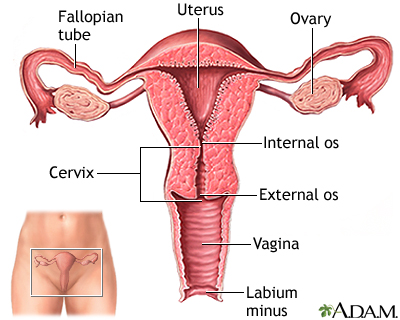

The ovaries are two small, almond-shaped organs located on either side of the uterus. They are key components of a woman's reproductive system:

- Ovaries store 200,000 - 400,000 follicles, tiny sacs that are present from birth that nurture immature eggs (ova).

- During each normal (usually monthly) reproductive cycle, a follicle in one ovary bursts and releases a mature or "ripened" egg. The egg travels down the fallopian tube into the uterus, where it either is fertilized by a man's sperm or, if unfertilized, breaks down and is shed with menstrual bleeding.

- Ovaries produce the important reproductive hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Ovarian Cancers

Ovarian cancers are potentially life-threatening malignancies that develop in one or both ovaries. Malignant ovarian tumors generally fall into three primary classes:

- Epithelial tumors

- Germ cell tumors

- Stromal tumors

Epithelial Tumors. Epithelial tumors account for up to 90% of all ovarian cancers and are the primary focus of this report. These cancers develop in a layer of cube-shaped cells known as the germinal epithelium, which surrounds the outside of the ovaries.

Germ Cell Tumors. Germ cell tumors, which account for about 3% of all ovarian cancers, are found in the egg-maturation cells of the ovary. They occur most often in teenagers and young women. Although they progress rapidly, they are very responsive to treatments. About 90% of patients with germ cell malignancies can be cured, often preserving fertility.

Stromal Tumors. Stromal tumors, which account for about 6% of all ovarian cancers, develop from connective tissue cells that hold the ovary together and that produce the female hormones, estrogen and progesterone. Stromal tumors do not usually spread, in which case the prognosis is good. If they spread, however, they can be more difficult to treat than the other types of ovarian tumors.

Ovarian Cancer Progression

Ovarian cancer progresses almost silently, usually with vague symptoms. By the time serious symptoms do appear, the ovarian tumor may have grown large enough to shed cancer cells throughout the abdomen. At such an advanced stage, the cancer is more difficult to cure.

Ovarian cancer cells that have spread outside the ovaries are referred to as metastatic ovarian cancers. Ovarian tumors tend to spread to the following locations:

- Diaphragm

- Intestine

- Omentum (a layer of fatty tissue in the abdomen)

Cancer cells can also spread to other organs through lymph channels and the bloodstream.

Other Ovarian Growths

Not all ovarian growths are malignant. Benign ovarian cysts are common and are entirely different from ovarian cancer.

Ovarian cysts typically develop in one of two ways:

- Follicular Cysts. During normal ovulation, follicles (the little sacs in the ovary) expel eggs. If the egg is not expelled, fluids and other substances can build up inside the follicle, forming a follicular cyst.

- Corpus Luteum Cysts. Benign cysts may form when an egg has been released, but the emptied follicle (now called the corpus luteum) does not break down normally, instead filling with blood from nearby blood vessels.

Both follicular cysts and corpus luteum cysts are normal parts of the menstrual cycle and nearly always resolve within one or two cycles without treatment.

Risk Factors and Prevention

Ovarian cancer is the ninth most common cancer in women, and the fifth leading cause of female cancer death. Each year in the United States, about 22,000 women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer. About 15,500 American women die each year from the disease.

Certain factors increase the risk for ovarian cancer, while other factors reduce risk. Many of the preventive factors are related to the number of times a woman ovulates during her lifetime, which is indicated by the number of menstrual periods she has. Fewer menstrual periods and ovulations appear to be associated with reduced risk for ovarian cancer.

Factors That Increase the Risk for Ovarian Cancer

The main risk factors for ovarian cancer are:

- Age

- Family history of ovarian, breast, or colorectal cancer

- Genetic mutations

- Obesity

- Hormone replacement therapy use

- Menstrual and reproductive history

Age. Ovarian cancer risk increases with age. About two-thirds of women are diagnosed with ovarian cancer at age 55 or older. The average age for the onset of ovarian cancer is about age 63, although ovarian cancer can develop in women of all ages.

Family History. A family history of breast or ovarian cancer is one of the strongest risk factors for ovarian cancer. Women are also at high risk for ovarian cancer if they have a family history of a hereditary form of colorectal cancer.

In general, women are considered at high risk for ovarian cancer if they have:

- A first-degree relative (mother, sister, or daughter) with ovarian cancer at any age. The risk increases with the number of affected first-degree relatives.

- A first-degree relative (or two second-degree relatives on the same side) with early onset breast cancer (occurring before age 50)

- A family member with both breast and ovarian cancer

- A family history of male breast cancer

- A family history of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

- Ashkenazi (Eastern European) Jewish ancestry

When a woman describes her family history to her doctor, she should include the history of cancer in women on both the mother's and the father's side. Both are significant.

Genetic Mutations. The main genetic mutations associated with increased ovarian cancer risk are:

- BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. Inherited mutations in the genes called BRCA1 and BRCA2 increase the risk for ovarian and breast cancers. While these mutations are more common among women of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, they are not restricted to this population and can occur in women of any ethnicity, including women of Asian and African descent. Women with a BRCA1 mutation have about a 40% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer. Women with a BRCA2 mutation have about a 10 - 20% lifetime risk for ovarian cancer. (By contrast, the lifetime ovarian cancer risk for women in the general public is about 1.4%.)

- HNPCC. Women who have genetic mutations associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) have about a 12% lifetime risk of developing ovarian cancer

Obesity. Many studies have found an association between obesity and increased risk for ovarian cancer.

Hormone Replacement Therapy (HRT). Long-term use (more than 5 years) of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may increase the risk of developing and dying from ovarian cancer. The risk seems to be particularly significant for women who take estrogen-only HRT. The risk is less clear for combination estrogen-progestin HRT. For women who take HRT, those who have a uterus (have not had a hysterectomy) are given combination HRT because progestin helps protect against the development of uterine cancer.

Menstrual and Reproductive History. Women are at increased risk for ovarian cancer if they began menstruating at an early age (before age 12), have not had any children, had their first child after age 30, or experienced early menopause (before age 50).

Endometriosis. Endometriosis may increase the risk for certain types of ovarian cancer. However, most women with endometriosis do not develop ovarian cancer. Endometriosis is a condition in which the cells that line the uterus grow in other areas of the body, such as the ovaries.

Risk Factors with Less Conclusive Evidence. Dietary fats have been studied as a possible risk factor for ovarian cancer. While some research reports an association between a high intake in animal fats and a greater risk, other studies have not found that dietary fat intake increases the risk for ovarian cancer.

Some older studies indicated that use of the fertility drug clomiphene (Clomid) could increase the risk for ovarian cancer. However, infertility itself is a risk factor for ovarian cancer, so it is not certain whether fertility drugs play an additional role in affecting risk. More recent studies suggest that fertility drugs do not increase ovarian cancer risk.

There is inconclusive evidence as to whether environmental factors increase the risk for ovarian cancer. Possible carcinogens studied include radiation exposure, talcum powder, and asbestos.

Factors That Appear to Reduce the Risk for Ovarian Cancer

In general, factors or behaviors that limit stimulation of the ovaries or inhibit ovulation seem protective. These preventive factors include:

- Oral contraceptive use

- Pregnancy and childbirth

- Tubal ligation and hysterectomy

Oral Contraceptives. Birth control pills definitely reduce the risk of ovarian cancer. Studies suggest that routine use of birth control pills reduces a woman's risk of ovarian cancer by about 50% when compared to women who have never taken oral contraceptives. The longer a woman takes oral contraceptives the greater the protection and the longer protection lasts after stopping oral contraceptives. However, birth control pills are not safe or appropriate for all women. [For more information, see In-Depth Report #91: Birth control options for women.]

Pregnancy and Childbirth. The more times a woman gives birth, the less likely she is to develop ovarian cancer. Breast-feeding for a year or more after giving birth may also decrease ovarian cancer risk.

Tubal Ligation and Hysterectomy. Tubal ligation, a method of sterilization that ties off the fallopian tubes, has been associated with a decreased risk for ovarian cancer when it is performed after a woman has completed childbearing. Similarly, hysterectomy, the surgical removal of the uterus, is also associated with decreased risk. However, these procedures should not be performed solely for ovarian cancer risk reduction.

Preventive Factors with Less Conclusive Evidence. Some studies, but not all, have suggested that tea consumption is associated with reduced risk of ovarian cancer.

Preventive Strategies for High-Risk Women

Women with a strong family history of ovarian cancer may wish to discuss these preventive strategies with their doctors.

Genetic Counseling and Screening for BRCA Genes. The latest guidelines from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommend BRCA testing for women at high risk for ovarian cancer. The USPSTF does not recommend routine genetic counseling or testing for BRCA genes in low-risk women (no family history of BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutations).

Screening with Ultrasound or Blood Tests. Screening high risk women is not recommended:

- Transvaginal ultrasound is not helpful for identifying early-stage ovarian cancer in high-risk women. In addition, ultrasound does not provide enough specific information to reliably determine which abnormal masses are cancerous or noncancerous.

- The CA-125 blood test is not approved for screening in the general population.

Evidence indicates that these screening tests do not help prevent ovarian cancer death. In addition, these tests produce a high level of “false positives,” meaning that women may be incorrectly subjected to unnecessary invasive tests for ovarian cancer.

Removal of Ovaries (Oophorectomy). Surgical removal of the ovaries, called oophorectomy, significantly reduces the risk for ovarian cancer. When it is used to specifically prevent ovarian cancer in high-risk women, the procedure is called a prophylactic oophorectomy. Prophylactic oophorectomy is approximately 95% protective against ovarian cancer and is recommended for women at high risk for ovarian cancer. These women generally have the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutation, or have two or more first-degree relatives who have had ovarian cancer.

Bilateral oophorectomy is the removal of both ovaries. Bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the removal of both fallopian tubes plus both ovaries. Several recent studies indicate that salpingo-oophorectomy is very effective in reducing risk for ovarian cancer in women who carry the BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation.

Even after oophorectomy, women in high-risk groups for ovarian cancer still have a risk for the development of cancer in the peritoneum (the thin membrane that lines the inside of the abdomen).

Premenopausal women should be aware that oophorectomy causes immediate menopause, which poses a risk for several health problems, including osteoporosis and heart disease. Estrogen replacement, given for a period of time, can help offset these problems but may cause problems of its own. Women who have a bilateral oophorectomy and do not receive hormone replacement therapy may experience more severe hot flashes than women who naturally enter menopause.

Symptoms

Ovarian cancer used to be considered a "silent killer." Symptoms were thought to appear only when the cancer was in an advanced stage. Now, doctors believe that even early-stage ovarian cancer can produce symptoms.

See your doctor if you have the following symptoms on a daily basis for more than a few weeks:

- Bloating

- Pelvic or abdominal pain

- Difficulty eating or feeling full quickly

Ovarian cancer grows quickly and can progress from early to advanced stages within a year. Paying attention to symptoms can help improve a woman's chances of being diagnosed and treated promptly. Detecting cancer while it is still in its earliest stages may help improve prognosis.

Be aware that these symptoms are very common in women who do not have cancer and are not specific for ovarian cancer. While prompt follow-up with your doctor is important when one or more of these are present, there are many other explanations for these symptoms besides ovarian cancer.

Other symptoms are also sometimes associated with ovarian cancer. These symptoms include fatigue, indigestion, back pain, pain during intercourse, constipation, and menstrual irregularities.

Based on the symptoms and physical examination, the doctor may order pelvic imaging tests or blood tests. If these tests reveal possible signs of cancer, patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist who specializes in female reproductive system cancers.

Diagnosis

Up to 95% of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer will survive longer than 5 years if the cancer is treated before it has spread beyond the ovaries. Although doctors are working hard to develop ways to diagnose early ovarian cancer, there are currently no effective screening tests for early detection. Therefore, only about 25% of ovarian cancer cases are diagnosed at such early stages. It is possible to perform genetic screening in high-risk women, but this raises some complex issues.

Annual Gynecologic Checkup

Every woman should have a regular annual examination with her doctor that includes a pelvic exam.

A pelvicexam is performed in two ways. The doctor inserts two fingers into the vagina while feeling the abdomen with the other hand. The doctor also performs a bimanual rectovaginal exam, which involves the insertion of one finger into the vagina and another into the rectum.

Both exams enable the doctor to evaluate the size and shape of the ovaries. Enlarged ovaries and abdominal swelling can be signs of ovarian cancer. A mass felt during a pelvic exam often requires further evaluation by ultrasound and sometimes requires surgery to make a definitive diagnosis.

Ruling out Benign Conditions

Many women are treated each year in the United States because of ovarian growths or lesions. Many more women find out about some ovarian abnormality during their annual gynecological exam. The vast majority of conditions are noncancerous. They include:

- Benign functional ovarian cysts

- Abscesses and infection

- Fibroids

- Endometriosis

- Polycystic ovaries

- Ectopic pregnancies

- Meig syndrome (a benign ovarian growth associated with fluid buildup in the abdomen and around the lungs)

- Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome following fertility treatments.

Once a growth is detected, the additional tests described below may help the doctor evaluate the risk for it being cancerous. If ovarian cancer has been diagnosed, these tests are also used to monitor how the cancer is progressing.

Transvaginal Ultrasound and Other Imaging Tests

Ultrasound. Ultrasound is a noninvasive diagnostic tool that can evaluate tumors and masses discovered during the rectovaginal exam:

- Typically, a probe that emits sound waves (ultrasound) is placed in the vagina. The sound waves bounce off tissues, organs, and masses in the pelvic cavity. These echoes are collected and converted into a picture of the area called a sonogram. Healthy tissue, fluid-filled cysts, and solid tumors produce different sound waves.

- The ultrasound probe may also be placed on abdominal walls above the ovaries (transabdominal ultrasound), but it does not provide as clear a picture of the ovaries. This technique may be needed to evaluate larger masses or cancer that has spread into the abdomen.

Other Imaging Techniques. Other imaging techniques are less common for the diagnosis or evaluation of suspected ovarian cancer but may help determine if cancer has spread to other parts of the body:

- Computed tomography (CT). Computed tomography records x-ray absorption rates of tissue and bone. These data are converted into clear images on a screen. CT scans help determine if cancer has spread to the lymph nodes, abdominal organs, abdominal fluid, and the liver.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI creates multiple cross-sectional images of the pelvis and abdominal organs, which are assembled into three-dimensional images. An MRI is not usually used to diagnose ovarian cancer, but may help determine if cancer has spread to the brain or spinal cord.

- Chest x-rays. Find cancer that has spread to the lungs.

CA-125 and Other Blood Tests

CA-125 Blood Test. CA-125 is a protein that is secreted by ovarian cancer cells and is elevated in over 80% of patients with ovarian cancer. Oncologists will usually only obtain a blood test for this protein if ovarian cancer is strongly suspected or has been diagnosed. In general, a CA-125 level is considered to be normal if it is less than 35 U/mL (microns per milliliter). The test may also be useful for evaluating tumor growth and predicting survival in patients with recurrent cancer who have been treated with topotecan or paclitaxel-carboplatin chemotherapy regimens.

The test is not useful for diagnosis or early screening, however. In about half of women with very early ovarian cancer, CA-125 levels are not elevated above the normal standard. Furthermore, an elevated level can be caused by a number of other conditions including:

- Endometriosis

- Fibroids

- Noncancerous ovarian cysts

- Pregnancy

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Liver diseases

- Heart failure

- Other tumors, such as breast, colon, lung, and pancreatic cancers

- Age and menstrual status can also affect the levels of CA-125

OVA1 Blood Test. The OVA1 blood test helps predict whether ovarian cancer is more likely to be present in a pelvic mass. The test measures the level of CA-125 and four other proteins. The test can help doctors decide what type of surgery should be performed. The OVA1 test is used in addition to, not in place of, other diagnostic and clinical procedures. It is not used to screen for or provide a definite diagnosis of ovarian cancer, but can help doctors to determine that a malignancy is more likely to be present.

Exploratory Surgery

An exploratory surgical procedure is required to confirm a diagnosis of ovarian cancer. It is also necessary to properly stage a patient, since the imaging tests may miss small implants of ovarian tumor within the pelvis and the abdominal cavity. Surgery may be laparotomy or a less-invasive laparoscopy. A gynecologic oncologist usually performs these procedures.

Laparotomy is an open-surgery procedure that requires general anesthesia. The surgeon makes an incision from the pubic bone to the navel to explore the abdominal cavity. Laparoscopy does not require general anesthesia and the oncologist uses only small incisions to insert a lighted instrument to examine the organs and evaluate the spread of the tumor. With both procedures, tissue samples (biopsies) can be removed for further testing.

Prognosis

About 75% of women survive ovarian cancer at least 1 year after diagnosis. Nearly half are alive 5 years after diagnosis. This is called the 5-year survival rate.

Survival rates vary depending on different factors, including age and the stage at which it is detected. In general, women younger than age 65 have better survival rates than older women.

Unfortunately, most patients with ovarian cancer are not diagnosed until the disease is advanced. This usually means the cancer has spread to the upper abdomen. In order to establish a prognosis and determine treatment, the doctor needs to know the cell type, stage, and grade of the disease.

Prognosis by Cell Type

When examined under the microscope, there are a number of different cell types of ovarian cancer. Mucinous and clear cell tumors tend to be more difficult to treat.

Prognosis by Stage

Cancers are staged (I through IV) according to whether they are still localized (remaining in the ovary) or have spread beyond the original site.

The survival rate varies according to the cancer stage:

- Five-year survival rates are over 90% if the cancer is still confined to the ovary at diagnosis. However, only 19% of ovarian cancers are found at this stage.

- If the cancer has spread to nearby regions in the pelvis, the 5-year survival rate is about 70%.

- If the cancer has spread to sites outside the pelvis, the 5-year survival rate is about 30%.

Prognosis by Grade

Tumors are graded according to how well or poorly organized they are (their differentiation). Ovarian tumors are graded on a scale of 1, 2, or 3. Grade 1 tends to closely resemble normal tissue and has a better prognosis than grade 3, which indicates very abnormal, poorly defined tissue.

Treatment

In general, the course of treatment is determined by the stage of the cancer. Stages range from I to IV based on the cancer's specific characteristics, such as whether it has spread beyond the ovaries. Surgery is the main treatment for ovarian cancer. Following surgery, women with higher-stage tumors may receive chemotherapy. Women can also consider enrolling in clinical trials that are investigating new types of treatments.

About 10 - 15% of epithelial ovarian tumors are referred to as "borderline" because their appearance and behavior under the microscope is between benign and malignant. These tumors are also called "carcinomas of low malignant potential" because they rarely metastasize or cause death. Borderline ovarian tumors are most often seen in younger women with epithelial ovarian cancer. Surgery is usually recommended to remove these tumors. Chemotherapy may also be used to treat borderline tumors that appear to have more aggressive features (such as recurring after surgery).

Stages

Stage I. In stage I, the cancer has not spread. It is confined to one ovary (stage IA) or both ovaries (stage IB). In stages IA and IB, the ovarian capsules are intact, and there are no tumors on the surface. Stage IC can affect one or both ovaries, but the tumors are on the surface, or the capsule is ruptured, or there is evidence of tumor cells in abdominal fluid (ascites). The overall 5-year survival rate for stage IA or IB can be as high as 90%, depending on the type of tumors and whether cells are well or poorly differentiated. Stage IC has a poorer outlook than the earlier stages. It is very important that women receive an accurate staging assessment, including a pathologic review conducted by a gynecologic pathologist.

Stage II. In stage II, the cancer has spread to other areas in the pelvis. It may have advanced to the uterus or fallopian tubes (stage IIA), or other areas within the pelvis (stage IIB), but is still limited to the pelvic area. Stage IIC indicates capsular involvement, rupture, or positive washings (that is, they contain malignant cells).

Stage III. In stage III, one or both of the following are present: (1) The cancer has spread beyond the pelvis to the omentum (a layer of fatty tissue in the abdomen) and other areas within the abdomen, such as the surface of the liver or intestine. (2) The cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage IV. Stage IV is the most advanced cancer stage. The cancer may have spread to the inside of the liver or spleen. There may be distant spreading of the cancer, such as ovarian cancer cells in the fluid around the lungs.

Treatment Options for Stage I and Stage II Ovarian Cancer

Treatment options for stage I and stage II ovarian epithelial cancer may include:

- Surgery: Removal of the uterus (total hysterectomy), removal of both ovaries and fallopian tubes (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy); partial removal of the omentum (omentectomy); and surgical staging of the lymph nodes and other tissues in the pelvis and abdomen. (Carefully selected premenopausal women in Stage I with the lowest-grade tumors in one ovary may sometimes be treated only with the removal of the diseased ovary and tube in order to preserve fertility.)

- Chemotherapy: Patients with stage IA or B disease, grade 1 (or sometimes grade 2), usually do not need further therapy after surgery. However, higher risk patients (stage IC, stage I/grade 3) are usually treated with platinum-based chemotherapy to reduce their risk of subsequent relapse.

- Clinical trials with radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or new treatments

Treatment Options for Stage III and Stage IV Ovarian Cancer

Treatment options for stage III and stage IV ovarian epithelial cancer may include:

- Surgery: Removal of the tumor (debulking), total abdominal hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oopherectomy, and omentectomy

- Chemotherapy: Combination chemotherapy with a platinum-based drug and a taxane drug delivered intraperitoneally (through the abdominal cavity)

- Clinical trials of biologic drugs (targeted therapy) following combination chemotherapy

Treatment Options for Recurrent Ovarian Cancer

If ovarian cancer returns or persists after treatment, chemotherapy is the mainstay of treatment, although it is not generally curative in the setting of relapsed disease. Clinical trial options include additional surgical debulking, and biologic drug therapy combined with chemotherapy.

Surgery

Surgery for ovarian cancer uses laparotomy, a major abdominal operation. It is the primary diagnostic tool for ovarian cancer and also plays a role in treatment. Complete surgical intervention includes the following:

- Surgical staging (examining all tissues and organs in the pelvic cavity for accurate assessment of the disease stage).

- Debulking (removal of as much of the cancerous tissue as possible). This is an important component of ovarian cancer management and should be performed by a surgeon trained in cancer surgery techniques.

Patients with ovarian cancer should see a qualified gynecologic oncologist (a surgical specialist in female reproductive cancers) and a qualified medical oncologist with special expertise in the chemotherapeutic management of gynecologic cancer. Studies indicate that it is best for patients, especially those with advanced-stage ovarian cancer, to receive care at medical centers that specialize in cancer treatment and surgery.

Surgical Staging

Surgical staging includes biopsies of the following:

- The undersurface of the diaphragm

- The omentum (a layer of fatty tissue in the abdomen)

- Sometimes lymph nodes along the abdominal aorta

An abdominal wash is performed by injecting a salt solution into the abdominal cavity to facilitate microscopic detection of cancerous cells not visible to the naked eye. The surgeon then evaluates the pelvis and abdomen and removes suspected cancer tissue. The entire affected ovary is usually removed (oophorectomy) during surgical staging if the surgeon believes it might be cancerous. The tissue is sent to a laboratory for an immediate evaluation called a frozen section diagnosis. The doctor will also examine the bowel and bladder for cancer invasion.

Preservation Surgery in Premenopausal Women with Early Cancer

If the tumor is in an early stage on one ovary and a woman wants to retain her ability to have children, the surgeon may be able to remove only the affected ovary and perform surgical staging. Chemotherapy follows in select patients. Studies indicate that in carefully selected young patients, many can expect normal fertility afterward. However, most women with ovarian cancer are not candidates for this procedure.

Total Hysterectomy and Bilateral Salpingo-Oophorectomy and Debulking

The goal of surgery is to remove as much of the tumor as possible for improving symptoms and increasing the effectiveness of chemotherapy. The surgery itself is typically performed as follows:

- In premenopausal women in later stages of ovarian cancer, and in all postmenopausal women, the surgeon usually removes the uterus (a hysterectomy) and both ovaries and fallopian tubes (a bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy).

- In addition, the surgeon usually removes the omentum (omentectomy), any growths on the diaphragm and intestine, and possibly certain lymph nodes (lymphadenectomy).

If surgical staging reveals that the cancer has invaded the bowel, a portion of the intestine may have to be removed as well.

Treating Menopausal Symptoms and Premature Menopause. The ovaries produce estrogen. Removing the ovaries results in menopause. After removal of the ovaries, premenopausal women usually have hot flashes, a symptom of menopause. Symptoms come on abruptly and may be more intense than those of natural menopause. Symptoms include hot flashes, vaginal dryness and irritation, and insomnia. A significant number of women gain weight.

The most important complications that occur in women who have had their ovaries removed are due to estrogen loss, which places women at risk for osteoporosis (loss of bone density) and a possible increase in risks for heart disease. In the past, women were typically prescribed estrogen-only hormone replacement therapy (HRT) after surgery if their ovaries were removed. There have been concerns however about health risks, including the risk for breast cancer and stroke, which have now limited its use.

The decision to use estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) depends in part on a woman's age as well as other medical factors. For younger women (in their 20s, 30s, or 40s), the benefits of ERT for bone and heart health may outweigh the risks. For women closer to the age of menopause, risks may outweigh benefits. Women who have had an oopherectomy should discuss with their doctors whether ERT is appropriate for them.

[For more information on hysterectomy, see In-Depth Report #73: Uterine fibroids and hysterectomy. For information on hormone replacement therapy, see In-Depth Report #40: Menopause.]

Surgery for Bowel Obstruction

Bowel obstruction is common in ovarian cancer. Surgery can be very helpful for select patients with this problem.

Chemotherapy

Following surgery, patients (other than those with early-stage, low-grade disease) usually have chemotherapy. Unlike surgery and radiation, which treat the cancerous tumor and the area surrounding it, drug therapy destroys rapidly dividing cells throughout the body, so it is a systemic therapy.

Ovarian cancers are very sensitive to chemotherapy and often respond well initially. Unfortunately, in most cases, ovarian cancer recurs. With treatment advances, however, more than half of women now survive 5 years or longer. Doctors are now approaching this disease as a chronic and potentially long-term illness that requires the following:

- Identifying the disease recurrence as soon as possible

- Administering treatments that are as effective as possible without causing suffering

- Partnering with the patient in determining her own best course

Drugs Used in Chemotherapy

Standard Chemotherapy. The standard initial chemotherapy uses a combination of:

- A platinum-based drug such as carboplatin (Paraplatin, generic) or cisplatin (Platinol, generic). Carboplatin is preferred over cisplatin in the combination. Carboplatin works as well as cisplatin but is less toxic and can be administered in a more convenient, outpatient regimen.

- A taxane such as paclitaxel (Taxol, generic) or docetaxel (Taxotere, generic). Currently, paclitaxel is the drug most often used as initial therapy in combination with a platinum drug.

Chemotherapy for Relapsed or Refractory Cancer. Unfortunately, even in patients who respond, the disease eventually becomes resistant to the first-line drugs, and the cancer returns. Some ovarian tumors are resistant to platinum drugs.

Once cancer recurs or continues to progress, the patient may be treated with more cycles of carboplatin and a taxane drug, or a different type of chemotherapy drug may be used in combination treatment.

Recurrent ovarian cancer may be treated with gemcitabine (Gemzar, generic), a drug used in combination with carboplatin for women with advanced ovarian cancer that has relapsed at least 6 months after initial therapy. Other drugs used for recurrent ovarian cancer include doxorubicin (Adriamycin, Doxil, generic), etoposide (Vepesid, generic), and vinorelbine (Navelbine, generic).

Hormonal therapy is also an option for patients who cannot tolerate or who have not been helped by chemotherapy. Hormonal therapy drugs include tamoxifen (Nolvadex, generic), and aromatase inhibitors such as letrozole (Femara, generic), anastrozole (Arimidex, generic), and exemestane (Aromasin, generic).

Administration of Chemotherapy

In general, the typical initial chemotherapy regimen is:

- Paclitaxel and carboplatin are administered in an outpatient clinic within several weeks of the surgery.

- Each treatment takes about 4 - 5 hours to complete.

- It is repeated every 3 weeks for a total of six times. (Each 3-week interval is known as a cycle of chemotherapy.)

Chemotherapy is either administered intravenously (by vein) or intraperitoneally (through the abdominal cavity). Recent research has indicated that patients with stage III ovarian cancer who receive intraperitoneal chemotherapy have a significant survival advantage compared with patients who receive standard intravenous chemotherapy. However, intraperitoneal chemotherapy can cause more severe side effects, including abdominal pain and bowel damage. Some patients cannot tolerate intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy requires careful catheter insertion and maintenance, and doctors need to be well trained to perform this procedure.

Side Effects of Chemotherapy

Side effects occur with all chemotherapy drugs. They are more severe with higher doses and increase over the course of treatment. Some may be long-lasting.

Common side effects may include:

- Nausea and vomiting. Drugs known as serotonin antagonists, especially ondansetron (Zofran, generic), can relieve these side effects in nearly all patients given moderate drugs and most patients who take more powerful drugs.

- Diarrhea

- Temporary hair loss

- Weight loss

- Fatigue

- Depression

Serious short- and long-term complications can also occur and may vary depending on the specific drugs used. These complications may include:

- Anemia (low red blood cell count)

- Increased chance for infection from severe reduction in white blood cells (neutropenia)

- Abnormal bleeding (thrombocytopenia)

- Problems with concentration, motor function, and memory

Follow-Up Recommendations

After surgery and chemotherapy, patients should have:

- A physical exam (including pelvic exam) every 2 - 4 months for the first 2 years, followed by every 6 months for 3 years, and then annually.

- A CA-125 blood test at each office visit if the level was initially elevated. Falling CA-125 levels indicate effective treatment while persistently elevated levels indicate resistance to the chemotherapy.

- Your doctor may also order a computed tomography (CT) scan of your chest, abdominal, and pelvic areas and a chest x-ray.

- If your family history suggests a genetic component, genetic counseling may be recommended.

Investigational Drugs

Any patient with ovarian cancer is a candidate for clinical trials. In addition to testing high-dose or combinations of chemotherapy, biologic drugs that target specific proteins are being investigated. These drugs are primarily being studied for treatment of advanced or recurrent ovarian cancer, in combination with standard chemotherapy drugs.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy is not typically used in ovarian cancer. This is because radiation would need to be given to the entire abdomen and pelvis, increasing its toxicity. Radiation is sometimes useful to treat isolated areas of tumor that are causing pain and are no longer responsive to chemotherapy, and to kill cancer cells that still remain after other treatments.

Resources

- www.cancer.gov -- National Cancer Institute

- www.cancer.org -- American Cancer Society

- www.cancer.net -- Cancer.Net

- www.ovarian.org -- National Ovarian Cancer Coalition

- www.ovariancancer.org -- Ovarian Cancer National Alliance

- www.sgo.org -- Society of Gynecologic Oncologists

- www.foundationforwomenscancer.org -- Foundation for Women's Cancer

- www.ovariancancer.com -- The Gilda Radner Familial Ovarian Cancer Registry

- www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials -- Find clinical trials

References

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Management of adnexal masses. Obstet Gynecol. 2007; 110(1): 201-14.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on GynecologicPractice. Committee Opinion No. 477: the role of the obstetrician-gynecologist in the early detection of epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Mar;117(3):742-6.

Berek JS, Chalas E, Edelson M, Moore DH, Burke WM, Cliby WA, et al. Prophylactic and risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy: recommendations based on risk of ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Sep;116(3):733-43.

Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, Johnson CC, Lamerato L, Isaacs C, et al. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2011 Jun 8;305(22):2295-303..

Chan JK, Tian C, Monk BJ, Herzog T, Kapp DS, Bell J, et al. Prognostic factors for high-risk early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2008; 112(10): 2202-10.

Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer, Beral V, Doll R, Hermon C, Peto R and Reeves G. Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls. Lancet. 2008; 371(9609): 303-14.

Daly MB, Axilbund JE, Buys S, Crawford B, Farrell CD, Friedman S, et al. Genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2010 May;8(5):562-94.

Domchek SM, Friebel TM, Singer CF, Evans DG, Lynch HT, Isaacs C, et al. Association of risk-reducing surgery in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carriers with cancer risk and mortality. JAMA. 2010 Sep 1;304(9):967-75..

Elit L, Oliver TK, Covens A, Kwon J, Fung MF, Hirte HW, et al. Intraperitoneal chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of women with stage III epithelial ovarian cancer: a systematic review with metaanalyses. Cancer. 2007; 109(4): 692-702.

Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, Urban N, Gough S, Schurman KM, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15;109(2):221-7.

Goff BA, Matthews BJ, Larson EH, Andrilla CH, Wynn M, Lishner DM, et al. Predictors of comprehensive surgical treatment in patients with ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2007 May 15;109(10):2031-42.

Jensen A, Sharif H, Frederiksen K, Kjaer SK. Use of fertility drugs and risk of ovarian cancer: Danish Population Based Cohort Study. BMJ. 2009 Feb 5;338:b249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b249.

Morch LS, Lokkegaard E, Andreasen AH, Kruger-Kjaer, Lidegaard O. Hormone therapy and ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2009 Jul 15;302(3):298-305.

Pearce CL, Templeman C, Rossing MA, Lee A, Near AM, Webb PM, et al. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case-control studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012 Apr;13(4):385-94. Epub 2012 Feb 22.

Prentice RL, Thomson CA, Caan B, Hubbell FA, Anderson GL, Beresford SA, et al. Low-fat dietary pattern and cancer incidence in the Women's Health Initiative Dietary Modification Randomized Controlled Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007; 99(20): 1534-43.

Rivera CM, Grossardt BR, Rhodes DJ, Brown RD Jr, Roger VL, Melton LJ 3rd, Rocca WA. Increased cardiovascular mortality after early bilateral oophorectomy. Menopause. 2009 Jan-Feb;16(1):15-23.

Tangjitgamol S, Manusirivithaya S, Laopaiboon M, Lumbiganon P. Interval debulking surgery for advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Apr 15;(2):CD006014

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Sep 6;143(5):355-61.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Ovarian Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012 Sep 11. [Epub ahead of print]

Winter-Roach BA, Kitchener HC, Dickinson HO. Adjuvant (post-surgery) chemotherapy for early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009 Jul 8;(3):CD004706.

|

Review Date:

12/20/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |